Battle of Chaldiran

| Battle of Chaldiran | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman–Persian Wars | |||||||

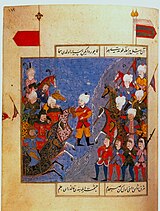

Artwork of the Battle of Chaldiran at the Chehel Sotoun Pavilion in Isfahan | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

60,000[9] or 100,000[10][11] 100–150 cannon[12] or 200 cannon and 100 mortars[8] |

40,000[13][11] or 55,000[14] or 80,000[10] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Heavy losses[15] or less than 2,000 [16] |

Heavy losses[15] or approximately 5,000 [17] | ||||||

| |||||||

The Battle of Chaldiran (Persian: جنگ چالدران; Turkish: Çaldıran Savaşı) took place on 23 August 1514 and ended with a decisive victory for the Ottoman Empire over the Safavid Empire. As a result, the Ottomans annexed Eastern Anatolia and northern Iraq from Safavid Iran.[3][18] It marked the first Ottoman expansion into Eastern Anatolia (Western Armenia), and the halt of the Safavid expansion to the west.[19] The Chaldiran battle was just the beginning of 41 years of destructive war, which only ended in 1555 with the Treaty of Amasya. Though Mesopotamia and Eastern Anatolia (Western Armenia) were eventually reconquered by the Safavids under the reign of Shah Abbas the Great (r. 1588–1629), they would be permanently lost to the Ottomans by the 1639 Treaty of Zuhab.

At Chaldiran, the Ottomans had a larger, better equipped army numbering 60,000 to 100,000 as well as many heavy artillery pieces, while the Safavid army numbered some 40,000 to 80,000 and did not have artillery at its disposal. Ismail I, the leader of the Safavids, was wounded and almost captured during the battle. His wives were captured by the Ottoman leader Selim I,[20] with at least one married off to one of Selim's statesmen.[21] Ismail retired to his palace and withdrew from government administration[22] after this defeat and never again participated in a military campaign.[19] After their victory, Ottoman forces marched deeper into Persia, briefly occupying the Safavid capital, Tabriz, and thoroughly looting the Persian imperial treasury.[6][7]

The battle is one of major historical importance because it not only negated the idea that the Murshid of the Shia-Qizilbash was infallible,[23] but also led Kurdish chiefs to assert their authority and switch their allegiance from the Safavids to the Ottomans.[24]

Background[]

After Selim I's successful struggle against his brothers for the throne of the Ottoman Empire, he was free to turn his attention to the internal unrest he believed was stirred up by the Shia Qizilbash, who had sided with other members of the Dynasty against him and had been semi-officially supported by Bayezid II. Selim now feared that they would incite the population against his rule in favor of Shah Isma'il leader of the Shia Safavids, believed by some of his supporters to be descended from the Prophet. Selim secured a jurist opinion that described Isma'il and the Qizilbash as "unbelievers and heretics" enabling him to undertake extreme measures on his way eastward to pacify the country.[25] Selim accused Ismail of departing from the faith:[26]

... you have subjected the upright community of Muhammad... to your devious will [and] undermined the firm foundation of the faith; you have unfurled the banner of oppression in the cause of aggression [and] no longer uphold the commandments and prohibitions of the Divine Law; you have incited your abominable Shii faction to unsanctified sexual union and the shedding of innocent blood.

Before Selim started his campaign, he ordered for the execution of some 40,000 Qizilbash of Anatolia, "as punishment for their rebellious behavior".[11] He then also tried to block the import of Iranian silk into his realm, a measure which met "with some success".[11]

The declaration of war by Selim I, was sent in the form of a letter:[27]

I, the glorious Sultan ... address myself to thee, Amir Ismail, chief of the Persian troops, who art like in tyranny to Zohak and Afrasiab, and art destined to perish like the last Dara."

When Selim started his march east, the Safavids were invaded in the east by the Uzbeks. The Uzbek state had been recently brought to prominence by Muhammad Shaybani, who had fallen in battle against Isma'il only a few years before. Attempting to avoid having to fight a war on two fronts, Isma'il employed a scorched earth policy against Selim in the west.[28]

Selim's army was discontented by the difficulty in supplying the army in light of Isma'il's scorched earth campaign, the extremely rough terrain of the Armenian Highland, and the fact that they were marching against Muslims. The Janissaries even fired their muskets at the Sultan's tent in protest at one point. When Selim learned of the Safavid army forming at Chaldiran he quickly moved to engage Isma'il, in part to stifle the discontent of his army.[29]

Battle[]

The Ottomans deployed heavy artillery and thousands of Janissaries equipped with gunpowder weapons behind a barrier of carts. The Safavids, who did not have artillery at their disposal at Chaldiran,[30] used cavalry to engage the Ottoman forces. The Safavids attacked the Ottoman wings in an effort to avoid the Ottoman artillery positioned at the center. However, the Ottoman artillery was highly maneuverable and the Safavids suffered disastrous losses.[31] The advanced Ottoman weaponry was the deciding factor of the battle as the Safavid forces, who only had traditional weaponry, were decimated. The Safavids also suffered from poor planning and ill-disciplined troops unlike the Ottomans.[32]

Aftermath[]

Following their victory the Ottomans captured the Safavid capital city of Tabriz on 7 September,[19] which they first pillaged and then evacuated. That week's Friday sermon in mosques throughout the city was delivered in Selim's name.[33] Selim was however unable to press on after Tabriz due to the discontent amongst the Janissaries.[19] The Ottoman Empire successfully annexed Eastern Anatolia (encompassing Western Armenia) and northern Mesopotamia from the Safavids. These areas changed hands several times over the following decades however; the Ottoman hold would not be set until the 1555 Peace of Amasya following the Ottoman-Safavid War (1532–1555). Effective governmental rule and eyalets would not be established over these regions until the 1639 Treaty of Zuhab.[citation needed]

After two of his wives and entire harem were captured by Selim[34][19] Ismail was heartbroken and resorted to drinking alcohol.[35] His aura of invincibility shattered,[36] Ismail ceased participating in government and military affairs,[37] due to what seems to have been the collapse of his confidence.[19]

Selim married one of Ismail's wives to an Ottoman judge. Ismail sent four envoys, gifts, and in contrast to their previous exchanges, words of praise to Selim in order to help retrieve her. Instead of giving his wife back, Selim cut the messengers' noses off and sent them back empty handed.[33]

After the defeat at Chaldiran, however, the Safavids made drastic domestic changes. From then on, firearms were made an integral part of the Persian armies and Ismail's son, Tahmasp I, deployed cannons in subsequent battles.[38][39]

During the retreat of the Ottoman troops, they were intensively harassed by Georgian light cavalry of the Safavid army, deep into the Ottoman realm.[40]

The Mamluk Sultanate refused to send messengers to congratulate Selim after the battle and prohibited celebrating the Ottoman military victory. In contrast, the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople led to days of festivities in the Mamluk capital, Cairo.[33]

After the victorious battle of Chaldiran, Selim I next threw his forces southward to fight the Mamluk Sultanate in the Ottoman–Mamluk War (1516–1517).[41]

Battlefield[]

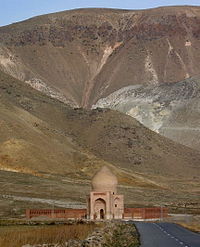

The site of the battle is near Chala Ashaqi village, around 6 km west of the town of Siyah Cheshmeh, south of Maku, north of Qareh Ziyaeddin. A large brick dome was built at the battlefield site in 2003 along with a statue of Seyid Sadraddin, one of the main Safavid commanders.[citation needed]

Quotes[]

After the battle, Selim believed Ismail I was:

Always drunk to the point of losing his mind and totally neglectful of the affairs of the state.[42]

Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat:[43]

At that period Sháh Ismail returned to Irák, where he was attacked by the Sultán of Rum, Sultán Salim, with an army of several hundred thousand men. Sháh Ismail met him with a force of 30,000, and a bloody battle was fought, from which he escaped with only six men, all the rest of his army having been annihilated by the Rumi. Sultán Salim made no further aggressions after this, but returned to Rum, while Sháh Ismail, broken and [with his forces] dispersed, remained in Irák. A short time after this event, he went to join his colleagues Nimrud and Pharaoh, and was succeeded by his son Sháh Tahmásp. This Sháh, likewise, was on several occasions exposed to the kicks of the Rumi army; moreover, from fear of the Rumi he was not able to maintain his accursed religion, nor uphold the evil practices of his father.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Mustafa Çetin Varlık (1988–2016). "ÇALDIRAN SAVAŞI Yavuz Sultan Selim ile Safevî Hükümdarı Şah İsmâil arasında Çaldıran ovasında 23 Ağustos 1514'te yapılan meydan savaşı". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 483. ISBN 978-1851096725.

- ^ Jump up to: a b David Eggenberger, An Encyclopedia of Battles, (Dover Publications, 1985), 85.

- ^ Morgan, David O. The New Cambridge History of Islam Volume 3. The Eastern Islamic World, Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge U, 2010. p.210 "Although the Safavids experienced military defeat at Chāldirān, the political outcome of the battle was a stalemate between the Ottomans and Safavids, even though the Ottomans ultimately won some territory from the Safavids. The stalemate was largely due to the ‘scorched earth’ strategy that the Safavids employed, making it impossible for the Ottomans to remain in the region"

- ^ Ira M. Lapidus. "A History of Islamic Societies" Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1139991507 p 336

- ^ Jump up to: a b Matthee, Rudi (2008). "SAFAVID DYNASTY". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

Following Čālderān, the Ottomans briefly occupied Tabriz.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Savory 2007, p. 42.

- ^ Keegan & Wheatcroft, Who's Who in Military History, Routledge, 1996. p. 268 "In 1515 Selim marched east with some 60,000 men; a proportion of these were skilled Janissaries, certainly the best infantry in Asia, and the sipahis, equally well-trained and disciplined cavalry. [...] The Persian army, under Shah Ismail, was almost entirely composed of Turcoman tribal levies, a courageous but ill-disciplined cavalry army. Slightly inferior in numbers to the Turks, their charges broke against the Janissaries, who had taken up fixed positions behind rudimentary field works."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, ed. Gábor Ágoston,Bruce Alan Masters, page 286, 2009

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d McCaffrey 1990, pp. 656–658.

- ^ Ágoston, Gábor (2014). "Firearms and Military Adaptation: The Ottomans and the European Military Revolution, 1450–1800". Journal of World History. 25: 110. doi:10.1353/jwh.2014.0005. S2CID 143042353.

- ^ Roger M. Savory, Iran under the Safavids, Cambridge, 1980, p. 41

- ^ Keegan & Wheatcroft, Who's Who in Military History, Routledge, 1996. p. 268

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kenneth Chase, Firearms: A Global History to 1700, 120.

- ^ Serefname II

- ^ Serefname II s. 158

- ^ Ira M. Lapidus. "A History of Islamic Societies" Cambridge University Press ISBN 1139991507 p 336

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Mikaberidze 2015, p. 242.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Iran, ed. William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, 224

- ^ Leslie P. Peirce, The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire, (Oxford University Press, 1993), 37.

- ^ Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shiʻi Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shiʻism, (Yale University Press, 1985), 107.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Iran, ed. William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, 359.

- ^ Martin Sicker, The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab conquests to the Siege of Vienna, (Praeger Publishers, 2000), 197.

- ^ Caroline Finkel, Osman's Dream, (Basic Books, 2006), 104. .

- ^ Caroline Finkel, Osman's Dream, 105.

- ^ "The Encyclopaedia Britannica; A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature Volume 18.". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 18. 1894. p. 635.

- ^ Caroline Finkel, Osman's Dream, 105

- ^ Caroline Finkel, Osman's Dream, 106.

- ^ Floor 2001, p. 189.

- ^ Andrew James McGregor, A Military History of Modern Egypt: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Ramadan War, (Greenwood Publishing, 2006), 17.

- ^ Gene Ralph Garthwaite, The Persians, (Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 164.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mikhail, Alan (2020). God's Shadow: Sultan Selim, His Ottoman Empire, and the Making of the Modern World. Liveright. ISBN 978-1631492396.

- ^ The Cambridge history of Iran, ed. William Bayne Fisher, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, pg. 224.

- ^ The Cambridge history of Islam, Part 1, ed. Peter Malcolm Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis, pg. 401

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam, Part 1, By Peter Malcolm Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis, p. 401.

- ^ Elton L. Daniel, The History of Iran (ABC-CLIO, 2012) 86

- ^ Gunpowder and Firearms in the Mamluk Sultanate Reconsidered, Robert Irwin, The Mamluks in Egyptian and Syrian politics and society, ed. Michael Winter and Amalia Levanoni, (Brill, 2004) 127

- ^ Matthee, Rudolph (Rudi). "Safavid Persia:The History and Politics of an Islamic Empire". Retrieved 26 May 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Floor 2001, p. 131.

- ^ Faroqhi, Suraiya (20 January 2018). The Ottoman Empire: A Short History. Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 9781558764491 – via Google Books.

- ^ Rudi Matthee, The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian history, 1500–1900, (Princeton University Press, 2005), 77

- ^ N. Elias (ed.). The Tarikh-i-Rashidi. Translated by E. Denison Ross. p. 247.

Sources[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Chaldiran. |

- Yves Bomati and Houchang Nahavandi,Shah Abbas, Emperor of Persia,1587–1629, 2017, ed. Ketab Corporation, Los Angeles, ISBN 978-1595845672, English translation by Azizeh Azodi.

- Floor, Willem (2001). Safavid Government Institutions. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-1568591353.

- McCaffrey, Michael J. (1990). "ČĀLDERĀN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 6. pp. 656–658.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- Savory, Roger (2007). Iran Under the Safavids. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521042512.

Further reading[]

- Floor, Willem (2020). "The Earliest Account of the Battle of Chaldiran?". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 170 (2): 371–395. doi:10.13173/zeitdeutmorggese.170.2.0371.

- Moreen, Vera B. (2019). "Echoes of the Battle of Čālderān: The Account of the Jewish Chronicler Elijah Capsali (c. 1490 - c. 1555)". Studia Iranica. 48 (2): 195–234. doi:10.2143/SI.48.2.3288439.

- Palazzo, Chiara (2016). "The Venetian News Network in the Early Sixteenth Century: The Battle of Chaldiran". In Raymond, Joad; Moxham, Noah (eds.). News Networks in Early Modern Europe. Brill. pp. 849–869. doi:10.1163/9789004277199_038. ISBN 9789004277175.

- Rahimlu, Yusof; Esots, Janis. "Chāldirān (Çaldıran)". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica Online. Brill Online. ISSN 1875-9831.

- Walsh, J.R. (1965). "Čāldirān". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 495469475.

- Wood, Barry (2017). "The Battle of Chālderān: Official History and Popular Memory". Iranian Studies. 50 (1): 79–105. doi:10.1080/00210862.2016.1159504. S2CID 163512376.

- Ottoman–Persian Wars

- 1514 in Asia

- 1514 in the Ottoman Empire

- 16th century in Iran

- Battles involving the Ottoman Empire

- Battles involving Safavid Iran

- Conflicts in 1514

- History of West Azerbaijan Province

- History of Tabriz

- History of East Azerbaijan Province

- Shia–Sunni sectarian violence

- Western Armenia

- Early Modern history of Iraq