Australian Museum

| |

The William Street exterior and Crystal Hall entry to the Australian Museum in 2016 | |

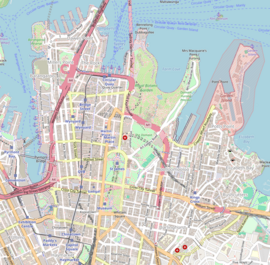

Location within Sydney central business district | |

Former name |

|

|---|---|

| Established | 1827 |

| Location | 1 William Street, Sydney central business district, New South Wales, Australia (Map) |

| Coordinates | 33°52′27″S 151°12′48″E / 33.8743°S 151.2134°ECoordinates: 33°52′27″S 151°12′48″E / 33.8743°S 151.2134°E |

| Type | Natural history and anthropology |

| Director | Kim McKay AO |

| Public transit access |

|

| Website | australian |

Building details | |

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style |

|

| Construction started | 1846 |

| Completed | 1857 |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Sydney sandstone |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect |

|

| Architecture firm | New South Wales Colonial Architect |

| Official name | Australian Museum |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 805 |

| Type | Other – Education |

| Category | Education |

The Australian Museum is a heritage-listed museum at 1 William Street, Sydney central business district, New South Wales, Australia. It is the oldest museum in Australia,[1][2] and the fifth oldest natural history museum in the world, with an international reputation in the fields of natural history and anthropology.[3] It was first conceived and developed along the contemporary European model of an encyclopedic warehouse of cultural and natural history and features collections of vertebrate and invertebrate zoology, as well as mineralogy, palaeontology and anthropology. Apart from exhibitions, the museum is also involved in Indigenous studies research and community programs. In the museum's early years, collecting was its main priority, and specimens were commonly traded with British and other European institutions. The scientific stature of the museum was established under the curatorship of Gerard Krefft, himself a published scientist.

The museum is located at the corner of William Street and College Street in the Sydney central business district, in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, and was originally known as the Colonial Museum or Sydney Museum. The museum was renamed in June 1836 by a sub-committee meeting, when it was resolved during an argument that it should be renamed the "Australian Museum".[4] The Australian Museum building and its collection was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[5] The museum is mentioned in the poem William Street by notable Australian poet Henry Lawson.

Its current CEO and Executive Director is Kim McKay AO.

Establishment[]

The establishment of a museum had first been planned in 1821[6] by the Philosophical Society of Australasia, and although specimens were collected, the Society folded in 1822. An entomologist and fellow of the Linnean Society of London, Alexander Macleay, arrived in 1826. After being appointed New South Wales Colonial Secretary, he began lobbying for a museum.

The museum was founded in 1827 by Earl Bathurst, then the Secretary of State for the Colonies, who wrote to the Governor of New South Wales of his intention to found a public museum and who provided £200 yearly towards its upkeep.[7][8] In 1832[clarification needed] George Bennett, curator of the Australian Museum, explained the role of the museum:

"Here, in a public museum, the remains of the arts, etc., as existing among them, may be preserved as lasting memorials of the former races inhabiting the lands, when they have ceased to exist."

— George Bennett, Curator, 1835 – 1841.

Australia's first museum was a primary conduit through which colonial expansion was represented to the general public. This was occurring even as the dispossession and destruction of Aboriginal life and land continued unabated. Museums were seen as mausoleums for Indigenous culture. Indigenous peoples themselves, needless to say, have historically been silenced in responding to these representations. Early colonial museum practices saw European and Australian museum representations of Indigenous Australians that reiterated and reinforced the political and social norms and agendas of the dominant society. These representations have seen Indigenous Australians portrayed as primitive people, aggressive barbarians, nature's children and of course as noble savages.[9][5]

Building[]

The heritage-listed[5] building has evolved to encompass a range of different architectural styles[10][11] and when its building expanded, it was often in conjunction with an expansion of the collections.

The first location of the museum in 1827 was probably a room in the offices of the Colonial Secretary, although over the following thirty years it had several other locations in Sydney, until it moved into its current home in 1849. The Long Gallery is part of the wing designed by New South Wales Colonial Architect Mortimer Lewis, and the earliest building on the site, c. 1846.[5][2][9] This is a handsome building of Sydney sandstone in the Greek Revival style on the corner of College and William Streets, opposite Hyde Park, designed by the Colonial Architect James Barnet, and it was first opened to the public in May 1857.[8]

In order to accommodate the expanding collections of the museum, Barnet was responsible for the construction of the neoclassical west wing along William Street in 1868. A third storey was added to the north Lewis wing in 1890, bringing cohesion to the building design.[12]

In 1963, the floor space of the museum almost doubled when Joseph van der Steen under the Government Architect, Edward Farmer, designed a six-story extension linked to the Lewis building for the scientific and research collections, the reference library and a public restaurant. There were also two basement floors providing workspace for scientific staff. This International Style extension became known as the Parkes/Farmer eastern wing. In 1977, to mark the Museum's 150th anniversary, bronze lower case letters were added to the façade identifying the building as "The Australian Museum".

In 2008 a significant expansion took place on the College street site with the addition of the new Collection and Research building which added 5000 square metres of office, laboratory and storage areas for scientists. In the same year two new permanent galleries were opened, "Dinosaurs"[13] and "Surviving Australia".[14]

In 2015, the museum's carbon-neutral glass box entryway known as the "Crystal Hall" was opened. Designed by Neeson-Murcutt, it returned the entry to William Street and provided access via a suspended walkway.[15][16] In December 2016 the Museum made public a $285 million master plan proposing to greatly expand its available exhibition space, by adding a 13-storey building on the block's east, adding a large central glazed atrium space.[17][5]

Administration[]

The museum was administered directly by the colonial government until June 1836, until the establishment of a Committee of Superintendence of the Australian Museum and Botanical Garden. Sub-committees were established for each institution. Members of these committees were generally the leading members of the political and scientific classes of Sydney; and scions of the Macleay served until 1853, at which point the committee was abolished. In that year, the government enacted the Australian Museum Act, thereby incorporating it and establishing a board of trustees consisting of 24 members. William Sharp Macleay, the former committee chairman, continued to serve as the chairman of this committee.[18]

Curators and directors[]

The position of "curator" was renamed "director and curator" in 1918 and from, 1921 "director". In 1948, the "scientific assistants" (the scientific staff) were redesignated "curators" and "assistant curators". In 1983, during a period of reorganisation, the position of curator was renamed as "collection manager".

| Order | Officeholder | Position title | Start date | End date | Term in office | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | William Holmes | Custodian | 16 June 1829 | 1835 | 5–6 years | Holmes accidentally shot himself while collecting specimens at Moreton Bay in August 1831.[19] |

| 2 | George Bennett | Curator | 1835 | 1841 | 5–6 years | Bennett was the first to catalogue the museum's collections. |

| 3 | The Revd W. B. Clarke | 1841 | 1843 | 1–2 years | ||

| 4 | William Sheridan Wall | 1845 | 1858 | 12–13 years | Long time collector to the Museum. Wrote and illustrated History and Description of a New Sperm Whale (Sydney 1851)[20] | |

| 7 | Gerard Krefft | 1861 | 1874 | 12–13 years | ||

| 8 | Edward Pierson Ramsay | 1874 | 1894 | 19–20 years | Ramsay greatly increased the recruitment of scientific staff within the institution. The museum's catalogues, first documented by Bennett, were the first scientific publications by the museum, but with the addition of science staff and, thereby, research output, in 1890 Ramsay started the Records of the Australian Museum, a publication which continues to the present.[21] | |

| 9 | Robert Etheridge Jr | 1895 | 1918 | 23–24 years | ||

| Director and Curator | 1918 | 1919 | ||||

| 10 | Charles Anderson | Director | 1921 | 1940 | 18–19 years | |

| 11 | Dr Arthur Bache Walkom | 1941 | 1954 | 12–13 years | ||

| 12 | Dr John William Evans | 1954 | 1966 | 11–12 years | ||

| 13 | Frank Talbot | 1966 | 1975 | 8–9 years | ||

| 14 | Dr Desmond Griffin | 1976 | 1998 | 21–22 years | ||

| 15 | Dr Michael Archer | 1999 | 2004 | 4–5 years | ||

| 16 | Frank Howarth | 2004 | 2014 | 9–10 years | ||

| 17 | Kim McKay AO | 2014 | present | 6–7 years | McKay is the first woman to hold the position.[22][23] |

Collections and programs[]

After a run of field collecting activities by the scientific staff in the 1880s and 1890s, field work ceased until after the First World War. In the 1920s, new expeditions were launched to New Guinea, the Kermadec Islands and Santa Cruz in the Solomon Islands, as well as to many parts of Australia, including the Capricorn Islands off the coast of Queensland.[24](p137)

During the 19th century, galleries had mainly included large display cases overly filled with specimens and artifacts. During the 1920s museum displays grew to include dioramas showing habitat groups, but otherwise the Museum was largely unchanged during the period beginning with the curatorship of Robert Etheridge Jr (1895–1919), until 1954, with the appointment of John Evans. Under his direction, additional buildings were built, several galleries were entirely overhauled, and a new Exhibitions department was created. The size of the education staff was also radically increased. By the end of the 1950s, all of the galleries had been completely overhauled.

The museum's growth in the field of scientific research continued with a new department of environmental studies, created in 1968.[25] The museum support society, The Australian Museum Society (TAMS), now known as Museum Members) was formed in 1972, and in 1973 the Lizard Island Research Station (LIRS), was established near Cairns.

The Australian Museum Train, an early outreach project, was officially launched on 8 March 1978. The train was described as "a wonderful new concept of the travelling circus! The only difference is that the travelling Museum Train will bring school children and the people of NSW into contact with the wonders of nature, evolution and Wildlife."[citation needed] The two-carriage train was renovated and refurbished at Eveleigh Carriage Works, and fitted out with exhibits by the Australian Museum at a cost of about $100,000. One carriage displayed the evolution of the earth, animals and man. The second carriage was a lecture and visual display area.[26] The train ceased operations in December 1988 but the museum's outreach work in regional communities continues.

In 1991, the museum established a commercial consulting and project management group, the Australian Museum Business Services (AMBS), now known as Australian Museum Consulting. In 1995, the museum established new research centres in conservation, biodiversity, evolutionary research, geodiversity and "People and Places". These research centres have now been incorporated into the museum's natural science collection programs. In 1998, the djamu gallery opened at Customs House, Circular Quay, the first major new venue for the museum beyond College Street site. A series of exhibitions on Indigenous culture were displayed until the gallery closed at the end of 2000.

In 2001 two rural associate museums were established, The Age of Fishes Museum in Canowindra and the Australian Fossil and Mineral Museum in Bathurst which includes the mineral and dinosaur Somerville Collection donated by Warren Somerville.

In 2002, ICAC launched Operation Savoy to investigate thefts of the zoological collections by a museum employee.[27]

In 2011 the museum launched its first Mobile App – "DangerOZ"[28] – about Australia's most dangerous animals.

In September 2013, the Australian Museum Research Institute (AMRI) was launched. AMRI's purposes are:

- to provide a focal point for the many researchers working in the museum

- to facilitate collaborations with government research agencies, universities, gardens, zoos and other museums

- to showcase the important scientific research that is being done at the museum, focusing on climate change impacts on biodiversity; the detection and biology of pest species; understanding what constitutes and influences effective biodiversity conservation.[29]

Exhibitions[]

The museum has hosted exhibitions since 1854 to the present day, including permanent, temporary and touring exhibitions, such as "Dinosaurs from China", "Festival of the Dreaming", "Beauty from Nature: Art of the Scott Sisters" and "Wildlife Photographer of the Year".[30] In 2012–13 the museum hosted "Alexander the Great" which exhibited the largest collection of treasures ever to come to Australia from the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia.[31]

When the Crystal Hall was launched as the museum's new entrance in August 2015, the former foyer, the Barnet Wing, became the permanent gallery housing "Wild Planet" – a display of over 400 animals that explores and explains evolution and the tree of life.[32]

In 2015, "Trailblazers: Australia's 50 greatest explorers" opened, honouring the work of Bourke and Wills, Nancy Bird Walton, Dick Smith, Jessica Watson and Tim Jarvis, among others.

Other audience engagement programs include live displays to help demonstrate the behaviours and adaptations of animals, video conferencing and "Museum in a Box" for schoolchildren, as well as cultural heritage initiatives for Pacific youth and Indigenous Australians.[33]

Jurassic Lounge[]

Established in early 2011 by the Australian Museum and non-profit company The Festivalists, Jurassic Lounge is a re-inauguration of the creative use of museum spaces for contemporary arts display. [34] Combining events, live music, art, cultural displays, and new media with standard exhibition space in the museum precinct, Jurassic Lounge is a seasonal display-event held on Tuesdays for two seasons annually.[35] Jurassic lounge first opened on 1 February 2011.[36] It is held from 5.30pm to 9.30pm at the Australian Museum which is located on 6 College Street Sydney, Australia.[37] It allows the public to discover Sydney's hottest new emerging artists, musicians and performers. Last year's line ups included a burlesque show, a silent disco, live painting, a photobooth, interaction with museum animals (snake and stick insects).[38]

Heritage listing[]

As at 14 November 2014, the Australian Museum buildings house the first public museum inaugurated in Australia, one of Australia's oldest scientific and cultural institutions. Conceived and developed initially along the contemporary European model of an encyclopedic warehouse of cultural and natural history, the museum buildings evolved as the institution evolved, partly in response to its visiting public, to pursue and expand knowledge of the natural history of Australia and the nearby pacific region. The museum continues to occupy the site provided, and the building constructed, as its first permanent home, commenced in 1846 and opened to the public in 1857. The extended and enlarged complex of buildings which now provide its principal exhibition, administrative and research accommodation reflect the growth of the institution and its prestige, as well as the evolving attitudes of Australian Government and society to science and research.[5]

The Museum's various buildings further comprise a unique aggregation of work by successive colonial and Government Architects of New South Wales, exhibiting:

- changes in the philosophy and functional requirements of museum design

- changing stylistic influences and design approaches in architecture from the early 19th century to the present, and

- corresponding developments in building technology, materials and craftsmanship.[5]

Individually the various elements of the Museum complex remain significantly intact, with potential for enhancement of their cultural significance through conservation techniques, though conflicts exist between conservation of fabric and contemporary use, particularly exhibition techniques. Of special note are the exteriors and principal interiors of the three earliest wings of the complex, which despite varying degrees of alteration, remain in substantial original condition. The interlinked exhibition galleries comprise an important group of 19th and early 20th century public interests.[5]

Through its development, the Museum complex has assumed a prominent stature in the townscape of Sydney. With its frontage to William and College Street, the Museum commands the eastern reaches of Hyde Park and forms and extension of the principal historic civic and religious precincts adjoining the northern boundaries of the park in Macquarie and College streets. Through recent expansion the museum site includes the former grounds and two surviving buildings of the William Street National School, which, established in 1851, is one of the earlier public schools continued in educational use for almost 100 years.[5]

Australian Museum was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[5]

2020 Upgrade[]

At the end of 2020, after being closed for 15 months, the 200 year old Museum re-opened following a major upgrade. Subsequent to its refurbishment, Museum entry will be free for the public and the building will provide a physical space that "equals the importance of the collection and the scientific research" done there.[3]

Gallery[]

Butterflies in a display case

Human and Horse Skeletons displayed in a lifelike pose (2007)

A display of African metalwork art, 2007

A display case of some stuffed Australian bird specimens, 2007

Display on the skeletal structure of snakes and other reptiles (2007)

Modern Aboriginal art on show at the Museum in 2007

Museum at night

See also[]

- The Lewis Collection

- List of museums in Australia

- National Museum of Australia

- Museum of Sydney

References[]

- ^ "A Short History of the Australian Museum". Australian Museum.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Design 5, 2016, p.1

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meacham, Steve (27 November 2020). "Dinosaurs to the rescue as new life awakens for an old museum". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ "Colonial Museum (1827–1834) / Australian Museum (1834– ), NSW Government State Records". Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j "Australian Museum". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00805. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Thomsett, Susan (January 1993). "A History of the Pacific Collections in the Australian Museum, Sydney". Pacific Arts. 7 (7): 12–19. JSTOR 23409019.

- ^ Watson, F. (15 May 2012). "Bathurst's Letter". Historical Records of Australia, Series I, Vol.13. Australian Museum. p. 210. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Finney, Vanessa (30 May 2012). "A short history of the Australian Museum". Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hammond, 2009, 1

- ^ "Museum website "Our buildings through time"". Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ Proudfoot, Helen; Otto Cserhalmi & Partners (1984), The Australian Museum : a conservation analysis of the complex and its site with a statement of its significance, s.n.], retrieved 22 August 2013

- ^ Jahn, Graham (2006). Guide to Sydney Architecture (Architecture Guides). Watermark Press. ISBN 978-0949284327. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Dinosaur Gallery". Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ "Surviving Australia Exhibition". Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Croaker, Trisha (10 September 2015). "Ancient footprints lead way into new era at the Australian Museum". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ Meacham, Steve (29 May 2015). "The Australian Museum's radical transformation". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 25 December 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ^ Power, 2016

- ^ Docker, Rose (15 May 2012). "The Museum's Early Days". Australian Museum. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ "A Birth of a Museum". Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ William Sheridan Wall Design and Art Australia Online

- ^ "Records of the Australian Museum". Australian Museum. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ "New Director". Australian Museum. 2014.

- ^ Meacham, Steve (29 May 2015). "The Australian Museum's radical transformation". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 25 December 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ Strahan, 1979.

- ^ "Curators and Directors of the Australian Museum". Australian Museum. 16 November 2009. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ Network, published by the Railways of Australia Committee, May 1978, p.31.

- ^ Fickling, David (25 September 2003). "Pest controller stole museum specimens". The Guardian.

- ^ "DangerOz App". Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Crossley, Merlin. "Right at the museum: collections give clues on climate change". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ "Exhibitions Timeline". Australian Museum. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Alexander the Great: 2000 Years of Treasures". The Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ "Australian Museum's Wild Planet exhibition brings dead beasts to life". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 15 December 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ "Australian Museum Annual Report 2011-12" (PDF). Australian Museum. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ https://australian.museum/BlogPost/Audience-Research-Blog/Jurassic-Lounge-A-Case-Study. Retrieved 16 April 2019. Missing or empty

|title=(help)[dead link] - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Jurassic Lounge". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Jurassic Lounge Australian Museum – Spring 2012". www.weekendnotes.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

Bibliography[]

- Attraction Homepage (2007). "Australian Museum".

- Chris Bennett of Evolving Picture (2014). Australian Museum Sydney: photographic survey of existing site features December 2014.

- Clive Lucas Stapleton & Partners Pty Ltd (2005). The Australian Museum, Sydney, Conservation Management Plan.

- Cultural Resources Management (2008). The Australian Museum Sydney : archaeological investigation collections & research building.

- Design 5 Architects (2016). Long Gallery, Australian Museum – Exemption from Development Consent – upgrade and repair works.

- Hammond, Gina (2009). 'The Curious Case of the Living Dead', in "History Council of NSW Bulletin" Autumn 2009.

- McDonald McPhee Pty Ltd. (1994). Heritage Assessment, Barnet Wing, Australian Museum.

- Power, Julie (2016). 'Museum's ambitious plan – exclusive: $285m proposal for a grand exhibition space'.

- Strahan, Ronald (1979). Rare and Curious Specimens: An Illustrated History of the Australian Museum 1827–1979. The Australian Museum. ISBN 0724015248.

- Tourism NSW (2007). "Australian Museum". Archived from the original on 7 September 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

Attribution[]

![]() This Wikipedia article contains material from Australian Museum, entry number 805 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from Australian Museum, entry number 805 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Australian Museum. |

- Official website

- Australian Museum – Sydney.com

- Australian Museum at Google Cultural Institute

- Ellmoos, Laila (2008). "Australian Museum". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 8 October 2015. [CC-By-SA]

- Museums in Sydney

- Government agencies of New South Wales

- Natural history museums in Australia

- Neoclassical architecture in Australia

- James Barnet buildings in Sydney

- New South Wales State Heritage Register sites located in the Sydney central business district

- Mortimer Lewis buildings

- 1827 establishments in Australia

- Sandstone buildings in Australia

- College Street, Sydney