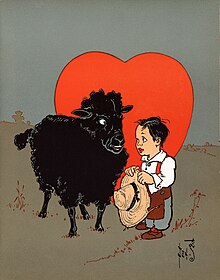

Black sheep

In the English language, black sheep is an idiom used to describe a member of a group, different from the rest, especially within a family, who does not fit in. The term stems from sheep whose fleece is colored black rather than the more common white; these sheep stand out in the flock and their wool was traditionally considered less valuable as it was not able to be dyed.

In large herds, Black sheep are used because they contrast against the landscape better than their white siblings. Usually, one black sheep accompanies 100 white sheep in a flock of 1,000 or more, so that shepherds can easily count a flock

The term has typically been given negative implications, implying waywardness.[1]

In psychology, the black sheep effect refers to the tendency of group members to judge likeable ingroup members more positively and deviant ingroup members more negatively than comparable outgroup members.[2]

Origin[]

This section does not cite any sources. (September 2019) |

In most sheep, a white fleece is not caused by albinism but by a common dominant gene that switches color production off, thus obscuring any other color that may be present. A black fleece is caused by a recessive gene, so if a white ram and a white ewe are each heterozygous for black, in about 25 percent of cases they will produce a black lamb. In fact in most white sheep breeds, only a few white sheep are heterozygous for black, so black lambs are usually much rarer than this.

Idiomatic usage[]

The term originated from the occasional black sheep which are born into a flock of white sheep. Black wool was considered commercially undesirable because it could not be dyed.[1] In 18th and 19th century England, the black color of the sheep was seen as the mark of the devil.[3] In modern usage, the expression has lost some of its negative connotations, though the term is usually given to the member of a group who has certain characteristics or lack thereof deemed undesirable by that group.[4] Jessica Mitford described herself as "the red sheep of the family", a communist in a family of aristocratic fascists.[5]

The idiom is also found in other languages, e.g. German, French, Italian, Serbian, Bulgarian, Hebrew, Portuguese, Bosnian, Greek, Turkish, Hungarian, Dutch, Afrikaans, Swedish, Danish, Spanish, Catalan, Czech, Slovak, Romanian and Polish. During the Second Spanish Republic a weekly magazine named El Be Negre, meaning 'The Black Sheep', was published in Barcelona.[6]

The same concept is illustrated in some other languages by the phrase "white crow": for example, belaya vorona (бе́лая воро́на) in Russian and kalāg-e sefīd (کلاغ سفید) in Persian.

In psychology[]

In 1988, Marques, Yzerbyt and Leyens conducted an experiment where Belgian students rated the following groups according to trait-descriptors (e.g. sociable, polite, violent, cold): unlikeable Belgian students, unlikeable North African students, likeable Belgian students, and likeable North African students. The results indicated that favorability is considered highest for likeable ingroup members and lowest for unlikeable ingroup members, with the favorability of unlikeable and likeable outgroup members lying between the two ingroup members.[2] These extreme judgements of likeable and unlikeable (i.e., deviant) ingroup members, relatively to comparable outgroup members is called "black sheep effect". This effect has been shown in various intergroup contexts and under a variety of conditions, and in many experiments manipulating likeability and norm deviance.[7][8][9][10]

Explanations[]

A prominent explanation of the black sheep effect derives from the social identity approach (social identity theory[11] and self-categorization theory[12]). Group members are motivated to sustain a positive and distinctive social identity and, as a consequence, group members emphasize likeable members and evaluate them more positive than outgroup members, bolstering the positive image of their ingroup (ingroup bias). Furthermore, the positive social identity may be threatened by group members who deviate from a relevant group norm. To protect the positive group image, ingroup members derogate ingroup deviants more harshly than deviants of an outgroup (Marques, Abrams, Páez, & Hogg, 2001).[13]

In addition, Eidelman and Biernat showed in 2003 that personal identities are also threatened through deviant ingroup members. They argue that devaluation of deviant members is an individual response of interpersonal differentiation.[14] Khan and Lambert suggested in 1998 that cognitive processes such as assimilation and contrast, which may underline the effect, should be examined.[9]

Limitations[]

Even though there is wide support for the black sheep effect, the opposite pattern has been found, for example, that White participants judge unqualified Black targets more negatively than comparable White targets (e.g. Feldman, 1972;[15] Linville & Jones, 1980).[16] Consequently, there are several factors which influence the black sheep effect. For instance, the higher the identification with the ingroup, and the higher the entitativity of the ingroup, the more the black sheep effect emerges.[17][18] Even situational factors explaining the deviance have an influence whether the black sheep effect occurs.[19]

See also[]

- Black swan theory

- Glossary of sheep husbandry

- Scapegoat

- Baa Baa Black Sheep

- The Ugly Duckling

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ammer, Christine (1997). American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-395-72774-4. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marques, J. M.; Yzerbyt, V. Y.; Leyens, J. (1988). "The 'Black Sheep Effect': Extremity of judgments towards ingroup members as a function of group identification". European Journal of Social Psychology. 18: 1–16. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420180102.

- ^ Sykes, Christopher Simon (1983). Black Sheep. New York: Viking Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-670-17276-4.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms. Houghton Mifflin Company. 1992. Archived from the original on 2008-04-15. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ "Red Sheep: How Jessica Mitford found her voice" by Thomas Mallon 16 Oct 2007 New Yorker Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ El be negre (1931-1936) - La Ciberniz Archived 2013-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Branscombe, N.; Wann, D.; Noel, J.; Coleman, J. (1993). "In-group or out-group extremity: Importance of the threatened social identity". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 19 (4): 381–388. doi:10.1177/0146167293194003.

- ^ Coull, A.; Yzerbyt, V. Y.; Castano, E.; Paladino, M.-P.; Leemans, V. (2001). "Protecting the ingroup: Motivated allocation of cognitive resources in the presence of threatening ingroup members". Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 4 (4): 327–339. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.379.3383. doi:10.1177/1368430201004004003.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Khan, S.; Lambert, A. J. (1998). "Ingroup favoritism versus black sheep effects in observations of informal conversations". Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 20 (4): 263–269. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp2004_3.

- ^ Pinto, I. R.; Marques, J. M.; Levine, J. M.; Abrams, D. (2010). "Membership status and subjective group dynamics: Who triggers the black sheep effect?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 99 (1): 107–119. doi:10.1037/a0018187. PMID 20565188.

- ^ Worchel, S.; Austin, W. G. (1979). The Social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole.

- ^ Turner, J. C.; Hogg, M. A.; Oakes, P. J.; Reicher, S. D.; Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the Social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

- ^ Hogg, M. A.; Tindale, S. (2001). Blackwell handbook of social psychology: group processes. Malden, Mass: Blackwell.

- ^ Eidelman, S.; Biernat, M. (2003). "Derogating black sheep: Individual or group protection?". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 39 (6): 602–609. doi:10.1016/S0022-1031(03)00042-8.

- ^ Feldman, J. M. (1972). "Stimulus characteristics and subject prejudice as determinants of stereotype attribution". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 21 (3): 333–340. doi:10.1037/h0032313.

- ^ Linville, P. W.; Jones, E. E. (1980). "Polarized appraisals of out-group members". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 38 (5): 689–703. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.38.5.689.

- ^ Castano, E.; Paladino, M.; Coull, A.; Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2002). "Protecting the ingroup stereotype: Ingroup identification and the management of deviant ingroup members". British Journal of Social Psychology. 41 (3): 365–385. doi:10.1348/014466602760344269. PMID 12419008. S2CID 2003883.

- ^ Lewis, A. C.; Sherman, S. J. (2010). "Perceived entitativity and the black-sheep effect: When will we denigrate negative ingroup members?". The Journal of Social Psychology. 150 (2): 211–225. doi:10.1080/00224540903366388. PMID 20397595.

- ^ De Cremer, D.; Vanbeselaere, N. (1999). "I am deviant, because...: The impact of situational factors upon the black sheep effect". Psychologica Belgica. 39: 71–79.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Black sheep. |

| Look up black sheep in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Exploration of the etymology of the phrase "black sheep of the family"

- Marques, José M.; José M. Marques; Vincent Y. Yzerbyt (1988). "The black sheep effect: Judgmental extremity towards ingroup members in inter-and intra-group situations". European Journal of Social Psychology. 18 (3): 287–292. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420180308. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- English-language idioms

- Pejorative terms for people

- Deviance (sociology)

- Sheep

- Metaphors referring to sheep or goats

- Majority–minority relations