Baylisascaris shroederi

| Baylisascaris shroederi | |

|---|---|

| |

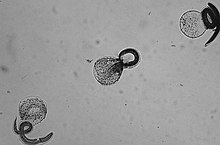

| Freshly hatched B. shroederi larvae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | B. shroederi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Baylisascaris shroederi | |

| Baylisascaris shroederi | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Giant panda roundworm |

| Specialty | Veterinary medicine |

Baylisascaris shroederi, common name giant panda roundworm, is a roundworm (nematode), found ubiquitously in giant pandas of central China, the definitive hosts. Baylisascaris larvae in paratenic hosts can migrate, causing visceral larva migrans (VLM). It is extremely dangerous to the host due to the ability of the parasite's larvae to migrate into brain tissue and cause damage. Concern for human infection is minimal as there are very few giant pandas living today and most people do not encounter giant pandas in their everyday activities. There is growing recognition that the infection of Baylisascaris shroederi is one of the major causes of death in the species. This is confirmed by a report stating that during the period of 2001 to 2005; about 50% of deaths in wild giant pandas were caused by the parasite infection.[1][2]

Cause[]

Transmission[]

In central China, B. shroederi infection rates in giant pandas are very high, being found in around 95% of adult giant pandas and 90% of juvenile pandas.[3] Transmission occurs similarly to other roundworm species, through the fecal-oral route. Eggs are produced by the worm while in the intestine, and the released eggs will mature to an infective state externally in the soil. When an infected egg is ingested, the larvae will hatch and enter the intestine. Transmission of B. schroderi may also occur through the ingestion of larvae found in infected tissue.[4]

Life cycle[]

An adult worm lives and reproduces in the intestine of its definitive host, the giant panda. The female worm can produce over 100,000 eggs per day. Eggs are excreted along with feces, and become infective in the soil after 2–4 weeks. If ingested by another giant panda, the life cycle repeats. However, if these eggs are ingested by a possible paratenic host (small mammals, birds) the larvae will penetrate the intestinal lumen of the host and migrate into tissues. Larvae tend to migrate to the brain and other vital organs, cause damage, and affect the behavior of the intermediate host, making it an easier prey for pandas if they needed to eat meat. Reproduction does not occur in these paratenic hosts; however, if a panda were to prey on an infected paratenic host, the encysted larvae could become adults in the panda and the cycle could resume.[5] Because the giant panda is almost entirely vegetarian, chance of infection due to ingestion of a paratenic, or reservoir host is very low and uncommon. Pandas will rarely consume small rodents and branch out from their typical bamboo diet. It is estimated that 99 percent of a panda's diet consists of the stems, leaves and chutes from various bamboo species.[6]

Infection in humans[]

The potential for human infection has not been studied and there have been no confirmed cases of this species of Baylisascaris infecting a human host. Similar species such as Baylisascaris procyonis have been found to infect humans in rare cases. So, the potential for human infection may be possible, just has not been studied because no cases have arisen with this species of roundworm.

Diagnosis[]

Diagnosis of B. shroederi infestation is through identification of larvae in tissue examination. Diagnosis requires forehand knowledge along with understanding and recognition of larval morphologic characteristics. Distinguishing features of B. shroederi larvae in tissue are its relatively large size and prominent single lateral alae. Sometimes serologic testing is used as supportive evidence, although no commercial serologic test is currently available.[7][8]

Other diagnosis methods include: brain biopsy, neuroimaging, electroencephalography, differential diagnoses among other laboratory tests.[9]

As small numbers of larvae can cause severe disease, and larvae occur randomly in tissue, a biopsy usually fails to include larvae and therefore leads to negative results. The identification of the morphologic characteristics takes practice and experience and may not be accurately recognized or could be misidentified. The fact that no commercial serologic test exists for the diagnosis of B. shroederi infection makes the diagnosis and treatment more difficult.[10]

Prevention[]

Educating the public about the unknown dangers of contact with pandas or their feces is the most important preventive step.[11] Parents should encourage their children to practice good hygiene; hand-washing after outdoor play or contact with animals is very important. Close contact with giant pandas is highly discouraged without wearing proper personal protective equipment such as gloves and long sleeves. Boiling water, steam-cleaning, flaming, or fire are highly effective and are easily accessible means to decontaminate objects or areas contaminated with eggs and feces. Materials contaminated by B. shroederi should be incinerated. Contaminated areas can be cleaned with a xylene-ethanol mixture. Common chemical disinfectants are not effective against B. shroederi eggs. Disinfectants like 20% bleach (1% sodium hypochlorite) washes away the eggs but does not kill them. Since treatment is not very effective, the best way to escape this parasite is to practice the prevention methods.[12]

Epidemiology[]

B. shroederi is found abundantly in its definitive host, the giant panda. Similar roundworms from Baylisascaris genus have been found to infect up to 90 other wild and domestic animal species. Very little research has been done on the potential of human infection with this roundworm, but the possibility is still taken with precautions when handling the pandas and fecal samples.[13] Many of these animals act as paratenic hosts and the infection results in the penetration of the gut wall by the larvae and subsequent invasion of tissue, resulting in severe disease. In animals, it is the most common cause of larva migrans.[14] The paratenic host, however, cannot shed infective eggs, as the larva will not complete its life cycle until it makes its way into a panda. In pandas, there are no confirmed paratenic hosts for this roundworm and it has never been found in humans.

References[]

- ^ Zhang JS, Daszak P, Huang HL, Yang GY, Kilpatrick AM, et al. (2008) Parasite threat to panda conservation. EcoHealth 5: 6–9.

- ^ Zhang L, Yang X, Wu H, Gu X, Hu Y, et al. (2011) The parasites of giant pandas: individual-based measurement in wild animals. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 47(1): 164–171.\

- ^ Sorvillo, F.; Ash, L. R.; Berlin, O. G.; Morse, S. A. (2002). "Baylisascaris procyonis: An Emerging Helminthic Zoonosis". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 355–359. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010273. PMC 2730233. PMID 11971766.

- ^ Sorvillo, F.; Ash, L. R.; Berlin, O. G.; Morse, S. A. (2002). "Baylisascaris procyonis: An Emerging Helminthic Zoonosis". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 355–359. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010273. PMC 2730233. PMID 11971766.

- ^ Drisdelle R. Parasites. Tales of Humanity's Most Unwelcome Guests. Univ. of California Publishers, 2010. p. 189f. ISBN 978-0-520-25938-6.

- ^ World Wildlife Fund. “What do pandas eat?” Eating habits of the giant panda. WWF, n.d. Web. 26 Apr. 2017. <http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/endangered_species/giant_panda/panda/what_do_pandas_they_eat/>

- ^ Gavin, P. J.; Kazacos, K. R.; Shulman, S. T. (2005). "Baylisascariasis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (4): 703–18. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.4.703-718.2005. PMC 1265913. PMID 16223954.

- ^ Sorvillo, F.; Ash, L. R.; Berlin, O. G.; Morse, S. A. (2002). "Baylisascaris procyonis: An Emerging Helminthic Zoonosis". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 355–359. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010273. PMC 2730233. PMID 11971766.

- ^ Gavin, P. J.; Kazacos, K. R.; Shulman, S. T. (2005). "Baylisascariasis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (4): 703–18. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.4.703-718.2005. PMC 1265913. PMID 16223954.

- ^ Sorvillo, F.; Ash, L. R.; Berlin, O. G.; Morse, S. A. (2002). "Baylisascaris procyonis: An Emerging Helminthic Zoonosis". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 355–359. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010273. PMC 2730233. PMID 11971766.

- ^ Gavin, P. J.; Kazacos, K. R.; Shulman, S. T. (2005). "Baylisascariasis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (4): 703–18. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.4.703-718.2005. PMC 1265913. PMID 16223954.

- ^ 4. Gavin, P. J.; Kazacos, K. R.; Shulman, S. T. (2005). "Baylisascariasis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (4): 703–18. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.4.703-718.2005. PMC 1265913. PMID 16223954.

- ^ Sorvillo, F.; Ash, L. R.; Berlin, O. G.; Morse, S. A. (2002). "Baylisascaris procyonis: An Emerging Helminthic Zoonosis". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (4): 355–359. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010273. PMC 2730233. PMID 11971766.

- ^ Gavin, P. J.; Kazacos, K. R.; Shulman, S. T. (2005). "Baylisascariasis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (4): 703–18. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.4.703-718.2005. PMC 1265913. PMID 16223954.

External links[]

- Parasitic nematodes of mammals

- Ascaridida