Bamileke people

Pe me leke | |

|---|---|

King of Bandjoun, one of the numerous Bamileke Kingdoms in Cameroon | |

| Total population | |

| 2,200,000 [1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,791,000 est. [2][1] | |

| Diaspora | 210,000 est. [3] |

| Languages | |

| Bamileke Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Bamileke Religion, Christianity, Islam, | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

other Grassfields peoples

Baleng | |

The Bamileke are a Grassfields ethnic group that make up 40% of Cameroon's population and inhabit the country's western region. The Bamileke are subdivided into several tribes, each under the guidance of a King or fon. They speak a number of related languages from the Eastern Grassfields branch of the Grassfields language family

This article may be unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. (September 2021) |

These languages are not closely related, cameroon are languages from all side of Africa with more than 300 languages from Bantu to nihilotic. The Bamileke people are known for their very striking and often intricately beaded masquerade art, including the elephacats[clarification needed]. The Bamileke people are also known[by whom?] for their entrepreneurship and hold significant economic power in Cameroon.

This article may be unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. (September 2021) |

Organization[]

The Bamileke are organized under several chiefdoms (or fondoms). Of these, the fondoms of Bafang, Bafoussam, Bandjoun, Baham, Bangangté, , Dschang, and Mbouda are the most prominent. The Bamileke also share much history and culture with the neighboring fondoms of the Northwest region and notably the Lebialem region of the Southwest region, but the groups have been divided since their territories were split between the French and English in colonial times.

Languages[]

Following ethnographic classification, we can identify 11 different languages or dialects:

Variants of Ghomala' are spoken in most of the Mifi, Koung-Khi, Hauts-Plateaux departments, the eastern Menoua, and portions of Bamboutos, by 260,00 people (1982, SIL). The main fondoms are Baham, Bafoussam, Bamendjou, Bandjoun.

Towards southwest is spoken Fe'fe' in the Upper Nkam division. The main towns include Bafang, Baku, and Kékem.

Nda'nda' is spoken in the western third of the Ndé division. The major settlement is at Bazou.

Yemba is spoken by 300,000 or more people in 1992. Their lands span most of the Menoua division to the west of the Bandjoun, with their capital at Dschang. Fokoué is another major settlement.

Medumba is spoken in most of the Ndé division, by 210,000 people in 1991, with major settlements at Bangangté and Tonga.

Mengaka, Ngiemboon, Ngomba and Ngombale are spoken in Mbouda.

Kwa is spoken between the Ndé and the Littoral region, Ngwe around Fontem in the Southwest region, and Mmuock (language) by the Mmuock people in the Lebialem division of the Southwest region.

Bamileke belongs to the Mbam-Nkam group of Grassfields languages

History[]

The Bamilekes' origins are uncertain.[2] They migrated to what is now northern Cameroon between the 11th and 14th centuries. In the 17th century they migrated further south and west under the pressure of the Fulani.[3] Today, a majority of this ethnic group are Christians, and it is estimated that almost half of Bamileke people are English speaking. There are 123 Bamileke groupings with 6 in the southwest and 106 in the western region. Apart from the Bamileke, there are other tribes that are historically more or less linked to the Bamileke, whether by blood or through certain cultural intercourse,[4] as well as recently settled foreigners (Fulani, Hausa, Igbo, etc.).

During the mid-17th century, the Tikar people left the North to avoid forced conversion to Islam. They migrated as far south as Foumban. Conquerors came all the way to Foumban to try to impose Islam on them. A war began, pushing some people to leave while others remained, submitting to Islam. This marks the division between the Bamun and Bafia people.

In the 17th century they migrated further south and west to avoid being forced to convert to Islam. Another reason for migration was to resist enslavement during the Atlantic Slave Trade.

German administration[]

Germany gained control of "Kamerun" in 1884.

The Germans first applied the term "Bamileke" to the people as administrative shorthand for the people of the region.

French administration and post-independence[]

The Bamileke are very dynamic and have a great sense of entrepreneurship. Thus, they can be found in almost all regions of Cameroon, mainly as business owners.

In 1955, the colonial French power banned the Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC) political party, which was pushing for Cameroonian independence. Following that, the French started an offensive against UPC militants. Much of the fighting occurred in the western region inhabited by Bamileke. Some tens of thousands of people died in the UPC conflict with French and Cameroonian troops.[5][6][7]

Lifestyle and settlement patterns[]

Political structure and agriculture[]

Bamileke settlements follow a well-organized and structured pattern. Houses of family members are often grouped together and surrounded by small fields. Men typically clear the fields, but it is largely women who work them. Most work is done with tools such as machetes and hoes. Staple crops include cocoyams, groundnuts and maize.

Bamileke settlements are organized as chiefdoms. The chief, or fon or fong is considered as the spiritual, political, judicial and military leader. The chief is also considered as the 'father' of the chiefdom. He thus has great respect from the population. The successor of the 'father' is chosen among his children. The successor's identity is typically kept secret until the fon's death.

The fon has typically 9 ministers and several other advisers and councils. The ministers are in charge of the crowning of the new fon. The council of ministers, also known as the Council of Notables is called Kamveu. In addition, a "queen mother" or mafo was an important figure for some fons in the past. Below the fon and his advisers lie a number of ward heads, each responsible for a particular portion of the village. Some Bamileke groups also recognize sub-chiefs, or fonte.

Economic activities[]

Traditional homes are constructed by first erecting a raffia-pole frame into four square walls. Builders then stuff the resulting holes with grass and cover the whole building with mud. The thatched roof is typically shaped into a tall cone. Nowadays, however, this type of construction is mostly reserved for barns, storage buildings, and gathering places for various traditional secret societies. Instead, modern Bamileke homes are made of bricks of either sun-dried mud or of concrete. Roofs are of metal sheeting.

Religious beliefs[]

During the colonial period, parts of the Bamileke region adopted Christianity. Some of them practice Islam, particularly toward the border with the Tikar and the Bamun. The Bamileke are known for elaborate elephant masks used for dance ceremonies or funerals.[citation needed]

Royal Tradition and the Arts[]

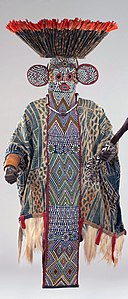

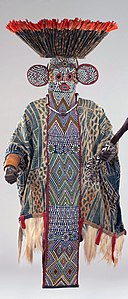

Masquerades are an integral part of Bamileke culture and expression. Colorful, beaded masks are donned at special events such as funerals, important palace festivals and other royal ceremonies. The masks are performed by men and aim to support and enforce royal authority.[8]

The power of a Bamileke king, called a Fon, is often represented by the elephant, buffalo and leopard. Oral traditions proclaim that the Fon may transform into either an elephant or leopard whenever he chooses. An elephant mask, called a mbap mteng has protruding circular ears, a human like face, and decorative panels on the front and back that hang down to the knees and are covered overall in beautiful geometric beadwork, including much triangular imagery. Isosceles triangles are prevalent as they are the known symbol of the leopard.[9] Beadwork, shells, bronze and other precious embellishments on masks elevate the mask's status.[8] On occasion, a Fon may permit members of the community to perform an elephant mask along with a leopard skin, indicating a statement of wealth, status and power being associated with this masquerade.[9]

Buffalo masks are also very popular and present at most functions throughout Grassland societies, including the Bamileke. They represent power, strength and bravery, and may also be associated with the Fon.[10]

Beadwork[]

Beadwork is an essential element of Bamileke Art and what distinguishes them from other regions of Africa. It is an art form that is highly personal in that no two pieces are alike and are often used in dazzling colors that catch the eye. They may be an indication of status based on what kinds of beads are used. Beadwork utilized all over on wooden sculptures is a technique that is unique only to the Cameroon grasslands.[11]

Before they were colonized, popular beads were obtained from Sub-Saharan countries like Nigeria and were made of shells, nuts, wood, seeds, ceramic, ivory, animal bone and metal. Colonization and trade routes with other countries in Europe and the Middle East introduced brightly colored glass beads as well as pearls, coral and rare stones like emeralds. These came at a price, however. There were often agreements with these other countries to exchange these precious luxury commodities for slaves, gold, oil, ivory and some types of fine woods.[11]

Succession and kinship patterns[]

The Bamileke trace their ancestry, inheritance and succession through the male line, and children belong to the fondom of their father. After a man's death, all of his possessions typically go to a single, male heir. Polygamy (more specifically, polygyny) is practiced, and some important individuals may have literally hundreds of wives. Marriages typically involve a bride price to be paid to the bride's family.

It is argued that the Bamileke inheritance customs contributed to their success in the modern world:

"Succession and inheritance rules are determined by the principle of patrilineal descent. According to custom, the eldest son is the probable heir, but a father may choose any one of his sons to succeed him. An heir takes his dead father's name and inherits any titles held by the latter, including the right to membership in any societies to which he belonged. And, until the mid-1960s, when the law governing polygamy was changed, the heir also inherited his father's wives--a considerable economic responsibility. The rights in land held by the deceased were conferred upon the heir subject to the approval of the chief, and, in the event of financial inheritance, the heir was not obliged to share this with other family members. The ramifications of this are significant. First, dispossessed family members were not automatically entitled to live off the wealth of the heir. Siblings who did not share in the inheritance were, therefore, strongly encouraged to make it on their own through individual initiative and by assuming responsibility for earning their livelihood. Second, this practice of individual responsibility in contrast to a system of strong family obligations prevented a drain on individual financial resources. Rather than spend all of the inheritance maintaining unproductive family members, the heir could, in the contemporary period, utilize his resources in more financially productive ways such as for savings and investment. [...] Finally, the system of inheritance, along with the large-scale migration resulting from population density and land pressures, is one of the internal incentives that accounts for Bamileke success in the nontraditional world".[12]

Donald L. Horowitz also attributes the economic success of the Bamileke to their inheritance customs, arguing that it encouraged younger sons to seek their own living abroad. He wrote in Ethnic groups in conflict: "Primogeniture among the Bamileke and matrilineal inheritance among the Minangkabau of Indonesia have contributed powerfully to the propensity of males from both groups to migrate out of their home region in search of opportunity".[13]

Notable Individuals[]

The Bamileke people have contributed enormously to the development of Cameroon and the world in general. From science to arts, politics, media, sports and much more. Here is an inexhaustible list of notable Bamileke or people of Bamileke descent.

- Maurice Kamto, Former president of the UN International Law Commission, international lawyer, professor[14]

- Paul Kammogne, industrialist and philanthropist[15]

- Victor Fotso, industrialist, philanthropist and billionaire[16]

- Sam Fan Thomas, most popular Makossa musician of the 80s[17]

- Ernest Ouandié, Cameroon's notable independence fighter[18]

- Kadji Defosso, industrialist, philanthropist and billionaire[19]

- Mathias Djoumessi, 1st president of the UPC political party. The party that will bring about independence in Cameroon[20]

- Wilgory Tanjong, Entrepreneur, Social justice activist, and Author[21]

Gallery[]

Stool used by notables of the Fon's (kings) of the Bamileke court

Elaborate Mask Ensemble of the Kuosi Society

Traditional Bamileke architecture, depicting impressive wooden structures. Remnants of Bamileke civilisation

Traditional Bamileke architecture, the Bandjoun palace

A modern building replicating portions of Bamileke architecture. Zingana Hotel, Bafoussam

Young men wearing traditional Bamileke attire during a marriage ceremony

Bamileke Dance Groups

"Clan Age" dance

References[]

- ^ "Bantu, Cameroon-Bamileke". Joshua Project. Retrieved 7 February 2019. Includes other non-Bamileke Semi-Bantu people.

- ^ "Bamileke | people".

- ^ "Bamileke | people".

- ^ Toukam, Dieudonné (2016). Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké. Paris: Editions L'Harmattan. ISBN 9782343087115.

- ^ The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Africa (1981)

- ^ "WHPSI": The World Handbook of Political and Social Indicators by Charles Lewis Taylor

- ^ Johnson, Willard R. 1970. The Cameroon Federation; political integration in a fragmentary society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Perani, Judith (1998). The visual arts of Africa : gender, power, and life cycle rituals. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 215. ISBN 0-13-442328-3. OCLC 605230100.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pemberton III, John (2008). African Beaded Art: Power and Adornment. Northampton, Massachusetts: Smith College Museum of Art. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-87391-058-3.

- ^ Geary, Christraud (2008). Cameroon: Art and Kings. Museum Reitberg Zurich: Museum Reitberg Zurich. p. 183. ISBN 978-3-907077-35-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pemberton III, John (2008). African Beaded Art: Power and Adornment. Northampton, Massachusetts: Smith College Museum of Art. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-0-87391-058-3.

- ^ A.I.D. Evaluation Special Study No. 15 THE PRIVATE SECTOR: - Individual Initiative, And Economic Growth In An African Plural Society The Bamileke Of Cameroon http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnaal016.pdf

- ^ Horowitz, Donald L.; Donald, Horowitz L.; Horowitz, Professor Donald L. (1985). Ethnic Groups in Conflict. University of California Press. p. 155. ISBN 9780520053854.

- ^ , Wikipedia, 2020-06-07, retrieved 2020-06-08

- ^ "Paul Kammogne Fokam", Wikipédia (in French), 2020-05-04, retrieved 2020-06-08

- ^ , Wikipedia, 2020-05-15, retrieved 2020-06-08

- ^ , Wikipedia, 2019-10-23, retrieved 2020-06-08

- ^ , Wikipedia, 2020-04-13, retrieved 2020-06-08

- ^ "Joseph Kadji Defosso", Wikipédia (in French), 2020-04-15, retrieved 2020-06-08

- ^ "Mathias Djoumessi", Wikipédia (in French), 2020-05-11, retrieved 2020-06-08

- ^ "Wilglory Tanjong | Department of African American Studies". aas.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2016; first ed. 2010), Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké, Paris: l’Harmattan, 2010, 338p.

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2008), Parlons bamiléké. Langue et culture de Bafoussam, Paris: L'Harmattan, 255p.

- Fanso, V.G. (1989) Cameroon History for Secondary Schools and Colleges, Vol. 1: From Prehistoric Times to the Nineteenth Century. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd, 1989.

- Neba, Aaron, Ph.D. (1999) Modern Geography of the Republic of Cameroon, 3rd ed. Bamenda: Neba Publishers, 1999.

- Ngoh, Victor Julius (1996) History of Cameroon Since 1800. Limbé: Presbook, 1996.

Further reading[]

- Knöpfli, Hans (1997—2002) Crafts and Technologies: Some Traditional Craftsmen and Women of the Western Grassfields of Cameroon. 4 vols. Basel, Switzerland: Basel Mission.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bamileke. |

| Scholia has a topic profile for Bamileke people. |

- Aleco Yemba.net - Online Dictionaries and Learning Tools for the Yemba Language

- Works by Bamileke artists at the University of Michigan Museum of Art

- Bamileke art at the University of Iowa Stanley Museum of Art

- Works by Bamileke artists at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Works by Bamileke artists at the Brooklyn Museum

- Bamileke people

- Ethnic groups in Cameroon

- Semi-Bantu