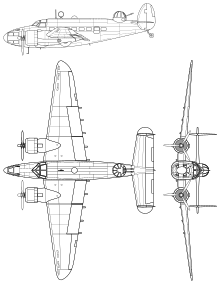

Lockheed Hudson

| Hudson A-28 / A-29 / AT-18 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lockheed A-29 Hudson | |

| Role | Bomber, reconnaissance, transport, maritime patrol aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed |

| Designer | Clarence "Kelly" Johnson |

| First flight | 10 December 1938 |

| Introduction | 1939 |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force Royal Canadian Air Force Royal Australian Air Force United States Army Air Forces |

| Produced | 1938–1943 |

| Number built | 2,941 |

| Developed from | Lockheed Model 14 Super Electra |

The Lockheed Hudson was an American-built light bomber and coastal reconnaissance aircraft built initially for the Royal Air Force shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War and primarily operated by the RAF thereafter. The Hudson was a military conversion of the Lockheed Model 14 Super Electra airliner, and was the first significant aircraft construction contract for the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation—the initial RAF order for 200 Hudsons far surpassed any previous order the company had received.[1][2][3] The Hudson served throughout the war, mainly with Coastal Command but also in transport and training roles as well as delivering agents into occupied France. They were also used extensively with the Royal Canadian Air Force's anti-submarine squadrons and by the Royal Australian Air Force.

Design and development[]

In late 1937 Lockheed sent a cutaway drawing of the Model 14 to various publications, showing the new aircraft as a civilian aircraft and converted to a light bomber.[4] This attracted the interest of various air forces and in 1938, the British Purchasing Commission sought an American maritime patrol aircraft for the United Kingdom to support the Avro Anson.

The British Purchasing Commission ordered 200 aircraft for use by the Royal Air Force and the first aircraft started flight trials from Burbank on 10 December 1938.[5] The flight trials showed no major issues and deliveries to the RAF began on 15 February 1939.[5] Production was sped up after the British indicated they would order another 50 aircraft if the original 200 could be delivered before the end of 1939.[5] Lockheed sub-contracted some parts assembly to Rohr Aircraft of San Diego and increased its workforce, allowing the company to produce the 250th aircraft seven and a half weeks before the deadline.[5]

A total of 350 Mk I and 20 Mk II Hudsons were supplied (the Mk II had different propellers). These had two fixed Browning machine guns in the nose and two more in the Boulton Paul dorsal turret. The Hudson Mk III added one ventral and two beam machine guns and replaced the 1,100 hp Wright R-1820 Cyclone 9-cylinder radials with 1,200 hp versions (428 produced).[6]

The Hudson Mk V (309 produced) and Mk VI (450 produced) were powered by the 1,200 hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp 14-cylinder two-row radial. The RAF also obtained 380 Mk IIIA and 30 Mk IV Hudsons under the Lend-Lease programme.

Operational history[]

World War II[]

By February 1939, RAF Hudsons began to be delivered, initially equipping No. 224 Squadron RAF at RAF Leuchars, Scotland in May 1939. By the start of the war in September, 78 Hudsons were in service.[7] Due to the United States' neutrality at that time, early series aircraft were flown to the Canada–US border, landed, and then towed on their wheels over the border into Canada by tractors or horse drawn teams, before then being flown to Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) airfields where they were then dismantled and "cocooned" for transport as deck cargo, by ship to Liverpool. The Hudsons were supplied without the Boulton Paul dorsal turret, which was installed on arrival in the United Kingdom.

Although later outclassed by larger bombers, the Hudson achieved some significant feats during the first half of the war. On 8 October 1939, over Jutland, a Hudson became the first Allied aircraft operating from the British Isles to shoot down an enemy aircraft[8] (earlier victories by a Fairey Battle on 20 September 1939 over Aachen and by Blackburn Skuas of the Fleet Air Arm on 26 September 1939 had been by aircraft based in France or on an aircraft carrier). Hudsons also provided top cover during the Battle of Dunkirk.

On 27 August 1941, a Hudson of No. 269 Squadron RAF, operating from Kaldadarnes, Iceland, attacked and damaged the German submarine U-570 causing the submarine's crew to display a white flag and surrender – the aircraft achieved the unusual distinction of capturing a naval vessel. The Germans were taken prisoner and the submarine taken under tow when Royal Navy ships subsequently arrived on the scene.[9] A PBO-1 Hudson of the United States Navy squadron VP-82 became the first US aircraft to destroy a German submarine,[10] when it sank U-656 southwest of Newfoundland on 1 March 1942. U-701 was destroyed on 7 July 1942 while running on the surface off Cape Hatteras by a Hudson of the 396th Bombardment Squadron (Medium), United States Army Air Forces (USAAF). A Hudson of No. 113 Squadron RCAF became the first aircraft of the RCAF's Eastern Air Command to sink a submarine, when Hudson 625 sank U-754 on 31 July 1942.[11]

A Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Hudson was involved in the Canberra air disaster of 1940, in which three ministers of the Australian government were killed.

In 1941, the USAAF began operating the Hudson; the Twin Wasp-powered variant was designated the A-28 (82 acquired) and the Cyclone-powered variant was designated the A-29 (418 acquired). The US Navy operated 20 A-29s, redesignated the PBO-1. A further 300 were built as aircrew trainers, designated the AT-18.

Following Japanese attacks on Malaya, Hudsons from No. 1 Squadron RAAF became the first Allied aircraft to make an attack in the Pacific War, sinking a Japanese transport ship, the Awazisan Maru, off Kota Bharu at 0118h local time, an hour before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Its opponents found that the Hudson had exceptional manoeuvrability for a twin-engine aircraft; it was notable for the tight turns achievable if either engine was briefly feathered.

- The highest-scoring Japanese ace of the war, Saburō Sakai, praised the skill and fighting abilities of an RAAF Hudson crew killed in action over New Guinea after being engaged by nine highly manoeuvrable Mitsubishi A6M Zeroes on 22 July 1942.[12][13] The crew, captained by P/O Warren Cowan, in Hudson Mk IIIA A16-201 (bu. no. 41-36979) of No. 32 Squadron RAAF, was intercepted over Buna by nine Zeroes of the Tainan Kaigun Kōkūtai led by Sakai. The Hudson crew accomplished many aggressive and unexpected turns, engaging the Japanese pilots in a dogfight for more than 10 minutes. It was only after Sakai scored hits on the rear/upper turret that the Hudson could be destroyed. Its crew made such an impression on Sakai that, after the war's end, he sought to identify them. In 1997, Sakai wrote formally to the Australian government, recommending that Cowan be "posthumously awarded your country's highest military decoration".[12]

- On 23 November 1942, the crew of a No. 3 Squadron, Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) Hudson Mk IIIA, NZ2049,[14] (41-46465) after spotting an enemy convoy near Vella Lavella, was engaged by three Japanese floatplane fighters. After skilled evasive manoeuvring at an altitude of less than 50 feet (15 metres), by the Hudson's captain, Flying Officer George Gudsell,[15] the crew returned with no casualties to Henderson Field, Guadalcanal.

Hudsons were also operated by RAF Special Duties squadrons for clandestine operations; No. 161 Squadron in Europe and No. 357 Squadron in Burma.

Postwar use[]

After the war, numbers of Hudsons were sold by the military for civil operation as airliners and survey aircraft. In Australia, East-West Airlines of Tamworth, New South Wales (NSW), operated four Hudsons on scheduled services from Tamworth to many towns in NSW and Queensland between 1950 and 1955.[16] Adastra Aerial Surveys based at Sydney's Mascot Airport operated seven L-414s between 1950 and 1972 on air taxi, survey and photographic flights.[17]

A total of 2,941 Hudsons were built.[18]

The type formed the basis for development of the Lockheed Ventura resulting in them being withdrawn from front line service from 1944, though many survived the war to be used as civil transports, primarily in Australia and a single example was briefly used as an airline crew trainer in New Zealand.

Variants[]

- Model 414

- Company designation for the military A-28 / A-29 and Hudson variants.

- Hudson I

- Production aircraft for the Royal Air Force (RAF); 351 built and 50 for the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF).

- Hudson II

- As the Mk I but with spinnerless constant speed propellers; 20 built for the RAF and 50 for the RAAF.

- Hudson III

- Production aircraft with retractable ventral gun position; 428 built.

- Hudson IIIA

- Lend-lease variants of the A-29 and A-29A aircraft; 800 built.

- Hudson IV

- As Mk II with ventral gun removed; 30 built and RAAF Mk I and IIs were converted to this standard.

- Hudson IVA

- 52 A-28s delivered to the RAAF.

- Hudson V

- Mk III with two 1,200 hp (890 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-1830-S3C4-G Twin Wasp engines; 409 built.

- Hudson VI

- A-28As under lend-lease; 450 built.

- A-28

- US Military designation powered by two 1,050 hp (780 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-1830-45 engines; 52 lend-lease to Australia as Hudson IVA.[19]

- A-28A

- US Military designation powered by two 1,200 hp (890 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-1830-67 engines, interiors convertible to troop transports; 450 lend-lease to RAF/RCAF/RNZAF as Hudson VI; 27 units passed to the Brazilian Air Force.[19]

- A-29

- US Military designation powered by two 1,200 hp (890 kW) Wright R-1820-87 engines; lend lease version intended for the RAF, 153 diverted to United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) as the RA-29 and 20 to the United States Navy (USN) as the PBO-1.[19]

- A-29A

- as A-29 but with convertible interiors as troop transports; 384 lend-lease to the RAF/RAAF/RCAF/RNZAF Chinese Air Force as Hudson IIIA, some retained by USAAF as the RA-29A.[19]

- A-29B

- 24 of the 153 A-29s retained by the USAAF converted for photo-survey.[19]

- AT-18

- Gunnery trainer version of the A-29 powered by two Wright R-1820-87 engines, 217 built.

- AT-18A

- Navigational trainer version with dorsal turret removed, 83 built.

- C-63

- Provisional designation changed to A-29A.

- PBO-1

- Twenty former RAF Hudson IIIAs repossessed for use by Patrol Squadron 82 (VP-82) of the USN

Operators[]

Australia

Australia

- Royal Australian Air Force

- Squadrons serving in the Pacific War:

- No. 1 Squadron RAAF

- No. 2 Squadron RAAF

- No. 6 Squadron RAAF

- No. 7 Squadron RAAF

- No. 8 Squadron RAAF

- No. 13 Squadron RAAF

- No. 14 Squadron RAAF

- No. 23 Squadron RAAF

- No. 24 Squadron RAAF

- No. 32 Squadron RAAF

- No. 1 Operational Training Unit RAAF

- Article XV squadrons serving with RAF Middle East Command:

- No. 459 Squadron RAAF

- Squadrons serving in the Pacific War:

Brazil

Brazil

- Brazilian Air Force

- 2nd Medium Bomber Group (27 units A-28A)

Canada

Canada

- Royal Canadian Air Force

- Squadrons serving with the Home War Establishment (HWE):

- No. 11 Squadron RCAF

- No. 113 Squadron RCAF

- No. 119 Squadron RCAF

- No. 145 Squadron RCAF

- Article XV squadrons serving with RAF Coastal Command:

- No. 407 Squadron RCAF

- Squadrons serving with the Home War Establishment (HWE):

- Chinese Nationalist Air Force

Ireland

Ireland

- Irish Air Corps

Israel

Israel

- Israeli Air Force

Netherlands

Netherlands

- Royal Netherlands Air Force

- No. 320 Squadron RAF

New Zealand

New Zealand

- Royal New Zealand Air Force

- No. 1 Squadron RNZAF

- No. 2 Squadron RNZAF

- No. 3 Squadron RNZAF

- No. 4 Squadron RNZAF

- No. 9 Squadron RNZAF

- No. 40 Squadron RNZAF

- No. 41 Squadron RNZAF

- No. 42 Squadron RNZAF

Portugal

Portugal

- Portugal Air Force

South Africa

South Africa

- South African Air Force

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

- Royal Air Force

- No. 24 Squadron RAF

- No. 48 Squadron RAF

- No. 53 Squadron RAF

- No. 59 Squadron RAF

- No. 62 Squadron RAF

- No. 117 Squadron RAF

- No. 139 Squadron RAF

- No. 161 Squadron RAF

- No. 163 Squadron RAF

- No. 194 Squadron RAF

- No. 200 Squadron RAF

- No. 203 Squadron RAF

- No. 206 Squadron RAF

- No. 212 Squadron RAF

- No. 217 Squadron RAF

- No. 220 Squadron RAF

- No. 224 Squadron RAF

- No. 231 Squadron RAF

- No. 233 Squadron RAF

- No. 251 Squadron RAF

- No. 267 Squadron RAF

- No. 269 Squadron RAF

- No. 271 Squadron RAF

- No. 279 Squadron RAF

- No. 285 Squadron RAF

- No. 287 Squadron RAF

- No. 288 Squadron RAF

- No. 289 Squadron RAF

- No. 353 Squadron RAF

- No. 357 Squadron RAF

- No. 500 Squadron RAF

- No. 517 Squadron RAF

- No. 519 Squadron RAF

- No. 520 Squadron RAF

- No. 521 Squadron RAF

- No. 608 Squadron RAF

- Communication Flight Iraq and Persia[20]

- Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm

- 4 aircraft from Royal Air Force

United States

United States

- Sperry Gyroscope

- United States Army Air Forces

- United States Navy

Civil operators[]

Australia

Australia

- East-West Airlines

- Adastra Air Surveys[21]

Portugal

Portugal

- TAP – Transportes Aéreos Portugueses

Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago

- British West Indian Airways

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

- BOAC – British Overseas Airways Corporation

Surviving aircraft[]

- Australia

- A16-105 – Hudson IV on static display at Canberra Airport in Pialligo, Australian Capital Territory.[22] It is owned by the Australian War Memorial and was restored at the museum's Treloar Technology Centre.[23][24][25][26]

- A16-112 – Hudson IV airworthy at the Temora Aviation Museum in Temora, New South Wales. It is painted as a Hudson III, serial number A16-211, with the nose art The Tojo Busters.[27][28][29][30] Ownership was transferred to the RAAF in July 2019 and it is operated by the Air Force Heritage Squadron (Temora Historic Flight).

- A16-122 – Hudson IVA in storage at the RAAF Museum in Point Cook, Victoria.[31][32]

- Canada

- BW769 – Hudson IIIA on static display at the North Atlantic Aviation Museum in Gander, Newfoundland and Labrador. It was previously mounted on a pedestal near Gander International Airport for many years. It is painted as T9422.[33]

- FK466 - Hudson VI under restoration at the National Air Force Museum of Canada in Trenton, Ontario.[34]

- New Zealand

- NZ2013 – Hudson III on static display at the Air Force Museum of New Zealand in Wigram, Canterbury.[35]

- NZ2031 – Hudson III on static display at the Museum of Transport and Technology in Western Springs, Auckland.[36][37]

- NZ2035 – Hudson III under restoration at the Ferrymead Aeronautical Society at Ferrymead Heritage Park in Christchurch, Canterbury.[38][39]

- NZ2049 – Hudson IIIA owned by Bill Reid[40][41] and on display at the Omaka Aviation Heritage Centre.

- NZ2084 – Hudson IIIA with Nigel Wilcox in Christchurch, Canterbury.[40][41]

- Unknown – Unknown fuselage under restoration to static display in a private collection near Ardmore Aerodrome near Manurewa, Auckland.[citation needed]

- United Kingdom

- A16-199 – Hudson IIIA on static display at the Royal Air Force Museum London in London. It is painted in the colours of the 13 Squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force.[42][43][44]

Specifications (Hudson Mk I)[]

Data from Lockheed Aircraft since 1913[45]

General characteristics

- Crew: Five

- Length: 44 ft 4 in (13.51 m)

- Wingspan: 65 ft 6 in (19.96 m)

- Height: 11 ft 10 in (3.61 m)

- Wing area: 551 sq ft (51.2 m2)

- Empty weight: 11,630 lb (5,275 kg)

- Gross weight: 17,500 lb (7,938 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Wright GR-1820-G102A Cyclone 9-cylinder radial engines, 1,100 hp (820 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 246 mph (396 km/h, 214 kn) at 6,500 ft (2,000 m)

- Cruise speed: 220 mph (350 km/h, 190 kn)

- Range: 1,960 mi (3,150 km, 1,700 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 25,000 ft (7,600 m)

- Rate of climb: 2,180 ft/min (11.1 m/s)

Armament

- Guns:

- 2 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns in dorsal turret

- 2× .303 Browning machine guns in nose

- Bombs: 1,400 lb (640 kg) of bombs or depth charges

See also[]

- Aircraft in fiction#Lockheed Hudson

Related development

- Lockheed Model 14 Super Electra

- Lockheed Ventura

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Avro Anson

- Bristol Blenheim

- Dornier Do 17

- Martin Maryland

- PZL.37 Łoś

- Tupolev SB

Related lists

- List of aircraft of World War II

- List of aircraft of the Royal Air Force

- List of aircraft of the Royal New Zealand Air Force and Royal New Zealand Navy

- List of military aircraft of the United States

- List of Lockheed aircraft

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ Herman 2012, pp. 11, 85, 86.

- ^ Parker 2013, pp. 59, 71.

- ^ Borth 1945, p. 244.

- ^ Bonnier Corporation (November 1937). "New Transport Plane Can Be Converted To Bomber". Popular Science Monthly. Bonnier Corporation. p. 64.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Francillon 1982, p. 146.

- ^ Parker 2013, p. 71.

- ^ Kightly 2015, p. 80.

- ^ "Collections: Lockheed Hudson IIIA." RAF Museum. Retrieved: 15 October 2014.

- ^ Thomas, Andrew. "Icelandic Hunters - No 269 Squadron Royal Air Force." Aviation News, 24 May 2001. Retrieved: 15 October 2014.

- ^ Swanborough and Bowers 1976, p. 505.

- ^ Douglas 1986, p. 520.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Australian Story: Enemy Lines". ABC-TV, 2002. Retrieved: 30 April 2014.

- ^ Birkett, Gordon. "RAAF A16 Lockheed Hudson Mk.I/Mk.II/Mk.III/Mk.IIIA/Mk.IV/MK.IVA". ADF-Serials, 2013. Retrieved: 30 April 2014.

- ^ "RNZAF Lockheed Hudson Survivors." Cambridge Air Force, 2008. Retrieved: 15 July 2010.

- ^ "A Veteran's Advice." Archived 2010-05-22 at the Wayback Machine rsa.org.nz. Retrieved: 15 July 2010.

- ^ Marson 2001, p. 110.

- ^ Marson 2001, p. 76.

- ^ Francillon 1987, pp. 148, 501–502.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Francillon 1982, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Lake 1999, p. 5

- ^ "LOCKHEED HUDSON". Adastra Aerial Surveys. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Connery, Georgina (22 December 2016). "Restored Lockheed Hudson bomber on display at Canberra Airport". The Canberra Times. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ "Lockheed Hudson Mk IV bomber A16-105 : 1 Operational Training Unit, RAAF". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Blog: Lockheed Hudson Mk IV bomber A16-105". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Airframe Dossier - Lockheed Hudson IV, s/n A16-105 RAAF, c/n 414-6034, c/r VH-AGP". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Cuskelly, Ron (25 October 2016). "VH-AGP". Adastra Aerial Surveys. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Lockheed Hudson". Temora Aviation Museum. Temora Aviation Museum. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Airframe Dossier - Lockheed Hudson IV, s/n A16-112 RAAF, c/n 414-6041, c/r VH-KOY". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Aircraft Register [VH-KOY]". Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Cuskelly, Ron (26 February 2016). "VH-AGS". Adastra Aerial Surveys. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Airframe Dossier - Lockheed Hudson IVA, s/n A16-122 RAAF, c/n 414-6051, c/r VH-AGX". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Cuskelly, Ron (12 September 2016). "VH-AGX". Adastra Aerial Surveys. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Lockheed Hudson Bomber". North Atlantic Aviation Museum. North Atlantic Aviation Museum. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Restoration". National Air Force Museum of Canada. National Air Force Museum of Canada. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "Featured Aircraft". Air Force Museum of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "AVIATION". Museum of Transport and Technology. MOTAT. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Wesley, Richard (23 December 2007). "Lockheed 414 Hudson GR.III". MOTAT Aircraft Collection. Blogger. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Lockheed Hudson NZ2035". Ferrymead Aeronautical Society. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Airframe Dossier - Lockheed Hudson III, s/n NZ2035 RNZAF, c/n 414-3858". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Homewood, Dave. "Royal New Zealand Air Force Lockheed Hudson Survivors". Wings Over Cambridge. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "RNZAF Lockheed Hudson Mk.III, Mk.IIIA, Mk.V & Mk.VI NZ2001 to NZ2094". NZDF-SERIALS. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Lockheed Hudson IIIA". Royal Air Force Museum. Trustees of the Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Simpson, Andrew (2012). "INDIVIDUAL HISTORY" (PDF). Royal Air Force Museum. Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Cuskelly, Ron (2 March 2016). "VH-AGJ". Adastra Aerial Surveys. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Francillon 1982, pp. 147, 158.

Bibliography[]

- Borth, Christy. Masters of Mass Production. Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1945.

- Douglas, W.A.B. The Creation of a National Air Force. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-80202-584-5.

- Francillon, René J. (1982). Lockheed Aircraft since 1913. London: Putnam & Company. ISBN 0-370-30329-6..

- Francillon, René. Lockheed Aircraft since 1913. London: Putnam, 1987. ISBN 0-85177-805-4.

- Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II. New York: Random House, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- Kightly, James."Database: Lockheed Hudson". Aeroplane, Vol. 43, No. 10, October 2015. pp. 73–88.

- Cortet, Pierre (April 2002). "Des avions alliés aux couleurs japonais" [Allied Aircraft in Japanese Colors]. Avions: Toute l'Aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (109): 17–21. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Marson, Peter J. The Lockheed Twins. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air-Britain (Historians) Ltd, 2001. ISBN 0-85130-284-X.

- Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II. Cypress, California: Amazon Digital Services, Inc., 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- Roba, Jean-Louis & Cony, Christophe (October 2001). "Donnerkeil: 12 février 1942" [Operation Donnerkeil: 12 February 1942]. Avions: Toute l'Aéronautique et son histoire (in French) (103): 25–32. ISSN 1243-8650.

- Stitt, Robert M. (July–August 2002). "Round-out". Air Enthusiast. No. 100. p. 75. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Swanborough, Gordon and Peter M. Bowers. United States Navy Aircraft since 1911. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1976. ISBN 0-87021-792-5.

- Vincent, David. The RAAF Hudson Story: Book One Highbury, South Australia: David Vincent, 1999. ISBN 0-9596052-2-3

- Lake, Alan. Flying Units of the RAF – The ancestry, formation and disbandment of all flying units from 1912. Airlife Publishing Ltd, Shrewsbury, UK, 1999, ISBN 1840370866.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lockheed Hudson. |

- Lockheed aircraft

- 1930s United States patrol aircraft

- Low-wing aircraft

- World War II patrol aircraft of the United States

- Aircraft first flown in 1938

- Twin piston-engined tractor aircraft