Arthur Mee

This article includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2016) |

Arthur Mee | |

|---|---|

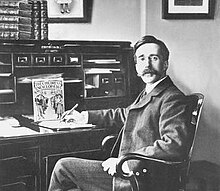

Arthur Mee with The Children's Encyclopædia. | |

| Born | 21 July 1875 Stapleford, Nottinghamshire, England |

| Died | 27 May 1943 (aged 67) London, England |

| Occupation | Writer, journalist, educator |

Arthur Henry Mee (21 July 1875 – 27 May 1943) was an English writer, journalist and educator. He is best known for The Harmsworth Self-Educator, The Children's Encyclopædia, The Children's Newspaper, and The King's England. The tone is looking back to the years immediately after the Great War, even during publication of volumes in the 1940s. He produced other works, most of which had what would today be described as an overly patriotic tone, particularly when discussing the countryside or subjects from history.

Early life[]

He was born on 21 July 1875 at Stapleford near Nottingham, England, the second of the ten children of Henry Mee (b. 1852), railway fireman, and his wife, Mary (née Fletcher). As a boy he earned money from reading the reports of Parliament to a local blind man.

Career[]

Mee left school at 14 to join a local newspaper, where he became an editor by age 20. He contributed many non-fiction articles to magazines and joined the staff of The Daily Mail in 1898. He was made literary editor five years later.

In 1903 he began working for publisher Alfred Harmsworth's Amalgamated Press. He was appointed general editor of The Harmsworth Self-Educator (1905–1907),[1] in collaboration with John Hammerton.

In 1908 he began work on The Children's Encyclopædia, which came out as a fortnightly magazine. The series was published and bound in eight volumes soon afterwards, and later expanded to ten volumes. After the success of The Children's Encyclopædia, he started the first newspaper published for children, the weekly Children's Newspaper, which was published until 1965.

Mee also wrote London – Heart of the Empire and Wonder of the World, which became a very popular book.

Although he made money from these works, he did not receive a fair share.[2]

He had a large house built overlooking the hills near Eynsford in Kent. Its development from design to the final building was depicted in later editions of The Children's Encyclopædia.

Mee had one child, but, despite his work, declared that he had no particular affinity with children. His works for them suggest[to whom?] that his interest was in trying to encourage the raising of a generation of patriotic and moral citizens. He came from a Baptist upbringing, and supported the temperance movement.[citation needed]

Death and legacy[]

He died in London aged 67. His books continued to be published after his death, most notably The King's England, a guide to the counties of England. Mee's works were successful abroad. The Children's Encyclopædia was translated into Chinese and sold well in the United States under the title The Book of Knowledge.

Mee exhibited a number of prejudices in his writing, notably anti-Catholic and anti-intellectual (which may best be illustrated by his treatment of Alexander of Hales in the Gloucestershire volume of the 'King's England'). His writing dwells on the casualties of the Great War.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Arthur Mee's Children's Encyclopaedia". The Alfred Deakin Prime Ministerial Library. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ Hammerton, John (1946). Child of Wonder: An Intimate Biography of Arthur Mee. Hodder & Stoughton.

Sources[]

- Gillian Elias (1993) Arthur Mee – Journalist in Chief to British Youth

- Maisie Robson (2003) Arthur Mee's Dream of England

- Enchanted Land: Half-a-Million Miles in the King's England, Introductory Volume to the UK series known as The King's England – (A New Domesday Book of 10,000 Towns and Villages); details of all the 41 titles obtained from a copy of The King's England series, originally published by Hodder and Stoughton, London, which were illustrated with 10,000 places and 6,000 photographs commencing about 1936

Further reading[]

- The World of the Edwardian Child, as seen in Arthur Mee's Children's Encyclopædia, 1908–1910 by Michael Tracy (2008) includes more information and a new assessment of Arthur Mee and his work, also that of other contributors to the Encyclopædia, and a summary of Hammerton's biography.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arthur Mee. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Arthur Mee |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Arthur Mee |

- Stapleford Website

- Works by Arthur Mee at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Arthur Mee at Internet Archive

- The Children's Encyclopedia – Online Complete Digital Copy of Volume 1

- Arthur Mee (includes excerpts from The Children's Encyclopedia)

- Brief biography and some criticism

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, retrieved 2 Jan 2008

- Arthur Mee: Encyclopedist BBC Radio 4 biography

- Arthur Mee at Library of Congress Authorities, with 136 catalogue records

- 1875 births

- 1943 deaths

- English children's writers

- English male journalists

- People from Stapleford, Nottinghamshire

- English encyclopedists

- People from Eynsford