Battle of Ctesiphon (363)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

| Battle of Ctesiphon (363) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Julian's Persian War | |||||||

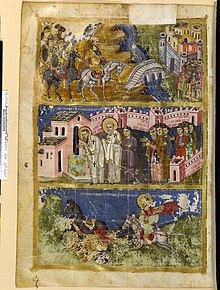

Julian near Ctesiphon; medieval miniature | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Eastern Roman Empire Arsacid Armenia | Sassanid Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Julian |

Merena Surena Pigranes Narseus | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 83,000 men[1]-60,000[2] | Presumably larger than Roman force[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 70[2] | 2500[2] | ||||||

The Battle of Ctesiphon took place on May 29, 363 between the armies of Roman Emperor Julian and an army of the Sasanian Empire (during Shapur II's reign) outside the walls of the Persian capital Ctesiphon. The battle was a Roman victory,[3] but eventually the Roman forces found themselves unable to continue their campaign as they were too far from their supply lines.

Background[]

On November 3, 361, Constantius II died in the city of Mobsucrenae, leaving his cousin Flavius Claudius Julianus, known to history as Julian the Apostate, as sole Emperor of Rome. Arriving at Constantinople to oversee Constantius' burial, Julian immediately focused on domestic policy and began to greatly reform the Roman Imperial government by reorganizing, streamlining, and reducing the bureaucracy.

Turning next to foreign policy, Julian saw the previously unchecked military incursions of Shapur II of Persia against the Eastern Roman provinces as posing the greatest external threat. After many failed earlier attempts, the Persian king launched a more successful second campaign against the Romans and captured Amida in 359, controlling the headwaters of the Tigris and the entrance to Asia Minor from the east. A Roman offensive was desperately needed to halt Shapur.

With Julian's reputation and exploits during his years as Caesar and general of Gaul preceding him, Shapur preferred to negotiate a peace treaty with the intrepid young Julian. Believing it to be incumbent on himself to produce a more permanent settlement in the East, Julian responded to Shapur's calls for peace by saying that the Persian king would be seeing him very soon and began preparing for an expedition against the Sassanid dynasty, collecting all his legions and marching east from Constantinople. Carefully planning and crafting his Persian campaign for over a year, Julian transferred his capital and forward base for the coming war to Antioch, Syria in the summer of 362 and on March 5, 363, set out with 65,000–83,000,[4][5] or 80,000–90,000 men,[6] while Shapur, along with the main Persian army, spah, was away from Ctesiphon. Per his devised plan of attack, Julian sent 18,000 soldiers under the command of his maternal cousin Procopius to Armenia, with the aim of obtaining support from the King of Armenia for a clever and not looked-for double pincer movement against Shapur.

The battle[]

Seeing Julian successfully march into his dominions, Shapur ordered his governors to undertake a scorched earth policy until he reached the Sassanid capital, Ctesiphon, with the main Persian army. However, after a few minor skirmishes and sieges Julian arrived with his undefeated army[7] before Shapur II to the walls of Ctesiphon on May 29.

Outside the walls a Persian army under Merena was formed up for battle across the Tigris. According to Ammianus Marcellinus, the Persian army featured cataphracts (clibanarii), backed up by infantry in very close order. Behind them there were war elephants.[8]

Julian's force attempted to set foot on the opposite shore of Tigris, under harassment by the Persians.[9] After achieving it, the main battle commenced. It was a stunning tactical victory for the Romans, losing only 70 men to the Persians' 2,500 men.[2] One of the Christian sources and not one friendly to the pagan Julian, Socrates Scholasticus, even states that Julian's victories up to this point in the campaign had been so great that they caused Shapur to offer Julian a large portion of the Persian domains if he and his legions would withdraw from Ctesiphon. But Julian rejected this offer out of desire for the glory of taking the Persian capital and defeating Shapur in battle which would earn him the honorific of Parthicus. However, Julian lacked the equipment to lay siege to the strongly fortified Ctesiphon, and the main Sassanid army, commanded by Shapur and far larger than the one just defeated, was closing in quickly. Also critical was the failure of Procopius to arrive with the 18,000 detachment of the Roman army that could have aided Julian in crushing Shapur's approaching force as he had intended. For as previously captured satraps had testified after being fairly treated by Julian, the capture or death of Shapur would have compelled the Persian city to open its gates to the new Roman conqueror. While Julian was in favor of advancing further into Persian territory, he was overruled by his officers. Roman morale was low, disease was spreading, and there was very little forage around.[citation needed]

Aftermath[]

This section does not cite any sources. (July 2021) |

Reluctantly, Julian agreed to retreat back along the Tigris and look for Procopius and the other half of his army that had failed to coordinate the double-pincers movement with him outside of Ctesiphon as had been planned. On June 16, 363, the retreat began. Ten days later, after an indecisive Roman victory at Maranga, the army’s rearguard came under heavy attack, in the Battle of Samarra. Not even pausing to put on his armour, Julian plunged into the fray shouting encouragement to his men. Just as the Persians were beginning to pull out with heavy losses, Julian was struck in the side by a flying spear. He died before midnight, on June 26, 363. Ultimately the campaign failed and the Romans were forced to ask for peace under unfavourable terms.

Citations[]

- ^ Shahbazi 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Tucker 2010, p. 160.

- ^ Browning 1978, p. 243.

- ^ Zosimus, Historia Nova, book 3, chapter 12. Zosimus' text is ambiguous and refers to a smaller force of 18,000 under Procopius and a larger force of 65,000 under Julian himself; it's unclear if the second figure includes the first.

- ^ Elton, Hugh, Warfare in Roman Europe AD 350–425, p. 210, using the higher estimate of 83,000.

- ^ Bowersock, Julian the Apostate, p.108.

- ^ Lieu & Montserrat 1996, p. 208.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, Book 24, 6.3 το 6.8.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, Book 24, 6.10 to 6.12.

References[]

- Bowersock, Glen Warren. Julian the Apostate. London, 1978. ISBN 0-674-48881-4

- Browning, Robert (1978). The Emperor Julian. University of California Press.

- Lieu, Samuel N.C.; Montserrat, Dominic (1996). From Constantine to Julian: Pagan and Byzantine views: A Source History. Routledge.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005-07-20). "Sasanian dynasty". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict. 1. ABC-CLIO.

- Wacher, J.S. (2001). The Roman World. 1 (2 ed.). Routledge.

- 4th-century conflicts

- Battles of the Roman–Sasanian Wars

- 360s in the Byzantine Empire

- 4th century in Iran

- Ancient history of Iraq

- Julian (emperor)

- Sieges of Ctesiphon

- 363

- Julian's Persian expedition