Archival research

Archival research is a type of research which involves seeking out and extracting evidence from archival records. These records may be held either in collecting institutions,[1] such as libraries and museums, or in the custody of the organization (whether a government body, business, family, or other agency) that originally generated or accumulated them, or in that of a successor body (transferring, or in-house archives).[2] Archival research can be contrasted with (1) secondary research (undertaken in a library or online), which involves identifying and consulting secondary sources relating to the topic of enquiry; and (2) with other types of primary research and empirical investigation such as fieldwork and experiment.

History of archives organizations[]

The oldest archives have been in existence for hundreds of years. For instance, the Vatican Secret Archives was started in the 17th century AD and contains state papers, papal account books, and papal correspondence dating back to the 8th century. Most archives that are still in existence do not claim collections that date back quite as far as the Vatican Archive. The Archives Nationales in France was founded in 1790 during the French Revolution and has holdings that date back to AD 625, and other European archives have a similar provenance. Archives in the modern world, while of more recent date, may also hold material going back several centuries, for example, the United States National Archives and Records Administration was established originally in 1934.[3] The NARA contains records and collections dating back to the founding of the United States in the 18th century. Among the collections of the NARA are the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States, and an original copy of the Magna Carta. The British National Archives (TNA) traces its history to the creation of the Public Record Office in 1838, while other state and national bodies were also formed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Universities are another venue for archival holdings and manuscript collections. Most universities have archival holdings that chronicle the business of the university. Some universities also have archives or manuscript collections that focus on one aspect or another of the culture of the state or country in which the university is located. Schools and religious institutions, as well as local studies and history collections, museums and research institutions may all hold archives.

The reason for highlighting the breadth and depth of archives is to give some idea of the difficulties facing archival researchers. Some of these archives hold vast quantities of records. For example, the Vatican Secret Archive has upwards of 52 miles of archival shelving. An increasing number of archives are now accepting digital transfers, which can also present challenges for display and access.

Archival research methodologies[]

Archival research lies at the heart of most academic and other forms of original historical research; but it is frequently also undertaken (in conjunction with parallel research methodologies) in other disciplines within the humanities and social sciences, including literary studies, rhetoric,[4][5] archaeology, sociology, human geography, anthropology, psychology, and organizational studies.[6] It may also be important in other non-academic types of enquiry, such as the tracing of birth families by adoptees, and criminal investigations. Data held by archival institutions is also of use in scientific research and in establishing civil rights.

In addition to discipline, the kind of research methodology used in archival research can vary depending on its organization and its materials. For example, in an archives that has a large number of materials still unprocessed, a researcher may find consulting directly with archive staff who have a clear understanding of collections and their organization to be useful as they can be a source of information regarding unprocessed materials or of related materials in other archives and repositories.[7] When an archive is not entirely oriented towards one or relevant to a single discipline, researchers, for example genealogists, may rely upon formal or informal networks to support research by sharing information about specific archives' organization and collections with each other.[8][9]

Conducting research at an archive[]

Archival research is generally more complex and time-consuming than secondary research, presenting challenges in identifying, locating and interpreting relevant documents. Although archives share similar features and characteristics they can also vary in significant ways. While publicly funded archives may have mandates that require them to be as accessible as possible, other kinds, such as corporate, religious, or private archives, will have varying degrees of access and discoverability.[6] Some materials may be restricted in other ways, such as on those containing sensitive or classified information, unpublished works, or imposed by agreements with the donor of materials.[10][11][12] Furthermore, archival records are often unique, and the researcher must be prepared to travel to reach them. Even when materials are available in digital formats there may be restrictions on them that prohibit them from being accessed off-site.

Locating archival collections[]

Prior to online search, union catalogs were an important tool for finding materials in libraries and archives. In the United States, the National Union Catalog and the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections have been used by researchers to locate archives although much of its information has since been migrated to online systems.

An increasing number of archival institutions can be found via an online search. In addition, portals such as Europeana, the Digital Public Library of America and the National Library of Australia's Trove provide links to member institutions.

In the UK, JISC hosts the ArchivesHub, while the OCLC's ArchiveGrid provides an international portal for mostly library based institutions, which use MARC as a cataloguing tool for their holdings. The Association of Canadian Archivists (ACA) has partnered with the software company Artefactual to create ArchivesCanada, while the Australian Society of Archivists have used the same software for their Directory of Archives in Australia. Many other online search tools have been made available to facilitate search and discovery, including the Location Register of English Literary Manuscripts and Letters, the Janus guide to archival materials in institutions in Cambridge, UK, and CARTOMAC: Archives littéraires d'Afrique.

If an archives cannot be found through online search or a publicly listed collection a researcher may have to track down its existence through other means, such as following other researcher's citations and references. This is particularly true for materials held by corporations or other organizations that may not employ an archivist and thus be unaware of the extent or contents of their materials.[6]

In very restricted archives, access may be restricted only to individuals with certain credentials or affiliations with institutions like universities and then only to those of a certain level. Those lacking the necessary credentials may need to request letters of introduction from an individual or institution to provide to the archive.[13]

Locating materials within archives[]

Archives usually contain unique materials and their organization may also be entirely unique or idiosyncratic to the institution or organization that maintains them. This is one important distinction with libraries where material is organized according to standardized classification systems. Traditionally, archives have followed the principle of respect des fonds in which the provenance and original order is maintained although some rearrangement, physical or intellectual, may be done by the archivist to facilitate its use.[14][15] A basic guideline for archival description is the International Standard of Archival Description (General) (ISAD/G or ISAD), produced by the International Council on Archives (ICA). American institutions may also be guided by Describing Archives: a content standard (DACS) and in Canada by the Rules of Archival Description (RAD). Understanding how archival descriptions and finding aids are constructed is known as archival intelligence.[16][17]

In addition to these standards and rules for creating hard copy and online listings and catalogues, archivists may also provide access to their catalogues through APIs or through the encoding standards EAD (Encoded archival description) (relating to the fonds, series, and items) and EAC (Encoded archival context)(the organisations and people that created the archives).

Finding aids are a common reference tool created by archivists for locating materials. They come in a variety of forms, such as registers, card catalogs, or inventories.[18] Many finding aids to archival documents are now hosted online as web pages or uploaded as documents, such as at the Library of Congress' Rare Book & Special Collections. The level of detail in finding aids can vary from granular item-level descriptions to coarse collection-level descriptions.[19][20] If an archive has a large backlog of unprocessed materials, there may not be any kind of finding aid at all.[21] From around 2005, an ideology known as "More Product, Less Process", or MPLP, has been adopted by many North American collecting archives seeking to reduce processing time or alleviate backlogs to provide access to materials sooner, the results of which may be minimally described finding aids.[22]

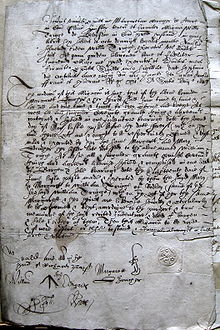

Although most archive repositories welcome researchers, and have professional staff tasked with assisting them, the large quantity of records means that finding aids may be of only limited usefulness: the researcher will need to hunt through large quantities of documents in search of material relevant to his or her particular enquiry. Some records may be closed to public access for reasons of confidentiality; and others may be written in archaic handwriting, in ancient or foreign languages, or in technical terminology. Archival documents were generally created for immediate practical or administrative purposes, not for the benefit of future researchers, and additional contextual research may be necessary to make sense of them. Many of these challenges are exacerbated when the records are still in the custody of the generating body or in private hands, where owners or custodians may be unwilling to provide access to external enquirers, and where finding aids may be even more rudimentary or non-existent.

Consulting archival materials[]

On-site[]

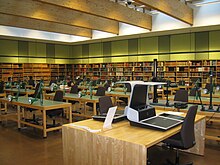

Archival materials are usually held in closed stacks and non-circulating.[23] Users request to see specific materials from the archives and may only consult them on-site.[24][25] After locating the relevant record location using a finding aid or other discovery tool a user may then have to submit the request to the archives, such as using a request form.[26] If an archives has part of its holdings located in a separate building or facility, it make take days or weeks to retrieve materials, requiring a user to submit their requests in advance of an on-site consultation.[27]

A reading room is a space, usually within or near the archive, where users can consult archival materials under staff supervision. The unique, fragile, or sensitive nature of some materials sometimes requires the certain kinds of restrictions on their use, handling, and/or duplication. Many archives restrict what kinds of items can be brought into a reading room from outside, such as pencils, notepads, bags, and even clothing, to guard against theft or risk of damage to materials.[28] Further restrictions may be placed on the number of materials that can be consulted at any given time, such as limiting a user to one box at a time and requiring all materials to be laid flat and visible at all times.[29] Some archives provide basic supplies including scrap paper and pencils or foam wedges for supporting unusually large materials.[4] Duplication services may be available at the archive although the policies, costs, and time required can vary.[30][31] Increasingly, archives also allow users to use their own devices, such as handheld cameras, cell phones, and even scanners, to duplicate materials.[26][32] The use of white or any other glove, while popular in television programs, is not necessarily required for handling archival documents, due to concerns about fragility of pages and text.[33] They may be required for handling volumes with poor bindings, if the gloves are removed for the internal pages to prevent transfer of dirt and other material, and should be used when handling photographs. Always check with the archivist as to whether gloves are required or not.

Archives may also provide access to content via microfilm (including fiche and other formats) due to the fragility or popularity of the original archive. Digital copies may also be provided for the same reason. Before asking for access to the original, make sure that the items that have been reformatted are suitable for the use you require. Reasons for asking for access to original content might included the need to view a colour image (architectural perspective and elevation drawings, maps and plans, etc.) or for accessibility reasons (minor visual vertigo is usually not considered a reason for access to originals, as the effect can be mitigated by slower perusal of the film).

Some materials may contain information that concerns the privacy and confidentiality of living individuals, such as medical and student records, and demand special care. Materials that might contain personally identifiable information, such as social security numbers or names, must be handled appropriately, and an archive might provide redacted copies of materials or deny access to materials entirely due to privacy or other legislative concerns.[34][35]

Off-site and electronic materials[]

More and more archival materials are being digitized or are born-digital enabling them to be accessed off-site through the internet or other networked services. Archives that have digital materials accessible to the public may make their holdings discoverable to internet search engines by sharing or exposing their electronic catalogs and/or metadata, using standards like the Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH). Some institutions have online portals where users can freely access digital materials that have been made available by the archive such as the Archives of the New York Public Library or the Smithsonian Institution Archives. Governments and their related institutions may use these "electronic", or "virtual", reading rooms to upload documents and materials that have been requested by the public such as through FOIA requests or in accordance with records disclosure policies.[36][37][38]

References[]

- ^ International Council on Archives. "Multilingual Archival Terminology". International Council on Archives.

- ^ Society of American Archivists. "A glossary of archival and records terminology".

- ^ Archive.gov. National Records and Archive Administration, 1 December 2009. Web. 5 December 2009 <https://www.archives.gov/research/start/>.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Working in the archives : practical research methods for rhetoric and composition. Ramsey, Alexis E., 1979-. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. 2010. ISBN 9781441645975. OCLC 613205862.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ L'Eplattenier, Barbara E. (2009). "An Argument for Archival Research Methods: Thinking Beyond Methodology". College English. 72 (1): 67–79. JSTOR 25653008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Welch, Catherine (January 2000). "The archaeology of business networks: the use of archival records in case study research". Journal of Strategic Marketing. 8 (2): 197–208. doi:10.1080/0965254x.2000.10815560.

- ^ Working in the archives : practical research methods for rhetoric and composition. Ramsey, Alexis E., 1979-. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. 2010. pp. 82–83. ISBN 9781441645975. OCLC 613205862.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ Duff, Wendy; Johnson, Catherine (January 2003). "Where Is the List with All the Names? Information-Seeking Behavior of Genealogists". The American Archivist. 66 (1): 79–95. doi:10.17723/aarc.66.1.l375uj047224737n.

- ^ Yakel, Elizabeth (2004). "Seeking Information, Seeking Connections, Seeking Meaning: Genealogists and Family Historians". Information Research. 10 (1).

- ^ Anonymous (26 April 2012). "Collections Access Policies". Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "General Information about Restricted Records". National Archives. 15 August 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ "Copyright and Unpublished Material | Society of American Archivists". www2.archivists.org. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ R., Hill, Michael (1993). Archival strategies and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. ISBN 978-0803948242. OCLC 28668848.

- ^ "Archives and Records Management Resources". National Archives. 15 August 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "1. What are Arrangement and Description?". scaa.usask.ca. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "Do you have archival intelligence".

- ^ Yakel, Elizabeth; Torres, Deborah (January 2003). "AI: Archival Intelligence and User Expertise". The American Archivist. 66 (1): 51–78. doi:10.17723/aarc.66.1.q022h85pn51n5800.

- ^ "finding aid | Society of American Archivists". www2.archivists.org. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ "Archive Descriptions - Archives Hub". archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ "level of description | Society of American Archivists". www2.archivists.org. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ Working in the archives : practical research methods for rhetoric and composition. Ramsey, Alexis E., 1979-. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. 2010. pp. 81. ISBN 9781441645975. OCLC 613205862.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ Working in the archives : practical research methods for rhetoric and composition. Ramsey, Alexis E., 1979-. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. 2010. pp. 65–66. ISBN 9781441645975. OCLC 613205862.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ R., Hill, Michael (1993). Archival strategies and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. p. 24. ISBN 978-0803948242. OCLC 28668848.

- ^ "Using the Archives | University Archives Blog". archives.library.ubc.ca. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "Archive of World Music". Harvard Library. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Military Archives - The National Institute for Defense Studies". www.nids.mod.go.jp. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "Research Visit FAQs". National Archives. 11 February 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Archives, The National. "What can I take into the reading rooms? - The National Archives". The National Archives. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "Regulations for NARA Researchers". National Archives. 15 August 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "A Survival Guide to Archival Research: | Perspectives on History | AHA". www.historians.org. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "Reproduction Orders". Hoover Institution. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "Information for Researchers". National Archives. 15 August 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Baker, Cathleen A.; Silverman, Randy (December 2005). "Misperceptions about White Gloves" (PDF). International Preservation News. 37: 4–16.

- ^ Taube, Daniel O.; Burkhardt, Susan (March 1997). "Ethical and Legal Risks Associated With Archival Research". Ethics & Behavior. 7 (1): 59–67. doi:10.1207/s15327019eb0701_5. PMID 11654858.

- ^ "[Ask an Archivist]: When to Restrict Personally Identifiable Information (PII)". SNAP Section. 17 February 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "NARA Electronic Reading Room/FOIA Library". National Archives. 31 August 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "Records Request Reading Room". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ "FOIA: Reading Room - Golden Gate National Recreation Area (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

External links[]

- National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), United States of America

- NARA: "Research Our Records"

- The National Archives (TNA), United Kingdom

- Trace Your Birth Family In The UK

- "Archive skills and tools for historians" - Making History (Institute of Historical Research, University of London)

- Society of American Archivists: Using Archives: A Guide to Effective Research

LibGuides on Archival Research[]

- Guide to Archival Research (Dalhouse University)

- Archival Research Guide (Georgetown University Library)

- A Guide to Archival Research (Emory Libraries)

- Introduction to Archival Research (Duke University Libraries)

- Archival Research: Why Archival Research (Georgia State University)

- Doing Archival Research (Williams College)

- Conducting Archival Research (University of the Witwatersrand)

- Archives

- Historiography

- Research methods

- Evidence