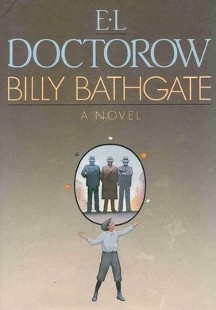

Billy Bathgate

First edition | |

| Author | E. L. Doctorow |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Crime |

| Publisher | Random House |

Publication date | 1989 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 323 pp |

Billy Bathgate is a 1989 novel by author E. L. Doctorow that won the 1989 National Book Critics Circle award for fiction for 1990,[1] the 1990 PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction,[2] the 1990 William Dean Howells Medal,[3] and was the runner-up for the 1990 Pulitzer Prize[4] and the 1989 National Book Award.[5]

A film based on the novel was released in 1991 to very mixed reviews.[6]

Plot summary[]

Billy Behan is an impoverished Irish American fifteen-year-old living in The Bronx with his crazy mother. One afternoon Billy is present when the Jewish mobster Dutch Schultz arrives to inspect a beer warehouse. When Billy demonstrates his skill at juggling, Schultz calls him a "capable boy" and tips him. After he later infiltrates the gang's offices, Schultz's accountant, Otto Berman, begins mentoring Billy, who assumes the surname of Bathgate after a local street.

When Berman tasks Billy to spy on the gangsters who regularly congregate at a nightclub Schultz owns, Billy witnesses one of Schultz's lieutenants, Bo Weinberg, meeting with a pair of men affiliated with the Italian mafia. Schultz then has Weinberg and his girlfriend, a socialite named Drew Preston, kidnapped at gunpoint. Billy follows them out to a riverboat, where he witnesses Schultz getting Weinberg thrown into the East River with his feet encased in cement. Afterwards Schultz has Billy take Drew back to her apartment to get her belongings. There Billy learns that her wealthy husband, Harvey, is a closeted homosexual and that they share a marriage of convenience.

Seeing Schultz as simply the latest of her sexual conquests, Drew agrees to become his gun moll and is taken with him when he settles in Onondaga as part of his plan to avoid conviction for tax evasion. There Billy is represented as Schulz's ward with Drew as his governess, while Schultz uses his money to buy several townspeople out of debt and cements his position within the community by converting to become a member of the local Catholic church. One afternoon, Drew goes for a country hike with Billy and asks him to tell her how Bo died. Afterwards, she scrambles down the side of a waterfall and swims in the pool underneath, where Billy comforts her.

For the sake of appearances, Berman instructs Billy to take Drew to the races at Saratoga Springs while the trial takes place at Onondaga and the two begin an affair. But Billy comes to realize that the real reason Berman sent Drew away was to have her killed, as she has become a liability, so Billy arranges for ostentatious flowers and other gifts to be delivered to Drew's box at the races to draw attention to her. It is now impossible to touch her without being noticed. The ruse buys enough time for Harvey, whom Billy contacted beforehand, to collect her and take her out of the country before the hitmen sent by Schultz can act. Billy meanwhile deflects suspicion from himself by explaining that "rich folk" commonly act on impulse in this way.

After Schultz is acquitted at his trial, federal prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey gives orders to have Schultz arrested if he returns to New York. Schultz flees to Newark and sets up an office in the back room of a chophouse. Against Berman's advice, Schultz decides to assassinate Dewey and orders Billy to shadow his apartment block in order to determine the best time to murder him. Before this can happen, gunmen sent by a rival gang leader storm the chophouse and shoot Schultz, Berman, and their bodyguards. Billy is small enough to escape out of a bathroom window and returns in time for the dying Berman to give Billy the code to Schultz's personal safe. Billy later hides in the hospital room and notes down the delirious Schultz's stream of consciousness monologue as he is dying. Later he uses clues from this to locate Schultz's concealed resources.

The rival leader summons Billy to ask him about the location of Schultz's money, but Billy manipulates him into believing that Schulz's attorney Dixie Davis knows where it is hidden. Billy then returns to the Bronx to care for his mother. Next year Drew's chauffeur arrives at Billy’s new home with an infant son, the product of his and Drew's time in Saratoga Springs. Now a father, and financed with the contents of Schultz's safe, Billy gets himself an education and takes part in World War II. It is only on his return that he retrieves Schultz's larger fortune to gain an undisclosed renown for himself.

The novel[]

Billy Bathgate is the eighth in a series of what critic James Wood has called "intricate historical brocades". Earlier novels by Doctorow that were also set in the 1930s include Loon Lake and World's Fair; the latter also shares poetical evocations of the Bronx in which the author himself grew up. Doctorow has described his novel as "a young man's sentimental education in the tribal life of gangsters".[7] A reviewer saw in it "Doctorow’s shapeliest piece of work: a richly detailed report of a 15-year-old boy's journey from childhood to adulthood".[8]

In a radio broadcast, Doctorow described the novel's genesis in a picture, whose origin he could no longer remember, of men in tuxedos and black tie on a tugboat. Trying to interpret that image prompted him to ponder "the culture of gangsterism" and its mythic appeal. The novel leads off with Billy's description of Bo Weinberg's execution (before backtracking to account for how he got there): a performance of which Doctorow explained that "the very first sentence I wrote in Billy Bathgate is the first sentence that appears in the book, and it actually delivered the character Billy to me. He was sort of built into the diction and the syntax, and even the rhythm of the sentence gave me the way he breathed".[9] With this as a start, the novel develops into what is largely a first person monologue, less narration than an act of lyrical remembrance.

In fact, the act of speaking and its interpretation is at the heart of the novel. Through paying close attention to the gangster's death-bed ramblings, Billy finds the clue to locate Schultz's hidden treasure. And as he himself describes, such attention also leads to his equally valuable discovery of the verbal means to preserve as a lasting memory the lesson of what is otherwise a purely destructive force. "Whereas Schultz's rage appropriates everything to his need to destroy, Billy's words bear permanent witness to whatever is threatened with impermanence".[10]

While most reviewers responded to Doctorow's verbal dexterity and reinterpretation of historical facts, they found the ending unconvincingly sentimental.[11][12][13] And for one interpreter, at least, the entire plot was grounded in sentimentality, "pure and defiant daydream" based on pulp fiction, its deficiency disguised in a heightened prose that scarcely stops to draw breath and a "vocabulary charged with overkill".[14]

References[]

- ^ "All Past National Book Critics Circle Award Winners and Finalists". National Book Critics Circle. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ "Past Winners & Finalists". PEN/Faulkner Foundation. Archived from the original on 21 December 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ "The William Dean Howells Medal". www.artsandletters.org. American Academy of Arts and Letters. Archived from the original on 2015-03-14. Retrieved 2015-05-08.

- ^ 1990 Pulitzer Prize Nominated Finalists (Runners Up) pulitzer.org Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ "National Book Awards – 1989". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Billy Bathgate, Roger Ebert, 1 November 1991

- ^ Andrew Pulver, "Billygate", The Guardian, 5 June 2004

- ^ Ann Tyler, "An American Boy in Gangland", New York Times, 26 Feb 1989

- ^ "Fresh Air Remembers Billy Bathgate Author E. L. Doctorow", WUWF Live Radio, 24 July 2015

- ^ "Billy Bathgate", Donald E. Pease, America 13 May 1989

- ^ New York Times, 26 Feb. 1989

- ^ Gary Soto, Los Angeles Times, 25 March 1990

- ^ Publishers Weekly 1 Feb. 1989

- ^ Douglas Fowler, Understanding E.L. Doctorow, Univ of South Carolina 1992, pp.144 -60

External links[]

- Organized crime novels

- 1989 American novels

- American crime novels

- American novels adapted into films

- Novels by E. L. Doctorow

- Novels set in New York City

- Random House books

- PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction-winning works

- Cultural depictions of Lucky Luciano

- Cultural depictions of Dutch Schultz

- National Book Critics Circle Award-winning works