Interrogation

Interrogation (also called questioning) is interviewing as commonly employed by law enforcement officers, military personnel, intelligence agencies, organized crime syndicates, and terrorist organizations with the goal of eliciting useful information, particularly information related to suspected crime. Interrogation may involve a diverse array of techniques, ranging from developing a rapport with the subject to torture.

Techniques[]

Deception[]

Deception can form an important part of effective interrogation. In the United States, there is no law or regulation that forbids the interrogator from lying about the strength of their case, from making misleading statements or from implying that the interviewee has already been implicated in the crime by someone else. See case law on trickery and deception (Frazier v. Cupp).[1]

As noted above, traditionally the issue of deception is considered from the perspective of the interrogator engaging in deception towards the individual being interrogated. Recently, work completed regarding effective interview methods used to gather information from individuals who score in the medium to high range on measures of psychopathology and are engaged in deception directed towards the interrogator have appeared in the literature.[2][3]

Verbal and non-verbal cues[]

The major aim of this technique is to investigate to what extent verbal and non-verbal features of liars’ and truth-tellers’ behaviour change during the course of repeated interrogations. It has shown that liars display significantly fewer smiles, self-manipulations, pauses, and less gaze aversion than truth-tellers. According to Granhag & Strömwall, there are three approaches to non-verbal deceptive behavior. The first is the emotional approach, which suggests that liars will alter their behaviors based on their own emotional feelings. For example, if a subject is lying and they begin to experience guilt, they will shift their gaze. The second approach is the cognitive approach, which suggests that lying requires more thought than telling the truth, which in turn, may result in a liar making more errors in speech. Lastly, the attempted control approach suggests a subject who is lying will attempt to be seemingly normal or honest, and will try to adjust their behaviors to make themselves believable.[4]

Good cop/bad cop[]

Good cop/bad cop is a psychological tactic used in negotiation and interrogation, in which a team of two interrogators who take apparently opposing approaches to the subject,[5] one of whom adopts a hostile or accusatory demeanor, emphasizing threats of punishment, while the other adopts a more sympathetic demeanor, emphasizing reward, in order to convince the subject to cooperate.[6]

Mind-altering drugs[]

The use of drugs in interrogation is both ineffective and illegal. The Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment (adopted by the UN General Assembly as resolution 43/173 of 9 December 1988)[7] forbids "methods of interrogation which impair the capacity of decision of judgment." Furthermore, the World Medical Association and American Medical Association, for example, both forbid participation by physicians in interrogations.[8]

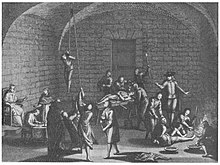

Torture[]

The neutrality of this section is disputed. (December 2015) |

The history of the state use of torture in interrogations extends over more than 2,000 years in Europe. It was recognized early on that information extracted under duress was deceptive and untrustworthy.[9] The Roman imperial jurist Ulpian in the third century AD remarked that there is "no means of obtaining the truth" from those who have the strength to resist, while those unable to withstand the pain "will tell any lie rather than suffer it."[10]

The use of torture as an investigative technique waned with the rise of Christianity since it was considered "antithetical to Christ's teachings," and in 866 Pope Nicholas I banned the practice. But after the 13th century many European states such as Germany, France, Portugal, Italy, and Spain began to return to physical abuse for religious inquisition, and for secular investigations.[10] By the 18th century the spreading influence of the Enlightenment led European nations to abandon officially state-sanctioned interrogation by torture. By 1874 Victor Hugo could plausibly claim that "torture has ceased to exist." Yet in the 20th century authoritarian states such as Mussolini's Fascist Italy, Hitler's Third Reich, and Lenin's and Stalin's Soviet Union once again resumed the practice, and on a massive scale.[11]

During the Cold War, the American Central Intelligence Agency was a significant influence among world powers regarding torture techniques in its support of anti-Communist regimes.[12] The CIA adopted methods such as waterboarding, sleep deprivation, and the use of electric shock, which were used by the Gestapo, KGB, and North Koreans from their involvement in the Korean War. The CIA also researched 'no-touch' torture, involving sensory deprivation, self-inflicted pain, and psychological stress.[13] The CIA taught its refined techniques of torture through police and military training to American-supported regimes in the Middle East, in Southeast Asia during the bloody Phoenix Program, and throughout Latin America during Operation Condor.[14] In some Asian and South Pacific nations, such as Malaysia and the Philippines, torture for interrogating and terrorizing opponents became widespread. "In its pursuit of torturers across the globe for the past forty years," writer Alfred McCoy notes, "Amnesty International has been, in a certain sense, following the trail of CIA programs."[15]

After the revelation of CIA sponsored torture in the 1970s and the subsequent outcry, the CIA largely stopped its own interrogations under torture. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, it "outsourced" such interrogation through renditions of prisoners to third world allies, often called torture-by-proxy.[16] But in the furor over the September 11 attacks, American authorities cast aside scruples,[17] legally authorizing some forms of interrogation by torture under euphemisms such as "enhanced interrogation techniques"[18] or "interrogation in depth"[19] to collect intelligence on Al Qaeda, starting in 2002.[20] Ultimately the CIA, the US military, and their contract employees tortured untold thousands at Abu Ghraib, Bagram, and secret black site prisons scattered around the globe, according to the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture and the bipartisan U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee report[21][22] Whether these interrogations under torture produced useful information is hotly disputed.[23]

The administration of President Barack Obama prohibited so-called enhanced interrogation in 2009, and as of March 2012 there is no longer a nation which openly admits to deliberate abuse of prisoners for purposes of interrogation.[24][25]

By country[]

United Kingdom[]

Statutory law and regulatory law, various legal precedents called 'case law' also impact interrogation techniques and procedures. One of the first attempts by British Courts to guide and set standards for police officers interrogating suspects was the declaration of the 'Judges' Rules' in 1912 by the judges of the King's Bench Division in England. These rules, although not law, still have weight in the United Kingdom and Canada.[26]

British military personnel were found to have misused a number of techniques during the detention of suspects in Northern Ireland in the early 1970s.[27]

United States[]

Police interrogation[]

In the United States, police interrogations are conducted under an adversarial system, in which the police seek to obtain material that will aid in convicting a suspect rather than discovering the facts of the case. To this end, a variety of tactics are employed.[28]

The Reid technique is widely used by U. S. law enforcement officers for interrogation purposes. It involves steps to obtaining a confession and methods for detecting signs of deception in the suspect's body language. The technique has been criticized for being difficult to apply across cultures and as eliciting false confessions from innocent people.[29] An example is described in the analysis of the Denver police's January 2000 interrogation of 14-year-old Lorenzo Montoya, which took place during its investigation of the murder of 29-year-old Emily Johnson.[30]

Constitutional protections[]

The Fifth Amendment, which states that one cannot be made to be "a witness against himself", prohibits law enforcement from forcing suspects to offer self-incriminating evidence.[31]

As a result of the Miranda v. Arizona ruling, police are required to read aloud to suspects under interrogation their Miranda Rights afforded to them by the Fifth Amendment, such as the right to remain silent and the right to seek counsel. If the police fail to administer the Miranda rights, all statements under interrogation are prohibited from being used as evidence in court proceedings.[32]

Push for mandatory recording of interrogations in the U.S.[]

By the 2000s, a growing movement calls for the mandatory electronic recording of all custodial interrogations in the United States.[33] "Electronic recording" describes the process of recording interrogations from start to finish. This is in contrast to a "taped" or "recorded confession," which typically only includes the final statement of the suspect. "Taped interrogation" is the traditional term for this process; however, as analog is becoming less and less common, statutes and scholars are referring to the process as "electronically recording" interviews or interrogations. Alaska,[34] Illinois,[35] Maine,[36] Minnesota,[34] and Wisconsin[37] are the only states to require taped interrogation. New Jersey's taping requirement started on January 1, 2006.[34][38] Massachusetts allows jury instructions that state that the courts prefer taped interrogations.[39] Commander Neil Nelson of the St. Paul Police Department, an expert in taped interrogation,[40] has described taped interrogation in Minnesota as the "best thing ever rammed down our throats".[41]

See also[]

- Covert interrogation

- Interrogation of Saddam Hussein

- Torture

References[]

- ^ J. D. Obenberger (October 1998). "Police Deception: The Law and the Skin Trade in the Windy City".

- ^ Perri, Frank S.; Lichtenwald, Terrance G. (2008). "The Arrogant Chameleons: Exposing Fraud Detection Homicide" (PDF). Forensic Examiner. All-about-psychology.com. pp. 26–33.

- ^ Perri, Frank S.; Lichtenwald, Terrance G. (2010). "The Last Frontier: Myths & The Female Psychopathic Killer" (PDF). Forensic Examiner. All-about-forensic-psychology.com. pp. 19:2, 50–67.

- ^ Granhag, Pär Anders; Strömwall, Lief A. (2002). "Repeated interrogations: Verbal and non-verbal cues to deception". Research Gate. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Susan Brodt & Marla Tuchinsky (March 2000). "Working Together but in Opposition: An Examination of the "Good-Cop/Bad-Cop" Negotiating Team Tactic". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 81 (2): 155–177. doi:10.1006/obhd.1999.2879. PMID 10706812.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Shonk, Katie (January 7, 2020). "The Good Cop, Bad Cop Negotiation Strategy". Harvard University. Archived from the original on March 18, 2019. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ "A/RES/43/173. Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment". www.un.org.

- ^ American Medical Association. "Physician participation in interrogation". Archived from the original on 2017-12-25.

- ^ McCoy, Alfred (2007). A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror. Henry Holt & Co. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-8050-8248-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (McCoy, a Question of Torture 2007, p. 16)

- ^ (McCoy, a Question of Torture 2007, p. 17)

- ^ (McCoy, a Question of Torture 2007, pp. 11, 59)

- ^ (McCoy, a Question of Torture 2007, p. 59)

- ^ (McCoy, a Question of Torture 2007, pp. 18, 60–107)

- ^ (McCoy, a Question of Torture 2007, p. 11)

- ^ (McCoy, a Question of Torture 2007, pp. 99, 109–10)

- ^ Froomkin, Dan (7 November 2005). "Cheney's Dark Side is Showing". Washington Post. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Transcript of interview with CIA director Panetta". NBC News. 2011-05-03. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

Enhanced interrogation has always been a kind of handy euphemism (for torture)

- ^ (McCoy, a Question of Torture 2007, p. 152)

- ^ (McCoy, a Question of Torture 2007, pp. 108, 117, 120–23, 143–44)

- ^ "Report by the Senate Armed Services Committee on Detainee Treatment". Documents.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ^ Knowlton, Brian (April 21, 2009). "Report Gives New Detail on Approval of Brutal Techniques". New York Times. (report linked to article)

- ^ Will, George (1 November 2013). "Facing up to what we did in interrogations". Washington Post. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ "Obama: U.S. will not torture – politics – White House". NBC News. 2009-01-09. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ^ Stout, David (2009-01-15). "Holder Tells Senators Waterboarding Is Torture". The New York Times.

- ^ Van Allen, Bill (2012). Criminal Investigation: In Search of the Truth. Canada: Pearson Canada. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-13-800011-0.

- ^ Mumford, Andrew (March 2012). "Minimum Force Meets Brutality: Detention, Interrogation and Torture in British Counter-Insurgency Campaigns". Journal of Military Ethics. 11 (1): 10–25. doi:10.1080/15027570.2012.674240. ISSN 1502-7570. S2CID 144565278.

- ^ Police Interrogation and American Justice. Harvard University Press. June 2009. p. 119. ISBN 9780674035317.

- ^ Kassin, Saul; Fong, Christina (1999). "'I'm Innocent!': Effects of Training on Judgments of Truth and Deception in the Interrogation room". Law and Human Behavior. 23 (5): 499–516. doi:10.1023/a:1022330011811. S2CID 53586929.

- ^ Gaines, Philip (July 1, 2018). "Presupposition as investigator certainty in a police interrogation: The case of Lorenzo Montoya's false confession". Discourse & Society. 29 (4): 399–419. doi:10.1177/0957926518754417. S2CID 148639209.

- ^ Solan, Lawrence; Tiersma, Peter Meijes (2005). Speaking of crime the language of criminal justice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Candela, Kimberlee (June 24, 2011). "Miranda Rights". In Chambliss, William J. (ed.). Courts, Law, and Justice. SAGE Publications, Inc. ISBN 9781412978576.

- ^ New Jersey Courts. Judiciary.state.nj.us. Retrieved on 2011-03-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Electronic Recording of Interrogations, Center for Policy Alternatives

- ^ "text of the new Illinois law (SB15) requiring electronic recording of custodial interrogations in murder case (The Illinois Criminal Justice Information Act)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ^ 223A: Recording of Interviews of Suspects in Serious Crimes[permanent dead link][permanent dead link]

- ^ "Wisconsin Supreme Court rules that all custodial interrogations of juveniles must be recorded. (In the Interest of Jerrell C.J.) (05-3-25)". Archived from the original on 2010-08-20. Retrieved 2010-08-20. Texas Juvenile Probation Commission.

- ^ New Rule 3:17 – Electronic Recordation. Judiciary.state.nj.us. Retrieved on 2011-03-04.

- ^ See Commonwealth v. DiGiambattista, 813 N.E.2d 516, 533–34 (Mass. 2004).

- ^ Neil Nelson & Associates Home Page Archived 2017-09-19 at the Wayback Machine. Neilnelson.com. Retrieved on 2011-03-04.

- ^ Wagner, Dennis (December 6, 2005). "FBI's policy drawing fire". The Arizona Republic. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

External links[]

| Look up interrogation in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Interrogation. |

- "The Man In The Snow White Cell". Central Intelligence Agency. April 14, 2007. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007.

- "These 11 Expert Interrogation Tips Will Improve Your Investigations!". MaestroVision.

- Interrogations

- Law enforcement