Bengal cat

| Bengal Cat | |

|---|---|

A female Bengal Cat with tricolored rosettes and a clear coat. | |

| Origin | Bangladesh and India |

| Foundation bloodstock | Egyptian Mau, Abyssinian, and others (domestic); Asian leopard cat (wild) |

| Breed standards | |

| CFA | standard |

| FIFe | standard |

| TICA | standard |

| WCF | standard |

| ACF | standard |

| ACFA/CAA | standard |

| CCA-AFC | standard |

| GCCF | standard |

| standard | |

| Feline hybrid (Felis catus × Prionailurus bengalensis bengalensis) | |

The Bengal cat is a domesticated cat breed created from hybrids of domestic cats, especially the spotted Egyptian Mau, with the Asian leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis). The breed name comes from the leopard cat's taxonomic name.

Bengals have a wild appearance; their golden shimmer comes from their leopard cat ancestry, and their coats may show spots, rosettes, arrowhead markings, or marbling. They are an energetic breed which needs much exercise and play.

History[]

Early history[]

The earliest mention of an Asian leopard cat × domestic cross was in 1889, when Harrison Weir wrote of them in Our Cats and All About Them.[1]

Early breeding efforts always stopped after just one or two generations. Jean Mill was the breeder who decided to make a domestic cat with a coat like a wild cat.

Bengals as a breed[]

Jean Mill of California is given credit for the modern Bengal breed. She had a degree in psychology from Pomona College and had taken several graduate classes in genetics at University of California, Davis.[2]

She made the first known deliberate cross of an Asian leopard cat with a domestic cat (a black California tomcat).[3] However, Bengals as a breed did not really begin in earnest until much later.[2] In 1970, Mill resumed her breeding efforts and in 1975 she received a group of Bengal cats which had been bred for use in genetic testing at Loma Linda University by Willard Centerwall.[4] Others also began breeding Bengals.[who?]

Cat registries[]

In 1983, the breed was officially accepted by The International Cat Association (TICA).[4] Bengals gained championship status in 1991.[5]

In 1997 The Governing Council of the Cat Fancy (GCCF) accepted Bengal cats.[6]

In 1999 Fédération Internationale Féline (FIFe) accepted Bengal cats into their registry.[7]

The Cat Fanciers' Association (CFA) was one of the last organizations to accept the Bengal cat into their registry. "The CFA board accepted the Bengal as Miscellaneous at the February 7, 2016 board meeting. In order for a Bengal cat to be registered with the CFA it must be F6 or later (6 generations removed from the Asian Leopard Cat or non-Bengal domestic cat ancestors)."[8]

In 1999 The Australian Cat Federation (ACF) accepted the Bengal cat into their registry.[9]

Early generation Bengal cat[]

Bengal cats from the first three filial generations of breeding (F1–G3) are considered "foundation cats" or "Early Generation" Bengals. The Early generation (F1–G3) males are frequently infertile. Therefore, female early generation Bengals of the F1, G2, and G3 are bred to fertile domestic Bengals.[3] F1 hybrid Bengal females are fertile, thus they are used in subsequent, unidirectional back-cross matings to fertile domestic cat males. Some male Bengals produced viable sperm as early as the G2 back-cross generation: this is considered rare in the breeding communities, who regularly back-cross early generation females to late generation, fertile hybrid males.[10] The infertility of male F1 Bengals is the reason why all subsequent generations of Bengal cats are characterized by the letter G as opposed to F (acquiring an F2 Bengal would imply two F1 parents which is impossible). As such, the generations of Bengal cats are F1, G2, G3, G4 and so on. [11] Nevertheless, as the term was used incorrectly for many years, many people and breeders still refer to the cats as F2, F3 and F4 even though the term is considered incorrect.

To be considered a domestic Bengal cat by the major cat registries, a Bengal must be at least four generations (G4) or more away from the Asian leopard cat, at which point it is characterized as SBT. [12]

Popularity[]

The Bengal breed was more fully developed by the 1980s. "In 1992 The International Cat Association had 125 registered Bengal Breeders."[3] By the 2000s, Bengals had become a very popular breed. In 2019, there were nearly 2,000 Bengal breeders worldwide.

| Year | TICA registered Bengal Breeders |

|---|---|

| 1992[3] | 125

|

| 2019*[13] | 1,979

|

* The 2019 number only represents the breeders who use the word "Bengals" in their cattery name.

Markings[]

Colors[]

Bengals come in a variety of coat colors.[14][15] The International Cat Association (TICA) recognizes several Bengal colors. Brown Spotted, Seal Lynx Point (snow), Sepia, silver, and Mink Spotted Tabby Bengals.[16]

Spotted Rosetted[]

The Bengal cat is the only domestic breed of cat that has rosette markings.

People most often associate the Bengal with the most popular color: the Brown spotted/rosetted Bengal. However, Bengals have a wide variety of markings and colors. Even within the Brown spotted/rosetted category a Bengal can be: red, brown, black, ticked, grey, spotted, rosetted, clouded. Many people are stunned by the Bengal Cat's resemblance to a leopard. Among domestic cats, the Bengal markings are perhaps the most varied and unique.

Marble[]

Domestic cats have four distinct and heritable coat patterns – ticked, mackerel, blotched, and spotted – these are collectively referred to as tabby markings.[17]

Christopher Kaelin, a Stanford University geneticist, has conducted research which has been used to identify the spotted gene and the marble gene in domestic Bengal cats. Kaelin studied the color and pattern variations of feral cats in Northern California, and was able to identify the gene responsible for the marble pattern in Bengal cats.[18]

Bengal size[]

The Bengal is an average to large-sized, spotted cat breed.[19] Bengals are long and lean. Bengals are larger than the average house cat because of their muscular bodies.

Legal restrictions[]

In the United States, legal restrictions may be in place in cities and states. In New York City and the state of Hawaii, Bengal cats are prohibited by law (as are all other hybrids of domestic and wild cat species).[20][21][22] In various other places, such as Seattle, Washington, and Denver, Colorado, there are limits on Bengal ownership.[23] Bengals of the F1-F4 generations are regulated in New York, Georgia, Massachusetts, Delaware, Connecticut, and Indiana. Except where noted above, Bengal cats with a generation of F5 and beyond are considered domestic, and are generally legal.

Bengals were regulated in the United Kingdom, however the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs removed the previous licensing requirements in 2007.[24]

In Australia F5 Bengals are not restricted, but their import is complex.[25]

Temperament[]

Bengal cats are smart, energetic and playful (though in some rare cases they may be quite lazy). Many Bengal owners say that their Bengal naturally retrieves items, and they often enjoy playing in water.[26]

The International Cat Association (TICA) describes the Bengal cat as an active, inquisitive cat that loves to be up high. Most Bengals enjoy playing, chasing, climbing and investigating. In general, Bengals enjoy action. Bengals are generally confident and curious. [5]

Health[]

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)[]

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a major concern in the Bengal cat breed. This is a disease in which the heart muscle (myocardium) becomes abnormally thick (hypertrophied). A thick heart muscle can make it harder for the cat's heart to pump blood.[27] The only way to determine the suitability of Bengal cats meant for breeding is to have the cat's heart scanned by a cardiologist.

HCM is a common genetic disease in Bengal cats and there is no genetic testing available as of 2018. In the United States, the current practice of screening for HCM involves bringing Bengal cats to a board certified veterinary cardiologist where an echocardiogram is completed. Bengal cats which are used for breeding should be screened annually to ensure that no hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is present. Currently North Carolina State University is attempting to identify genetic markers for HCM in the Bengal Cat.[28]

One study published in the Journal of Internal Veterinary Medicine has claimed the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Bengal cats is 16.7% (95% CI = 13.2–46.5%).[29]

Bengal progressive retinal atrophy (PRA-b)[]

Bengal cats are known to be affected by several genetic diseases, one of which is Bengal progressive retinal atrophy, also known as Bengal PRA or PRA-b. Anyone breeding Bengal cats should carry out this test, since it is inexpensive, noninvasive, and easy to perform. A breeder stating their cats are "veterinarian tested" should not be taken to mean that this test has been performed by a vet: it is carried out by the breeder, outside of a vet office (rarely, if ever, by a vet). The test is then sent directly to the laboratory.

Erythrocyte pyruvate kinase deficiency (PK-deficiency or PK-def)[]

PK deficiency is a common genetic diseases found in Bengal Cats. PK deficiency is another test that is administered by the breeder. Breeding Bengal Cats should be tested before breeding to ensure two PK deficiency carriers are not mated. This is a test that a breeder must do on their own. A breeder uses a cotton swab to rub the inside of the cat's mouth and then mails the swab to the laboratory.

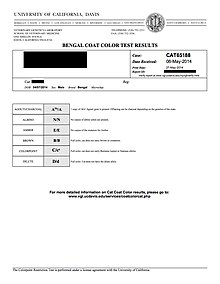

Bengal blood type[]

The UC Davis Veterinary Genetics Laboratory has studied domestic cat blood types. They conclude that most domestic cats fall within the AB system. The common blood types are A and B and some cats have the rare AB blood type. There is a lack of sufficient samples from Bengals, so the genetics of the AB blood group in Bengal cats is not well understood.[30]

One Bengal blood type study which took place in the U.K. tested 100 Bengal cats. They concluded that all 100 of the Bengal cats tested had type A blood.[31]

Responsible Bengal breeding[]

Responsible Bengal breeders learn which recessive genes their breeding cats carry. The most pressing concerns when breeding Bengals are hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), progressive retinal atrophy and pyruvate kinase deficiency. Cat breeders must be aware of all current breed specific testing. Bengal breeders should do all available testing to ensure they are not breeding cats with health problems.

HCM screening is a topic which Bengal breeders may debate. HCM can develop in their Bengal cats at any point in time, including soon after annual HCM screening. It is best practice to screen all Bengal cats used in breeding programs: HCM screening by a cardiologist is the only useful test that exists for Bengals and Bengal breeders in 2019. Responsible and consistent screening makes the breed healthier as breeders seek to eliminate cats that screen positive for HCM.[32]

Shedding and grooming[]

Bengals are often claimed by breeders[33] and pet adoption agencies[34] to be a hypoallergenic breed – one less likely to cause an allergic reaction. The Bengal cat is said to produce lower than average levels of allergens,[34][better source needed] though this has not been scientifically proven as of 2020.

Cat geneticist Leslie Lyons, who runs the University of Missouri's Feline and Comparative Genetics Laboratory, discounts such claims, observing that there is no such thing as a hypoallergenic cat. Alleged hypoallergenic breeds thus may still produce a reaction among those who have severe allergies.[35]

Bengal Longhair (Cashmere Bengal)[]

Some long-haired Bengals (more properly, semi-long-haired) have always occurred in Bengal breeding. Many different domestic cats were used to create the Bengal breed, and it is theorized that the gene for long hair came from one from these backcrossings. UC Davis has developed a genetic test for long hair so that Bengal breeders could select Bengal cats with a recessive long-hair gene for their breeding programs.[36]

Some Bengal cats used in breeding can carry a recessive gene for long-haired. When a male and female Bengal each carry a copy of the recessive long hair gene, and those two Bengals are mated with each other, they can produce long-haired Bengals. (See Cat coat genetics#Genes involved in fur length and texture.) In the past, long-haired offspring of Bengal matings were spayed or neutered until some breeders chose to develop the long-haired Bengal (which are sometimes called a Cashmere Bengal)

Long-haired Bengals are starting to gain more recognition in some cat breed registries but are not wildly accepted. Since 2013, they have "preliminary" breed status in the (NZCF) registry, under the breed name Cashmere Bengal.[37][38] Since 2017 The International Cat Association (TICA) has accepted the Bengal Longhair.[39] in competitions.

References[]

- ^ Harrison William Weir, Our Cats and All About Them: Their Varieties, Habits, and Management, (Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1889), p. 55.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hamilton, Denise (March 10, 1994). "A Little Cat Feat: A Covina woman's efforts at cross-breeding wild and domestic felines are paying off handsomely". Los Angeles Times. p. 2. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Jones, Joyce (September 20, 1992). "The Pet Cat That Evokes the Leopard". The New York Times. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Meet The Bengal: The Miniature Leopard of the Cat World". BasePaws.com. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Bengal Breed". TICA.org. The International Cat Association. August 13, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ "The Governing Council of the Cat Fancy". Gccfcats. GCCF. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- ^ "Breed standards". FIFe. FIFe. Archived from the original on December 20, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- ^ "Bengals Take Their First Step in CFA". showcatsonline. Show Cats Online. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Moments in History of ACF". acf.asn.au. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Davis, Brian W.; Seabury, Christopher M.; Brashear, Wesley A.; Li, Gang; Roelke-Parker, Melody; Murphy, William J. (2015). "Creation of Interspecies Domestic Cat Hybrids". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 32 (10): 2534–2546. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv124. PMC 4592343. PMID 26006188.

- ^ "From F to G for Better Understanding". Bengal Cats. April 29, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ "Asian Leopard Cat Cross to Bengal, Prionailurus Bengalensis". Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ "TICA Registered Cattery Names". TICA.org. The International Cat Association. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ "Bengal Breed". Tica.org. The International Cat Association. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ "So, Do You Think My Cat Is a Bengal?". WildcatSanctuary.org. Sandstone, Minnesota: Wildcat Sanctuary. 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Brown, Alan. "Bengal Cats & Kittens". BengalCat.com. The International Cat Association. Retrieved September 12, 2013 – via The International Bengal Cat Society.

- ^ Barsh, Greg; Kaelin, Christopher (2010). "Tabby pattern genetics – a whole new breed of cat". Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 23 (4): 514–516. doi:10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00723.x. PMID 20518859. S2CID 7082692.

- ^ Conger, Krista. "How the cheetah got its stripes: A genetic tale by Stanford researchers". Stanford. Stanford University. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ Wilson, Julia (2019). "Bengal Cat Profile – History, Appearance and Temperament". Cat-World.com. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Saulny, Susan (May 12, 2005). "What's Up, Pussycat? Whoa!". The New York Times. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ "Health Code of the City of New York". Title 24 Environmental Sanitation, Article 161 Animals. Retrieved February 28, 2019 – via Yumpu.com.

- ^ "PQ – Non-domestic Animal and Microorganism Lists". HDOA.Hawaii.gov. State of Hawaii Plant Industry Division. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ Alessio, Kristine C. "Legislation and Your Cat" (PDF). BengalCat.com. The International Bengal Cat Society. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ "The Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976 (Modification) Order 2007". Legislation.gov.uk. November 4, 2014. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ "Guidance on the Import of Live Hybrid Animals". Environment.gov.au. Commonwealth of Australia Department of Environment. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ Jaccard, Laurent (April 8, 2017). "Bengal Cat Behaviors Explained". Bengal Cats. Bengal Cats. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ "Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy". MayoClinic.org. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ Meurs, Kate. "Genetics: Bengal Cat Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Study". CVM.NCSU.edu. College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ Longeri, M.; Ferrari, P.; Knafelz, P.; Mezzelani, A.; Marabotti, A.; Milanesi, L.; Pertica, G.; Polli, M.; Brambilla, P.G.; Kittleson, M.; Lyons, L.A.; Porciello, F. (January 17, 2013). "Myosin-Binding Protein C DNA Variants in Domestic Cats (A31P, A74T, R820W) and their Association with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 27 (2): 275–285. doi:10.1111/jvim.12031. PMC 3602388. PMID 23323744.

- ^ "AB blood group in felines". Veterinary Genetics Laboratory. VGL.UCDavis.edu. University of California, Davis. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Gunn-Moore, Danièlle A. (January 1, 2011). "Feline blood transfusions: A pinker shade of pale". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. Retrieved April 24, 2016.

- ^ Kittleson, Mark. "Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy HCM". BengalsIllustrated.com. Oroville, California: Award Winning Publications. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ See, e.g., this breeder-operated Bengals portal: "Bengal Cats—Are They Hypoallergenic?". BengalsIllustrated.com. Award Winning Publications / The International Bengal Cat Connection. 2012. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dhir, Rajeev. "Suffering From Allergies? You Can Still Adopt a Cat". NECN.com. New England Cable News (NBCUniversal Media). Archived from the original on July 20, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Schmitt, Kristen A. "There's No Such Thing as a Hypoallergenic Cat". SmithsonianMag.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ "Long-Hair Test for Felines". VGL.UCDavis.edu. Veterinary Genetics Laboratory, University of California, Davis. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ "Minutes of Executive Council Meeting, August 2013". . Archived from the original (Microsoft Word) on January 13, 2015. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- ^ "Bengal Cats: Their History, Breeds and Other Facts". zoipet.com. August 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ "TICA cat breeds". The International Cat Association (TICA). Retrieved May 27, 2021.

External links[]

- The International Bengal Cat Society

- Complete Bengal Cat History Archived August 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Bengal Cat Guide

- Bengal Genetics

- About the Bengal

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bengal cats. |

- Cat breeds

- Cat breeds originating in the United States

- Domestic–wild hybrid cats

- Cats