Axis naval activity in Australian waters

Although Australia was remote from the main battlefronts, there was considerable Axis naval activity in Australian waters during the Second World War. A total of 54 German and Japanese warships and submarines entered Australian waters between 1940 and 1945 and attacked ships, ports and other targets. Among the best-known attacks are the sinking of HMAS Sydney by a German raider in November 1941, the bombing of Darwin by Japanese naval aircraft in February 1942, and the Japanese midget submarine attack on Sydney Harbour in May 1942. In addition, many Allied merchant ships were damaged or sunk off the Australian coast by submarines and mines. Japanese submarines also shelled several Australian ports and submarine-based aircraft flew over several Australian capital cities.

The Axis threat to Australia developed gradually and until 1942 was limited to sporadic attacks by German armed merchantmen. The level of Axis naval activity peaked in the first half of 1942 when Japanese submarines conducted anti-shipping patrols off Australia's coast, and Japanese naval aviation attacked several towns in northern Australia. The Japanese submarine offensive against Australia was renewed in the first half of 1943 but was broken off as the Allies pushed the Japanese onto the defensive. Few Axis naval vessels operated in Australian waters in 1944 and 1945, and those that did had only a limited impact.

Due to the episodic nature of the Axis attacks and the relatively small number of ships and submarines committed, Germany and Japan were not successful in disrupting Australian shipping. While the Allies were forced to deploy substantial assets to defend shipping in Australian waters, this did not have a significant impact on the Australian war effort or American-led operations in the South West Pacific Area.

Australia Station and Australian defences[]

The definition of "Australian waters" used throughout this article is, broadly speaking, the area which was designated the Australia Station prior to the outbreak of war. This vast area consisted of the waters around Australia and eastern New Guinea, and stretching south to Antarctica. From east to west, it stretched from 170° east in the Pacific Ocean to 80° east in the Indian Ocean, and from north to south it stretched from the Equator to the Antarctic.[1] While the eastern half of New Guinea was an Australian colonial possession during the Second World War and fell within the Australia Station, the Japanese operations in these waters formed part of the New Guinea and Solomon Islands Campaigns and were not directed at Australia.

The defence of the Australia Station was the Royal Australian Navy's main concern throughout the war.[2] While RAN ships frequently served outside Australian waters, escort vessels and minesweepers were available to protect shipping in the Australia Station at all times. These escorts were supported by a small number of larger warships, such as cruisers and armed merchant cruisers, for protection against surface raiders.[3] While important military shipping movements were escorted from the start of the war, convoys were not instituted in Australian waters until June 1942. The Australian naval authorities did, however, close ports to shipping at various times following real or suspected sightings of enemy warships or mines prior to June 1942.

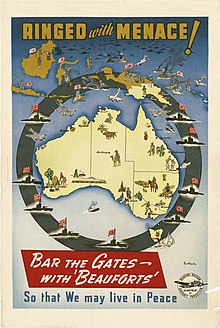

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) was also responsible for the protection of shipping within the Australia Station.[4] Throughout the war, RAAF aircraft escorted convoys and conducted reconnaissance and anti-submarine patrols from bases around Australia. The main types of aircraft used for maritime patrol were Avro Ansons, Bristol Beauforts, Consolidated PBY Catalinas and Lockheed Hudsons. Following the outbreak of the Pacific War, RAAF fighter squadrons were also stationed to protect key Australian ports and escorted shipping in areas where air attack was feared.

The Allied naval forces assigned to the Australia Station were considerably increased following Japan's entry into the war and the beginning of the United States military build-up in Australia. These naval forces were supported by a large increase in the RAAF's maritime patrol force and the arrival of United States Navy patrol aircraft. Following the initial Japanese submarine attacks, a convoy system was instituted between Australian ports, and by the end of the war the RAAF and RAN had escorted over 1,100 convoys along the Australian coastline.[5] As the battlefront moved to the north and attacks in Australian waters became less frequent, the number of ships and aircraft assigned to shipping protection duties within the Australia Station was considerably reduced.[6]

In addition to the air and naval forces assigned to protect shipping in Australian waters, fixed defences were constructed to protect the major Australian ports. The Australian Army was responsible for developing and manning coastal defences to protect ports from attacks by enemy surface raiders. These defences commonly consisted of a number of fixed guns defended by anti-aircraft guns and infantry.[7] The Army's coastal defences were considerably expanded as the threat to Australia increased between 1940 and 1942, and reached their peak strength in 1944.[8] The Royal Australian Navy was responsible for developing and manning harbour defences in Australia's main ports.[9] These defences consisted of fixed anti-submarine booms and mines supported by small patrol craft, and were also greatly expanded as the threat to Australia increased.[10] The RAN also laid defensive minefields in Australian waters from August 1941.[11]

While the naval and air forces available for the protection of shipping in Australian waters were never adequate to defeat a heavy or coordinated attack, they proved sufficient to mount defensive patrols against the sporadic and generally cautious attacks mounted by the Axis navies during the war.[12]

1939–1941[]

German surface raiders in 1940[]

While German surface raiders operated in the western Indian Ocean in 1939 and early 1940, they did not enter Australian waters until the second half of 1940. The first Axis ships in Australian waters were the unarmed Italian ocean liners Remo and Romolo, which were in Australian waters when Fascist Italy entered the war on 11 June 1940, Eastern Australian Time. While Remo was docked at Fremantle and was easily captured, Romolo proved harder to catch, as she had left Brisbane on 5 June bound for Italy. Following an air and sea search, Romolo was intercepted by HMAS Manoora near Nauru on 12 June and was scuttled by her captain to avoid capture.[13]

The German surface raider Orion was the first Axis warship to operate in Australian waters during World War II. After operating off the northern tip of New Zealand and the South Pacific, Orion entered Australian waters in the Coral Sea in August 1940 and closed to within 120 nmi (140 mi; 220 km) north-east of Brisbane on 11 August.[14] Following this, Orion headed east and operated off New Caledonia before proceeding south into the Tasman Sea, sinking the merchant ship Notou south-west of Noumea on 16 August and the British merchant ship Turakina in the Tasman Sea four days later. Orion sailed south-west after sinking Turakina, passing south of Tasmania, and operated without success in the Great Australian Bight in early September. While Orion laid four dummy mines off Albany, Western Australia on 2 September, she departed to the south-west after being spotted by an Australian aircraft the next day. After unsuccessfully patrolling in the Southern Ocean, Orion sailed for the Marshall Islands to refuel, arriving there on 10 October.[15]

Pinguin was the next raider to enter Australian waters. Pinguin entered the Indian Ocean from the South Atlantic in August 1940 and arrived off Western Australia in October. Pinguin captured the 8,998 long tons (9,142 t) Norwegian tanker Storstad[16] off North West Cape on 7 October and proceeded east with the captured ship. Pinguin laid mines between Sydney and Newcastle on 28 October, and Storstad laid mines off the Victorian coast on the nights of 29–31 October. Pinguin also laid further mines off Adelaide in early November. The two ships then sailed west for the Indian Ocean. Pinguin and Storstad were not detected during their operations off Australia's eastern and southern coasts, and succeeded in sinking three ships. Mines laid by Storstad sank two ships (Cambridge and City of Rayville) off Wilsons Promontory in early November, and the mines laid off Sydney by Pinguin sank one ship (Nimbin) and a further merchant ship (Herford) was damaged after striking a mine off Adelaide. Pinguin added to her tally of successes in Australian waters by sinking three merchant ships in the Indian Ocean during November.[17]

On 7 December 1940, the German raiders Orion and Komet arrived off the Australian protectorate of Nauru. During the next 48 hours, the two ships sank four merchant ships off the undefended island.[18] Heavily loaded with survivors from their victims, the raiders departed for Emirau Island where they unloaded their prisoners. After an unsuccessful attempt to lay mines off Rabaul on 24 December, Komet made a second attack on Nauru on 27 December and shelled the island's phosphate plant and dock facilities.[19] This attack was the last Axis naval attack in Australian waters until November 1941.[20]

Consequences of the raid on Nauru led to serious concern about the supply of phosphates from there and nearby Ocean Island, though the general situation with naval forces allowed only limited response to threats to the isolated islands.[21] There was some redeployment of warships and a proposal to deploy six inch naval guns to the islands despite provisions of the mandate prohibiting fortification but a shortage of such guns resulted in a change to a proposed two field guns for each island.[22] The most serious effect of the raid was the fall in phosphate output in 1941 though decisions as early as 1938 to increase stockpiles of raw rock in Australia mitigated that decline.[23] Another consequence was the institution of the first Trans-Tasman commercial convoys with Convoy VK.1 composed of Empire Star, , Empress of Russia, and Maunganui leaving Sydney 30 December 1940 for Auckland escorted by HMNZS Achilles.[22]

German surface raiders in 1941[]

Following the raids on Nauru, Komet and Orion sailed for the Indian Ocean, passing through the Southern Ocean well to the south of Australia in February and March 1941 respectively. Komet re-entered the Australia station in April en route to New Zealand, and Atlantis sailed east through the southern extreme of the Australia Station in August.[24] Until November, the only casualties from Axis ships on the Australia Station were caused by mines laid by Pinguin in 1940. The small trawler Millimumul was sunk with the loss of seven lives after striking a mine off the New South Wales coast on 26 March 1941, and two ratings from a Rendering Mines Safe party were killed while attempting to defuse a mine which had washed ashore in South Australia on 14 July.[20]

On 19 November 1941, the Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney—which had been highly successful in the Battle of the Mediterranean—encountered the disguised German raider Kormoran, approximately 150 mi (130 nmi; 240 km) south west of Carnarvon, Western Australia. Sydney intercepted Kormoran and demanded that she prove her assumed identity as the Dutch freighter Straat Malakka. During the interception, Sydney's captain brought his ship dangerously close to Kormoran. As a result, when Kormoran was unable to prove her identity and avoid a battle she had little hope of surviving, the raider was able to use all her weaponry against Sydney. In the resulting battle, Kormoran and Sydney were both crippled, with Sydney sinking with the loss of all her 645 crew and 78 of Kormoran's crew being either killed in the battle or dying before they could be rescued by passing ships.[25]

Kormoran was the only Axis ship to conduct attacks in Australian waters during 1941 and the last Axis surface raider to enter Australian waters until 1943. There is no evidence to support claims that a Japanese submarine participated in the sinking of HMAS Sydney.[26] The only German ship to enter the Australia Station during 1942 was the blockade runner and supply ship Ramses, which was sunk by HMAS Adelaide and HNLMS Jacob van Heemskerk on 26 November, shortly after Ramses left Batavia bound for France. All of Ramses' crew survived the sinking and were taken prisoner.[27]

1942[]

The naval threat to Australia increased dramatically following the outbreak of war in the Pacific. During the first half of 1942, the Japanese mounted a sustained campaign in Australian waters, with Japanese submarines attacking shipping and aircraft carriers conducting a devastating attack on the strategic port of Darwin. In response to these attacks the Allies increased the resources allocated to protecting shipping in Australian waters.[28]

Early Japanese submarine patrols (January–March 1942)[]

The first Japanese submarines to enter Australian waters were I-121, I-122, I-123 and I-124, from the Imperial Japanese Navy's (IJN's) Submarine Squadron 6. Acting in support of the Japanese offensive in the Netherlands East Indies these boats laid minefields in the approaches to Darwin and the Torres Strait between 12 and 18 January 1942. These mines did not sink or damage any Allied ships.[29]

After completing their mine laying missions the four Japanese boats took station off Darwin to provide the Japanese fleet with warning of Allied naval movements. On 20 January 1942 the Australian Bathurst-class corvettes HMAS Deloraine, Katoomba and Lithgow sank I-124 near Darwin. This was the only full-sized submarine sunk by the Royal Australian Navy in Australian waters during World War II.[30] Being the first accessible ocean-going IJN submarine lost after Pearl Harbor, USN divers attempted to enter I-124 in order to obtain its code books, but were unsuccessful.[31]

Following the conquest of the western Pacific the Japanese mounted a number of reconnaissance patrols into Australian waters. Three submarines (I-1, I-2 and I-3) operated off Western Australia in March 1942, sinking the merchant ships Parigi and Siantar on 1 and 3 March respectively. In addition, I-25 conducted a reconnaissance patrol down the Australian east coast in February and March. During this patrol Nobuo Fujita from the I-25 flew a Yokosuka E14Y1 floatplane over Sydney (17 February), Melbourne (26 February) and Hobart (1 March).[32] Following these reconnaissances, I-25 sailed for New Zealand and conducted overflights of Wellington and Auckland on 8 and 13 March respectively.[33]

[]

The bombing of Darwin on 19 February 1942, was the heaviest single attack mounted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against mainland Australia. On 19 February, four Japanese aircraft carriers (Akagi, Kaga, Hiryū and Sōryū) launched a total of 188 aircraft from a position in the Timor Sea. The four carriers were escorted by four cruisers and nine destroyers.[34] These 188 naval aircraft inflicted heavy damage on Darwin and sank nine ships. A raid conducted by 54 land-based bombers later the same day resulted in further damage to the town and RAAF Base Darwin and the destruction of 20 Allied military aircraft. Allied casualties were 236 killed and between 300 and 400 wounded, the majority of whom were non-Australian Allied sailors. Only four Japanese aircraft were confirmed to have been destroyed by Darwin's defenders.[35]

The bombing of Darwin was the first of many Japanese naval aviation attacks against targets in Australia. The carriers Shōhō, Shōkaku and Zuikaku—which escorted the invasion force dispatched against Port Moresby in May 1942—had the secondary role of attacking Allied bases in northern Queensland once Port Moresby was secured.[36] These attacks did not occur, however, as the landings at Port Moresby were cancelled when the Japanese carrier force was mauled in the Battle of the Coral Sea.

Japanese aircraft made almost 100 raids, most of them small, against northern Australia during 1942 and 1943. Land-based IJN aircraft took part in many of the 63 raids on Darwin which took place after the initial attack. The town of Broome, Western Australia experienced a devastating attack by IJN fighter planes on 3 March 1942, in which at least 88 people were killed. Long-range seaplanes operating from bases in the Solomon Islands made a number of small attacks on towns in Queensland.[37]

Japanese naval aircraft operating from land bases also harassed coastal shipping in Australia's northern waters during 1942 and 1943. On 15 December 1942, four sailors were killed when the merchant ship Period was attacked off . The small general purpose vessel HMAS Patricia Cam was sunk by a Japanese floatplane near the Wessel Islands on 22 January 1943 with the loss of nine sailors and civilians. Another civilian sailor was killed when the merchant ship Islander was attacked by a floatplane during May 1943.[38]

Attacks on Sydney and Newcastle (May–June 1942)[]

In March 1942, the Japanese military adopted a strategy of isolating Australia from the United States by capturing Port Moresby in New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Fiji, Samoa and New Caledonia.[39] This plan was frustrated by the Japanese defeat in the Battle of the Coral Sea and was postponed indefinitely after the Battle of Midway.[40] Following the defeat of the Japanese surface fleet, the IJN submarines were deployed to disrupt Allied supply lines by attacking shipping off the Australian east coast.

On 27 April 1942, the submarines I-21 and I-29 left the major Japanese naval base at Truk Lagoon in the Japanese territory of the Caroline Islands to conduct reconnaissance patrols of Allied ports in the South Pacific. The goal of these patrols was to find a suitable target for the force of midget submarines, designated the Eastern Detachment of the Second Special Attack Flotilla, which was available in the Pacific.[41] I-29 entered Australian waters in May and made an unsuccessful attack on the neutral Soviet freighter Wellen off Newcastle on 16 May. I-29's floatplane overflew Sydney on 23 May 1942, finding a large number of major Allied warships in Sydney Harbour.[42] I-21 reconnoitred Suva, Fiji and Auckland, New Zealand in late May but did not find worthwhile concentrations of shipping in either port.[43]

On 18 May, the Eastern Detachment of the Second Special Attack Flotilla left Truk Lagoon under the command of Captain Hankyu Sasaki. Sasaki's force comprised I-22, I-24 and I-27. Each submarine was carrying a midget submarine.[44] After the intelligence gathered by I-21 and I-29 was assessed, the three submarines were ordered on 24 May to attack Sydney.[45] The three submarines of the Eastern Detachment rendezvoused with I-21 and I-29 35 mi (30 nmi; 56 km) off Sydney on 29 May.[46] In the early hours of 30 May, I-21's floatplane conducted a reconnaissance flight over Sydney Harbour that confirmed the concentration of Allied shipping sighted by I-29's floatplane was still present and was a worthwhile target for a midget submarine raid.[47]

On the night of 31 May, three midget submarines were launched from the Japanese force outside the Sydney Heads. Although two of the submarines (Midget No. 22 and Midget A, also known as Midget 24) successfully penetrated the incomplete Sydney Harbour defences, only Midget A actually attacked Allied shipping in the harbour, firing two torpedoes at the American heavy cruiser USS Chicago. These torpedoes missed Chicago but sank the depot ship HMAS Kuttabul, killing 21 seamen on board, and seriously damaged the Dutch submarine K IX. All of the Japanese midget submarines were lost during this operation (Midget No. 22 and Midget No. 27 were destroyed by the Australian defenders and Midget A was scuttled by her crew after leaving the Harbour).[48]

Following this raid, the Japanese submarine force operated off Sydney and Newcastle, sinking the coaster Iron Chieftain off Sydney on 3 June. On the night of 8 June, I-24 conducted a bombardment of the eastern suburbs of Sydney and I-21 bombarded Newcastle. Fort Scratchley at Newcastle returned fire, but did not hit I-21. While these bombardments did not cause any casualties or serious damage, they generated concern over further attacks against the east coast.[49] Following the attacks on shipping in the Sydney region, the Royal Australian Navy instituted convoys between Brisbane and Adelaide. All ships of over 1,200 long tons (1,200 t) and with speeds of less than 12 kn (14 mph; 22 km/h) were required to sail in convoy when travelling between cities on the east coast.[49] The Japanese submarine force left Australian waters in late June 1942 having sunk a further two merchant ships.[50] The small number of sinkings achieved by the five Japanese submarines sent against the Australian east coast in May and June did not justify the commitment of so many submarines.[51]

Further Japanese submarine patrols (July–August 1942)[]

The Australian authorities enjoyed only a brief break in the submarine threat. In July 1942, three submarines (I-11, I-174 and I-175) from Japanese Submarine Squadron 3 commenced operations off the East Coast. These three submarines sank five ships (including the small fishing trawler Dureenbee) and damaged several others during July and August. In addition, I-32 conducted a patrol off the southern coast of Australia while en route from New Caledonia to Penang, though the submarine was not successful in sinking any ships in this area. Following the withdrawal of this force in August, no further submarine attacks were mounted against Australia until January 1943.[52]

While Japanese submarines sank 17 ships in Australian waters in 1942 (14 of which were near the Australian coast) the submarine offensive did not have a serious impact on the Allied war effort in the South West Pacific or the Australian economy. Nevertheless, by forcing ships sailing along the east coast to travel in convoy the Japanese submarines were successful in reducing the efficiency of Australian coastal shipping. This lower efficiency translated into between 7.5% and 22% less tonnage being transported between Australian ports each month (no accurate figures are available and the estimated figure varied between months).[53] These convoys were effective, however, with no ship travelling as part of a convoy being sunk in Australian waters during 1942.[54]

1943[]

East coast submarine patrols (January–June 1943)[]

Japanese submarine operations against Australia in 1943 began when I-10 and I-21 sailed from Rabaul on 7 January to reconnoitre Allied forces around Nouméa and Sydney respectively. I-21 arrived off the coast of New South Wales just over a week later. I-21 operated off the east coast until late February and sank six ships during this period, making it the most successful submarine patrol conducted in Australian waters during the Second World War.[55] In addition to these sinkings, I-21's floatplane conducted a successful reconnaissance of Sydney Harbour on 19 February 1943.[56]

In March, I-6 and I-26 entered Australian waters. While I-6 laid nine German-supplied acoustic mines in the approaches to Brisbane this minefield was discovered by HMAS Swan and neutralised before any ships were sunk.[57] Although I-6 returned to Rabaul after laying her mines, the Japanese submarine force in Australian waters was expanded in April when the four submarines of Submarine Squadron 3 (I-11, I-177, I-178 and I-180) arrived off the east coast and joined I-26. This force had the goal of attacking reinforcement and supply convoys travelling between Australia and New Guinea.[58]

As the Japanese force was too small to cut off all traffic between Australia and New Guinea, the Squadron commander widely dispersed his submarines between the Torres Strait and Wilson's Promontory with the goal of tying down as many Allied ships and aircraft as possible. This offensive continued until June and the five Japanese submarines sank nine ships and damaged several others.[59] In contrast to 1942, five of the ships sunk off the Australian east coast were travelling in escorted convoys at the time they were attacked. The convoy escorts were not successful in detecting any submarines before they launched their attacks or counter-attacking these submarines.[60] The last attack by a Japanese submarine off the east coast of Australia was made by I-174 on 16 June 1943 when she sank the merchant ship Portmar and damaged U.S. Landing Ship Tank LST-469 as they were travelling in Convoy GP55 off the New South Wales north coast.[61] Some historians believe that RAAF aircraft searching for I-174 may have sunk I-178 during the early hours of 18 June, but the cause of this submarine's loss during a patrol off eastern Australia has not been confirmed.[62][63]

The single greatest loss of life resulting from a submarine attack in Australian waters occurred in the early hours of 14 May 1943 when I-177 torpedoed and sank the Australian hospital ship Centaur off Point Lookout, Queensland. After being hit by a single torpedo, Centaur sank in less than three minutes with the loss of 268 lives. While hospital ships—such as Centaur—were legally protected against attack under the terms of the Geneva Conventions, it is unclear whether Commander Hajime Nakagawa of I-177 was aware that Centaur was a hospital ship. While she was clearly marked with a red cross and was fully illuminated, the light conditions at the time may have resulted in Nakagawa not being aware of Centaur's status, making her sinking a tragic accident. However, as Nakagawa had a poor record as a submarine captain and was later convicted of machine gunning the survivors of a British merchant ship in the Indian Ocean, it is probable that the sinking of Centaur was due to either Nakagawa's incompetence or indifference to the laws of warfare.[64] The attack on Centaur sparked widespread public outrage in Australia.[65]

The Japanese submarine offensive against Australia was broken off in July 1943 when the submarines were redeployed to counter Allied offensives elsewhere in the Pacific. The last two Japanese submarines to be dispatched against the Australian east coast, I-177 and I-180, were redirected to the central Solomon Islands shortly before they would have arrived off Australia in July.[66] The Australian Naval authorities were concerned about a resumption of attacks, however, and maintained the coastal convoy system until late 1943 when it was clear that the threat had passed. Coastal convoys in waters south of Newcastle ceased on 7 December and convoys off the north-east coast and between Australia and New Guinea were abolished in February and March 1944 respectively.[67]

Shelling of Port Gregory (January 1943)[]

In contrast to the large number of submarines which operated off the east coast, only a single Japanese submarine was dispatched against the Australian west coast. On 21 January 1943, I-165 left her base at Surabaya, East Java, destined for Western Australia. The submarine—under Lt. Cdr. Kennosuke Torisu—was tasked with creating a diversion to assist the evacuation of Japanese forces from Guadalcanal following their defeat there. Another submarine—I-166—had undertaken a diversionary bombardment of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands on 25 December 1942.[68]

After a six-day voyage southward, I-165 reached Geraldton on 27 January. However, Torisu believed that he had sighted lights of aircraft or a destroyer near the town and broke off his attack. I-165 instead headed north for Port Gregory a former whaling, lead and salt port. At around midnight on 28 January, the submarine's crew fired 10 rounds from her 100 mm (3.9 in) deck gun at the town. The shells appear to have completely missed Port Gregory and did not result in any damage or casualties for the town was not occupied and the raid initially went unnoticed.[69] While gunfire was sighted by nearby coastwatchers, Allied naval authorities only learned of the attack when Lt. Cdr. Torisu's battle report radio signal was intercepted and decoded a week later. As a result, the attack was not successful in diverting attention away from Guadalcanal.[70]

I-165 returned twice to Australian waters. In September 1943, she made an uneventful reconnaissance of the north west coast. I-165 conducted another reconnaissance patrol off north western Australian between 31 May and 5 July 1944. This was the last time a Japanese submarine entered Australian waters.[71]

German raider Michel (June 1943)[]

Michel was the final German surface raider to enter Australian waters and the Pacific. Michel departed from Yokohama, Japan on her second raiding cruise on 21 May 1943 and entered the Indian Ocean in June. On 14 June she sank the 7,715 long tons (7,839 t) Norwegian tanker Høegh Silverdawn[72] about 1,800 miles (1,600 nmi; 2,900 km) north-west of Fremantle. Michel followed up this success two days later by sinking a second Norwegian tanker, the 9,940 long tons (10,100 t) Ferncastle,[73] in the same area. Both tankers were sailing from Western Australia to the Middle East and 47 Allied sailors and passengers were killed as a result of the attacks. Following these sinkings Michel sailed well to the south of Australia and New Zealand and operated in the eastern Pacific. On 3 September, she sank the 9,977 long tons (10,137 t) Norwegian tanker India[74] west of Easter Island with all hands, while the tanker was sailing from Peru to Australia.[75]

1944–1945[]

Landing in the Kimberley (January 1944)[]

While the Japanese government never adopted proposals to invade Australia,[76] a single reconnaissance landing was made on the Australian mainland. Between 17 and 20 January 1944, members of a Japanese intelligence unit named Matsu Kikan ("Pine Tree Organisation") made a reconnaissance mission to a sparsely populated area on the far north coast of the Kimberley region of Western Australia.[77] The unit, operating from Kupang, West Timor, used a converted 25 long tons (25 t) civilian vessel called Hiyoshi Maru and posed as a fishing crew. The mission was led by Lt Susuhiko Mizuno of the Japanese Army and included another three Japanese army personnel, six Japanese naval personnel and 15 West Timorese sailors. Their orders, from the 19th Army headquarters at Ambon, were to verify reports that the U.S. Navy was building a base in the area. In addition, the Matsu Kikan personnel were ordered to collect information which would assist any covert reconnaissance or raiding missions on the Australian mainland.[78]

Hiyoshi Maru left Kupang on 16 January and was given air cover for the outward leg by an Aichi D3A2 "Val" dive bomber which reportedly attacked an Allied submarine en route. On 17 January, Hiyoshi Maru visited the Ashmore Reef area. The following day the crew landed on the tiny and uninhabited Browse Island, about 100 mi (87 nmi; 160 km) north west of the mainland. On the morning of 19 January, Hiyoshi Maru entered York Sound on the mainland. Although the crew saw smoke emanating from hills to the east of their location, they nevertheless anchored and camouflaged the vessel with tree branches. Local historians state that Matsu Kikan landing parties went ashore near the mouth of the Roe River (15°08′16″S 125°23′11″E / 15.13778°S 125.38639°E).[79] They reportedly explored onshore for about two hours, and some members of the mission filmed the area using an 8 mm camera. The Matsu Kikan personnel spent the night on the boat and reconnoitred the area again the following day, before returning to Kupang. The Japanese did not sight any people or signs of recent human activity and little of military significance was learnt from the mission.[78]

Japanese operations in the Indian Ocean (March 1944)[]

In February 1944, the Japanese Combined Fleet withdrew from its base at Truk and was divided between Palau and Singapore. The appearance of a powerful Japanese squadron at Singapore concerned the Allies, as it was feared that this force could potentially conduct raids in the Indian Ocean and against Western Australia.[80]

On 1 March, a Japanese squadron consisting of the heavy cruisers Aoba (flagship), Tone and Chikuma—under Vice Admiral Naomasa Sakonju—sortied from Sunda Strait to attack Allied shipping sailing on the main route between Aden and Fremantle. The only Allied ship this squadron encountered was the British steamer Behar, which was sunk midway between Ceylon and Fremantle on 9 March. Following this attack the squadron broke off its mission and returned to Batavia as it was feared that Allied ships responding to Behar's distress signal posed an unacceptable risk. While 102 survivors from Behar were rescued by Tone, 82 of these prisoners were murdered after the cruiser arrived in Batavia on 16 March. Following the war Vice Adm. Sakonju was executed for war crimes which included the killing of these prisoners, while the former commander of Tone, Capt. Haruo Mayazumi, was sentenced to seven years imprisonment.[81] The sortie mounted by Aoba, Tone and Chikuma was the last raid mounted by Axis surface ships against the Allied lines of communication in the Indian Ocean, or elsewhere, during World War II.[82]

While the Japanese raid into the Indian Ocean was not successful, associated Japanese shipping movements provoked a major Allied response. In early March 1944, Allied intelligence reported that two battleships escorted by destroyers had left Singapore in the direction of Surabaya and a U.S. submarine made radar contact with two large Japanese ships in the Lombok Strait. The Australian Chiefs of Staff Committee reported to the Government on 8 March that there was a possibility that these ships could have entered the Indian Ocean to attack Fremantle. In response to this report, all ground and naval defences at Fremantle were fully manned, all shipping was ordered to leave Fremantle and several RAAF squadrons were redeployed to bases in Western Australia.[83]

This alert proved to be a false alarm, however. The Japanese ships detected in the Lombok Strait were actually the light cruisers Kinu and Ōi which were covering the return of the surface raiding force from the central Indian Ocean. The alert was lifted at Fremantle on 13 March and the RAAF squadrons began returning to their bases in eastern and northern Australia on 20 March.[84]

The German submarine offensive (September 1944 – January 1945)[]

On 14 September 1944, the commander of the Kriegsmarine—Großadmiral (Grand Admiral) Karl Dönitz—approved a proposal to send two Type IXD U-Boats into Australian waters with the objective of tying down Allied anti-submarine assets in a secondary theatre. The U-boats involved were drawn from the Monsun Gruppe ("Monsoon Group"), and the two selected for this operation were German submarine U-168 and German submarine U-862.[85] An additional submarine—U-537—was added to this force at the end of September.[86]

Due to the difficulty of maintaining German submarines in Japanese bases, the German force was not ready to depart from its bases in Penang and Batavia (Jakarta) until early October. By this time, the Allies had intercepted and decoded German and Japanese messages describing the operation and were able to vector Allied submarines onto the German boats. The Dutch submarine Zwaardvisch sank U-168 on 6 October near Surabaya[87] and the American submarine USS Flounder sank U-537 on 10 November near the northern end of the Lombok Strait.[88] Due to the priority accorded to the Australian operation, U-196 was ordered to replace U-168.[89] However, U-196 disappeared in the Sunda Strait some time after departing from Penang on 30 November. The cause of U-196's loss is unknown, though it was probably due to an accident or mechanical fault.[90]

The only surviving submarine of the force assigned to attack Australia—U-862, under Korvettenkapitän Heinrich Timm had left Kiel in May 1944 and reached Penang on 9 September, sinking five merchantmen on the way. She departed Batavia on 18 November 1944, and arrived off the south west tip of Western Australia on 26 November. The submarine had great difficulty finding targets as the Australian naval authorities, warned of U-862's approach, had directed shipping away from the routes normally used. U-862 unsuccessfully attacked the Greek freighter Ilissos off the South Australian coast on 9 December, with bad weather spoiling both the attack and subsequent Australian efforts to locate the submarine.[91][92]

Following her attack on Ilissos, U-862 continued east along the Australian coastline, becoming the only German submarine to operate in the Pacific Ocean during the Second World War.[93] After entering the Pacific U-862 scored her first success on this patrol when she attacked the U.S.-registered Liberty ship Robert J. Walker off the South Coast of New South Wales on 24 December 1944. The ship sank the following day. Following this attack, U-862 evaded an intensive search by Australian aircraft and warships and departed for New Zealand.[94]

As U-862 did not find any worthwhile targets off New Zealand, the submarine's commander planned to return to Australian waters in January 1945 and operate to the north of Sydney. U-862 was ordered to break off her mission in mid-January, however, and return to Jakarta.[95] On her return voyage, the submarine sank another U.S. Liberty ship—Peter Silvester—approximately 820 nmi (940 mi; 1,520 km) southwest of Fremantle on 6 February 1945. Peter Silvester was the last Allied ship to be sunk by the Axis in the Indian Ocean during the war.[96] U-862 arrived in Jakarta in mid February 1945 and is the only Axis ship known to have operated in Australian waters during 1945. Following Germany's surrender, U-862 became the Japanese submarine I-502 but was not used operationally.[97]

While Allied naval authorities were aware of the approach of the German strike force and were successful in sinking two of the four submarines dispatched, efforts to locate and sink U-862 once she reached Australian waters were continually hampered by a lack of suitable ships and aircraft and a lack of personnel trained and experienced in anti-submarine warfare.[98] As the southern coast of Australia was thousands of kilometres behind the active combat front in South-East Asia and had not been raided for several years, it should not be considered surprising that few anti-submarine assets were available in this area in late 1944 and early 1945.[99]

Conclusions[]

Casualties[]

A total of six German surface raiders, four Japanese aircraft carriers, seven Japanese cruisers, nine Japanese destroyers and twenty eight Japanese and German submarines operated in Australian waters between 1940 and 1945. These 54 warships sank 53 merchant ships and three warships within the Australia Station, resulting in the deaths of over 1,751 Allied military personnel, sailors and civilians. Over 88 people were also killed by IJN air attacks on towns in northern Australia. In exchange, the Allies sank one German surface raider, one full-sized Japanese submarine and two midget submarines within Australian waters, resulting in the deaths of 157 Axis sailors. A further two German submarines were sunk while en route to Australian waters with the loss of 81 sailors.[101]

- The six German and three Japanese surface raiders that operated within Australian waters sank 18 ships and killed over 826 sailors (including the 82 prisoners murdered on board Tone in 1944). Kormoran was the only Axis surface ship to be sunk within the Australia Station, and 78 of her crew were killed.[102]

- The 17 ships in the Japanese carrier force that raided Darwin in 1942 sank nine ships and killed 251 people for the loss of four aircraft.[103] A further 14 sailors and civilians were killed in the sinking of HMAS Patricia Cam and the attacks on Period and Islander in 1943 and 88 people were killed during the raid on Broome in 1942.

- The 28 Japanese and German submarines that operated in Australian waters between 1942 and 1945 sank a total of 30 ships with a combined tonnage of 151,000 long tons (153,000 t); 654 people, including 200 Australian merchant seamen, were killed on board the ships attacked by submarines.[104] It has also been estimated that the RAAF lost at least 23 aircraft and 104 airmen to flying accidents during anti-submarine patrols off the Australian coast.[105] In exchange, the Allies sank only a single full-sized Japanese submarine in Australian waters (I-124) and two of the three midgets that entered Sydney Harbour. A total of 79 Japanese sailors died in these sinkings, and a further two sailors died on board the third midget, which was scuttled after leaving Sydney Harbour.[106]

Assessment[]

While the scale of the Axis naval offensive directed against Australia was small compared to other naval campaigns of the war such as the Battle of the Atlantic, they were still "the most comprehensive and widespread series of offensive operations ever conducted by an enemy against Australia".[107] Due to the limited size of the Australian shipping industry and the importance of sea transport to the Australian economy and Allied military in the South West Pacific, even modest shipping losses had the potential to seriously damage the Allied war effort in the South West Pacific.[28]

Despite the vulnerability of the Australian shipping industry, the Axis attacks did not seriously affect the Australian or Allied war effort. While the German surface raiders which operated against Australia caused considerable disruption to merchant shipping and tied down Allied naval vessels, they did not sink many ships and only operated in Australian waters for a few short periods.[108] The effectiveness of the Japanese submarine campaign against Australia was limited by the inadequate numbers of submarines committed and flaws in Japan's submarine doctrine. The submarines were, however, successful in forcing the Allies to devote considerable resources to protecting shipping in Australian waters between 1942 and late 1943.[109] The institution of coastal convoys between 1942 and 1943 may have also significantly reduced the efficiency of the Australian shipping industry during this period.[110]

The performance of the Australian and Allied forces committed to the defence of shipping on the Australia station was mixed. While the threat to Australia from Axis raiders was "anticipated and addressed",[111] only a small proportion of the Axis ships and submarines which attacked Australia were successfully located or engaged. Several German raiders operated undetected within Australian waters in 1940 as the number of Allied warships and aircraft available were not sufficient to patrol these waters[112] and the loss of HMAS Sydney was a high price to pay for sinking Kormoran in 1941. While the Australian authorities were quick to implement convoys in 1942 and no convoyed ship was sunk during that year, the escorts of the convoys that were attacked in 1943 were not successful in either detecting any submarines before they launched their attack or successfully counter-attacking these submarines.[113] Factors explaining the relatively poor performance of Australian anti-submarine forces include their typically low levels of experience and training, shortages of ASW assets, problems with co-ordinating searches and the poor sonar conditions in the waters surrounding Australia.[114] Nevertheless, "success in anti-submarine warfare cannot be measured simply by the total of sinkings achieved" and the Australian defenders may have successfully reduced the threat to shipping in Australian waters by making it harder for Japanese submarines to carry out attacks.[114][115]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ G. Herman Gill (1957). Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. Volume I – Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942. Australian War Memorial, Canberra. pp. 52–53.

- ^ Gill (1957). p. 51.

- ^ Alastair Cooper (2001). Raiders and the Defence of Trade: The Royal Australian Navy in 1941. Paper delivered to the Australian War Memorial conference Remembering 1941.

- ^ Douglas Gillison (1962) Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 3 – Air. Volume I – Royal Australian Air Force, 1939–1942. Australian War Memorial, Canberra. pp. 93–94.

- ^ Straczek, J.H. "RAN in the Second World War". Royal Australian Navy. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ George Odgers (1968) Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 3 – Air. Volume II – Air War Against Japan, 1943–1945. Australian War Memorial, Canberra. p. 349.

- ^ Albert Palazzo (2001). The Australian Army : A History of its Organisation 1901–2001. Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2001. p. 136.

- ^ Palazzo (2001). pp. 155–157.

- ^ David Stevens (2005), RAN Papers in Australian Maritime Affairs No. 15 A Critical Vulnerability: The impact of the submarine threat on Australia's maritime defence 1915–1954 Archived 9 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine . Seapower Centre – Australia, Canberra. pp. 95–97.

- ^ Stevens (2005). p. 173.

- ^ Gill (1957). p. 420.

- ^ Stevens (2005). pp. 330–332.

- ^ Gill (1957). pp. 118–124.

- ^ Gill (1957). p. 261.

- ^ Gill (1957). p. 262.

- ^ Warsailors.com: M/T Storstad

- ^ Gill (1957). pp. 270–276.

- ^ Gill (1957). pp. 276–279.

- ^ Gill (1957). p. 281.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gill (1957). p. 410.

- ^ Gill (1957). pp. 282–283.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gill (1957). p. 284.

- ^ Gill (1957). p. 283.

- ^ Gill (1957). pp. 446–447.

- ^ The action between HMAS Sydney and the auxiliary cruiser Kormoran, 19 November 1941, Australian War Memorial, accessed 12 June 2006

- ^ Tom Frame (1993). HMAS Sydney. Loss and Controversy. Hodder & Stoughton, Sydney. p. 177.

- ^ Gill (1968). pp. 197–198.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stevens (2005). p. 330.

- ^ Stevens (2005). p. 183.

- ^ Stevens (2005). pp. 183–184. The only other Axis submarines sunk in Australian waters were two of the three midget submarines which entered Sydney Harbour in May 1942.

- ^ McCarthy, M., (1990) HIJMS Submarine I 124. (1990) Report_ Department of Maritime Archaeology Western Australian Maritime Museum, No 43

- ^ Stevens (2005). pp. 185–186.

- ^ Sydney David Waters (1956), The Royal New Zealand Navy. Historical Publications Branch, Wellington. pp. 214–215.

- ^ Tom Lewis (2003). A War at Home. A Comprehensive guide to the first Japanese attacks on Darwin. Tall Stories, Darwin. p. 16.

- ^ David Jenkins (1992), Battle Surface! Japan's Submarine War Against Australia 1942–44. Random House Australia, Sydney. pp. 118–120 and Lewis (2003). pp. 63–71.

- ^ Samuel Eliot Morison (1949 (2001 reprint)). Coral Sea, Midway and Submarine Actions, May 1942 – August 1942, Volume 4 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. University of Illinois Press, Champaign. pp. 12–13.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). pp. 261–262.

- ^ Gill (1968). pp. 264–266.

- ^ David Horner (1993). 'Defending Australia in 1942' in War and Society, Volume 11, Number 1, May 1993. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Horner (1993). p. 10.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). p. 163.

- ^ Stevens (2005). pp. 191–192.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). p. 165.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). pp. 163–164.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). p. 171.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). pp. 174–175.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). pp. 185–193.

- ^ Robert Nichols 'The Night the War Came to Sydney' in Wartime Issue 33, 2006. pp. 26–29

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stevens (2005). p. 195.

- ^ G. Herman Gill (1968). Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. Volume II – Royal Australian Navy, 1942–1945. Australian War Memorial, Canberra. pp. 77–78.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). p. 291.

- ^ Stevens (2005). p. 201.

- ^ Stevens (2005). pp. 206–207.

- ^ Stevens (2005). p. 205.

- ^ Stevens (2005). pp. 218–220.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). pp. 268–272.

- ^ Stevens (2005). pp. 223–224.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). pp. 272–273.

- ^ Stevens (2005). pp. 230–231.

- ^ Gill (1968). pp. 253–262.

- ^ Gill (1968). pp. 261–262.

- ^ Crowhust (2012). pp. 29–30

- ^ Hackett, Bob; Kingsepp, Sander (2001). "IJN Submarine I-178: Tabular Record of Movement". combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). pp. 277–285.

- ^ Tom Frame (2004), No Pleasure Cruise: The Story of the Royal Australian Navy. Allen & Unwin, Sydney. pp. 186–187.

- ^ Stevens (2005). p. 246.

- ^ Stevens (2005). pp. 246–248.

- ^ David Stevens, 'Forgotten assault' in Wartime Issue 18, 2002.

- ^ Jenkins (1992). pp. 266–267.

- ^ Stevens (2002)

- ^ Jenkins (1992). p. 286.

- ^ Warsailors.com: M/T Høegh Silverdawn

- ^ Warsailors.com: M/T Ferncastle

- ^ Warsailors.com: M/T India

- ^ Gill (1968). p. 297 and Bismarck-class.dk Hilfskreuzer (Auxiliary Cruiser) Michel Archived 10 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 3 June 2007.

- ^ Peter Stanley (2002). He's (Not) Coming South: The Invasion That Wasn't

- ^ Peter Dunn Japanese Army reconnaissance party landed in Western Australia near Cartier and Brows Islands. Accessed 2 November 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Henry P. Frei (1991), Japan's Southward Advance and Australia. From the Sixteenth Century to World War II. Melbourne University Press, Melbourne. p. 173.

- ^ Daphne Choules Edinger, 1995, "Exploring the Kimberley Coast" and; Cathie Clement, 1995, "World War II and the Kimberley" (The Kimberley Society)

- ^ Odgers (1968). pp. 134–135.

- ^ Children & Families of Far East Prisoners of War. The Behar. Accessed 21 July 2017.

- ^ Gill (1968). p. 390

- ^ Odgers (1968). pp. 136–139.

- ^ Gill (1968). pp. 390–391.

- ^ Stevens (2005). p. 262.

- ^ David Stevens (1997), U-Boat Far from Home. Allen & Unwin, Sydney. p. 119.

- ^ Paul Kemp (1997), U-Boats Destroyed. German Submarine Losses in the World Wars. Arms and Armour, London. p. 221.

- ^ Kemp (1997). p. 224.

- ^ Stevens (1997). p. 124.

- ^ Kemp (1997). p. 225. Kemp suggests that U-196 may have been lost in a diving accident or due to a fault in the boat's locally constructed snorkel.

- ^ Stevens (1997). pp. 147–151.

- ^ Cooke, Peter (2000). Defending New Zealand: Ramparts on the Sea 1840–1950s (Part I). Wellington: Defence of New Zealand Study Group. pp. 426–428. ISBN 0-473-06833-8.

- ^ Uboat.net The Monsun boats. Accessed 5 August 2006.

- ^ Stevens (1997). pp. 159–173.

- ^ Stevens (2005). p. 278.

- ^ Gill (1968). p. 557.

- ^ Stevens (1997). p. 222.

- ^ Stevens (2005). p. 258.

- ^ Stevens (1997). pp. 164–165.

- ^ Caption to the copy of this poster on display in the Second World War gallery of the Australian War Memorial

- ^ Uboat.net U-168 and U-537. Accessed 7 October 2006.

- ^ Figures compiled from Gill (1957).

- ^ Lewis (2003).

- ^ Jenkins (1992). pp. 286–287.

- ^ David Joseph Wilson (2003) The Eagle and the Albatross : Australian Aerial Maritime Operations 1921–1971. PhD thesis. p. 120.

- ^ Figures compiled from Jenkins (1992).

- ^ David Stevens. Japanese submarine operations against Australia 1942–1944 Archived 19 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 1 September 2006.

- ^ Alastair Cooper (2001).

- ^ Stevens. Japanese submarine operations against Australia 1942–1944 Archived 19 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 1 September 2006.

- ^ Stevens (2005). p. 334.

- ^ Seapower Centre – Australia (2005). The Navy Contribution to Australian Maritime Operations Archived 26 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine . Defence Publishing Service, Canberra. p. 179.

- ^ Gavin Long (1973), The Six Years War. A Concise History of Australia in the 1939–45 War. Australian War Memorial and Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra. p. 33.

- ^ Stevens (2005). p. 331.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stevens (2005). p. 281.

- ^ Odgers (1968). p. 153.

References[]

Books and printed material[]

- Australia in the War of 1939–1945

- G. Herman Gill (1957), Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. Volume I 1939–1942. Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

- G. Herman Gill (1968), Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. Volume II – Royal Australian Navy, 1942–1945. Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

- Douglas Gillison (1962), Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 3 – Air. Volume I – Royal Australian Air Force, 1939–1942. Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

- George Odgers (1968), Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 3 – Air. Volume II – Air War Against Japan, 1943–1945. Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

- Gavin Long (1973), The Six Years War. A Concise History of Australia in the 1939–45 War. Australian War Memorial and Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra. ISBN 0-642-99375-0

- Steven L Carruthers (1982), Australia Under Siege: Japanese Submarine Raiders, 1942. Solus Books. ISBN 0-9593614-0-5

- John Coates (2001), An Atlas of Australia's Wars. Oxford University Press, Melbourne. ISBN 0-19-554119-7

- Crowhurst, Geoff (2012). "Who Sank I-178?". The Navy. 75 (1): 27–30. ISSN 1322-6231.

- Tom Frame (1993), HMAS Sydney. Loss and Controversy. Hodder & Stoughton, Sydney. ISBN 0-340-58468-8

- Tom Frame (2004), No Pleasure Cruise: The Story of the Royal Australian Navy. Allen & Unwin, Sydney. ISBN 1-74114-233-4

- Henry P. Frei (1991), Japan's Southward Advance and Australia. From the Sixteenth Century to World War II. Melbourne University Press, Melbourne. ISBN 0-522-84392-1

- David Horner (1993). 'Defending Australia in 1942' in War and Society, Volume 11, Number 1, May 1993.

- David Jenkins (1992), Battle Surface! Japan's Submarine War Against Australia 1942–44. Random House Australia, Sydney. ISBN 0-09-182638-1

- Paul Kemp (1997), U-Boats Destroyed. German Submarine Losses in the World Wars. Arms and Armour, London. ISBN 1-85409-321-5

- Tom Lewis (2003). A War at Home. A Comprehensive guide to the first Japanese attacks on Darwin. Tall Stories, Darwin. ISBN 0-9577351-0-3

- Samuel Eliot Morison (1949 (2001 reprint)). Coral Sea, Midway and Submarine Actions, May 1942 – August 1942, Volume 4 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. University of Illinois Press, Champaign. ISBN 0-252-06995-1

- Robert Nichols 'The Night the War Came to Sydney' in Wartime Issue 33, 2006.

- Albert Palazzo (2001). The Australian Army : A History of its Organisation 1901–2001. Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2001. ISBN 0-19-551506-4

- Seapower Centre – Australia (2005). The Navy Contribution to Australian Maritime Operations. Defence Publishing Service, Canberra. ISBN 0-642-29615-4

- David Stevens, 'The War Cruise of I-6, March 1943' in Australian Defence Force Journal No. 102 September/October 1993. pp. 39–46.

- David Stevens (1997), U-Boat Far from Home. Allen & Unwin, Sydney. ISBN 1-86448-267-2

- David Stevens, 'Forgotten assault' in Wartime Issue 18, 2002.

- David Stevens (2005), RAN Papers in Australian Maritime Affairs No. 15 A Critical Vulnerability: The impact of the submarine threat on Australia's maritime defence 1915–1954. Seapower Centre – Australia, Canberra. ISBN 0-642-29625-1

- Sydney David Waters (1956), The Royal New Zealand Navy. Historical Publications Branch, Wellington.

External links and articles[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Axis naval activity in Australian waters. |

- Alastair Cooper (2001). Raiders and the Defence of Trade: The Royal Australian Navy in 1941. Paper delivered to the Australian War Memorial conference Remembering 1941.

- Bob Hackett and Sander Kingsepp (2006). combinedfleet.com – Japanese Submarines

- Tanaka Hiromi 'The Japanese Navy's operations against Australia in the Second World War, with a commentary on Japanese sources' in The Journal of the Australian War Memorial. Issue 30 – April 1997.

- Dr. Peter Stanley (2002). He's (Not) Coming South: The Invasion That Wasn't. Paper delivered to the Australian War Memorial conference Remembering 1942.

- Dr. Peter Stanley (2006). Was there a Battle for Australia? Australian War Memorial Anniversary Oration, 10 November 2006.

- David Stevens Japanese submarine operations against Australia 1942–1944.

- U-boat.net Monsun boats U-boats in the Indian Ocean and the Far East

Further reading[]

- Arnold, Anthony (2013). "A Slim Barrier: The Defence of Mainland Australia 1939–1945". PhD Thesis. University of New South Wales.

- Miles, Patricia (2012). "War casualties and the Merchant Navy". Office of Environment and Heritage.

- Conflicts in 1940

- Conflicts in 1941

- Conflicts in 1942

- Conflicts in 1943

- Conflicts in 1944

- Conflicts in 1945

- Military attacks against Australia

- South West Pacific theatre of World War II

- 1940s in Australia

- Military history of Japan during World War II

- Australia–Japan relations

WikiMiniAtlas

WikiMiniAtlas