Battle of Nedumkotta

| Battle of Nedumkotta | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Anglo-Mysore War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total: 35000[3] |

Total: 50000[8] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1000 killed and wounded[11] | 200 killed and wounded[12] | ||||||

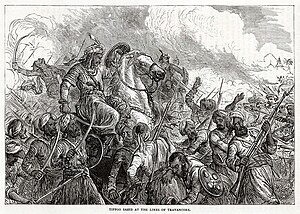

The Battle of Nedumkotta took place between December 1789 and May 1790, and was a reason for the opening of hostilities in the Third Anglo-Mysore War. This battle was fought between Tipu Sultan of the Kingdom of Mysore and Dharma Raja, Maharaja of Travancore. Mysore army attacked the fortified line at the Travancore border known as the Nedumkotta in Thrissur district. The Mysore army was successfully repulsed by Travancore army under the leadership of Raja Kesavadas, Dewan of Travancore.

Situation in Travancore[]

The strength of the Travancore Army was greatly reduced after several earlier battles with Hyder Ali's forces.[citation needed]. The death of the Dutch-born commander Valiya-kappitan Eustachius De Lannoy in 1777 further diminished the morale of the soldiers. The death of Makayiram Thirunal and Asvati Thirunal in 1786 forced the Travancore royal family to adopt two princesses from Kolathunad. As the threat of an invasion by Tipu Sultan loomed in the horizon, Travancore's maharajah Dharma Raja tried to rebuild his army by appointing Chempakaraman Pillai as the Dalawa and Kesava Pillai as the .[13]: 385

Preparations for the battle[]

Tipu Sultan planned the invasion of Travancore for many years, and he was especially concerned with the Nedumkotta fortifications, which had prevented his father Hyder Ali from annexing the kingdom. Towards the end of 1789, Tipu Sultan marched his troops from Coimbatore. Tipu's army consisted of 20,000 infantry, 10,000 spearmen and match-lockmen, 5,000 cavalry and 20 field guns.[13]: 390

Travancore Army numbered above 50,000 trained troops of all branches, such as infantry, cavalry, artillery and irregular troops, trained and drilled according to European discipline. They were mostly armed with European weapons, procured through the English and the Dutch. This force was commanded by Europeans, Eurasians, Nairs and Pashtuns.[14]

Travancore purchased the strategic forts of Cranganore and Ayacottah from the Dutch to improve the country's defenses. The deal was finalized by Dewan Kesava Pillai and Dutch merchants David Rabbi and Ephraim Cohen under the observation of Maharajah Dharma Raja and Dutch East India Company Governor John Gerard van Anglebeck.[14]Both Tipu Sultan and Governor John Holland of Madras objected to these purchases because the forts, though they had long been in Dutch possession, were in the Kingdom of Cochin[13]: 391

Kesava Pillai was appointed as the Commander-in-Chief of the Travancore Army. To boost the strength of the armed forces, several thousand young militiamen were called up from all over the kingdom. The forts of Cranganore and Ayacottah were repaired and garrisoned.[13]: 393 Tipu sent a letter to the King of Travancore demanding the withdrawal of the Travancori forces garrisoned in Cranganore Fort, the transfer to him of Malabar chiefs and nobles that had been sheltered by the king, and the demolition of Travancore ramparts built within the territory of Cochin. The king refused the sultan's demands.[13]: 393

The first clash[]

A number of Mysorean soldiers encroached into Travancorean jungles, ostensibly to apprehend fugitives, and came under fire when discovered by patrols of the Paravoor Battalion of the Travancore Army.[9][13][14] On 28 December 1789, Mysorean troops attacked the eastern part of the Travancori lines and captured the ramparts as the Travancoreans retreated, but were eventually stopped when the Travancorean force of 800 Nairs made a stand with the help of a 6-pounder gun;[9][14]At first, the Mysoreans overpowered three batteries of the Lines. But subsequently they were subjected to fire from the woods. They were surprised by the first round of fire and fell in disorder. In this confusion, the party of twenty men of the Travancore garrison, threw in a regular platoon on the flank which killed the commanding officer of Mysore Army, and threw the corps into inextricable disorder and flight.[14]

Travancori reinforcements arrived during the four-hour battle, the panic now became general and the retreating Mysorean soldiers were borne on to the ditch, while others were forced into it by the mass which pressed on from behind. Those Mysoreans who had not yet been trampled by their horses while retreating to the point from where they had invaded the lines found that the sacks with cotton, used for filling up the ditch, when they set up as well as some powder barrels, had caught fire. This forced them to jump from the ramparts.[15] Those that fell into the ditch were killed. The rear now became the front. The bodies that filled the ditch enabled the remainder to pass over them. The Sultan himself was thrown down in the struggle and the bearers of his palanquin trampled to death. Though he was rescued from death by some of his faithful followers, yet he received injuries.[14] Mysoreans lost around 1000 soldiers and fled in panic.[9]: 163 [16] Travancorean casualties numbered around 200.[13] Several Mysorean troops were captured as prisoners of war, including soldiers of European and Maratha origin.[13]: 395 Travancore Army recovered the sword, the palanquin, the dagger, the ring and many other personal effects of Tipu Sultan from the ditches of the Nedumkotta and presented them to the ruler of Travancore. Some of them were sent to the Nawab of Carnatic on his request.[14]

The second battle[]

Tipu Sultan now determined on retaliating on Travancore. He remained in the vicinity of the northern frontier and concentrated a large army there which consisted of infantry, cavalry and artillery.The Madras Government was duly informed of the above proceedings of the Sultan, and the Maha Rajah received assurances of assistance from the British Governor, in the event of Tipu' s invasion of his country. In the meantime, Travancore repaired their northern frontier line and all available troops were concentrated there. Recruits were enlisted, and guns, stores and ammunition were stored in the arsenals.[14]

On 1 March 1790, 1,000 Travancore troops advanced onto Mysore territory, where they were stopped and pushed back with considerable losses by Mysorean troops.[9]: 166 Tipu's artillery began to work on 6 March. Finding no perceptible effect on the wall, a few more batteries were erected close to the northern wall and the largest guns were mounted, which opened a destructive fire[14].On 9 April 1790, a similar attempt was made once again by 1,500 Travancore troops on Mysore territory, however, they were once again stopped by Mysorean troops and repulsed.[9]: 166 The wall resisted the Mysorean fire for nearly a month and on 15 April, a practicable breach of three-quarter of a mile in length was effected. The Travancore troops abandoned the Travancore lines and retreated. Tipu Sultan took approximately 6,000 soldiers and advanced on the Travancore position.[9]: 167 On 18 April 1790, Tipu arrived within one mile of Cranganur and erected batteries.[9]: 167 On 8 May 1790, Tipu successfully occupied Cranganur.[9]: 167 Soon Travancorean forces abandoned the forts such as Ayicotta and Parur and retreated.[9]: 167

A portion of Mysorean troops under de Lalée proceeded to Kuriapilly, which fort was also abandoned by the Travancoreans. The whole line thus fell into the hands of the Sultan, together with 200 pieces of cannon of various sizes and metal and an immense quantity of. ammunition and other warlike stores, which were forwarded to Coimbatore as trophies.[14]While the warfare was going on, the two English regiments stationed at Aycottah and another brigade consisting of a European and two native regiments just landed from Bombay under Colonel Hartlay at Monambam and Palliport, remained passive spectators of all these on the plea that no orders had been received by them, from the Governor of Madras, to fight against the Sultan. The Sultan's first object was to destroy the Travancore lines and fill up the ditch, and so he took a pickaxe himself and set an example which was followed by every one present and the demolition of the wall was completed by his army without much delay.[14]

Tipu Sultan advanced as far as Alwaye.[14]The south-west monsoon broke out with unusual severity and Aluva river, a stream which usually rises after a few showers, filled and overflowed its banks causing Tipu's army great inconvenience and rendering their march almost impossible. The current, during the freshes in the river was so strong, that even the permanent residents of the adjacent villages find difficulty in crossing it at that time. As the country around is mostly intersected by numerous rivers and streams, and intermixed with large paddy fields submerged under water at this season, Tipu and his army were surprised at a scene which they had seldom witnessed before, and were bewildered by their critical situation. His army had no shelter ; no dry place for parade ; all their ammunition and accoutrements got wet and the provisions became scanty.[14]

Kesava Pillai, after leaving Paravoor, strengthened the garrison at every military station, both at the sea beach and at Arookutty and other places, erected stockades, at every backwater passage, fortified the line and batteries between Kumarakam and the Kundoor hills at Poonjar. All the responsible officers, both military and revenue, were posted at different places and the divisional revenue authorities were directed to remain at intermediate stations and raise irregular militia, armed with whatever descriptions of weapon the people could get at the moment, such as bows, arrows, swords and cudgels. He informed the Maha Raja that Tipu Sultan's progress from Aluva was totally impeded on account of the rain, and any attempt to march with his army from Aluva to up-country, would be impeded by the natural defences of the country and that the line between Kumarakam and Kundoor hills had been strongly barricaded while a regular militia lined the hills and the sea.[14]

The British Governor of Madras addressed Dharma Raja, assuring that preparations were in progress for attacking Tipu Sultan. While Tipu was in his uncomfortable encampment at Aluva, intelligence of the commencement of hostilities and the assembling of a large English force at Trichinopoly reached him. The Sultan was under the necessity of beating a precipitate retreat. The rivers were all full. The country was under water. Except boats, no other means of communication could be used in that part of the country at that time. Tipu Sultan divided his army into two portions and ordered one portion to retreat via Chalakudy to Trichoor and thence to Palghat, and the other via Cranganore and Chavakkad to Palghat.[14]

Aftermath[]

Mysore's actions against Travancore breached the Treaty of Mangalore, which led to further conflict with the British Empire, and led to the Third Anglo-Mysore War. The Travancore force joined the British army at Falghautcherry, Coimbatore and Dindigul, and fought under the command of British officers against Mysore up to the conclusion of the war and the Treaty of Seringapatam.[14]The Mysorean invasion provided the East India Company more chances to conquer and tighten their grip on the ancient feudal principalities of Malabar and to compell the Travancore to accept the subsidiary alliance of the company.[14]

See also[]

- Battle of Colachel

- Mysore's campaigns against the states of Malabar (1757)

- Mysorean invasion of Malabar

- Battle of Tirurangadi

- Capture of Cannanore

References[]

- ^ Mia Carter, Barbara Harlow (31 December 2003), Archives of Empire: Volume I. From The East India Company to the Suez Canal, p. 174, ISBN 0822331640CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (11 July 1906), Travancore State Manual, Trivandrum, p. 395

- ^ Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (11 July 1906), Travancore State Manual, Trivandrum

- ^ Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (11 July 1906), Travancore State Manual, Trivandrum, p. 395

- ^ Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (11 July 1906), Travancore State Manual, Trivandrum, p. 395

- ^ Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (11 July 1906), Travancore State Manual, Trivandrum, p. 395

- ^ Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (11 July 1906), Travancore State Manual, Trivandrum, p. 395

- ^ Menon, P.Shungoony (1 January 1878), A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times, Higginbotham

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Mohibbul Hasan (2005). History of Tipu Sultan. Aakar Books. ISBN 9788187879572.

- ^ Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (11 July 1906), Travancore State Manual, Trivandrum

- ^ Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (11 July 1906), Travancore State Manual, Trivandrum, p. 395

- ^ Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (11 July 1906), Travancore State Manual, Trivandrum, p. 395

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (1906). "History". Modern History–Rama Varma. Travancore State Manual. 1. .

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Menon, P. Shungoony (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. Madras: Higgin Bothyam and co.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Van Lohuizen, Jan (1961). "The Dutch and Tipu Sultan, 1784—1790". The Dutch East India Company and Mysore 1762-1790. 31. Brill. pp. 135–163. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctvbqs37w.10.

- ^ John Clark Marshman (1863), The history of India, p. 450

Sources[]

- Fortescue, John William (1902). A history of the British army, Volume 3. Macmillan.

- Marshman, John Clark (1863). The history of India

- Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (1906). The Travancore State Manual, Volume 1, p. 390. (detail on the battles)

- A history of Travancore from the earliest times, Volume 1 (details on fort transactions preceding attack)

- 1789 in India

- History of Kerala

- History of Thrissur district

- Conflicts in 1789

- Battles involving the Kingdom of Mysore

- Battles involving Travancore

- Battles involving Great Britain

- Battles of the Third Anglo-Mysore War

- Military history of India

- Mysorean invasion of Malabar

- Kingdom of Cochin