Torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a powerless victim. To be considered torture, the treatment must be inflicted for a specific purpose, such as forcing the victim to confess, provide information, or to punish them.

Torture has been carried out or sanctioned by individuals, groups, and states throughout history from ancient times to modern day, and forms of torture can vary greatly in duration from only a few minutes to several days or longer. Reasons for torture can include punishment, revenge, extortion, persuasion, political re-education, deterrence, coercion of the victim or a third party, interrogation to extract information or a confession irrespective of whether it is false, or simply the sadistic gratification of those carrying out or observing the torture.[1] Some individuals derive intense sexual pleasure from torturing others or being tortured themselves, either literally or in elaborate fantasies.[2] Alternatively, some forms of torture are designed to inflict psychological pain or leave as little physical injury or evidence as possible while achieving the same psychological devastation. The torturer may or may not kill or injure the victim, but torture may result in a deliberate death and serves as a form of capital punishment. Depending on the aim, even a form of torture that is intentionally fatal may be prolonged to allow the victim to suffer as long as possible (such as half-hanging). In other cases, the torturer may be indifferent to the condition of the victim.

Although torture is sanctioned by some states, it is prohibited under international law and the domestic laws of most countries. Although widely illegal and reviled, there is an ongoing debate as to what exactly is and is not legally defined as torture. It is a serious violation of human rights, and is declared to be unacceptable (but not illegal) by Article 5 of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Signatories of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the Additional Protocols I and II of 8 June 1977 officially agree not to torture captured persons in armed conflicts, whether international or internal. Torture is also prohibited for the signatories of the United Nations Convention Against Torture, which has 163 state parties.[3]

National and international legal prohibitions on torture derive from a consensus that torture and similar ill-treatment are immoral, as well as impractical, and information obtained by torture is less reliable than that obtained by other techniques.[4][5][6] Despite these findings and international conventions, organizations that monitor abuses of human rights (e.g., Amnesty International, the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims, Freedom from Torture, etc.) report widespread use condoned by states in many regions of the world.[7] Amnesty International has estimated that 141 countries carried out torture between 2009 and 2013.[8]

Definitions[]

According to the United Nations Convention against Torture, torture is defined as the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a powerless victim. The treatment must be inflicted for a specific purpose, such as forcing the victim to confess, provide information, or to punish them.[9] In general, torture is inflicted in order to break the victim's will.[10] Exactly what that means in practice, and what methods can be considered torture, has been disputed.[11]

History[]

In the study of the history of torture, some authorities rigidly divide the history of torture per se from the history of capital punishment, while noting that most forms of capital punishment are extremely painful. Torture grew into an ornate discipline, where calibrated violence served two functions: to investigate and produce confessions and to attack the body as a form of punishment. Entire populaces of towns would show up to witness an execution by torture in the public square. Those who had been "spared" torture were commonly locked barefooted into the stocks, where children took delight in rubbing feces into their hair and mouths.[12]

Deliberately painful methods of torture and execution for severe crimes were taken for granted as part of justice until the development of Humanism in 17th-century philosophy, and "cruel and unusual punishment" came to be denounced in the English Bill of Rights of 1689. The Age of Enlightenment in the Western world further developed the idea of universal human rights. The adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 marks the recognition at least nominally of a general ban of torture by all UN member states.[citation needed]

Antiquity[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014) |

Judicial torture was probably first applied in Persia, either by Medes or Achaemenid Empire. Prisoners of war had their tongues torn out and were flayed or burned alive. This served the tangential objective of persuading the next city to surrender without a struggle. Over time torture has been used as a means of reform, inducing public terror, interrogation, spectacle, and sadistic pleasure. The ancient Greeks and Romans used torture for interrogation. Until the 2nd century AD, torture was used only on slaves (with a few exceptions).[13] After this point it began to be extended to all members of the lower classes.[14] A slave's testimony was admissible only if extracted by torture, on the assumption that slaves could not be trusted to reveal the truth voluntarily. This torture occurred to break the bond between a master and his slave. Slaves were thought to be incapable of lying under torture.[15]

Middle Ages[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2011) |

Medieval and early modern European courts used torture, depending on the crime of the accused and his or her social status. Torture was deemed a legitimate means to extract confessions or to obtain the names of accomplices or other information about a crime, although many confessions were greatly invalid due to the victim being forced to confess under great agony and pressure. It was permitted by law only if there was already half-proof against the accused.[16] Torture was used in continental Europe to obtain corroborating evidence in the form of a confession when other evidence already existed.[17] Often, defendants already sentenced to death would be tortured to force them to disclose the names of accomplices. Torture in the Medieval Inquisition began in 1252 with a papal bull Ad Extirpanda and ended in 1816 when another papal bull forbade its use. Although the torture that was sanctioned by the bull was less severe than the torture that could be found in contemporary secular courts.

A highly esteemed torture in the times of the Inquisition as a good means of interrogating "taciturn" heretics and wizards was the interrogation chair.[18]

Torture was usually conducted in secret, underground dungeons. By contrast, torturous executions were typically public, and woodcuts of English prisoners being hanged, drawn and quartered show large crowds of spectators, as do paintings of Spanish auto-da-fé executions, in which heretics were burned at the stake. Torture was also used during this period as a means of reform, spectacle, to induce fear into the public, and most popularly as a punishment for treason.

Medieval torture devices were varied. One old English chronicle from the Early Medieval period reads, "They hanged them by the thumbs, or by the head, and hung fires on their feet; they put knotted strings about their heads and writhed them so that it went to the brain ... Some they put in a chest that was short, and narrow, and shallow, and put sharp stones therein, and pressed the man therein so that they broke all his limbs ... I neither can nor may tell all the wounds or all the tortures which they inflicted on wretched men in this land."[19] Tortures later in the Middle Ages consisted of whipping; the crushing of thumbs, feet, legs, and heads in iron presses; burning the flesh; and tearing out teeth, fingernails, and toenails with red-hot iron forceps. Limb-smashing and drowning were also popular medieval tortures. Specific devices were also created and used during this time, including the rack, the Pear (also mentioned in Grose's Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1811) as " [sic.] Pears," and described as being "formerly used in Holland"), thumbscrews, animals like rats, the iron chair, and the cat o nine tails.[20]

However, remains of an Anglo-Saxon ostracized girl aged between 15 and 18 years old, dated back to between 776 and 899 AD, were discovered in Basingstoke in the 1960s, which showed evidence of facial disfigurement, including a cut across her mouth that removed her lips, a cut that had her nose cut off, and another cut across her forehead; such punishments were also related to adulteresses and to slaves caught stealing.[21]

Early modern period[]

During the early modern period, the torture of witches took place. In 1613, Anton Praetorius described the situation of the prisoners in the dungeons in his book Gründlicher Bericht Von Zauberey und Zauberern (Thorough Report about Sorcery and Sorcerers). He was one of the first to protest against all means of torture.

While secular courts often treated suspects ferociously, Will and Ariel Durant argued in The Age of Faith that many of the most vicious procedures were inflicted upon pious heretics by even more pious friars. The Dominicans gained a reputation as some of the most fearsomely innovative torturers in medieval Spain.[22]

Torture was continued by Protestants during the Renaissance against teachers who they viewed as heretics. In 1547 John Calvin had Jacques Gruet arrested in Geneva, Switzerland. Under torture he confessed to several crimes including writing an anonymous letter left in the pulpit which threatened death to Calvin and his associates.[23] The Council of Geneva had him beheaded with Calvin's approval.[24][25][26][27] Suspected witches were also tortured and burnt by Protestant leaders, though more often they were banished from the city, as well as suspected spreaders of the plague, which was considered a more serious crime.[28]

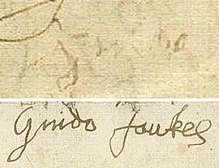

In England the trial by jury developed considerable freedom in evaluating evidence and condemning on circumstantial evidence, making torture to extort confessions unnecessary. For this reason, in England, a regularized system of judicial torture never existed and its use was limited to political cases. Torture was in theory not permitted under English law, but in Tudor and early Stuart times, under certain conditions, torture was used in England. For example, the confession of Marc Smeaton at the trial of Anne Boleyn was presented in written form only, either to hide from the court that Smeaton had been tortured on the rack for four hours, or because Thomas Cromwell was worried that he would recant his confession if cross-examined. When Guy Fawkes was arrested for his role in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 he was tortured until he revealed all he knew about the plot. This was not so much to extract a confession, which was not needed to prove his guilt, but to extract from him the names of his fellow conspirators. By this time torture was not routine in England and a special warrant from King James I was needed before he could be tortured. The wording of the warrant shows some concerns for humanitarian considerations, specifying that the severity of the methods of interrogation were to be increased only gradually until the interrogators were sure that Fawkes had told all he knew.

The privy council attempted to have John Felton who stabbed George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham to death in 1628 questioned under torture on the rack, but the judges resisted, unanimously declaring its use to be contrary to the laws of England.[29] Torture was abolished in England around 1640 (except peine forte et dure, which was abolished in 1772).

In Colonial America, women were sentenced to the stocks with wooden clips on their tongues or subjected to the "dunking stool" for the gender-specific crime of talking too much.[30] Certain Native American peoples, especially in the area that later became the eastern half of the United States, engaged in the sacrificial torture of war captives.[31] And Spanish colonial officials in what is today the southwestern United States and northern Mexico often resorted to torture to extract confessions from rebellious Native Americans, as evidenced by the case of the Pima leader Joseph Romero 'Canito' in 1686.[32]

In the 17th century, the number of incidents of judicial torture decreased in many European regions. in 1624 published Tribunal Reformation, a case against torture. Cesare Beccaria, an Italian lawyer, published in 1764 "An Essay on Crimes and Punishments", in which he argued that torture unjustly punished the innocent and should be unnecessary in proving guilt. Voltaire (1694–1778) also fiercely condemned torture in some of his essays.

While in Egypt in 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte wrote to Major-General Berthier regarding the validity of torture as an interrogation tool:[33]

The barbarous custom of whipping men suspected of having important secrets to reveal must be abolished. It has always been recognized that this method of interrogation, by putting men to the torture, is useless. The wretches say whatever comes into their heads and whatever they think one wants to believe. Consequently, the Commander-in-Chief forbids the use of a method which is contrary to reason and humanity.

European states abolished torture from their statutory law in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. England abolished torture in about 1640 (except peine forte et dure, which England only abolished in 1772), Scotland in 1708, Prussia in 1740, Denmark around 1770, Russia in 1774, Austria and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1776, Italy in 1786, France in 1788, and Baden in 1831.[34][35][36] Sweden was the first to do so in 1722 and the Netherlands did the same in 1798. Bavaria abolished torture in 1806 and Württemberg in 1809. In Spain, the Napoleonic conquest put an end to torture in 1808. Norway abolished it in 1819 and Portugal in 1826. The last European jurisdictions to abolish legal torture were Portugal (1828) and the canton of Glarus in Switzerland (1851).[37]

Since 1948[]

Modern sensibilities have been shaped by a profound reaction to the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the Axis Powers and Allied Powers in the Second World War, which have led to a sweeping international rejection of most if not all aspects of the practice.[38] Even as many states engage in torture, few wish to be described as doing so, either to their own citizens or to the international community. A variety of devices bridge this gap, including state denial, "secret police", "need to know", a denial that given treatments are torturous in nature, appeal to various laws (national or international), the use of jurisdictional argument and the claim of "overriding need". Throughout history and today, many states have engaged in torture, albeit unofficially. Torture ranges from physical, psychological, political, interrogations techniques, and also includes rape of anyone outside of law enforcement.[39]

According to scholar Ervand Abrahamian, although there were several decades of prohibition of torture that spread from Europe to most parts of the world, by the 1980s, the taboo against torture was broken and torture "returned with a vengeance," propelled in part by television and an opportunity to break political prisoners and broadcast the resulting public recantations of their political beliefs for "ideological warfare, political mobilization, and the need to win 'hearts and minds.'"[40]

In the years 2004 and 2005, over 16 countries were documented using torture.[41] In an attempt to bring global awareness, Human Rights Watch has created an internet site to alert people to news and multimedia publications about torture occurring worldwide.[41] The International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims [IRCT] made a global analysis of torture based on [Amnesty International, 2001], [Human Rights Watch, 2003], [United Nations, 2002], [U.S. Department of State, 2002] yearly human rights reports. These reports showed that torture and ill-treatment are consistently report based on all four sources in 32 countries. At least two reports the use of torture and ill-treatment in at least 80 countries. These reports confirm the assumption that torture occurs in a quarter of the world's countries on a regular basis. This global prevalence of torture is estimated on the magnitude of particular high-risk groups and the amount of torture used by these groups. "Such groups comprise refugees and persons who are or have been under torture."[39] According to professor Darius Rejali, although dictatorships may have used tortured "more, and more indiscriminately", it was modern democracies, "the United States, Britain, and France" who "pioneered and exported techniques that have become the lingua franca of modern torture: methods that leave no marks."[42] The practice of torture used as the oppression against political opponents or could be a part of a criminal investigation or interrogation techniques in order to obtain the desired information and keep law enforcement empowered over everyday citizens.[39]

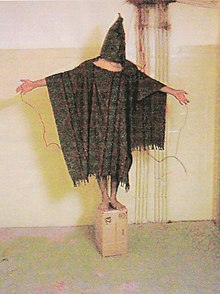

Torture still occurs in a small number[citation needed] of liberal democracies despite several international treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the UN Convention Against Torture making torture illegal. Despite such international conventions, torture cases continue to arise such as the 2004 Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse scandal committed by personnel of the United States Army. The U.S. Constitution and U.S. law prohibits the use of torture, yet such human rights violations occurred during the War on Terror under the euphemism Enhanced interrogation. The United States revised the previous torture policy in 2009 under the Obama Administration. This revision revokes Executive Order 13440 of 20 July 2007, under which the incident at Abu Ghraib and prisoner abuse occurred. Executive Order 13491 of 22 January 2009 further defines United States policy on torture and interrogation techniques in an attempt to further prevent another torture incident.[43] Yet apparently the practice continues, albeit outsourced.[44]

Laws against torture[]

The prohibition of torture is a peremptory norm in public international law—meaning that it is forbidden under all circumstances.[45] On 10 December 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Article 5 states, "No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment."[46] Since that time, a number of other international treaties have been adopted to prevent the use of torture. The most notable treaties relating to torture are the United Nations Convention Against Torture and the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols I and II of 8 June 1977.[47]

Municipal law[]

States that ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture have a treaty obligation to include the provisions into municipal law. The laws of many states therefore formally prohibit torture. However, such de jure legal provisions are by no means a proof that, de facto, the signatory country does not use torture. To prevent torture, many legal systems have a right against self-incrimination or explicitly prohibit undue force when dealing with suspects.

The French 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, of constitutional value, prohibits submitting suspects to any hardship not necessary to secure his or her person.

The U.S. Constitution and U.S. law prohibits the use of unwarranted force or coercion against any person who is subject to interrogation, detention, or arrest. The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution includes protection against self-incrimination, which states that "[n]o person...shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself". This serves as the basis of the Miranda warning, which U.S. law enforcement personnel issue to individuals upon their arrest. Additionally, the U.S. Constitution's Eighth Amendment forbids the use of "cruel and unusual punishments," which is widely interpreted as prohibiting torture. Finally, 18 U.S.C. § 2340[48] et seq. define and forbid torture committed by U.S. nationals outside the United States or non-U.S. nationals who are present in the United States. As the United States recognizes customary international law, or the law of nations, the U.S. Alien Tort Claims Act and the Torture Victim Protection Act also provides legal remedies for victims of torture outside of the United States. Specifically, the status of torturers under the law of the United States, as determined by a famous legal decision in 1980, Filártiga v. Peña-Irala, 630 F.2d 876 (2d Cir. 1980), is that, "the torturer has become, like the pirate and the slave trader before him, hostis humani generis, an enemy of all mankind."[49]

Purpose[]

Punishment[]

Torture for punishment dates back to antiquity and is still employed in the 21st century.[50][51]

Confession[]

Judicial torture for the purpose of eliciting a confession has been used in antiquity and was common in pre-modern society, to the point that it is difficult to find a pre-modern state that did not use torture (against the accused, witnesses, and sometimes the plaintiff) in criminal cases. In Europe, torture was used less after a reduction in the expected level of proof to obtain a conviction, such that it was no longer necessary to torture for a confession. At the same time, improvements in investigation methods may have played a role in making torture obsolete.[52] It continues to be used, especially in judicial systems placing high value on confession in criminal matters, or the state desires to persuade the population that torture victims forced to falsely confess are actually guilty.[53]

Under international law, a confession obtained under torture is not admissible in criminal proceedings.[54]

Interrogation[]

Torture has been used throughout history for the purpose of obtaining information in interrogation, although there is limited information available to scientists on its effectiveness.[55] Neuroscientist Shane O'Mara found that "The evidence all points in the same direction: extreme stressors of the type used during torture impair cognition, memory, and mood in all of their phases." He states that information obtained from torture has historically been false or unreliable, while more accurate interrogation methods exist.[56] The question of effectiveness of torture for interrogation is separate from discussion of whether it is effective for other uses.[57][58]

Public opinion on the use of torture for interrogation varies widely, with the lowest support recorded in West European countries and the highest support found in Africa among 31 countries surveyed between 2006 and 2008. The highest support was found in Turkey and South Korea where a majority of respondents supported the use of torture for interrogation.[59] A study by Jeremy D. Mayer, Naoru Koizumi, and Ammar Anees Malik found that opposition to the usage of torture in interrogation was correlated with stronger political rights but not economic development or the threat of terrorism.[60]

State terrorism[]

Torture may also be used indiscriminately in detention sites for the purpose of terrorizing people other than the direct victim or deterring opposition to the government.[61]

Methods and devices[]

Psychological torture uses non-physical methods that cause psychological suffering. Its effects are not immediately apparent unless they alter the behavior of the tortured person. Since there is no international political consensus on what constitutes psychological torture, it is often overlooked, denied, and referred to by different names.[63]

Psychological torture is less well known than physical torture and tends to be subtle and much easier to conceal. In practice, the distinctions between physical and psychological torture are often blurred.[64] Physical torture is the inflicting of severe pain or suffering on a person. In contrast, psychological torture is directed at the psyche with calculated violations of psychological needs, along with deep damage to psychological structures and the breakage of beliefs underpinning normal sanity. Torturers often inflict both types of torture in combination to compound the associated effects.[citation needed]

Psychological torture also includes deliberate use of extreme stressors and situations such as mock execution, shunning, violation of deep-seated social or sexual norms and taboos, or extended solitary confinement. Because psychological torture needs no physical violence to be effective, it is possible to induce severe psychological pain, suffering, and trauma with no externally visible effects.[citation needed]

Rape and other forms of sexual abuse are often used as methods of torture for interrogative or punitive purposes.[65]

In medical torture, medical practitioners use torture to judge what victims can endure, to apply treatments that enhance torture, or act as torturers in their own right. Josef Mengele and Shirō Ishii were infamous during and after World War II for their involvement in medical torture and murder. In recent years, however, there has been a push to end medical complicity in torture through both international and state-based legal strategies, as well as litigations against individual physicians.[66]

Pharmacological torture is the use of drugs to produce psychological or physical pain or discomfort. Tickle torture is an unusual form of torture which nevertheless has been documented, and can be both physically and psychologically painful.[67][68][69][70]

Widely used in the modern era, prison torture has also become a way of oppression, particularly in the Middle East. Egypt, Iran, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia have operated detention centers in which the inmates were physically and psychologically tortured using electric shocks, isolation, beatings, threats of rape, and other techniques.[71] [72] [73] The UAE has also operated secret prisons in Yemen, where it was involved in a proxy war. Abuse and torture in these prisons were normal. Detainees were tied to a spit and roasted in a circle of fire.[74] From 18 of these clandestine lockups, the Al Munawara Central Prison in Mukalla City kept at least 27 individuals in detention, even when 13 of them had been granted acquittals and 11 had completed their full sentences.[75]

Prevention and opposition[]

International organizations dedicated to the include the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and the United Nations Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture. Also, the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture requires state parties to establish National Preventive Mechanisms. These organizations work to prevent torture by visiting detention sites to provide scrutiny of possible abuses.[76][77]

According to the findings of Dr. Christian Davenport of the University of Notre Dame, Professor William Moore of Florida State University, and David Armstrong of Oxford University during their torture research, evidence suggests that non-governmental organizations have played the most determinant factor for stopping torture once it gets started.[78] Preliminary research suggests that it is civil society, not government institutions, that can stop torture once it has begun. This inability to control abuse and torture in society creates an imperfect Democracy non-compliant with internationally agreed-upon standards for civil and political rights.[39]

In the 21st century, even when states sanction their interrogation methods, torturers often work outside the law. For this reason, some prefer methods that, while unpleasant, leave victims alive and unmarked. A victim with no visible damage may lack credibility when telling tales of torture, whereas a person missing fingernails or eyes can easily prove claims of torture. Mental torture, however, can leave scars just as deep and long-lasting as physical torture.[79] Professional torturers in some countries have used techniques such as electrical shock, asphyxiation, heat, cold, noise, and sleep deprivation, which leave little evidence. However, the most common and prevalent form of torture worldwide[when?] in both developed and under-developed countries is beating.[80]

Effects[]

Common effects of torture on the victim include chronic pain, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and adjustment difficulties, although many survivors' symptoms do not align well with diagnostic categories.[81] It continues to be debated whether PTSD diagnosis is a good fit for torture survivors or if torture results in unique problems.[81] Torture victims often feel guilt and shame, triggered by the humiliation they have endured. Many feel that they have betrayed themselves or their friends and family. All such symptoms are normal human responses to abnormal and inhuman treatment.[82] Current circumstances, such as the uncertainty of applying for asylum in a safe country, strongly impact survivors' well being.[81] Compared to survivors of other forms of trauma, torture survivors experience more post-traumatic growth, more resilience, and better adjustment, but were less physically healthy.[83]

The physical and mental after-effects of torture often place great strain on the entire family and society. Children are particularly vulnerable. They often suffer from feelings of guilt or personal responsibility for what has happened.[84] In some instances, whole societies can be more or less traumatized where torture has been used in a systematic and widespread manner. In general, after years of repression, conflict and war, regular support networks and structures have often been broken or destroyed.[84]

The most common form of forensic identification of past torture is through skin lesions.[85] However, not all torture methods leave physical scars; non-scarring methods such as rape or other sexual assault, waterboarding, or psychological torture may be chosen by states that deny their responsibility for torture.[86]

Rehabilitation[]

Survivors of torture, their families, and others in the community may require long-term material, medical, psychological and social support.[84] Anti torture groups recommend a coordinated effort that covers both physical and psychological aspects, including the patients' needs, problems, expectations, views, and cultural references.[84] Rehabilitation centres around the world, notably the members of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims, commonly offer multi-disciplinary support and counselling, including medical attention / psychotherapeutic treatment, psychosocial support/trauma treatment, legal services and redress, and social reintegration. In the case of asylum seekers and refugees, the services may also include assisting in the documentation of torture for the asylum decision, language classes and help in finding somewhere to live and work.[84]

References[]

- ^ California Penal Code Section 206: The Crime of 'Torture' in California Law, https://www.losangelescriminallawyer.pro/california-penal-code-section-206-pc-torture.html.

- ^ Beers, Mark H., & Berkow, Robert, The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, Kenilworth, NJ: Merck & Co., 1999.

- ^ "United Nations Treaty Collection". United Nations. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Torture and Ill-Treatment in the 'War on Terror'". Amnesty International. 1 November 2005. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ "General Says Less Coercion of Captives Yields Better Data" NY Times 7 September 2004

- ^ David Rose (16 December 2008) "Reckoning" Vanity Fair. Retrieved on 7 June 2009.

- ^ Amnesty International Report 2005 Report 2006

- ^ "Why Amnesty thinks torture should be abolished everywhere". www.amnesty.org. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ Nowak, Manfred (2006). "What Practices Constitute Torture?: US and UN Standards". Human Rights Quarterly. 28 (4): 809–841. doi:10.1353/hrq.2006.0050. ISSN 0275-0392. JSTOR 20072769. S2CID 144007750.

- ^ Miller, Seumas (2017). "Torture". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Michael W. (2010). "A Dark Descent into Reality: Making the Case for an Objective Definition of Torture". Washington and Lee Law Review. 67: 77.

- ^ G. R. Scott, A History of Torture (London: Merchant, 1995).

- ^ Pliny the Younger. Epistulae : X.96.5: "Hunc abstinentia sanctitate, quoad viridis aetas, vicit et fregit; novissime cum senectute ingravescentem viribus animi sustinebat, cum quidem incredibiles cruciatus et indignissima tormenta pateretur."

- ^ de Ste. Croix, Geoffrey Ernst Maurice. Christian Persecution, Martyrdom, and Orthodoxy. 2006. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Peters, Edward. Torture. New York: Basil Blackwell Inc., 1985.

- ^ J. Franklin, The Science of Conjecture: Evidence and Probability Before Pascal. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001, 26–30.

- ^ Langbein, John H., "Torture and Plea Bargaining" (1978). Faculty Scholarship Series. Paper 543. http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/543

- ^ "Please visit our colleagues in Bruges!". torturemuseumamsterdam.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- ^ Bately, Janet M. (1986). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: A Collaborative Edition. Vol. 3: MS. A. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-103-0.

- ^ 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue.

- ^ "An Anglo-Saxon girl had her nose and lips cut off as punishment, an ancient skull shows". CNN. 30 September 2020.

- ^ "Torture and Impunity". EIIR. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Monter, E. William (1973). "Crime and Punishment in Calvin's Geneva, 1562". Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte. 64: 282.

- ^ Parker, T.H.L. (2006). John Calvin: A Biography. Oxford: Lion Hudson plc. ISBN 978-0-7459-5228-4.

- ^ Owen, Robert Dale (1872). The debatable Land Between this World and the Next. New York: G.W. Carleton & Co. p. 69, notes.

- ^ Calvin to William Farel, 20 August 1553, Bonnet, Jules (1820–1892) Letters of John Calvin, Carlisle, Penn: Banner of Truth Trust, 1980, pp. 158–159. ISBN 0-85151-323-9.

- ^ Marshall, John (2006). John Locke, Toleration and Early Enlightenment Culture. Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-521-65114-1.

- ^ Levack, Brian P. (1992). Anthropological Studies of Witchcraft, Magic, and Religion. Vol 1 of Articles on Witchcraft, Magic, and Demonology. Garland.

- ^ Jardine, David (1837). A Reading on the Use of Torture in the Criminal Law of England. London: Baldwin and Cradock. pp. 10–12.

- ^ Brizendine, Louann The Female Brain Broadway Books. New York. 2006 pg 36

- ^ See Captives in American Indian Wars

- ^ Daughters, Anton (28 August 2014). "Torture in Colonial Spain's Northwestern Frontier: The Case of Joseph Romero "Canito," 1686". Journal of the Southwest. 56 (2): 233–251. doi:10.1353/jsw.2014.0009. S2CID 109386502.

- ^ Napoleon Bonaparte, Letters and Documents of Napoleon, Volume I: The Rise to Power, selected and translated by John Eldred Howard (London: The Cresset Press, 1961), 274.

- ^ History of the Christian Church, Volume IV: Mediaeval Christianity. A.D. 590–1073. Chapter VI. Morals And Religion: Page 80:The Torture Archived 14 August 2004 at the Wayback Machine by Schaff, Philip (1819–1893)

- ^ Hutchinson's Encyclopaedia: Torture Archived 7 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Williams, James (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 78.

- ^ Peters, Edward (October 1996). Torture. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0812215991.

- ^ Elihu Lauterpacht, C. J. Greenwood International Law Reports, Cambridge University Press, 2002 ISBN 0-521-66122-6, ISBN 978-0-521-66122-5 p. 139 section 189

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Broken Spirits: The Treatment of Traumatized Asylum Seekers, Refugees, War ... edited by Boris Drozðek, John P. Wilson

- ^ Tortured confessions: prisons and public recantations in modern Iran. p. 3

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Human Rights Watch – Defending Human Rights Worldwide". hrw.org.

- ^ Rejali, Darius. "Torture, American style". Boston.com.

- ^ "Executive Order 13491 – Ensuring Lawful Interrogations". The White House. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011.

- ^ In Yemen's secret prisons, UAE tortures and US interrogates Associated Press, 2017

- ^ de Wet, E. (2004). "The Prohibition of Torture as an International Norm of jus cogens and Its Implications for National and Customary Law". European Journal of International Law. 15 (1): 97–121. doi:10.1093/ejil/15.1.97.

- ^ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, United Nations, 10 December 1948

- ^ "What does the law say about torture?". International Committee of the Red Cross. 24 June 2011.

- ^ 18 U.S.C. § 2340 et seq..

- ^ Filártiga v. Peña-Irala, 630 F.2d 876 (2d Cir. 1980).

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Nowak, Manfred; Birk, Moritz; Monina, Giuliana (2019). The United Nations Convention Against Torture and Its Optional Protocol: A Commentary. Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-19-884617-8.

- ^ Chen, Kong-Pin; Tsai, Tsung-Sheng (2015). "Judicial Torture as a Screening Device". The B.E. Journal of Theoretical Economics. 15 (2): 277–312. doi:10.1515/bejte-2014-0023. ISSN 1935-1704. S2CID 199487672.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 22.

- ^ Thienel, Tobias (2006). "The Admissibility of Evidence Obtained by Torture under International Law". European Journal of International Law. 17 (2): 349–367. doi:10.1093/ejil/chl001. ISSN 0938-5428.

- ^ Hassner 2020, pp. 2–3.

- ^ O’Mara, Shane; Schiemann, John (2019). "Torturing science: Science, interrogational torture, and public policy". Politics and the Life Sciences. 38 (2): 180–192 [188]. doi:10.1017/pls.2019.15. PMID 32412207. S2CID 213485074.

- ^ Young & Kearns 2020, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Hassner 2020, p. 4.

- ^ Miller, Peter (2011). "Torture Approval in Comparative Perspective". Human Rights Review. 12 (4): 441–463. doi:10.1007/s12142-011-0190-2. ISSN 1874-6306. S2CID 55720374.

- ^ Mayer, Jeremy D.; Koizumi, Naoru; Malik, Ammar Anees (2014). "Does Terror Cause Torture? A Comparative Study of International Public Opinion about Governmental Use of Coercion". Examining Torture: Empirical Studies of State Repression. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 43–61. ISBN 978-1-137-43916-1.

- ^ Hajjar 2013, p. 23.

- ^ The National Archives. "Confession of Guy Fawkes." Retrieved 22 April 2007.

- ^ Davis, Barbara (1 June 2010). "'Great well of psychiatric morbidity'". insidetime.org. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Mehraby, Nooria. "Refugee Women: The Authentic Heroines". Archived from the original on 30 August 2007.

- ^ Hoffman, S. J. (2011). "Ending medical complicity in state-sponsored torture" (PDF). The Lancet. 378 (9802): 1535–1537. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60816-7. PMID 21944647. S2CID 45829194.

- ^ Heger, Heinz. The Men With the Pink Triangle. Boston: Alyson Publications, 1980.

- ^ Yamey, Gavin (11 August 2011). "Torture: European Instruments of Torture and Capital Punishment from the Middle Ages to Present". British Medical Journal. 323 (7308): 346. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7308.346.

- ^ Schreiber, Mark. The Dark Side: Infamous Japanese Crimes and Criminals. Japan: Kodansha International, 2001. Page 71

- ^ Wiehe, Vernon. Sibling Abuse: Hidden Physical, Emotional, and Sexual Trauma. New York: Lexington Books, 1990.

- ^ ""Like the Dead in Their Coffins: Torture, Detention, and the Crushing of Dissent in Iran: V. Detention Centers and Ill-Treatment". Human Rights watch. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Egypt: Collective Punishment in Scorpion Prison". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "Torture in Bahrain: UN experts decry treatment of political prisoners". IFEX. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ "In Yemen's secret prisons, UAE tortures and US interrogates". The Associated Press. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ "Authorities in Mukalla must free those being arbitrarily detained in Al Munawara Central Prison". Mwatana for Human Rights. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Evans, Malcolm D. (2020). "The Prevention of Torture". Research Handbook on Torture: Legal and Medical Perspectives on Prohibition and Prevention. Elgar. ISBN 9781788113960.

- ^ Steinerte, Elina (June 2013). "The Changing Nature of the Relationship between the United Nations Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and National Preventive Mechanisms: In Search for Equilibrium". Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights. 31 (2): 132–158. doi:10.1177/016934411303100202. S2CID 142792486.

- ^ Davenport, Christian. "Helsinki Commission Hearing". Hearing: "Is It Torture Yet?". US Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Abu Ghraib and the ISA: What's the difference? Archived 20 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Amnesty.org

- ^ Jump up to: a b c de C Williams, Amanda C; van der Merwe, Jannie (2013). "The psychological impact of torture". British Journal of Pain. 7 (2): 101–106. doi:10.1177/2049463713483596. ISSN 2049-4637. PMC 4590125. PMID 26516507.

- ^ "What is torture?". IRCT. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ Kira, Ibrahim A.; Templin, Thomas; Lewandowski, Linda; Clifford, David; Wiencek, Peggy; Hammad, Adnan; Mohanesh, Jamal; Al-haidar, Abu-Muslim (2006). "The Effects of Torture: Two Community Studies". Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. 12 (3): 205–228. doi:10.1207/s15327949pac1203_1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Rehabilitation". What is torture?. International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT). Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Deps, Patrícia D.; Aborghetti, Hugo Pesotti; Zambon, Tais Loureiro; Costa, Victória Coutinho; Dadalto dos Santos, Julienne; Collin, Simon M.; Charlier, Philippe (2020). "Assessing signs of torture: a review of clinical forensic dermatology". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.031. PMID 32946970.

- ^ Reyes, Hernán (2007). "The worst scars are in the mind: psychological torture". International Review of the Red Cross. 89 (867): 591–617. doi:10.1017/S1816383107001300. S2CID 11284625.

Sources[]

- Hajjar, Lisa (2013). Torture: A Sociology of Violence and Human Rights. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-51806-2.

- Hassner, Ron E. (2020). "What Do We Know about Interrogational Torture?". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 33 (1): 4–42. doi:10.1080/08850607.2019.1660951. S2CID 213244706.

- Rejali, Darius (2009). Torture and Democracy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3087-9.

- Young, Joseph K.; Kearns, Erin M. (2020). Tortured Logic: Why Some Americans Support the Use of Torture in Counterterrorism. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54809-0.

Further reading[]

Books[]

- Campagna, Norbert; Delia, Luigi; Garnot, Benoît (2014), La Torture, de quels droits? Une pratique de pouvoir (XVIe-XXIe siècle), Paris: Éditions Imago. ISBN 978-2-84952-710-8

- Cobain, Ian (2012). Cruel Britannia: A Secret History of Torture. London: Portobello Books. ISBN 978-1-846-27333-9.

- Conroy, John (2001). Unspeakable Acts, Ordinary People: The Dynamics of Torture. California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23039-2.

- Helbing, Franz: Die Torture. Geschichte der Folter im Kriminalverfahren aller Zeiten und Völker. Völlig neubearbeitet und ergänzt von Max Bauer, Berlin 1926 (Nachdruck Scientia-Verlag, Aalen 1973).

- Levinson, Sanford (2006). Torture: A Collection. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-530646-0.

- Maran, Rita (1989). Torture: The Role of Ideology in the French–Algerian War. New York, NY: Praeger.

- Parry, John T. (2010). Understanding Torture: Law, Violence, and Political Identity. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-05077-2.

- Peters, Edward, Torture, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996.

- Reddy, Peter (2005). Torture: What You Need to Know, Ginninderra Press, Canberra, Australia. ISBN 1-74027-322-2

- Rejali, D. M. (1994). Torture & Modernity: Self, Society, and State in Modern Iran. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Scarry, Elaine (1985). The body in pain the making and unmaking of the world. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504996-1.

- Schmid, Alex P.; Crelinsten, Ronald D. (1994). The politics of pain: torturers and their masters. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-2527-9.

- Sumanatilake, P. Saliya (2015). Why Do They Torture? A Study on Man's Cruelty. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Stamford Lake (Pvt.) Ltd. ISBN 978-955-658-406-6.

- Vreeland, James Raymond (2008). Political Institutions and Human Rights: Why Dictatorships enter into the United Nations Convention Against Torture. International Organization. pp. 62(1):65–101.

- Waldron, Jeremy; Colin Dayan (2007). The Story of Cruel and Unusual (Boston Review Books). Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-04239-0.

Articles[]

- Bromwich, David (2015). "Working the Dark Side". London Review of Books. 37 (1): 15–16.

- Danner, Mark (2015). "Our New Politics of Torture". The New York Review of Books. 62 (1).

- Wantchekon, L. & A. Healy (1999). "The 'Game' of Torture" (PDF). Journal of Conflict Resolution. 43 (5): 596–609. doi:10.1177/0022002799043005003. S2CID 51347078.

- McCoy, Alfred (2014). "How to Read the Senate Report on CIA Torture". History News Network.

External links[]

- Torture

- Abuse

- Human rights abuses

- Philosophy of law

- Ethically disputed judicial practices

- Suffering