B. Hick and Sons

| Type | General partnership |

|---|---|

| Industry | Engineering Heavy industry |

| Predecessor | B. Hick and Son |

| Founded | 10 April 1833[1] |

| Founder | Benjamin Hick |

| Successor | Hick, Hargreaves & Co. Ltd. |

| Headquarters | Soho Iron Works, Crook Street, Bolton , United Kingdom |

Number of locations | 2 |

Key people | John Hargreaves Jr John Hick George Henry Corliss William Hick William Hargreaves William Inglis Robert Luthy Benjamin Hick John Henry Hargreaves Wyndham D'arcy Madden George Arrowsmith |

Number of employees | 1000 (1894)[2] 600 (1961)[3] 350 (1990)[4] |

B. Hick and Sons, subsequently Hick, Hargreaves & Co, was a British engineering company based at the Soho Ironworks in Bolton, England.[5] Benjamin Hick, a partner in Rothwell, Hick and Rothwell, later Rothwell, Hick & Co., set up the company in partnership with two of his sons, John (1815–1894) and Benjamin (1818–1845) in 1833.[6][7]

Benjamin Jr left the company after a year[8] for a partnership in a Liverpool company,[9][10] possibly George Forrester & Co.[11] In 1840 he filed a patent governor[12] for B. Hick and Son using an Egyptian winged motif, that featured on the front page of Mechanics' Magazine.[13]

Hick's youngest son William (1820–1844) served as an apprentice millwright, engineer in the company from 1834 and a 'fitter' from 1837, he was listed as an iron founder in 1843 with his eldest brother John.[14][15][16]

Locomotives[]

The company's first steam locomotive Soho, named after the works was a 0-4-2 goods type, built in 1833[10] for carrier John Hargreaves. In 1834 an unconventional, gear-driven four-wheeled rail carriage was conceived[17] for Bolton solicitor and banker, (1810–1883).[8][18] The engine was the first 3-cylinder locomotive and its design incorporated aerodynamic turned iron wheel rims with plate discs as an alternative to conventional spokes.[19][20] The 3-cylinder concept evolved into Hick's experimental horizontal boiler A 2-2-2 locomotive about 1840, adopting the principle features of the vertical boiler engine.[1][21] The A 2-2-2 design appears not to have been put into production.[22]

Disc wheels and wheel fairings have since been used in Land speed record attempts, early motor racing, armoured cars, aviation, motorcycle speedway, wheelchair racing, icetrack cycling, velomobiles and bicycle racing, particularly track cycling, track bikes and time trials.

Hick's wheel design was used on a number of Great Western Railway engines including what may have been the world's first streamlined locomotive; an experimental prototype, nicknamed Grasshoper, driven by Brunel at 100 miles per hour (160 km/h), c.1847. The 10 ft disc wheels from GWR locomotives Ajax and Hurricane were lent to convey the statue of the Duke of Wellington to Hyde Park Corner[23] in London.

More locomotives were built over the 1830s, some for export to the United States[17] including a 2-2-0 Fulton for the Pontchartrain Railroad in 1834,[24] New Orleans and Carrollton for the St. Charles Streetcar Line in New Orleans in 1835[25] and a second New Orleans for the same line in 1837.[26] A 10 hp stationary engine was supplied to the Carrollton Railroad Company in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, for ironworking purposes, but damaged by fire in 1838.[27] Two 0-4-0 tender locomotives Potomak and Louisa were delivered to the Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad and a third, Virginia to the Raleigh and Gaston Railroad in North Carolina during 1836.[28]

Between 1837 and 1840 the company subcontracted for Edward Bury and Company, supplying engines to the Midland Counties Railway, London and Birmingham Railway, North Union Railway, Manchester and Leeds Railway and indirectly to the Grand Crimean Central Railway via the London and North Western Railway in 1855.[29] Engines were built for the Taff Vale Railway, Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, Cheshire, Lancashire and Birkenhead Railway, Chester and Birkenhead Railway, Eastern Counties Railway, Liverpool and Manchester Railway, North Midland Railway, Paris and Versailles Railway and Bordeaux Railway.[30]

In 1841 the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway successfully used American Norris 4-2-0 locomotives on the notorious Lickey Incline and Hick built three similar locomotives for the line. Between 1844 and 1846 the firm built a number of "long boiler" locomotives with haystack fireboxes and in 1848, four 2-4-0s for the North Staffordshire Railway.[31][32][1][10] In the same year, the company built Chester, probably the earliest known prototype of a 6-wheel coupled 0-6-0} goods locomotive.[9][33]

Engineering drawings[]

Hick Hargreaves early locomotive drawings, 1974.

Hick Hargreaves collection of early locomotive and steam engine drawings[9] represents one of the finest of its kind in the world. The majority were produced by Benjamin Hick senior and John Hick between 1833-1855, they are of significant interest for their technical detail, fine draughtsmanship and artistic merit.[1] The elaborate finish and harmonious colouring extends from the largest drawings for prospective customers to ordinary working drawings and records for the engineer.

Works like this influenced the contemporary illustrators of popular science and technology of the time like John Emslie (1813-1875), their aesthetic quality stems from a romantic outlook in which science and poetry were partners.[34]

The drawings are held by Bolton Metropolitan Borough Archives and the Transport Trust, University of Surrey.[35]

Hick, Hargreaves & Co[]

After the death of Benjamin Hick in 1842, the firm continued as Benjamin Hick & Son under the management of his eldest son, John Hick. In 1845 John took his brother-in-law John Hargreaves Jr (1800–1874)[36] into partnership followed by the younger brother (1821–1889)[36] in 1847.[37][38] John Hargreaves Jr left the firm in April 1850[37][39] before buying Silwood Park in Berkshire.[40]

The following year B. Hick and Son exhibited engineering models and machinery at The Great Exhibition in Class VI. Manufacturing Machines and Tools, including a 6 horse power crank overhead engine and mill-gear driving Hibbert, Platt and Sons' cotton machinery and a 2 hp high-pressure oscillating engine[41] driving a Ryder forging machine.[42] Both engines were modelled in the Egyptian Style.[43][44] The company received a Council Medal award for its mill gearing, radial drill mandrils and portable forges.[45] The B. Hick & Son London office was at 1 New Broad Street in the City.[46][47]

One of the Great Exhibition models, a 1:10 scale 1840 double beam engine built in the Egyptian style for John Marshall's Temple Works in Leeds,[48] is displayed at the Science Museum and considered to be the ultimate development of a Watt engine.[49] A second model, apparently built by John Hick and probably shown at the Great Exhibition, is the open ended 3-cylinder A 2-2-2 locomotive on display at Bolton Museum.[1][21][22][41][48] Bolton Museum holds the best collection of Egyptian cotton products outside the British Museum as a result of the company's strong exports, particularly to Egypt.[50]

Locomotive building continued until 1855,[10] and in all some ninety to a hundred locomotives were produced;[8] but they were a sideline for the company, which concentrated on marine and stationary engines, of which they made a large number.[38]

B. Hick and Son supplied engines for the paddle frigates Afonso by Thomas Royden & Sons[51] and Amazonas by the leading shipbuilder in Liverpool, Thomas Wilson & Co. also builders of the Royal William;[52][53][54] the screw propelled Mediterranean steamers, Nile and Orontes and the SS Don Manuel built by Alexander Denny and Brothers[55][56][57] of Dumbarton.[9][48] The Brazilian Navy's Afonso rescued passengers from the Ocean Monarch in 1848[58] and took part in the Battle of The Tonelero Pass in 1851;[59] the Amazonas participated in the Battle of Riachuelo in 1865.[53]

The company made blowing engines for furnaces and smelters, boilers, weighing machines, water wheels and mill machinery.[2][33] It supplied machinery "on a new and perfectly unique" concept together with iron pillars, roofing and fittings for the steam-driven pulp and paper mill at Woolwich Arsenal in 1856. The mill made cartridge bags at the rate of about 20,000 per hour, sufficient to supply the entire British army and navy. The intention was to manufacture paper for various departments of Her Majesty's service.[60]

Steel boilers were first produced in 1863, mostly of the Lancashire type, and more than 200 locomotive boilers were made for torpedo boats into the 1890s. The Phoenix Boiler Works were purchased in 1891 to meet an increase in demands.[2][9]

The company introduced the highly efficient Corliss valve gear into the United Kingdom from the United States in about 1864 and was closely identified with it thereafter;[2] William Inglis being responsible for promoting the high speed Corliss engine.[8] About 1881 Hick, Hargreaves received orders for two Corliss engines of 3000 hp, the largest cotton mill engines in the world.[61] Hargreaves and Inglis trip gear was first applied to a large single cylinder 1800 hp Corliss engine at Eagley Mills near Bolton and the company received a Gold Medal for its products at the 1885 International Inventions Exhibition.[62] Mill gearing was a speciality including large flywheels for rope drives, one example of 128 tons being 32 ft in diameter and groved for 56 ropes. Turbines and hydraulic machinery were also manufactured. Many of the tools were to suit the specialist work, with travelling cranes to take 15 to 40 tons in weight, a large lathe, side planer, slotting machine, pit planer and a tool for turning four 32 ft rope flywheels simultaneously. The workshops also featured an 80ton hydraulic riveting machine.[2] For the ease of shipping and transportation, Soho Iron Works had its own railway system,[63] traversed by sidings of the London North Western Railway (LNWR).[2][33] Inglis, who lived in Bolton was a neighbour of LNWR's chief mechanical engineer, Francis Webb.[8]

The company was renamed Hick, Hargreaves and Company in 1867;[64] John Hick retired from the business in 1868 when he became a member of parliament (MP),[10][65][33] leaving William Hargreaves as the sole proprietor. On the death of John Hick's nephew Benjamin Hick in 1882, a "much respected member of the firm",[66] active involvement of the Hick family ceased.[67] William Hargreaves died in 1889 and, under the directorship of his three sons, John Henry, Frances and Percy, the business became a private limited company in 1892.[48][65] In 1893 the founder's great grandson, also Benjamin Hick[68] started an apprenticeship,[69] followed by his younger brother Geoffrey[70][71] about 1900.

Diversification[]

About 1885 Hick Hargreaves & Co became associated with Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti during the reconstruction of the Grosvenor Gallery and began to manufacture steam engines for power generation including those of Ferranti's Deptford Power Station,[73] the largest power station in the world at the time.[74]

In 1908 the company was licensed to build uniflow engines. From 1911 the company began the manufacture of large diesel engines, however these did not prove successful and were eventually discontinued. Boiler production finished in 1912. During World War I the company was involved in war work,[50] producing 9.2 inch then 6 inch shells for the Ministry of Munitions, mines[33] and a contract with Vickers to produce marine oil engines for submarines, under licence for the Admiralty.[75]

In the early hours 26 September 1916, the works were targeted by Zeppelin L 21; a bomb missed passing through the roof of nearby Holy Trinity Church.[76]

The company's recoil gear for the Vickers 18 pounder quick firing gun was so successful that by war's end a significant part of the factory was devoted to its production. Civil manufacture was not suspended entirely and in 1916 the firm began making Hick-Bréguet two-stage steam jet air ejectors and high vacuum condensing plant[77][78][79] for power generation, including a contract with Yorkshire Electric Power Company. Hick Hargreaves production greatly expanded as centralised power generation was adopted in Great Britain,[5][50] by the formation of the Central Electricity Board (CEB) in 1926.[75]

In the search for new markets after the war the firm invested in machinery to produce petrol engines and other car components, entering a contract with Vulcan Motor & Engineering Co of Southport for 1000 20 hp petrol engines, but work discontinued in 1922 when Vulcan became bankrupt, with only 150 completed.[33]

Following the arrival of electrical engineer Wyndham D'arcy Madden from Stothert & Pitt in 1919, Hick Hargreaves was re-organised to include a sales department responsible for advertising, supervised by Madden who in succession was appointed Managing Director in 1922, serving until 1963.[80]

Trained at Faraday House Engineering College, from outside the Hargreaves family circle and established conventions of the industrial regions, Madden ensured the business was run economically during the difficult times ahead. The readiness to adapt was crucial to success during the interwar period; he realised that marketing the firm's specialities was as important to the design and manufacture of its products.[81]

As the steam turbine replaced reciprocating steam engines, the company required a skilled engineer to produce a design of its own; in 1923 former principle assistant to the Chief Turbine Designer of English Electric, George Arrowsmith was appointed as Hick Hargreaves' Chief Turbine Designer; development continued and by 1927 the firm's engine work was principally steam turbines for electricity generating stations, becoming a major supplier to the CEB.[75] Three of the nine turbines produced were supplied to Fraser & Chalmers for installation at Ham Halls power station. Arrowsmith was appointed Chief Engineer and a director of Hick Hargreaves in 1928.[82]

During the 1930s, the company acquired the records, drawings and patterns of four defunct steam engine manufacturers: J & E Wood, John Musgrave & Sons Limited, Galloways Limited and Scott & Hodgson Limited. As a consequence it made a lucrative business out of repairs and the supply of spare parts during the Great Depression.[5][75][33] Large stationary steam engines were still used for the many cotton mills in the Bolton area until the collapse of the industry after World War II.[50]

3 and 4-cylinder triple expansion marine steam engines were built during the 1940s,[83][84][85][86] post-war the company expanded its work in electricity generation, again becoming a major supplier to the CEB and branched out into food processing, oil refining and offshore oil equipment production,[87] continuing to supply vacuum equipment to the chemical and petrochemical industries.

By the early 1960's Hick Hargreaves established itself in the practical application of nuclear energy, supplying de-aerating equipment for the early atomic power stations at Calder Hall, Chapelcross and Dounreay, and the complete feed heating system, condensing plant and steam dump condensers for Hunterston. The company received orders for the ejectors, de-aerators and dump condensers for the prototype advanced gas cooled reactor at Windscale[87] and a commission to design the condensing plants and feed systems for the first 175.000 KW Japanese Atomic Power Station at Tokai Mura.[88][63]

About 1969 the firm's 1930s corporate identity[89] was brought up to date with a logo, while Madden's established and successful marketing of specialities continued;[88][90][63] during 1974 Hick Hargreaves promoted its achievements and support of industrial archaeology with an exhibition of B. Hick and Son locomotive drawings, emphasising its response to changing industrial developments since the nineteenth century.[88][1]

In 2000 Hick Hargreaves' products included compressors, industrial blowers, refrigeration equipment and liquid ring motors.[33]

Soho Iron Works[]

Between the 1840s and 1870s, the firm had its own Brass Band, "John Hick's Esq, Band," known as the Soho Iron Works Band with a uniform of "... rich full braided coat, black trousers, with two-inch gold lace down the sides and blue cap with gold band," who would play airs through the streets of Bolton.[91]

Gold Medal certificate awarded to Hick, Hargreaves and Co. at the International Inventions Exhibition 1885 for their Corliss engine supplementary governor & automatic barring engine. signed by the Prince of Wales and Frederick Bramwell.

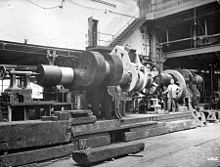

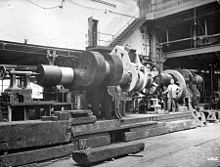

Finishing the ends of a crankshaft after building;[97] an improvised lathe for machining a large steam engine crankshaft, 1900[63] with a worm and wheel for turning the shaft in the centre. In the background on the far right is a screw cutting machine.[98]

Lancashire boiler 1900, painted with a protective coating, the mountings such as safety valves, stop valve, feed check valves and water level gauges, have been removed.[98]

Flywheel for a large textile mill engine 1900, set up to machine grooves for the rope drives simultaneously. The saddle with two tool posts to the front. The wheel is rotated by two pinions driving via the cast-in barring gear teeth in the flywheel rim. Temporary wedges are securing the spokes to the hub of the wheel. A travelling crane behind and above.[63][98]

Cross compound Corliss mill engine 1900, shop assembled to ensure that the parts fit together and make any preliminary adjustments, the low-pressure cylinder is on the left, high-pressure cylinder on the right.[63][98]

Flywheel; the hub and spokes cast in two halves, bolted at the hub with the rim assembled from ten castings. These are bolted to the spokes, held together by shrinking rings in the grooves.[63]

Small steam hammer 1900,[98] with line shafting and belt drives to the rear.

Superheater of a Lancashire boiler 1900, for the extraction of heat from waste gasses, and transfer of heat to saturated steam passing from the boiler to the steam range or engine. This raised the overall thermal efficiency of the plant, and would also prevent damage from slugs of condensate by ensuring the saturated steam was dry and not wet.[98]

From The Engineer, a 400 hp 4-cylinder Hick Hargreaves & Co. Ltd. stationary Diesel engine under test, destined for Guayaquil, South America, 1920.[99]

Certificate issued by The Ministry of Labour for The National Scheme for the Employment of Disabled Men, recognising the membership of Hick Hargreaves and Co. Ltd. Signed by Thomas James Macnamara, Minister of Labour 1920–1922.

Ownership changes[]

In 1968 the Hargreaves family sold the company to Electrical & Industrial Securities Ltd. In 2001, the firm was bought by The BOC Group from Smiths Industries. Lower costs in Eastern Europe proved attractive, so production at the Soho Foundry was wound down and machinery transferred to Czechoslovakia. The historic records, including drawings and photographs, were deposited with Bolton library.[33] Hick, Hargreaves was the most enduring engineering company in Bolton and Britain, surviving 170 years from the outset.[33][100]

Smiths had already sold the site to J Sainsbury plc and, despite being marked by a blue plaque, Soho Iron Works were closed 23 August 2002[101] and demolished entirely about November that year[102] in favour of a car park, petrol station and Sainsbury's supermarket,[33] opening 27 March 2003.[103]

The residue of the company relocated to a redundant Post Office building, on Wingates Industrial Estate, Westhoughton. The red highlights were overpainted in light blue and a luxurious reception area installed. Behind this reception there was little more than a modern design office and large parts store. All manufacturing had ceased. Several years later, this building was vacated too. A much reduced design office relocated to just half of the upper floor of an office block on Lynstock Way, Lostock, under the Edwards Limited name (see below.)

Two switchgear panels, the works clock and symbolic cast iron gateposts with Hick's caduceus logo were saved by the Northern Mill Engine Society.[33][104]

The BOC Group plc was later taken over by Linde A.G. of Germany, who intended to return the combined group to a 'pure gas' business. It sold off the BOC Edwards engineering division,[105] into which Hick Hargreaves of Bolton had been placed and combined with the Edwards High Vacuum business of BOC Edwards based at Crawley, West Sussex. The business of the vacuum company was sold to private shareholders CCMP Capital and on 1 June 2007 was re-established as an independent UK private limited company "Edwards Limited".

The Bolton site of [106] is now a design shop with outsourced UK and foreign manufacture and has moved to new office premises in Lostock, where it continues to sell some steam ejector, feed heater and deaeration technology of the old Hick Hargreaves business as a part of Edwards Limited.[107]

Mills powered by Hick, Hargreaves engines[]

- Textile Mill, Chadderton

- Cavendish Mill, Ashton-under-Lyne

- Century Mill, Farnworth

- Pioneer Mill, Radcliffe[108]

See also[]

- Bradford Colliery

- James Cudworth

- Fred Dibnah

- Dick, Kerr & Co. - Hick Hargreaves condenser for an English Electric turbo generator[109]

- Helmshore Mills Textile Museum

- House-built engine

- Redevelopment of Mumbai mills[110]

- Thomas Pitfield - apprenticed to Hick Hargreaves[111]

- Vickers Armstrongs - vacuum pumps for the Barnes Wallis Stratosphere at Brooklands[112][113][114]

- Wadia Group[110]

- Waltham Abbey Royal Gunpowder Mills[115]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Skeat, W. O.; Marshall, John (1974). Catalogue: Hick Hargreaves Exhibition of early locomotive drawings. Rockliff Bros. Ltd., Long Lane, Liverpool L9 7BE.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Messrs. Hick, Hargreaves and Co., Soho Iron Works, and Phoenix Boiler Works, Bolton". Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: 454–455. July 1894.

- ^ "Hick, Hargreaves and Co". Grace's Guide. Grace's Guide Ltd. 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

600 employees.

- ^ Untitled typescript (1990). "Historical Notes". Annual Report and Accounts (FT Annual Reports Service ed.). Hick, Hargreaves and Company, Bolton; EIS Group plc.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pilling (1985), p. 20.

- ^ Marshall (1978), pp. 112–113.

- ^ Redfern, Diane. "Benjamin Hick". Diane Redfern Ancestry & Family History. © 2009-2013 dianeredfern.ca. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Jones, Kevin Philip (30 March 2016). "British locomotive manufacturers". Steamindex. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Ahrons, Ernest Leopold. "Short Histories of Famous Firms, Messrs. Hick, Hargreaves and Co., Reprint from The Engineer, 25 June – 30 July 1920". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Marshall (1978), p. 113.

- ^ "MacGregor, Horsfall, Hick". Liverpool & South West Lancs Genealogy. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Bennett, Stuart (1986). A History of Control Engineering, 1800-1930 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). IET. ISBN 0863410472.

- ^ Robertson, J.C., ed. (15 May 1841). "Hick's Patent Governor for Steam-Engines and Water Wheels". The Mechanics' Magazine, Museum, Register, Journal, and Gazette. 34. pp. 369–372.

- ^ Slater's Directory 1843 - Bolton. Isaac Slater. 1843.

- ^ Pilling (1985), p. 475.

- ^ Redfern, Diane. "William Hick". Diane Redfern Ancestry & Family History. © 2009-2013 dianeredfern.ca. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Timmins (1998), pp. 222–223.

- ^ "Thomas Lever Rushton". Links in a Chain – the Mayors of Bolton. Bolton Council. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ Hick, Benjamin (1836). Newton, William (ed.). "for improvements in locomotive steam-carriages". Newton's London Journal of Arts and Sciences. Conjoined. VII: 265–271. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ Hebert, Luke (1836). The Engineer's and Mechanic's Encyclopædia. II. Thomas Kelly. pp. 568–569. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Townend, Peter (March 2016). "The first three cylinder locomotive". Steamindex. 5 (50).

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Bolton Museum caption". flikcr. Bolton Museum. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

Model of an experimental locomotive, about 1840

- ^ Speller, John. "Ajax & Mars". John Speller's Web Pages - GWR Broad Gauge: Locomotives. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ Guilbeau, James (2011) [1975]. St. Charles Streetcar, The: Or, the New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad. Louisiana Landmarks (illustrated ed.). Pelican Publishing Company. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-879714-02-1.

- ^ Guilbeau (1975), p. 12.

- ^ American Society of Mechanical Engineers Regional Transit Authority. "St. Charles Avenue Streetcar Line, 1835" (PDF). Adapted from Guilbeau (1975), revised and reprinted 1977. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers 345 East 47th Street New York, N.Y. 10017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ United States Dept. of the Treasury (1838). Steam Engines: Letter from the Secretary of the Treasury. p. 306.

- ^ Hall; Smith, A. Rupert; Norman (1981). "Manchester: Sharp Roberts & Co.". History of Technology, Volume 6 (electronic ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781350018006. Retrieved 9 November 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Cooke, Brian (1997). The Grand Crimean Central Railway (Second edition, revised and expanded. ed.). Cavalier House, Knutsford. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-0951588918.

- ^ Mackenzie, William (2000). Brooke, David (ed.). The Diary of William Mackenzie, the First International Railway Contractor. Thomas Telford. p. 388. ISBN 978-0727728302. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ Saul (1968), pp. 186–222.

- ^ Christiansen & Miller (1971), p. 309.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Lewis, David (2003). Nevell, Dr. Michael (ed.). "Hick, Hargreaves & Co, Engineers, Soho Foundry, Bolton, 1833–2002". Industrial Archaeology Northwest. 1 (3): 18–20. ISSN 1479-5345.

- ^ Klingender, Francis Donald (1968). "Documentary Illustration". In Elton, Arthur (ed.). Art and the Industrial Revolution (illustrated, revised ed.). University of Michigan: Augustus M. Kelley. pp. 76–77.

- ^ "Hick Hargreaves & Co.Ltd, Engineers and Millwrights, Soho Works, Bolton". The National Archives. Gov.uk. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marshall (1978), p. 104.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "NOTICE" (PDF). The London Gazette (21195): 874. 28 March 1851. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "1833 to 1933 at the Soho Iron Works Bolton". Centenary Pamphlet Published by the Firm.

- ^ Pilling (1985), p. 102.

- ^ "A Short History of Silwood Park Sunninghill". Sunninghill Berkshire England. The Great Park Portal. 2008. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

1854: John Hargreaves, Jnr. purchased at least part of the estate from Mrs Forbes (widow of M Forbes) for £30,000

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Hick, B., & Son". Great Exhibition 1851. Official, Descriptive and Illustrated catalogue Part II. Classes V. to X. 1851. p. 293. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "Hick, B., & Son". Great Exhibition 1851. Official, Descriptive and Illustrated catalogue Part II. Classes V. to X. 1851. p. 294. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "B. Hick & Son - Crank Overhead Engine - Drawings & Photos". Hemingway Kits. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "B. Hick & Son - Oscillating Engine". Hemingway Kits. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "1851 Great Exhibition: Reports of the Juries: Class VI". Grace's Guide. Grace's Guide Ltd. 1852. pp. 203–204. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "Street Directory". UK City and County Directories 1600s -1900s. 1851. p. 395. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ^ "Commercial Directory". UK City and County Directories 1600s -1900s. 1851. p. 791. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b c d A.W.M (16 April 1936). "Models of a Beam Engine and Steam Turbine". Model Engineer. Vol. 74 no. 1823. pp. 79–80.

- ^ Science Museum caption. Energy Hall: Science Museum.

Model represents the ultimate development of Boulton & Watt's steam engine. By the time the engine was displayed at the 1851 Great Exhibition, Britain used half as much steam power again as the whole of western Europe.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Collenette, Sam (June 2012). "From Bolton to Warwick". Warwickshire Industrial Archaeology Society Newsletter (45): 3.

- ^ "Dom Afonso". Brasil Mergulho. Brasil Mergulho. 25 June 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ Aspinall, Henry Kelsall (1903). "Shipbuilding in Liverpool". Birkenhead and Its Surroundings. Рипол Классик. p. 307. ISBN 9785874616144. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

the leading shipbuilder in Liverpool was Thomas Wilson

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fragata a Vapor Amazonas". Navios De Guerra Brasileiros. 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ Swiggum and Kohli, S. and M. (1997–2016). "Royal William of 1838". TheShipsList. TheShipsList - (Swiggum). Retrieved 19 October 2016.

built by Wilson & Co.

- ^ "Nile". The Clyde Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "ORONTES". The Clyde Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "Don Manuel". The Clyde Built Ships. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "Burning of the Ocean Monarch". The Times (19952). 26 August 1848. p. 5.

- ^ "Fragata a Vapor Afonso". Navios De Guerra Brasileiros. 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ "Military and Naval Intelligence". The Times (22460). 30 August 1856. p. 10:col A.

- ^ "One Thousand Horse-Power Corliss Engine". Scientific American Supplement. XI (286). 25 June 1881. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

and they have an order for a pair of horizontal compound Corliss engines intended to indicate 3,000 horse-power. These engines will be the largest cotton mill engines in the world.

- ^ "Messrs. Hick, Hargreaves and Co.'s Horizontal Engine". The Engineer: 61. 22 January 1886.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j "Hick, Hargreaves and Co". Grace's Guide. Grace's Guide Ltd. 29 August 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ Who's Who in Business. Whitaker's. 1914. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pilling (1985), pp. XI, 118–119, 158, 193, 539–541.

- ^ Clegg, James (1888). Annals of Bolton, History, Chronology, Politics, Parliamentary and Municipal Polls. Bolton: The Chronicle Office, Knowlsey Street. Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center. p. 199. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pilling (1985), p. 452.

- ^ Redfern, Diane. "Benjamin Hick". Diane Redfern Ancestry & Family History. © 2009-2013 dianeredfern.ca. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ Membership records. Institute of Mechanical Engineers.

- ^ "Navy List 1908 Ship M to P". WORLD NAVAL SHIPS.COM. Cranston Fine Arts. 1908. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

Mars (Home Fleet), 14.900 tons, H.P. 10,000

- ^ Redfern, Diane. "Geoffrey Hick". Diane Redfern Ancestry & Family History. © 2009-2013 dianeredfern.ca. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ Walford, Edward (1876). The county families of the United Kingdom; or, Royal manual of the titled and untitled aristocracy of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center: R. Hardwicke. p. 457. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Wilson (2001), p. 182.

- ^ Wilson, J. F. (1988). "The Deptford experience". Ferranti and the British Electrical Industry, 1864-1930 (illustrated, reprint ed.). Manchester University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0719023699. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Halton (2001), p. 25.

- ^ Hamer, Phil (November 2011). Jackson, Terence (ed.). "Zeppelin Over Bolton" (PDF). Up the Line: 2. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "La Condensation par Mélange et par Surface et L'éjectair Breguet" (PDF). Maison Breguet. 1915. Retrieved 6 January 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Hick Hargreaves and Co". Grace's Guide. Grace's Guide Ltd. 1921. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Duvéré, Sébastien (2014). "Bréguet, un Tournant vers L'avenir" (PDF). Usine de Déville-lès-Rouen, 160 Ans d'Histoire Industrielle: 8–9. Retrieved 6 January 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Pilling (1985), pp. 273, 284.

- ^ Pilling (1985), pp. IX, 273, 275, 403, 456, 459.

- ^ Pilling (1985), p. 278.

- ^ "Empire Ridley(1941)". Clydebuilt Ships Database. Shipping & Shipbuilding Research Trust. Archived from the original on 30 April 2005. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

Built: 1941

CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Empire Grey". Tyne Built Ships. Shipping & Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

Completed: 05/1944

- ^ "L S T 3001". Tyne Built Ships. Shipping & Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

Completed: 29/06/1945

- ^ "Zarian". Tyne Built Ships. Shipping & Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

Completed: 12/1947

- ^ Jump up to: a b Halton (2001), p. 40.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ed. J. Burrow & Co. Ltd, ed. (1961). The Book of Bolton. Ed. J. Burrow & Co. Ltd., Cheltenham and London. pp. 104–105.

- ^ "Condensing Plant and auxilliaries from Turbine Exhaust to Boiler Check Valves". The Engineer: 39. 5 February 1937.

- ^ Pilling (1985), pp. 273, 275, 284.

- ^ Holman, Gavin. "Extinct Brass Bands (S-Z)". ibew (Internet Bandsman's Everything Within). Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ "Soho Ironworks 1". Bolton Library and Museum Services. Bolton Library and Museum Service. 1888. Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ Deptford 1889-1912. 30 July 1912. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

Comparison of 10,000hp Steam Generators -1889 & 1912-

- ^ Wilson, J. F. (1988). "The Deptford experience". Ferranti and the British Electrical Industry, 1864-1930 (illustrated, reprint ed.). Manchester University Press. pp. 35, 41, 45. ISBN 978-0719023699. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ "Ferranti's Deptford Power Station". Histelec News. South Western Electricity History Society. December 2003. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ "Thread: Galloways rolling mill engines". Practical Machineist.Com. Practicalmachinist.com. 2 January 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ Roscoe, Ian. "Historic Pictures". End of an Era 1832–2002. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Hick Hargreaves & Co. Ltd". history world. historyworld.co.uk. 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ "400 Horse-Power Diesel Engine". The Engineer: 210. 27 August 1920.

- ^ Halton, Maurice J. (14 November 2002). "Firm is moving after 170 years". The Bolton News. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Roscoe, Ian. "Hick Hargreaves Present Day". End of an Era 1832–2002. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ^ "Hick Hargreaves demolition, Bolton". flickr. 11 November 2002. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "New store opens in a flash". The Bolton News. 26 March 2003. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Rowe, Joanne (4 September 2002). "Society saves a piece of history". The Bolton News. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ Linde sells BOC Edwards Archived 20 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Where We Operate". Edwards Vacuum. Edwards Limited. 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ "Chemical & Process Industries". Edwards Vacuum. Edwards Limited. 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ "HRS 2945B Pioneer mill engines Radcliffe". Heritage Photo Archive & Heritage Image Register. Heritage Photo Archive & Heritage Image Register. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ "Electricity generator". MOSI - Museum of Science & Industry. Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester. 2007. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lalvani, Kartar (10 March 2016). "16, The Textile and Jute Industries". The Making of India: The Untold Story of British Enterprise. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 326–336. ISBN 978-1472924841. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Turner, John (2000). "Thomas Baron Pitfield 1903–1999". About Our Composers. The Musical Times. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ Hick, Hargreaves & Co. Ltd. Vacuum pump. Brooklands Museum (Stratosphere).

TYPE RV 17, No. 2386, 1700 C.F.M., 25" VACUUM, 485 R.P.M., 82 B.H.P.

- ^ Brooklands Museum caption. Brooklands Museum (Stratosphere).

THE PLANT ROOM: ...The Plant Room contained a number of vacuum pumps to replicate the low pressure at high altitude by sucking air out of the Chamber,...

- ^ "The Stratosphere Chamber". Brooklands Museum. Brooklands Museum Trust Ltd. 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ Crocker, Allan (16 February 1995). "Meeting at Fort Nelson, Portsdown Hill" (PDF). Gun Powder Mills Study Group: 17–18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Bibliography[]

- Ashmore, Owen (1969). Industrial Archaeology of Lancashire. Newton Abbot: David and Charles.

- Christiansen, Rex & Miller, Robert William (1971). The North Staffordshire Railway. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-5121-5.

- Halton, Maurice J. (September 2001). The Impact of Conflict and Political Change on Northern Industrial Towns, 1890 to 1990 (PDF) (MA Dissertation). Faculty of Humanities and Social Science, Manchester Metropolitan University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2017.

- Lowe, J.W. (1989). British Steam Locomotive Builders. Guild Publishing.

- Mathias, Peter (1983). The First Industrial Nation, An Economic History of Britain 1700–1914 (Third ed.). London: Methuen.

- Pilling, P.W. (1985). Hick Hargreaves and Co., The History of an Engineering Firm c. 1833 – 1939, a Study with Special Reference to Technological Change and Markets (Unpublished Doctoral Thesis). University of Liverpool.

- Saul, S.B. (1968). "The Engineering Industry". In Aldcroft, Derek H. (ed.). The Development of British Industry and Foreign Competition, 1875 – 1914. London: George Allen and Unwin. pp. 186–222.

- Saul, S. B. (1977). Supple, Barry (ed.). The Mechanical Engineering Industries in Britain, 1860 – 1914. Essays in British Business History. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Marshall, John (1978). "John and William Hargreaves, Benjamin and John Hick". A Biographical Dictionary of Railway Engineers. pp. 104, 112–3.

- Singer, Charles, ed. (1958). A History of Technology. 5. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Singleton, John (1991). Lancashire on the Scrapheap, The Cotton Industry 1945–1970. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Timmins, Geoffrey (1998). Made in Lancashire, A History of Regional Industrialisation. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- University of Manchester (1932). An Industrial Survey of the Lancashire Area (Excluding Merseyside). London: HMSO.

- Wilson, John F. (2001). Ferranti: A History, Building a Family Business, 1882–1975. Lancaster: Carnegie.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to B. Hick and Sons. |

- Armley Mills Museum Benjamin Hick and Son beam engine in the Egyptian style c.1845, used for hoisting machinery at the London Road warehouse of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway

- Golburn Historic Waterworks Museum: B. Hick and Son horizontal Corliss engine built for Bell's Creek gold mine, Araluan, New South Wales 1866

- Forncett Industrial Steam Museum: Hick, Hargreaves and Co. 50 hp Corliss girder bed engine 1873 (No.303), used to power Gamble's lace factory, Nottingham

- Chauntry Mills, Haverhill: Hick, Hargreaves and Co. 120 hp non-condensing Corliss engine Caroline 1879, installed at Gurteen's textile manufactorary

- Bolton Town Centre: Hick, Hargreaves and Co. Corliss engine 1886 preserved at Bolton, used to run Ford Ayrton and Co.'s spinning mill at Bentham until 1966

- Lucien Alphonse Legros - eldest son of Alphonse Legros, entered Hick, Hargreaves works in 1887.

- Bolton Steam Museum: Hick, Hargreaves and Co. Ltd. Lancashire boiler front-plate 1906, previously installed at Halliwell Mills, Bolton

- The Clyde Built Ships: Empire Ridley 1941 (Ministry of War Transport), HMS Latimer 1943 (Petroleum Warfare Department)

- Tyne built ships: Empire Grey 1944 (Ministry of War Transport)

- Tyne built ships: Landing Ship, Tank (LST) 3001 1945 (Royal Navy)

- Frederick Glover LST (3): 1946 (War Office), 1952 (Atlantic Steam Navigation Company)

- Tyne built ships: Zarian 1947 (United Africa Company)

- Edwards Limited

- Manufacturing companies established in 1833

- British companies established in 1833

- 1833 establishments in England

- Engineering companies of the United Kingdom

- Engineering companies of England

- Engine manufacturers of the United Kingdom

- Boilermakers

- Millwrights

- Locomotive manufacturers of the United Kingdom

- Steam engine manufacturers

- Machine tool builders

- Electrical engineering companies

- Nuclear technology companies of the United Kingdom

- Companies based in Bolton

- History of Bolton

- Industrial Revolution