Australian rules football

A ruckman leaps above his opponent to win the hit-out during a ball-up | |

| Highest governing body | AFL Commission |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Football, footy, Aussie rules |

| First played | May 1859 in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

| Registered players | 1,404,176 (2016)[1] |

| Clubs | 25,770 (2016)[1] |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Full |

| Team members | 22 (18 onfield, 4 interchange) |

| Mixed gender | Up to age 14 |

| Type | Outdoor |

| Equipment | Football |

| Glossary | Glossary of Australian rules football |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | Demonstration sport, 1956 Melbourne Olympics |

Australian rules football, also called Australian football or Aussie rules,[2] or more simply football or footy, is a contact sport played between two teams of 18 players on an oval field, often a modified cricket ground. Points are scored by kicking the oval ball between the middle goal posts (worth six points) or between a goal and behind post (worth one point).

During general play, players may position themselves anywhere on the field and use any part of their bodies to move the ball. The primary methods are kicking, handballing and running with the ball. There are rules on how the ball can be handled; for example, players running with the ball must intermittently bounce or touch it on the ground. Throwing the ball is not allowed, and players must not get caught holding the ball. A distinctive feature of the game is the mark, where players anywhere on the field who catch the ball from a kick (with specific conditions) are awarded unimpeded possession.[3] Possession of the ball is in dispute at all times except when a free kick or mark is paid. Players can tackle using their hands or use their whole body to obstruct opponents. Dangerous physical contact (such as pushing an opponent in the back), interference when marking, and deliberately slowing the play are discouraged with free kicks, distance penalties, or suspension for a certain number of matches depending on the severity of the infringement. The game features frequent physical contests, spectacular marking, fast movement of both players and the ball, and high scoring.

The sport's origins can be traced to football matches played in Melbourne, Victoria, in 1858, inspired by English public school football games. Seeking to develop a game more suited to adults and Australian conditions, the Melbourne Football Club published the first laws of Australian football in May 1859, making it the oldest of the world's major football codes.[4][5]

Australian football has the highest spectator attendance and television viewership of all sports in Australia,[6][7] while the Australian Football League (AFL), the sport's only fully professional competition, is the nation's wealthiest sporting body.[8] The AFL Grand Final, held annually at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, is the highest attended club championship event in the world. The sport is also played at amateur level in many countries and in several variations. Its rules are governed by the AFL Commission with the advice of the AFL's Laws of the Game Committee.

Name[]

Australian rules football is known by several nicknames, including Aussie rules, football and footy.[9] In some regions, the Australian Football League markets the game as AFL after itself.[10]

History[]

Origins[]

There is evidence of football being played sporadically in the Australian colonies in the first half of the 19th century. Compared to cricket and horse racing, football was considered a mere "amusement" at the time, and while little is known about these early one-off games, it is clear they share no causal link with Australian football.[12] In Melbourne, Victoria, in 1858, in a move that would help to shape Australian football in its formative years, private schools (then termed "public schools" in accordance with English scholastic nomenclature) began organising football games inspired by precedents at English public schools.[13] The earliest such match, held in St Kilda on 15 June, was between Melbourne Grammar and St Kilda Grammar.[14]

On 10 July 1858, the Melbourne-based Bell's Life in Victoria and Sporting Chronicle published a letter by Tom Wills, captain of the Victoria cricket team, calling for the formation of a "foot-ball club" with a "code of laws" to keep cricketers fit during winter.[15] Born in Australia, Wills played a nascent form of rugby football whilst a pupil at Rugby School in England, and returned to his homeland a star athlete and cricketer. His letter is regarded by many historians as giving impetus for the development of a new code of football today known as Australian football.[16] Two weeks later, one of Wills' friends, cricketer Jerry Bryant, posted an advertisement for a scratch match at the Richmond Paddock adjoining the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG).[17] This was the first of several "kickabouts" held that year involving members of the Melbourne Cricket Club, including Wills, Bryant, W. J. Hammersley and J. B. Thompson. Trees were used as goalposts, and play typically lasted an entire afternoon. Without an agreed-upon code of laws, some players were guided by rules they had learned in the British Isles, while "others by no rules at all".[18]

Another significant milestone in 1858 was a match played under experimental rules between Melbourne Grammar School and Scotch College, held at the Richmond Paddock. This 40-a-side contest, umpired by Wills and Scotch College teacher John Macadam, began on 7 August and continued over two subsequent Saturdays, ending in a draw with each side kicking one goal.[19] It is commemorated with a statue outside the MCG, and the two schools have competed annually ever since in the Cordner–Eggleston Cup, the world's oldest continuous football competition.[20]

Since the early 20th century, it has been suggested that Australian football was derived from the Irish sport of Gaelic football.[21] However, there is no archival evidence in favour of a Gaelic influence, and the style of play shared between the two modern codes appeared in Australia long before the Irish game evolved in a similar direction.[22][23] Another theory, first proposed in 1983, posits that Wills, having grown up amongst Aboriginal people in Victoria, may have seen or played the Aboriginal ball game of Marn Grook, and incorporated some of its features into early Australian football. The evidence that he knew of the game is only circumstantial, and according to biographer Greg de Moore's research, Wills was "almost solely influenced by his experience at Rugby School".[24]

First rules[]

A loosely organised Melbourne side, captained by Wills, played against other football enthusiasts in the winter and spring of 1858.[25] The following year, on 14 May, the Melbourne Football Club was officially established, making it one of the world's oldest football clubs. Three days later, Wills, Hammersley, Thompson and teacher Thomas H. Smith met near the MCG at the Parade Hotel, owned by Bryant, and drafted ten rules: "The Rules of the Melbourne Football Club". These are the laws from which Australian football evolved.[26] The club stated that they aimed to create a simple code suited to the hard playing surfaces around Melbourne, and to eliminate the roughest aspects of English school games—such as "hacking" (shin-kicking) in Rugby School football—to lessen the chance of injuries to working men.[27] In another significant departure from English public school football, the Melbourne rules omitted any offside law.[28] "The new code was as much a reaction against the school games as influenced by them", writes Mark Pennings.[29]

The rules were distributed throughout the colony; Thompson in particular did much to promote the new code in his capacity as a journalist.[30] Australian football's date of codification predates that of any other major football code, including soccer (codified in 1863), rugby union (codified in 1871), American football (codified 1873) and gaelic football (codified in 1877).

Early competition in Victoria[]

Following Melbourne's lead, Geelong and Melbourne University also formed football clubs in 1859.[32] While many early Victorian teams participated in one-off matches, most had not yet formed clubs for regular competition. A South Yarra side devised its own rules.[33] To ensure the supremacy of the Melbourne rules, the first-club level competition in Australia, the Caledonian Society's Challenge Cup (1861–64), stipulated that only the Melbourne rules were to be used.[34] This law was reinforced by the Athletic Sports Committee (ASC), which ran a variation of the Challenge Cup in 1865–66.[35] With input from other clubs, the rules underwent several minor revisions, establishing a uniform code known as "Victorian rules".[36] In 1866, the "first distinctively Victorian rule", the running bounce, was formalised at a meeting of club delegates chaired by H. C. A. Harrison,[37] an influential pioneer who took up football in 1859 at the invitation of Wills, his cousin.[38]

The game around this time was defensive and low-scoring, played low to the ground in congested rugby-style scrimmages. The typical match was a 20-per-side affair, played with a ball that was roughly spherical, and lasted until a team scored two goals.[28] The shape of the playing field was not standardised; matches often took place in rough, tree-spotted public parks, most notably the Richmond Paddock (Yarra Park), known colloquially as the Melbourne Football Ground.[39] Wills argued that the turf of cricket fields would benefit from being trampled upon by footballers in winter,[40] and, as early as 1859, football was allowed on the MCG.[41] However, cricket authorities frequently prohibited football on their grounds until the 1870s, when they saw an opportunity to capitalise on the sport's growing popularity. Football gradually adapted to an oval-shaped field, and most grounds in Victoria expanded to accommodate the dual purpose—a situation that continues to this day.[41]

Spread to other colonies[]

Football became organised in South Australia in 1860 with the formation of the Adelaide Football Club, the oldest football club in Australia outside Victoria.[42] It devised its own rules, and, along with other Adelaide-based clubs, played a variety of codes until 1876, when they agreed to uniformly adopt most of the Victorian rules, with South Australian football pioneer Charles Kingston noting their similarity to "the old Adelaide rules".[43] Likewise, Tasmanian clubs quarrelled over different rules until they adopted a slightly modified version of the Victorian game in 1879.[44] The South Australian Football Association (SAFA), the sport's first governing body, formed on 30 April 1877, firmly establishing Victorian rules as the preferred code in that colony.[45] The Victorian Football Association (VFA) formed the following month.

As clubs began touring the colonies in the late 1870s, the sport spread to New South Wales, and in 1879, the first intercolonial match took place in Melbourne between Victoria and South Australia.[46] In order to standardise the sport across Australia, delegates representing the football associations of South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Queensland met in 1883 and updated the code.[44] New rules such as holding the ball led to a "golden era" of fast, long-kicking and high-marking football in the 1880s, a time which also saw the rise of professionalism, particularly in Victoria and Western Australia[citation needed] (where the code took hold during the colony's gold rushes), and players such as George Coulthard achieve superstardom.[47] Now known as Australasian rules or Australian rules, it became the first football code to develop mass spectator appeal,[46] attracting world record attendances for sports viewing and gaining a reputation as "the people's game".[47]

The sport reached Queensland as early as 1866, and experienced a period of dominance there,[48] but, like in New Zealand and areas of New South Wales north of the Riverina, it struggled to thrive, largely due to the spread of rugby football with British migration, regional rivalries and the lack of strong local governing bodies. In the case of Sydney, denial of access to grounds, the influence of university headmasters from Britain who favoured rugby, and the loss of players to other codes inhibited the game's growth.[49]

Emergence of the VFL[]

In 1896, delegates from six of the wealthiest VFA clubs—Carlton, Essendon, Fitzroy, Geelong, Melbourne and South Melbourne—met to discuss the formation of a breakaway professional competition.[50] Later joined by Collingwood and St Kilda, the clubs formed the Victorian Football League (VFL), which held its inaugural season in 1897. The VFL's popularity grew rapidly as it made several innovations, such as instituting a finals system, reducing teams from 20 to 18 players, and introducing the behind as a score.[51] Richmond and University joined the VFL in 1908, and by 1925, with the addition of Hawthorn, Footscray and North Melbourne, it had become the preeminent league in the country and would take a leading role in many aspects of the sport.

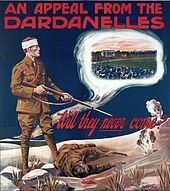

Effects of the World Wars[]

Both World War I and World War II had a devastating effect on Australian football and on Australian sport in general. While scratch matches were played by Australian "diggers" in remote locations around the world, the game lost many of its great players to wartime service. Some clubs and competitions never fully recovered. Between 1914 and 1915, a proposed hybrid code of Australian football and rugby league, the predominant code of football in New South Wales and Queensland, was trialled without success.[52][53] The advent of World War I started a recession of the game in New Zealand, affecting the game's popularity for three-quarters of a century. In Queensland, the state league went into recess for the duration of the war. VFL club University left the league and went into recess due to severe casualties. The WAFL lost two clubs and the SANFL was suspended for one year in 1916 due to heavy club losses. The Anzac Day match, the annual game between Essendon and Collingwood on Anzac Day, is one example of how the war continues to be remembered in the football community.

Interstate football and the ANFC[]

The role of the Australian National Football Council (ANFC) was primarily to govern the game at a national level and to facilitate interstate representative and club competition. The ANFC ran the Championship of Australia, the first national club competition, which commenced in 1888 and saw clubs from different states compete on an even playing field. Although clubs from other states were at times invited, the final was almost always between the premiers from the two strongest state competitions of the time—South Australia and Victoria—and the majority of matches were played in Adelaide at the request of the SAFA/SANFL. The last match was played in 1976, with North Adelaide being the last non-Victorian winner in 1972. Between 1976 and 1987, the ANFC, and later the Australian Football Championships (AFC) ran a night series, which invited clubs and representative sides from around the country to participate in a knock-out tournament parallel to the premiership seasons, which Victorian sides still dominated.

With the lack of international competition, state representative matches were regarded with great importance. The Australian Football Council coordinated regular interstate carnivals, including the Australasian Football Jubilee, held in Melbourne in 1908 to celebrate the game's semicentenary.[54] Due in part to the VFL poaching talent from other states, Victoria dominated interstate matches for three-quarters of a century. State of Origin rules, introduced in 1977, stipulated that rather than representing the state of their adopted club, players would return to play for the state they were first recruited in. This instantly broke Victoria's stranglehold over state titles and Western Australia and South Australia began to win more of their games against Victoria. Both New South Wales and Tasmania scored surprise victories at home against Victoria in 1990.

Towards a national competition[]

The term "Barassi Line", named after VFL star Ron Barassi, was coined by scholar Ian Turner in 1978 to describe the "fictitious geographical barrier" separating large parts of New South Wales and Queensland which predominantly followed the two rugby codes from the rest of the country, where Australian football reigned.[55] It became a reference point for the expansion of Australian football and for establishing a national league.[56]

The way the game was played had changed dramatically due to innovative coaching tactics, with the phasing out of many of the game's kicking styles and the increasing use of handball; while presentation was influenced by television.[57]

In 1982, in a move that heralded big changes within the sport, one of the original VFL clubs, South Melbourne, relocated to Sydney and became known as the Sydney Swans. In the late 1980s, due to the poor financial standing of many of the Victorian clubs, and a similar situation existing in Western Australia in the sport, the VFL pursued a more national competition. Two more non-Victorian clubs, West Coast and Brisbane, joined the league in 1987.[58] In their early years, the Sydney and Brisbane clubs struggled both on and off-field because the substantial TV revenues they generated by playing on a Sunday went to the VFL. To protect these revenues the VFL granted significant draft concessions and financial aid to keep the expansion clubs competitive. Each club was required to pay a licence fee which allowed the Victorian-based clubs to survive.

The VFL changed its name to the Australian Football League (AFL) for the 1990 season, and over the next decade, three non-Victorian clubs gained entry: Adelaide (1991), Fremantle (1995) and the SANFL's Port Adelaide (1997), the only pre-existing club outside Victoria to join the league.[58] In 2011 and 2012, respectively, two new non-Victorian clubs were added to the competition: Gold Coast and Greater Western Sydney.[59] The AFL, currently with 18 member clubs, is the sport's elite competition and most powerful body. Following the emergence of the AFL, state leagues were quickly relegated to a second-tier status. The VFA merged with the former VFL reserves competition in 1998, adopting the VFL name. State of Origin also declined in importance, especially after an increasing number of player withdrawals. The AFL turned its focus to the annual International Rules Series against Ireland in 1998 before abolishing State of Origin the following year. State and territorial leagues still contest interstate matches, as do AFL Women players.[60]

Although a Tasmanian AFL bid is ongoing,[61] the AFL's focus has been on expanding into markets outside Australian football's traditional heartlands.[62] The AFL regularly schedules pre-season exhibition matches in all Australian states and territories as part of the Regional Challenge. The AFL signalled further attempts at expansion in the 2010s by hosting home-and-away matches in New Zealand,[63] followed by China.[64]

Laws of the game[]

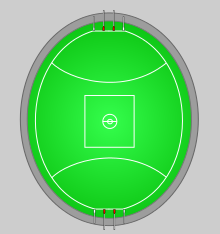

Field[]

Australian rules football playing fields have no fixed dimensions but at senior level are typically between 135 and 185 metres (148 and 202 yd) long and 110 and 155 metres (120 and 170 yd) wide wing-to-wing. The field, like the ball, is oval-shaped, and in Australia, cricket grounds are often used. No more than 18 players of each team (or, in AFL Women's, 16 players) are permitted to be on the field at any time.

Up to four interchange (reserve) players may be swapped for those on the field at any time during the game. In Australian rules terminology, these players wait for substitution "on the bench"—an area with a row of seats on the sideline. Players must interchange through a designated interchange "gate" with strict penalties for having too many players from one team on the field. In addition, some leagues have each team designate one player as a substitute who can be used to make a single permanent exchange of players during a game.

There is no offside rule nor are there set positions in the rules; unlike many other forms of football, players from both teams may disperse across the whole field before the start of play. However, a typical on-field structure consists of six forwards, six defenders or "backmen" and six midfielders, usually two wingmen, one centre and three followers, including a ruckman, ruck-rover and rover. Only four players from each team are allowed within the centre square (50 metres or 55 yards) at every centre bounce, which occurs at the commencement of each quarter, and to restart the game after a goal is scored. There are also other rules pertaining to allowed player positions during set plays (that is, after a mark or free kick) and during kick-ins following the scoring of a behind.

Match duration[]

A game consists of four quarters and a timekeeper officiates their duration. At the professional level, each quarter consists of 20 minutes of play, with the clock being stopped for instances such as scores, the ball going out of bounds or at the umpire's discretion, e.g. for serious injury. Lower grades of competition might employ shorter quarters of play. The umpire signals time-off to stop the clock for various reasons, such as the player in possession being tackled into stagnant play. Time resumes when the umpire signals time-on or when the ball is brought into play. Stoppages cause quarters to extend approximately 5–10 minutes beyond the 20 minutes of play. 6 minutes of rest is allowed before the second and fourth quarters, and 20 minutes of rest is allowed at half-time.

The official game clock is available only to the timekeeper(s), and is not displayed to the players, umpires or spectators. The only public knowledge of game time is when the timekeeper sounds a siren at the start and end of each quarter. Coaching staff may monitor the game time themselves and convey information to players via on-field trainers or substitute players. Broadcasters usually display an approximation of the official game time for television audiences, although some will now show the exact time remaining in a quarter.

General play[]

Games are officiated by umpires. Before the game, the winner of a coin toss determines which directions the teams will play to begin. Australian football begins after the first siren, when the umpire bounces the ball on the ground (or throws it into the air if the condition of the ground is poor), and the two ruckmen (typically the tallest players from each team) battle for the ball in the air on its way back down. This is known as the ball-up. Certain disputes during play may also be settled with a ball-up from the point of contention. If the ball is kicked or hit from a ball-up or boundary throw-in over the boundary line or into a behind post without the ball bouncing, a free kick is paid for out of bounds on the full. A free kick is also paid if the ball is deemed by the umpire to have been deliberately carried or directed out of bounds. If the ball travels out of bounds in any other circumstances (for example, contested play results in the ball being knocked out of bounds) a boundary umpire will stand with his back to the infield and return the ball into play with a throw-in, a high backwards toss back into the field of play.[65]

The ball can be propelled in any direction by way of a foot, clenched fist (called a handball or handpass) or open-hand tap but it cannot be thrown under any circumstances. Once a player takes possession of the ball he must dispose of it by either kicking or handballing it. Any other method of disposal is illegal and will result in a free kick to the opposing team. This is usually called "incorrect disposal", "dropping the ball" or "throwing". If the ball is not in the possession of one player it can be moved on with any part of the body.

A player may run with the ball, but it must be bounced or touched on the ground at least once every 15 metres (16 yd). Opposition players may bump or tackle the player to obtain the ball and, when tackled, the player must dispose of the ball cleanly or risk being penalised for holding the ball unless the umpire rules no prior opportunity for disposal. The ball carrier may only be tackled between the shoulders and knees. If the opposition player forcefully contacts a player in the back while performing a tackle, the opposition player will be penalised for a push in the back. If the opposition tackles the player with possession below the knees (a low tackle or a trip) or above the shoulders (a high tackle), the team with possession of the football gets a free kick.

If a player takes possession of the ball that has travelled more than 15 metres (16 yd) from another player's kick, by way of a catch, it is claimed as a mark (meaning that the game stops while he prepares to kick from the point at which he marked). Alternatively, he may choose to "play on" forfeiting the set shot in the hope of pressing an advantage for his team (rather than allowing the opposition to reposition while he prepares for the free kick). Once a player has chosen to play on, normal play resumes and the player who took the mark is again able to be tackled.

There are different styles of kicking depending on how the ball is held in the hand. The most common style of kicking seen in today's game, principally because of its superior accuracy, is the drop punt, where the ball is dropped from the hands down, almost to the ground, to be kicked so that the ball rotates in a reverse end over end motion as it travels through the air. Other commonly used kicks are the torpedo punt (also known as the spiral, barrel, or screw punt), where the ball is held flatter at an angle across the body, which makes the ball spin around its long axis in the air, resulting in extra distance (similar to the traditional motion of an American football punt), and the checkside punt or "banana", kicked across the ball with the outside of the foot used to curve the ball (towards the right if kicked off the right foot) towards targets that are on an angle. There is also the "snap", which is almost the same as a checkside punt except that it is kicked off the inside of the foot and curves in the opposite direction. It is also possible to kick the ball so that it bounces along the ground. This is known as a "grubber". Grubbers can bounce in a straight line, or curve to the left or right.

Apart from free kicks, marks or when the ball is in the possession of an umpire for a ball up or throw in, the ball is always in dispute and any player from either side can take possession of the ball.

Scoring[]

A goal, worth 6 points, is scored when the football is propelled through the goal posts at any height (including above the height of the posts) by way of a kick from the attacking team. It may fly through "on the full" (without touching the ground) or bounce through, but must not have been touched, on the way, by any player from either team or a goalpost. A goal cannot be scored from the foot of an opposition (defending) player.

A behind, worth 1 point, is scored when the ball passes between a goal post and a behind post at any height, or if the ball hits a goal post, or if any player sends the ball between the goal posts by touching it with any part of the body other than a foot. A behind is also awarded to the attacking team if the ball touches any part of an opposition player, including a foot, before passing between the goal posts. When an opposition player deliberately scores a behind for the attacking team (generally as a last resort to ensure that a goal is not scored) this is termed a rushed behind. As of the 2009 AFL season, a free kick is awarded against any player who deliberately rushes a behind.[66][67]

The goal umpire signals a goal with two hands pointed forward at elbow height, or a behind with one hand. Both goal umpires then wave flags above their heads to communicate this information to the scorers. The team that has scored the most points at the end of play wins the game. If the scores are level on points at the end of play, then the game is a draw; extra time applies only during finals matches in some competitions.

As an example of a score report, consider a match between Essendon and Melbourne with the former as the home team. Essendon's score of 11 goals and 14 behinds equates to 80 points. Melbourne's score of 10 goals and 7 behinds equates to a 67-point tally. Essendon wins the match by a margin of 13 points. Such a result would be written as:

- "Essendon 11.14 (80) defeated Melbourne 10.7 (67)."[68]

And spoken as:

- "Essendon, eleven-fourteen, eighty, defeated Melbourne ten-seven, sixty-seven".

Additionally, it can be said that:

- "Essendon defeated Melbourne by thirteen points".

The home team is typically listed first and the visiting side is listed second. The scoreline is written with respect to the home side.

For example, Port Adelaide won in successive weeks, once as the home side and once as the visiting side. These would be written out thus:

- "Port Adelaide 23.20 (158) defeated Essendon 8.14 (62)."[69]

- "West Coast 17.13 (115) defeated by Port Adelaide 18.10 (118)."[70]

A draw would be written as:

- "Greater Western Sydney 10.8 (68) drew with Geelong 10.8 (68)".[71]

Structure and competitions[]

The football season proper is from March to August (early autumn to late winter in Australia) with finals being held in September and October.[72] In the tropics, the game is sometimes played in the wet season (October to March).[73]

The AFL is recognised by the Australian Sports Commission as being the National Sporting Organisation for Australian Football.[74] There are also seven state/territory-based organisations in Australia, all of which are affiliated with the AFL.[75] These state leagues hold annual semi-professional club competitions, with some also overseeing more than one league. Local semi-professional or amateur organisations and competitions are often affiliated to their state organisations.[76]

The AFL is the de facto world governing body for Australian football. There are also a number of affiliated organisations governing amateur clubs and competitions around the world.[77]

For almost all Australian football club competitions the aim is to win the Premiership. The premiership is typically decided by a finals series. The teams that occupy the highest positions on the ladder after the home-and-away season play off in a "semi-knockout" finals series, culminating in a single Grand Final match to determine the premiers. Between four and eight teams contest a finals series, typically using the AFL final eight system[78] or a variation of the McIntyre System.[79][80] The team which finishes first on the ladder after the home-and-away season is referred to as a "minor premier", but this usually holds little stand-alone significance, other than receiving a better draw in the finals.

Many metropolitan leagues have several tiered divisions, with promotion of the lower division premiers and relegation of the upper division's last placed team at the end of each year.[81] At present, none of the top level national or state level leagues in Australia utilise this structure.

Women and Australian football[]

The high level of interest shown by women in Australian football is considered unique among the world's football codes.[82] It was the case in the 19th century, as it is in modern times, that women made up approximately half of total attendances at Australian football matches—a far greater proportion than, for example, the estimated 10 per cent of women that comprise British soccer crowds.[83] This has been attributed in part to the egalitarian character of Australian football's early years in public parks where women could mingle freely and support the game in various ways.[84]

In terms of participation, there are occasional 19th-century references to women playing the sport, but it was not until the 1910s that the first organised women's teams and competitions appeared.[85] Women's state leagues emerged in the 1980s,[86] and in 2013, the AFL announced plans to establish a nationally televised women's competition.[87] Amidst a surge in viewing interest and participation in women's football, the AFL pushed the founding date of the competition, named AFL Women's, to 2017.[88] Eight AFL clubs won licences to field sides in its inaugural season.[89]

[]

Many related games have emerged from Australian football, mainly with variations of contact to encourage greater participation. These include Auskick (played by children aged between 5 and 12), kick-to-kick (and its variants end-to-end footy and marks up), rec footy, 9-a-side footy, masters Australian football, handball and longest-kick competitions. Players outside of Australia sometimes engage in related games adapted to available fields, like metro footy (played on gridiron fields) and Samoa rules (played on rugby fields). One such prominent example in use since 2018 is AFLX, a shortened variation of the game with seven players a side, played on a soccer-sized pitch.[90]

International rules football[]

The similarities between Australian football and the Irish sport of Gaelic football have allowed for the creation of a hybrid code known as international rules football. The first international rules matches were contested in Ireland during the 1967 Australian Football World Tour. Since then, various sets of compromise rules have been trialed, and in 1984 the International Rules Series commenced with national representative sides selected by Australia's state leagues (later by the AFL) and the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). The competition became an annual event in 1998, but was postponed indefinitely in 2007 when the GAA pulled out due to Australia's severe and aggressive style of play.[91] It resumed in Australia in 2008 under new rules to protect the player with the ball.

Global reach[]

Australian rules football is played throughout the world. 26 countries have participated in the International Cup (held trienially since 2002 and the highest level of international competition), and 20 countries have participated in the Euro Cup, both of which prohibit Australian players. Over 20 countries have either affiliation or working agreements with the AFL (which became the world governing body in when it dissolved the International Australian Football Council in 2002).[92] There have been many VFL/AFL players who were born outside Australia, an increasing number of which have been recruited through initiatives open to players from around the world (such as the AFL International Combine) and, more recently, international scholarship programs.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the game rapidly spread with the Australian diaspora to areas such as New Zealand (1871), England (1888),[93] South Africa (1898), Canada and the United States (1906), and Nauru (1919). From the 1880s touring sides were helping the major football codes spread throughout the world. With the increasing divergence of the football codes, early touring sides from England and New Zealand would have to switch codes or play under compromise rules to facilitate tests. Proposed touring Australian football teams faced the reverse dilemma. Post-Federation of the Australian colonies, the game's governing bodies were becoming highly insular in their approach. In particular, until the middle of the century, the game's premier leagues, the newly formed and increasingly professional VFL (and to a lesser extent the South Australian league), were preferential in the support they provided to overseas competitions to those areas perceived to pose the least potential threat to their status. They had become strongly opposed to the game's development in larger first world nations. Faced with the growth of British sports and their increasing professionalism in Australia and growing interest around the world in the Australian game the Australasian Football Council (and its major affiliates) implemented a domestic policy for game development in 1906. The council's policy reflected the strong Australian nationalism of the time "one flag, one destiny, one football game" - that all matches should be played under an Australian flag, with an Australian manufactured ball where possible on Australian soil, by the whole nation.[94] The council believed it could better defend its premier position in Australia by allocating all its promotional resources to grow its marketshare in New South Wales and Queensland whilst its coexistence with rugby and the promise of a universal football code was part of its ambition of keeping growth of the game in Australia under its national (and international) control. While it allowed voting member New Zealand to send a team to the 1908 Melbourne Carnival, the policy meant no touring sides and the phasing out of financial support which stymied the game outside Australia creating significant financial and logistic barriers for overseas sides to compete. The nationalistic policies were reinforced by the 1908 Prime Ministerial speech of former player Alfred Deakin delivered at the opening of the 1908 carnival[95] and would underpin the governing body's international policy for more than half a century.

Western Australia (where the code was outgrowing rugby without significant financial assistance) was highly critical of these policies and implemented its own strategies to help foster the game overseas and support its long term sustainability at home.[96] This included facilitating tours that, whilst not sanctioned by the game's governing body, led to the first international matches at junior level.[97] These included: United States vs Australia (San Francisco, 1911) and Canada vs United States (Vancouver, 1912).

Despite some progress the combined impact of World War I and the AFC's policies saw most competitions outside Australia (along with many domestically) go into deep recess by the 1920s and rugby become firmly established outside of its heartlands.[98] In the post-war era, however, the sport experienced an unexpected boom in the Pacific in the dependent territories of Papua New Guinea (1944) and Nauru where rugby had been introduced first, but Australian Rules had clearly become a major participation and spectator sport.[99]

Research primarily from Irish and English sources now strongly indicates that the Victorian Rules of 1866 and 1877[100][101] were used by the Gaelic Athletic Association in Ireland in 1887 to codify Gaelic football dispelling the long held myth of the sport having Irish origins.[102] Now the most popular sport in Ireland, it has remained similar to Australian Rules since and arguably more widespread as it was exported with the Irish Diaspora in the 1920s, a period in which Australian rules was mostly confined to Australia. The first interactions between the two countries codes began to occur during this period.[103] The idea of a hybrid code was later agreed upon to facilitate tests and became known as International rules football. Though the GAA has remained strictly amateur, Irish and Australian sides are typically fairly evenly matched in the hybrid code. In 1967, Australian Harry Beitzel organized the Australian Football World Tour including a team to travel to Ireland and play Mayo and All-Ireland senior champions Meath. Known as the Galahs, it included Bob Skilton, Royce Hart, Alex Jesaulenko and Ron Barassi as captain-coach. Many of the overseas-born AFL players have been Irish, as interest in recruiting talented Gaelic footballers dates back to the start of the Irish experiment. Among the more successful recruits were Brownlow Medalist Jim Stynes and premiership player Tadhg Kennelly. The International Rules Series was a popular series of tests in which the AFL and GAA selected teams to play International Rules matches against in alternating tours. Matches were often played at the most prestigious venues of the AFL and GAA – the MCG and Croke Park respectively. While the AFL and GAA All-Ireland no longer participate, International Rules is still used to facilitate matches between amateur leagues such as the Australian Amateur Football Council and GAAs around the world.

Australian rules experienced an international revival in the 1970s and 1980s. It is during this time that the first modern amateur clubs and competitions spread through Oceania including in New Zealand (1974), and to the other continents of: Asia (1987), Europe and North America (1989), South America and Africa (1997). The sport developed a cult following in the United States when matches were broadcast on the fledgling ESPN network in the 1980s.[104] As the size of the Australian diaspora has increased, so has the number of clubs outside Australia. This expansion has been further aided by multiculturalism and assisted by exhibition matches as well as exposure generated through players who have converted to and from other football codes. In Papua New Guinea, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, and the United States there are many thousands of players.

The first senior international test was played in 1976 between the national sides of Papua New Guinea and Nauru in front of a crowd of over 10,000 at Sir Hubert Murray Stadium in Port Moresby which PNG won by 129 points.[105] Papua New Guinea came within two goals of Australia in the first match between the two countries in 1978 at U17 level at Football Park in Adelaide.[106] An Australian Under 17 AFL Academy development side began playing international tests for national sports funding including matches against South Africa (2007)[107] and New Zealand (2012).[108] While New Zealand came within a goal in 2014, the Australian side remains unbeaten. Australia has also sent a touring junior indigenous sides which were defeated by Papua New Guinea (2009)[109] but won against both South Africa[110] and New Zealand (2013).[111] With the vast majority of international players still being amateurs, there are currently no plans for Australia to compete internationally at senior level.

A fan of the sport since attending school in Geelong, Prince Charles is the Patron of AFL Europe. In 2013, participation across AFL Europe's 21 member nations was more than 5,000 players, the majority of which are European nationals rather than Australian expats.[112] The sport also has a growing presence in India.[113]

Although Australian rules football has not yet been a full sport at the Olympic Games or Commonwealth Games, when Melbourne hosted the 1956 Summer Olympics, which included the MCG being the main stadium, Australian rules football was chosen as the native sport to be demonstrated as per International Olympic Committee rules. On 7 December, the sport was demonstrated as an exhibition match at the MCG between a team of VFL and VFA amateurs and a team of VAFA amateurs (professionals were excluded due to the Olympics' strict amateurism policy at the time). The Duke of Edinburgh was among the spectators for the match, which the VAFA won by 12.9 (81) to 8.7 (55). Australian rules was once again a demonstration sport at the 1982 Commonwealth Games in Brisbane.[114]

Cultural impact and popularity[]

Australian football is a sport rich in tradition and Australian cultural references, especially surrounding the rituals of gameday for players, officials and supporters.

Australian football has attracted more overall interest among Australians than any other football code,[115] and, when compared with all sports throughout the nation, has consistently ranked first in the winter reports, and third behind cricket and swimming in summer.[116] Over 875,000 fans were paying members of AFL clubs in 2016, which is equal to one in every 28 Australians.[117] The 2016 AFL Grand Final was the year's most-watched television broadcast in Australia, with an in-home audience of up to 6.5 million watching the match.[118][119]

In 2006, 615,549 registered participants played Australian football in Australia.[120] Participation increased 7.84% between 2005 and 2006.[120] The Australian Sports Commission statistics showed a 64% increase in the total number of participants over the 10-year period between 2001 and 2010.[121] In 2008 there were 35,000 people in 32 countries playing in structured competitions of Australian football outside of Australia.[122]

In the arts and popular culture[]

Australian football has been an inspiration for writers and poets including C. J. Dennis, Manning Clarke and Bruce Dawe.[123] Paintings by Arthur Streeton (The National Game, 1889) and Sidney Nolan (Footballer, 1946) helped to establish Australian football as a serious subject for artists.[124] Many Aboriginal artists have explored the game, often fusing it with the mythology of their region.[125][126] Statues of Australian football identities can be found throughout the country. In cartooning, WEG's VFL/AFL premiership posters—inaugurated in 1954—have achieved iconic status among Australian football fans.[127] Dance sequences based on Australian football feature heavily in Robert Helpmann's 1964 ballet The Display, his first and most famous work for the Australian Ballet.[128] The game has also inspired well-known plays such as And the Big Men Fly (1963) by Alan Hopgood and David Williamson's The Club (1977), which was adapted into a 1980 film, directed by Bruce Beresford. Mike Brady's 1979 hit "Up There Cazaly" is considered an Australian football anthem, and references to the sport can be found in works by popular musicians, from singer-songwriter Paul Kelly to the alternative rock band TISM.[129] Many Australian football video games have been released, most notably the AFL series.

Australian Football Hall of Fame[]

For the centenary of the VFL/AFL in 1996, the Australian Football Hall of Fame was established. That year, 136 significant figures across the various competitions were inducted into the Hall of Fame. An additional 115 inductees have been added since the creation of the Hall of Fame, resulting in a total number of 251 inductees.[130]

In addition to the Hall of Fame, select members are chosen to receive the elite Legend status. Due to restrictions limiting the number of Legend status players to 10% of the total number of Hall of Fame inductees, there are currently 25 players with the status in the Hall of Fame.[130]

See also[]

- ACL injuries in the Australian Football League

- Australian rules football attendance records

- Australian rules football positions

- List of Australian rules football clubs

- List of Australian rules football rivalries

- List of Australian rules football terms

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ a b Collins, Ben (22 November 2016). "Women's football explosion results in record participation" Archived 22 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, AFL. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "About the AFL: Australian Football (Official title of the code)". Australian Football League. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ 2012 Laws of the game Archived 22 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine Section 14, page 45

- ^ History Archived 13 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine Official Website of the Australian Football League

- ^ Wendy Lewis, Simon Balderstone and John Bowan (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Kwek, Glenda (26 March 2013). "AFL leaves other codes in the dust" Archived 6 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ "AFL is clearly Australia’s most watched Football Code, while V8 Supercars have the local edge over Formula 1" Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine (14 March 2014), Roy Morgan. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ^ "The richest codes in world sport: Forget the medals, these sports are chasing the gold" (8 May 2014). Courier Mail. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ "History website". Footy.com.au. Archived from the original on 19 February 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ Connolly, Rohan (22 March 2012). "Name of the game is up in the air in NSW". The Age. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ First Australian Rules Game Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Monument Australia. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ Hess 2008, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Pennings 2012, p. 8.

- ^ Pennings 2012, pp. 13–14.

- ^ de Moore 2011, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Blainey 2010, pp. 19–22.

- ^ Pennings 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Blainey 2010, pp. 23–26.

- ^ Ken Piesse (1995). The Complete Guide to Australian Football. Pan Macmillan Australia. p. 303. ISBN 0-330-35712-3.

- ^ Paproth, Daniel (4 June 2012). "The oldest of school rivals". The Weekly Review Stonnington. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ Collins, Tony (2011). "Chapter 1: National Myths, Imperial Pasts and the Origins of Australian Rules Football". In Wagg, Stephen (ed.). Myths and Milestones in the History of Sport. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-230-24125-1.

- ^ Blainey 2010, pp. 187–196.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 8.

- ^ de Moore 2011, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Pennings 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Pennings 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Coventry 2015, p. 2.

- ^ Pennings 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 7.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Pennings 2012, p. 25.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Coventry 2015, pp. 16–17, 20.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2009, p. 9.

- ^ de Moore 2011, pp. 87, 288–289.

- ^ a b Hess 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Pill, Shane; Frost, Lionel (17 January 2016). "R.E.N. Twopeny and the Establishment of Australian Football in Adelaide". The International Journal of the History of Sport. 33 (8): 797–812. doi:10.1080/09523367.2016.1173033. S2CID 147807924.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2010, pp. 22–24.

- ^ a b Hibbins & Ruddell 2010, p. 24.

- ^ Hibbins & Ruddell 2010, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Blainey 2010, pp. 107–108.

- ^ a b Pennings 2013.

- ^ Pramberg, Bernie (15 June 2015). "Love of the Game: Aussie rules a dominant sport in early Queensland", The Courier-Mail. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Healy, Matthew (2002). Hard Sell: Australian Football in Sydney Archived 18 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Melbourne, Vic.: Victoria University. pp. 20–28.

- ^ Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 351.

- ^ Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 351–352.

- ^ "Football in Australia". Evening Post, Volume LXXXVIII, Issue 122. New Zealand. 19 November 1914. p. 8. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- ^ "Football amalgamation". Evening Post, Volume LXXXIX, Issue 27. New Zealand. 2 February 1915. p. 8. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- ^ "A False Dawn". AustralianFootball.com. 20 August 1908. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ Marshall, Konrad (26 February 2016). "Where do rugby codes' strongholds turn to rules? At the 'Barassi Line', of course..." Archived 14 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Referenced in Hutchinson, Garrie (1983). The Great Australian Book of Football Stories. Melbourne: Currey O'Neil.

- ^ WICKS, B. M. Whatever Happened to Australian Rules? Hobart, Tasmania, Libra Books. 1980, First Edition. (ISBN 0-909619-06-9)

- ^ a b Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 342.

- ^ Nauright & Parrish 2012, p. 341.

- ^ Big names locked in for AFLW state of origin Archived 28 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. AFL News, 25 July 2017

- ^ "'We need to work together': Tasmanians need united front for AFL team, researcher says" Archived 3 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine (21 August 2015), ABC News. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ "Tasmania's AFL bid" Archived 3 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine (13 December 2008), AM, ABC Radio. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ Cherny, Daniel; Wilson, Caroline (31 May 2016). "AFL 2016: St Kilda want two 2018 games in Auckland" Archived 23 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Age. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ "Port Adelaide, Gold Coast Suns take AFL to China in 2017 regular season" Archived 1 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine (26 October 2016), ABC News. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ "15.7 Free Kicks – Relating to Out of Bounds". Laws of Australian Football 2017 (PDF). Australian Football League. 2017. p. 51. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ "AFL rules on deliberate rushed behinds". Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "All clear for rushed behind rule". Herald Sun.

- ^ "Essendon v Melbourne". AFL Tables. 2 April 2016. Archived from the original on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "AFL Match Statistics : Port Adelaide defeats Essendon at AAMI Stadium Round 1 Sunday, 28th March 2004". www.footywire.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "AFL Match Statistics : West Coast defeated by Port Adelaide at Domain Stadium Round 2 Saturday, 3rd April 2004". www.footywire.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ "Greater Western Sydney v Geelong". AFL Tables. 1 July 2017. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "Schedule – By Round" (PDF). 20 March 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2007.

- ^ Finlayson, Sean (30 November 2006). "Bombers soaring on the Tiwi Islands". World Footy News. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ "Australian Institute of Sport – Australian football". Australian Institute of Sport. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ "Inquiry into Country Football" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "LEAGUES & ASSOCIATIONS". AFL Victoria. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ "International – Official Website of the Australian Football League". Australian Football League. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ "Australian Football League Regulations" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "Adelaide Footy League - Rules & Regulations". Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "EXPLAINING THE FINAL SIX". VAFA. 22 July 2013. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "Rules of the Victorian Amateur Football Association" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Mewett & Toffoletti 2008, p. 2.

- ^ Hess 2008, p. 66.

- ^ Browne, Ashley (2008). "For Women, Too". In Weston, James. The Australian Game of Football: Since 1858. Geoff Slattery Publishing. pp. 253–259. ISBN 978-0-9803466-6-4.

- ^ Hess & Lenkic 2016, pp. 1–6.

- ^ Pippos 2017, p. 191.

- ^ Lane, Samantha (27 March 2013). "AFL sees the light on women's footy" Archived 23 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Age. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Halloran, Jessica (29 January 2017). "Will the AFL Women’s League level the playing field?" Archived 24 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ Mark, David (17 June 2016). "AFL women's competition provides a pathway for young women into professional sport" Archived 1 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, ABC. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ "AFLX revealed: Who your club plays". AFL.com.au. 17 November 2017. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ Haxton, Nance (3 January 2007). "Sounds of Summer: International Rules Series" Archived 31 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine. PM, ABC Radio National. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ AFL International Development Archived 21 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Williamson 2003, pp. 138–140.

- ^ David Goldblatt (30 August 2007). The Ball is Round: A Global History of Football. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-191154-0. OCLC 1004977972.

- ^ Judd, Barry; Hallinan, Christopher (1 December 2019). "Indigeneity and the Disruption of Anglo-Australian Nationalism in Australian Football". Review of Nationalities. 9 (1): 101–110. doi:10.2478/pn-2019-0008. eISSN 2543-9391.

- ^ "Young Australia League". . 2 (60). Western Australia. 9 June 1906. p. 4. Retrieved 7 October 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Australian Game of Football Is Best – So Says Major Peixotto, the Pacific Coast Amateur Athletic Union Leader" (PDF). The New York Times. 23 October 1910. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ Wicks, B. M. (1980). Whatever happened to Australian Rules. Hobart: Libra Books. ISBN 978-0-909619-06-0. OCLC 27582183.

- ^ Roffey, Chelsea (30 July 2008). "Team Profile: Nauru Chiefs". Afl.com.au. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ "Towards a Philosophy for Legislation in Gaelic Games. Lennon, Joe. Dublin City University 1993. Pg 633, 638, 649, 658, 759

- ^ Collins, Tony. How Football Began: A Global History of How the World's Football Codes Were Born. New York: Routledge, 2019.

- ^ Did Aussie Rules Get There First? from Irish Daily Mail 25 October 2016

- ^ "AUSTRALIAN AND GAELIC CODES". The Australasian. CXXI (4, 048). Victoria, Australia. 31 July 1926. p. 41 (METROPOLITAN EDITION). Retrieved 1 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Delaney, Tim; Madigan, Tim (2009). The Sociology of Sports: An Introduction. McFarland. pp. 284–285. ISBN 978-0786453153.

- ^ It’s PNG by 129 points. PNG Post Courier. 21 Sep 1976 Page 24

- ^ "AUSSIES OUT DO PNG". Papua New Guinea Post-courier. International, Australia. 8 June 1978. p. 26. Retrieved 3 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Aussie U17s crush South Africa from AFL.com.au

- ^ New Zealand Hawks v AIS AFL Academy 2013

- ^ Boomerangs take game to PNG

- ^ Flying Boomerangs tour in South Africa from SBS

- ^ Flying Boomerangs star in New Zealand December 17, 2013

- ^ "The Prince of Wales becomes Patron of AFL Europe". princeofwales.gov.uk. 25 October 2013. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Rith Basu, Ayan Paul (2 November 2015). "Soccer city gets a taste of Aussie football". Archived from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ AFL's chance to take on rugby at Brisbane Olympics 30 July 2021

- ^ "Sweeney Sport report for 2006–07" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Derriman, Philip (22 May 2003). "If you can kick it, Australia will watch it". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2005.

- ^ Bowen, Nick (25 August 2016). "The membership ladder: Hawks overtake Pies, Dons slide" Archived 22 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. AFL. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ Hickman, Arvind (29 November 2016). "AdNews analysis: The top 50 TV programs of 2016" Archived 4 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, AdNews. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ Styles, Aja (2 October 2016). "AFL Grand Final 2016 has highest footy ratings for Channel 7 in a decade" Archived 24 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ a b Niall, Jake (20 June 2007). "More chase Sherrin than before". Real Footy. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ "Participation in Exercise, Recreation and Sport Survey 2010 Annual Report" (PDF). pp. 34–35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2011.

- ^ Curtis, R. (11 May 2008). "Pacific nations bemoan AFL neglect". The Sunday Age (Melbourne).

- ^ Alomes, Stephen (2007), "The Lie of the Ground: Aesthetics and Australian Football", Double Dialogues, Deakin University (8), ISSN 1447-9591, archived from the original on 2 June 2015

- ^ McAullife, Chris (1995). "Eyes on the Ball: Images of Australian Rules Football", Art & Australia (Vol 32 No 4), pp. 490–500

- ^ Heathcote, Christopher (August 2009). "Bush Football: The Kunoth Family", Art Monthly (Issue 222).

- ^ Angel, Anita (23 November 2009). "Looking at Art" Archived 23 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Charles Darwin University Art Collection & Art Gallery. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ Rielly, Stephen (30 December 2008). "Cartoonist William Ellis Green spoke to AFL tribe", The Australian. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Douglas, Tim (30 August 2012). "Ballet's former glories show footy's left its mark" Archived 21 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Australian. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ Worrell, Shane (3 April 2010). "Modern footy not in tune" Archived 24 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Bendigo Advertiser. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ a b "About the AFL Hall of Fame". afl.com.au. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

Sources[]

Books[]

- Blainey, Geoffrey (2010). A Game of Our Own: The Origins of Australian Football. Black Inc. ISBN 9781863954853.

- Coventry, James (2015). Time and Space: The Tactics That Shaped Australian Rules and the Players and Coaches Who Mastered Them. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-7333-3369-9.

- de Moore, Greg (2011). Tom Wills: First Wild Man of Australian Sport. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74237-598-4.

- Hess, Rob (2008). A National Game: The History of Australian Rules Football. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-07089-3.

- Hess, Rob; Lenkic, Brunette (2016). Play On! The Hidden History of Women's Australian Rules Football. Bonnier Zaffre. ISBN 9781760063160.

- Hibbins, Gillian; Mancini, Anne (1987). Running with the Ball: Football's Foster Father. Lynedoch Publications. ISBN 978-0-7316-0481-4.

- Hibbins, Gillian (2008). "Men of Purpose". In Weston, James (ed.). The Australian Game of Football: Since 1858. Geoff Slattery Publishing. pp. 31–45. ISBN 978-0-9803466-6-4.

- Hibbins, Gillian (2013). "The Cambridge Connection: The English Origins of Australian Football". In Mangan, J. A. (ed.). The Cultural Bond: Sport, Empire, Society. Routledge. pp. 108–127. ISBN 9781135024376.

- Nauright, John; Parrish, Charles (2012). Sports Around the World: History, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598843002.

- Pennings, Mark (2012). Origins of Australian Football: Victoria's Early History: Volume 1: Amateur Heroes and the Rise of Clubs, 1858 to 1876. Connor Court Publishing Pty Ltd. ISBN 9781921421471.

- Pippos, Angela (2017). Breaking the Mould. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781925475296.

- Williamson, John (2003). Bucknell, Mar (ed.). Football's Forgotten Tour: The Story of the British Australian Rules Venture of 1888. Applegate. ISBN 9780958101806.

Journal and conference articles[]

- Hibbins, Gillian; Ruddell, Trevor (2009). ""A Code of Our Own": Celebrating 150 Years of the Rules of Australian Football" (PDF). The Yorker (39). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- Hibbins, Gillian; Ruddell, Trevor (2010). "The Evolution of the Rules of Football From 1872 to 1877" (PDF). The Yorker (41). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- Mewett, Peter; Toffoletti, Kim (2008). The Strength of Strong Ties: How Women Become Supporters of Australian Rules Football. Australian Sociological Association Conference. University of Melbourne. ISBN 9780734039842.

- Pennings, Mark (2013). "Fuschias, Pivots, Same Olds and Gorillas: The Early Years of Football in Victoria" (PDF). Tablet to Scoreboard. 1 (1). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Australian rules football. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Australian Rules Football. |

- Australian Football League (AFL) official website

- Australian Football: Celebrating The History of the Great Australian Game

- 2020 Laws of Australian Football

- Australian Football explained in 31 languages – a publication from AFL.com.au

- Reading Australian Rules Football - The Definitive Guide to the Game

- State Library of Victoria Research Guide to Australian Football

- Australian rules football

- 1858 introductions

- 1859 establishments in Australia

- Ball games

- Football codes

- Sports originating in Australia

- Team sports