Body modification

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

Body modification (or body alteration) is the deliberate altering of the human anatomy or human physical appearance.[1] It is often done for aesthetics, sexual enhancement, rites of passage, religious beliefs, to display group membership or affiliation, in remembrance of lived experience, traditional symbolism such as axis mundi and mythology, to create body art, for shock value, and as self-expression, among other reasons.[1][2] In its broadest definition it includes skin tattooing, socially acceptable decoration (e.g., common ear piercing in many societies), and religious rites of passage (e.g., circumcision in a number of cultures), as well as the modern primitive movement.

Explicit ornaments[]

- Body piercing - permanent placement of jewelry through an artificial fistula; sometimes further modified by stretching

- Ear piercing - the most common type of body modification

- Pearling - also known as genital beading

- Neck ring - multiple neck rings or spiral are worn to stretch the neck (in reality lowering of the shoulders)

- Scrotal implants[3]

- Tattooing - injection of a pigment under the skin

- Teeth blackening[4]

- Eye tattooing - injection of a pigment into the sclera

- Extraocular implant (eyeball jewelry) - the implantation of jewelry in the outer layer of the eye

- Surface piercing - a piercing where the entrance and exit holes are pierced through the same flat area of skin

- Microdermal implants[5][6]

- Transdermal implant - implantation of an object below the dermis, but which exits the skin at one or more points

Subdermal implants[]

- Subdermal implants - implantation of an object that resides entirely below the dermis, including horn implants[7]

Removal or split[]

- Hair cutting

- Hair removal

- Genital modification and mutilation:

- Female genital mutilation

- Clitoral hood reduction - removal of the clitoral hood

- Clitoridectomy - removal of the clitoris

- Infibulation - removal of the external genitalia (and suturing of the vulva)

- Labiaplasty - alteration (removal, reduction, enhancement, or creation) of the labia

- Circumcision - the partial or full removal of the foreskin, sometimes also the frenulum

- Foreskin restoration - techniques for attempting restoration

- Emasculation - complete removal of the penis (orchiectomy plus penectomy)

- Genital frenectomy[8]

- Meatotomy - splitting of the underside of the glans penis

- Orchiectomy - removal of the testicles

- Penectomy - removal of the penis

- Subincision - splitting of the underside of the penis, also called urethrotomy

Nipple cutting:

Nullification involves the voluntary removal of body parts. Body parts that are commonly removed by those practicing body nullification are: penis, testicles, clitoris, labia and nipples. Sometimes people who desire a nullification may be diagnosed with gender dysphoria, body integrity identity disorder or apotemnophilia.[11]

Tongue cutting:

- Lingual frenectomy[12] - this is to expand the external physical protrusion of the tongue.

- Tongue splitting - bisection of the tongue similar to a snake

Applying long-term force[]

Body modifications occurring as the end result of long term activities or practices

- Tightlacing - binding of the waist and shaping of the torso

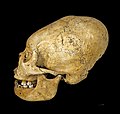

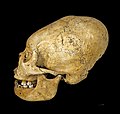

- Cranial binding - modification of the shape of infants' heads, now extremely rare

- Breast ironing - Pressing (sometimes with a heated object) the breasts of a pubescent female to prevent their growth.

- Foot binding - compression of the feet of girls to modify them for aesthetic reasons

- Anal stretching[13]

- Jelqing - penis enlargement with physical exercises by using a milking motion, to enhance girth mainly over a period of two to three months

- Non-surgical elongation of organs by prolonged stretching using weights or spacing devices. Some cultural traditions prescribe for or encourage members of one sex (or both) to have one organ stretched till permanent re-dimensioning has occurred, such as:

- The 'giraffe-like' stretched necks (sometimes also other organs) of women among the Burmese Kayan tribe, the result of wearing brass coils around them. This compresses the collarbone and upper ribs but is not medically dangerous. It is a myth that removing the rings will cause the neck to 'flop'; Padaung women remove them regularly for cleaning etc.

- Stretched lip piercings - achieved by inserting ever larger plates, such as those made of clay used by some Amazonian tribes.

- Labia stretching or pulling to enhance sexual pleasure by stimulation, particularly reaching an orgasm that squirts, multiple orgasms that flow together frequently upon climax.

- Foreskin restoration or stretching to increase its physical size, desensitize the foreskin, move the foreskin further down the head for enhanced sensitivity and improve its appearance.

Others[]

- Human branding - controlled burning or cauterizing of tissue to encourage intentional scarring

- Ear shaping[14] (which includes cropping,[15] ear pointing or "elfing"[16])

- Scarification - cutting or removal of dermis with the intent to encourage intentional scarring or keloiding

- Human tooth sharpening[17] - generally used to have the appearance of some sort of animal.

- Yaeba - the deliberate misaligning or capping of teeth to give a crooked appearance. Popular in Japan.

- Tooth-knocking or tooth ablation - the act of deliberately knocking one's teeth out, often as a rite of passage or to satisfy an aesthetic ideal. Commonly practiced among Australian Aboriginals[18] and Native Hawaiians[19] prior to the 20th century, and observed in archaeological complexes around the world.

Tattooed ankles

Ear piercing and stretching

Proto Nazca modified skull, c 200-100 BC

Subdermal implant

Tongue splitting

Scarification

Mursi woman wearing a lip plate in Ethiopia

Kayan woman with neck rings

Controversy[]

"Disfigurement" and "mutilation" (regardless of any appreciation this always applies objectively whenever a bodily function is gravely diminished or lost) are terms used by opponents of body modification to describe certain types of modifications, especially non-consensual ones. Those terms are used fairly uncontroversially to describe the victims of torture, who have endured damage to ears, eyes, feet, genitalia, hands, noses, teeth, and/or tongues, including amputation, burning, flagellation, piercing, skinning, and wheeling.[citation needed]

Some invasive procedures that modify human genitals are performed with the informed consent of the patient, using anesthesia.[20][21] The phrase "Genital mutilation" is sometimes used to describe procedures that individuals are forced to undergo without their informed consent, or without anesthesia or sterilised surgical tools.[22] The phrase has been applied to involuntary castration, male circumcision, and female genital mutilation. Intersex campaigners say that childhood modification of genitals of individuals with intersex conditions without their informed consent is a form of mutilation.[23]

In many ways self-mutilation is very different than body-modification. Body modification gives one the feeling of pride and excitement, giving one something to show off to others.[24] Alternately, those who self-mutilate typically are ashamed of what they've done and want to hide any evidence of harm. Body modification is explored for adornment, self-expression, and an array of many other positive reasons, while self-mutilation is inflicted because of mental or emotional stress and the inability to cope with psychological pain. Those who self-mutilate do so in order to punish themselves, express internal turmoil, and reduce severe anxiety.[25]

Individuals known for extensive body modification[]

Cybernetic biohacking[]

- Kevin Warwick, a scientist nicknamed "Captain Cyborg" by The Register,[26] in 1998 became the first human to experiment with a RFID transmitter implant. He followed that up in 2002 by having a 100 electrode array implanted in his nervous system.[27] A simpler array was implanted into the arm of Warwick's wife, with the ultimate aim of one day creating a form of telepathy or empathy using the Internet to communicate the signal over long distances. This experiment resulted in the first direct and purely electronic communication between the nervous systems of two humans.[28]

Piercing[]

- Elaine Davidson is the "Most Pierced Woman" according to the Guinness World Records. On 9 August 2001 when she was examined by a Guinness official she was found to have 720 piercings.[29] She has continued to add to her piercings and as of 2019 reports having a total of 1103.[30]

Tattooing[]

- Lucky Diamond Rich, holds the Guinness world record as "the world's most tattooed person" as of 2006.[31] He has held the certified record since 2006, being 100 percent tattooed.[32][33]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thompson, Tim; Black, Sue (2010). Forensic Human Identification: An Introduction. CRC Press. pp. 379–398. ISBN 978-1420005714. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "What Is Body Modification?". Essortment. 16 May 1986. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Scrotal Implant". Archived from the original on 21 January 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Thomas Zumbroich". oxford.academia.edu.

- ^ "Microdermal". Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Dermal Anchoring". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Horn Implant". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Genital Frenectomy". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Nipple Removal". Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Nipple Splitting". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Jamie Gadette. "Underground". Salt Lake City Weekly. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ^ "Tongue Frenectomy". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Ear Shaping". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Ear Cropping". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Ear Pointing". Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Tooth Filing". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Australian Aboriginal Rites of Passage". www.webpages.uidaho.edu.

- ^ "Journal of the Polynesian Society: Tooth Ablation In Old Hawai'i, By Michael Pietrusewsky And Michele T. Douglas, P 255-272". www.jps.auckland.ac.nz.

- ^ John R. Holman-Keith A. Stuessi. "Adult Circumcision".

- ^ https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/malecircumcision/who_mc_local_anaesthesia.pdf

- ^ Hellsten, SK (June 2004). "Rationalising circumcision: from tradition to fashion, from public health to individual freedom—critical notes on cultural persistence of the practice of genital mutilation". J Med Ethics. 30 (3): 248–53. doi:10.1136/jme.2004.008888. PMC 1733870. PMID 15173357.

- ^ Wilchins, Riki. "A Girl's Right to Choose: Intersex Children and Parents Challenge Narrow Standards of Gender". NOW Times. National Organization for Women. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ^ "Bradley University: Body Modification & Body Image". www.bradley.edu. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ^ "Self-injury/cutting Causes - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ^ "Search results for "Captain Cyborg"". search.theregister.com.

- ^ Warwick, K.; Gasson, M.; Hutt, B.; Goodhew, I.; Kyberd, P.; Andrews, B.; Teddy, P.; Shad, A. (2003). "The Application of Implant Technology for Cybernetic Systems". Archives of Neurology. 60 (10): 1369–73. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.10.1369. PMID 14568806.

- ^ Warwick, K.; Gasson, M.; Hutt, B.; Goodhew, I.; Kyberd, P.; Schulzrinne, H.; Wu, X. (2004). "Thought Communication and Control: A First Step using Radiotelegraphy". IEE Proceedings - Communications. 151 (3): 185. doi:10.1049/ip-com:20040409.

- ^ "Guinness World Records - Human Body - Extreme Bodies - Most Pierced Woman". Guinness World Records. 9 August 2001. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ "Home Page". Elaine Davidson.

- ^ Guinness World Records. "Most Tattooed Person". Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- ^ Guinness World Records. "Most Tattooed Person". Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Totaro, Paola (16 December 2004). "Sydney's Lucky Diamond". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Body modification

- Cultural trends

- Underground culture