Book burning

This article has an unclear citation style. (August 2020) |

Book burning is the deliberate destruction by fire of books or other written materials, usually carried out in a public context. The burning of books represents an element of censorship and usually proceeds from a cultural, religious, or political opposition to the materials in question.[1]

In some cases, the destroyed works are irreplaceable and their burning constitutes a severe loss to cultural heritage. Examples include the burning of books and burying of scholars under China's Qin Dynasty (213–210 BCE), the obliteration of the Library of Baghdad (1258), the destruction of Aztec codices by Itzcoatl (1430s), the burning of Maya codices on the order of bishop Diego de Landa (1562), and the Burning of Jaffna Public Library in Sri Lanka (1981).

In other cases, such as the Nazi book burnings, copies of the destroyed books survive, but the instance of book burning becomes emblematic of a harsh and oppressive regime which is seeking to censor or silence some aspect of prevailing culture.

Book burning can be an act of contempt for the book's contents or author, and the act is intended to draw wider public attention to this opinion.

Art destruction is related to book burning, both because it might have similar cultural, religious, or political connotations, and because in various historical cases, books and artworks were destroyed at the same time.

In modern times, other forms of media, such as phonograph records, video tapes, and CDs have also been burned, shredded, or crushed.

When the burning is widespread and systematic, destruction of books and media can become a significant component of cultural genocide.

Historical background[]

The burning of books has a long history as a tool that has been wielded by authorities both secular and religious, in their efforts to suppress dissenting or heretical views that are believed to pose a threat to the prevailing order.

7th century BCE[]

According to the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), in the 7th century BCE King Jehoiakim of Judah burned part of a scroll that Baruch ben Neriah had written at prophet Jeremiah's dictation (Jeremiah 36).

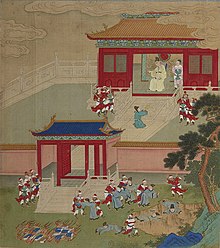

Burning of books and burying of scholars in China (210–213 BCE)[]

In 213 BCE Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty, ordered the Burning of books and burying of scholars and in 210 BCE he supposedly ordered the live burial of 460 Confucian scholars in order to stay on his throne. Though the burning of books is well established, the live burial of scholars has been disputed by modern historians who doubt the details of the story, which first appeared more than a century later in the Han Dynasty official Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian. Some of these books were written in Shang Xiang, a superior school founded in 2208 BCE. The event caused the loss of many philosophical treatises of the Hundred Schools of Thought. Treatises which advocated the official philosophy of the government ("legalism") survived.

Christian book burnings[]

In the New Testament's Acts of the Apostles, it is claimed that Paul performed an exorcism in Ephesus. After men in Ephesus failed to perform the same feat many gave up their "curious arts" and burned the books because apparently, they did not work.

And many that believed, came and confessed and shewed their deeds. Many of them also which used curious arts, brought their books together, and burned them before all men: and they counted the price of them, and found it fifty thousand pieces of silver.[2]

After the First Council of Nicea (325 CE), Roman emperor Constantine the Great issued an edict against nontrinitarian Arians which included a prescription for systematic book-burning:

"In addition, if any writing composed by Arius should be found, it should be handed over to the flames, so that not only will the wickedness of his teaching be obliterated, but nothing will be left even to remind anyone of him. And I hereby make a public order, that if someone should be discovered to have hidden a writing composed by Arius, and not to have immediately brought it forward and destroyed it by fire, his penalty shall be death. As soon as he is discovered in this offense, he shall be submitted for capital punishment....."[3]

According to Elaine Pagels, "In AD 367, Athanasius, the zealous bishop of Alexandria... issued an Easter letter in which he demanded that Egyptian monks destroy all such unacceptable writings, except for those he specifically listed as 'acceptable' even 'canonical'—a list that constitutes the present 'New Testament'".[4] (Pagels cites Athanasius's Paschal letter (letter 39) for 367 CE, which prescribes a canon, but her citation "cleanse the church from every defilement" (page 177) does not explicitly appear in the Festal letter.[5]) Heretical texts do not turn up as palimpsests, scraped clean and overwritten, as do many texts of Classical antiquity. According to author Rebecca Knuth, multitudes of early Christian texts have been as thoroughly "destroyed" as if they had been publicly burnt.[6]

Burning of Nestorian books[]

Activity by Cyril of Alexandria (c. 376–444) brought fire to almost all the writings of Nestorius (386–450) shortly after 435.[7] 'The writings of Nestorius were originally very numerous',[8] however, they were not part of the Nestorian or Oriental theological curriculum until the mid-sixth century, unlike those of his teacher Theodore of Mopsuestia, and those of Diodorus of Tarsus, even then they were not key texts, so relatively few survive intact, cf. Baum, Wilhelm and Dietmar W. Winkler. 2003. The Church of the East: A Concise History. London: Routledge.

Burning of Arian books[]

According to the Chronicle of Fredegar, Recared, King of the Visigoths (reigned 586–601) and first Catholic king of Spain, following his conversion to Catholicism in 587, ordered that all Arian books should be collected and burned; and all the books of Arian theology were reduced to ashes, along with the house in which they had been purposely collected.[9][10] Which facts demonstrate that Constantine's edict on Arian works was not rigorously observed, as Arian writings or the theology based on them survived to be burned much later in Spain.

Burning of Jewish manuscripts in 1244[]

In 1244, as an outcome of the Disputation of Paris, twenty-four carriage loads of Talmuds and other Jewish religious manuscripts were set on fire by French law officers in the streets of Paris.[11][12]

Burning of Aztec and Mayan manuscripts in the 1560s[]

During the Spanish colonization of the Americas, numerous books written by indigenous peoples were burned by the Spaniards. Several books[quantify] written by the Aztecs were burnt by Spanish conquistadors and priests during the Spanish conquest of Yucatán. Despite opposition from Catholic friar Bartolomé de las Casas, numerous books found by the Spanish in Yucatán were burnt on the order of Bishop Diego de Landa in 1562. De Landa wrote on the incident that "We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they (the Maya) regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction". The Aztec Empire had previously been in control in the region after conquering it prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, rewriting numerous books they found which concerned their lineage.[13]

Book burnings in Tudor and Stuart England[]

The founding of the Church of England after King Henry VIII broke away from the Catholic Church led to the targeting of English Catholics by Protestants. During the Tudor and Stuart periods, Protestant citizens loyal to the Crown attacked Catholic religious sites across England, frequently burning any religious texts they found. These acts were encouraged by the Crown, who pressured the general public to take part in such "spectacles". According to American historian David Cressy, over "the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries book burning developed from a rare to an occasional occurrence, relocated from an outdoor to an indoor procedure, and changed from a bureaucratic to a quasi-theatrical performance".[14]

Burning of Washington during the War of 1812[]

During the War of 1812, a British expeditionary force routed an American militia at Bladensburg. Shortly thereafter, the British marched into Washington, D.C., briefly capturing and occupying the city. In retaliation for the American destruction of Port Dover, the British ordered the destruction of several public buildings in the city, including the Library of Congress, erected just fourteen years prior. The U.S. Capitol was also burnt by the British, with books from the Library of Congress being used to burn the building. Both the library and the Capitol were rebuilt after the war.[15]

Institutions dedicated to book burnings[]

Anthony Comstock's New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, founded in 1873, inscribed book burning on its seal, as a worthy goal to be achieved. Comstock's total accomplishment in a long and influential career is estimated to have been the destruction of some 15 tons of books, 284,000 pounds of plates for printing such "objectionable" books, and nearly 4,000,000 pictures. All of this material was defined as "lewd" by Comstock's very broad definition of the term – which he and his associates successfully lobbied the United States Congress to incorporate in the Comstock Law.[16]

Nazi regime (1933)[]

The Nazi government decreed broad grounds for burning material "which acts subversively on [Nazi Germany's] future or strikes at the root of German thought, the German home and the driving forces of [German] people".[17]

Notable book burnings and destruction of libraries[]

Burnings by authors[]

In 1588, the exiled English Catholic William Cardinal Allen wrote "An Admonition to the Nobility and People of England", a work sharply attacking Queen Elizabeth I. It was to be published in Spanish-occupied England in the event of the Spanish Armada succeeding in its invasion. Upon the defeat of the Armada, Allen carefully consigned his publication to the fire, and it is only known of through one of Elizabeth's spies, who had stolen a copy.[18]

The Hassidic Rabbi Nachman of Breslov is reported to have written a book which he himself burned in 1808. To this day, his followers mourn "The Burned Book" and seek in their Rabbi's surviving writings for clues as to what the lost volume contained and why it was destroyed.[19]

Carlo Goldoni is known to have burned his first play, a tragedy called Amalasunta, when encountering unfavorable criticism.

Nikolai Gogol burned the second half of his magnum opus Dead Souls, having come under the influence of a priest who persuaded him that his work was sinful; Gogol later described this as a mistake.

As noted in Claire Tomalin's intensively researched "The Invisible Woman", Charles Dickens is known to have made a big bonfire of his letters and private papers, as well as asking friends and acquaintances to either return letters which he wrote to them or themselves destroy the letters – and most complied with his request. Dickens' purpose was to destroy evidence of his affair with the actress Nelly Ternan. To judge from surviving Dickens letters, the destroyed material – even if not intended for publication – might have had considerable literary merit.

In the 1870s Tchaikovsky destroyed the full manuscript of his first opera, The Voyevoda. Decades later, during the Soviet period, The Voyevoda was posthumously reconstructed from surviving orchestral and vocal parts and the composer's sketches.

Martin Gardner, a well-known expert on the work of Lewis Carroll, believes that Carroll had written a earlier version of Alice in Wonderland which he later destroyed after writing a more elaborate version which he presented to the child Alice who inspired the book.[20]

Alberto Santos-Dumont, after being considered a spy by the French government in 1914 and then having this deception excused by the police, he destroyed all his aeronautical documents.[21] The following year, according to the afterword to the historical novel "De gevleugelde," Arthur Japin says that when Dumont returned to Brazil, he "burned all his diaries, letters and drawings."[22]

After Hector Hugh Munro (better known by the pen name Saki) was killed in World War I in November 1916, his sister Ethel destroyed most of his papers.

Joe Shuster, who together with Jerry Siegel created the fictional superhero Superman, in 1938 burned the first Superman story when under the impression that it would not find a publisher.

In August 1963, when C.S. Lewis resigned from Magdalene College, Cambridge and his rooms there were being cleaned out, Lewis gave instructions to Douglas Gresham to destroy all his unfinished or incomplete fragments of manuscript - which scholars researching Lewis' work regard as a grievous loss.[23]

There is substantial evidence that Finnish composer Jean Sibelius worked on an Eighth Symphony. He promised the premiere of this symphony to Serge Koussevitzky in 1931 and 1932, and a London performance in 1933 under Basil Cameron was even advertised to the public. However, no such symphony was ever performed, and the only concrete evidence of the symphony's existence on paper is a 1933 bill for a fair copy of the first movement and short draft fragments first published and played in 2011.[24][25][26][27] Sibelius had always been quite self-critical; he remarked to his close friends, "If I cannot write a better symphony than my Seventh, then it shall be my last." Since no manuscript survives, sources consider it likely that Sibelius destroyed most traces of the score, probably in 1945, during which year he certainly consigned a great many papers to the flames.[28]

Aino, Sibelius' wife, recalled that "In the 1940s there was a great auto da fé at Ainola [where the Sibelius couple lived]. My husband collected a number of the manuscripts in a laundry basket and burned them on the open fire in the dining room. Parts of the Karelia Suite were destroyed – I later saw remains of the pages which had been torn out – and many other things. I did not have the strength to be present and left the room. I therefore do not know what he threw on to the fire. But after this my husband became calmer and gradually lighter in mood." It is assumed that a draft of Sibelius' Eighth Symphony - which he worked on in the early 1930s but with which he was not satisfied - was among the papers destroyed.[29]

Axel Jensen made his debut as a novelist in Oslo in 1955 with the novel Dyretemmerens kors, but he later burned the remaining unsold copies of the book.

In 1976 detractors of Venezuelan liberal writer Carlos Rangel publicly burned copies of his book From the Noble Savage to the Noble Revolutionary in the year of its publication at the Central University of Venezuela.[30][31]

Books saved from burning[]

In Catholic hagiography, Saint Vincent of Saragossa is mentioned as having been offered his life on condition that he consign Scripture to the fire; he refused and was martyred. He is often depicted holding the book which he protected with his life.

Another book-saving Catholic Saint is the 10th-century Saint Wiborada. She is credited with having predicted in 925 an invasion by the then-pagan Hungarians of her region in Switzerland. Her warning allowed the priests and religious of St. Gall and St. Magnus to hide their books and wine and escape into caves in nearby hills.[32] Wiborada herself refused to escape and was killed by the marauders, being later canonized. In art, she is commonly represented holding a book to signify the library she saved, and is considered a patron saint of libraries and librarians.

During a tour of Thuringia in 1525, Martin Luther became enraged at the widespread burning of libraries along with other buildings during the German Peasants' War, writing Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants in response.[33]

During the Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire the Imperial Court Library (now Austrian National Library) was in extreme danger, when the bombardment of Vienna caused the burning of the Hofburg, in which the Imperial Library was located. Fortunately, the fire was halted in time - saving countless irreplaceable books, diligently collected by many generations of Habsburg emperors and the scholars in their employ.

At the beginning of the Battle of Monte Cassino in World War II, two German officers – Viennese-born Lt. Col. Julius Schlegel (a Roman Catholic) and Captain Maximilian Becker (a Protestant) – had the foresight to transfer the Monte Cassino archives to the Vatican. Otherwise the archives – containing a vast number of documents relating to the 1500-years' history of the Abbey as well as some 1,400 irreplaceable manuscript codices, chiefly patristic and historical – would have been destroyed in the Allied air bombing which almost completely destroyed the Abbey shortly afterwards. Also saved by the two officers' prompt action were the collections of the Keats-Shelley Memorial House in Rome, which had been sent to the Abbey for safety in December 1942.

The Sarajevo Haggadah – one of the oldest and most valuable Jewish illustrated manuscripts, with immense historical and cultural value – was hidden from the Nazis and their Ustaše collaborators by Derviš Korkut, chief librarian of the National Museum in Sarajevo. At risk to his own life, Korkut smuggled the Haggadah out of Sarajevo and gave it for safekeeping to a Muslim cleric in Zenica, where it was hidden until the end of the war under the floorboards of either a mosque or a Muslim home. The Haggadah again survived destruction during the wars which followed the breakup of Yugoslavia.[34]

In 1940s France, a group of anti-fascist exiles created a Library of Burned Books which housed all the books that Adolf Hitler had destroyed. This library contained copies of titles that were burned by the Nazis in their campaign to cleanse German culture of Jewish and foreign influences such as pacifist and decadent literature. The Nazis themselves planned to make a "museum" of Judaism once the Final Solution was complete to house certain books that they had saved.[35]

Posthumous destruction of works[]

When Virgil died, he left instructions that his manuscript of the Aeneid was to be burnt, as it was a draft version with uncorrected faults and not a final version for release. However, this instruction was ignored. It is mainly to the Aeneid, published in this "imperfect" form, that Virgil owes his lasting fame – and it is considered one of the great masterpieces of classical literature as a whole.

Before his death, Franz Kafka wrote to his friend and literary executor Max Brod: "Dearest Max, my last request: Everything I leave behind me... in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others'), sketches, and so on, [is] to be burned unread."[36] Brod overrode Kafka's wishes, believing that Kafka had given these directions to him, specifically, because Kafka knew he would not honour them – Brod had told him as much. Had Brod carried out Kafka's instructions, virtually the whole of Kafka's work – except for a few short stories published in his lifetime – would have been lost forever. Most critics, at the time and up to the present, justify Brod's decision.[citation needed] In his forward to Kafka's The Castle Brod noted that when entering Kafka's apartment after his death, he found several big empty folders and traces of burnt paper - the manuscripts which were in these folders having evidently been destroyed by Kafka himself before his death. Brod expressed pain at the irreversible loss of this material and happiness at having saved so much of Kafka's work from its creator's ruthlessness.

A similar case concerns the noted American poet Emily Dickinson, who died in 1886 and left to her sister Lavinia the instruction of burning all her papers. Lavinia Dickinson did burn almost all of her sister's correspondences, but interpreted the will as not including the forty notebooks and loose sheets, all filled with almost 1800 poems; these Lavinia saved and began to publish the poems that year. Had Lavinia Dickinson been more strict in carrying out her sister's will, all but a small handful of Emily Dickinson's poetic work would have been lost.[37][38]

In early 1964, several months after the death of C.S. Lewis, Lewis' literary executor Walter Hooper, rescued a 64-page manuscript from a bonfire of the author's writings - the burning carried out according to Lewis' will. In 1977, Hooper published it under the name The Dark Tower. It was apparently intended as part of Lewis' Space Trilogy. Though incomplete and evidently an early draft which Lewis abandoned, its publication aroused great interest and a continued discussion among Lewis fans and scholars researching his work.

Modern biblioclasm[]

Despite the fact that the act of destroying books is condemned by the majority of the world's societies, book burning still occurs on a small or large scale. In the People's Republic of China, library officials publicize the burning of books that have fallen out of favor with the Communist Party of China's elites.[39]

In Azerbaijan, when a modified Latin alphabet was adopted, books which were published in the Arabic script were burned, especially those published in the late 1920s and 1930s.[40] The texts were not limited to the Quran; medical and historical manuscripts were also destroyed.[41]

Book burnings were regularly organised in Nazi Germany in the 1930s by stormtroopers so that "degenerate" works could be destroyed, especially works written by Jewish authors such as Thomas Mann, Marcel Proust, and Karl Marx. One of the most infamous book burnings in the 20th century occurred in Frankfurt, Germany on May 10, 1933. Organized by Joseph Goebbels, books were burned in a celebratory fashion, complete with bands, marchers, and songs. Seeking to "cleanse" German culture of the "un-German" spirit, Goebbels compelled students (who were egged on by their professors) to perform the book burning. To some this could be easily dismissed as the childish actions of the youth, but to many in Europe and America, it was a horrific display of power and disrespect.[42] During the denazification which followed the war, literature which had been confiscated by the Allies was reduced to pulp rather than burned.

In 1937, during Getúlio Vargas' dictatorship in Brazil, several books by authors such as Jorge Amado and José Lins do Rego were burned in an anti-communist act.[43]

In 1942, local Catholic priests forced Irish storyteller Timothy Buckley to burn a book The Tailor and Ansty by Eric Cross about Buckley and his wife, because of its sexual frankness.[44]

In the 1950s, over six tons of books by William Reich were burned in the U.S. in compliance with judicial orders.[45] In 1954, the works of Mordecai Kaplan were burned by Orthodox Jewish rabbis in America, after Kaplan was excommunicated.[46]

In Denmark, a comic book burning took place on 23 June 1955. It was a bonfire which consisted of comic books topped by a life-size cardboard cutout of The Phantom.[47]

During the Military dictatorship in Brazil, several methods of censure were used, among them, torture and the burning of books by firemen.[48]

Kjell Ludvik Kvavik, a senior Norwegian official, had a penchant for removing maps and other pages from rare books and he was noticed in January 1983 by a young college student. The student, Barbro Andenaes, reported the actions of the senior official to the superintendent of the reading room and then reported them to the head librarian of the university library in Oslo. Hesitant to make the accusation against Kvavik public because it would greatly harm his career, even if it was proven to be false, the media did not divulge his name until his house was searched by police. The authorities seized 470 maps and prints as well as 112 books that Kvavik had illegally obtained. While this may not have been the large scale, violent demonstration which usually occurs during wars, Kvavik's disregard for libraries and books shows that the destruction of books on any scale can affect an entire country. Here, a senior official in the Norwegian government was disgraced and the University Library was only refunded for a small portion of the costs which it had incurred from the loss and destruction of rare materials and the security changes that had to be made as a result of it. In this case, the lure of personal profit and the desire to enhance one's own collection were the causes of the defacement of rare books and maps. While the main goal was not destruction for destruction's sake, the resulting damage to the ephemera still carries weight within the library community.[49]

In 1984, Amsterdam's South African Institute was infiltrated by an organized group which was bent on drawing attention to the inequality of apartheid. Well-organized and assuring patrons of the library that no harm would come to them, group members systematically smashed microfiche machines and threw books into the nearby waterway. Indiscriminate with regard to the content which was being destroyed, shelf after shelf was cleared of its contents until the group left. Staff members fished books from the water in hopes of salvaging the rare editions of travel books, documents about the Boer Wars, and contemporary materials which were both for and against apartheid. Many of these materials were destroyed by oil, ink, and paint that the anti-apartheid demonstrators had flung around the library. The world was outraged by the loss of knowledge that these demonstrators had caused, and instead of supporting their cause and drawing people's attention to the issue of apartheid, the international community denounced their actions at Amsterdam's South African Institute. Some of the demonstrators came forward and sought to justify their actions by accusing the institute of being pro-apartheid and claiming that nothing was being done to change the status quo in South Africa.[50]

The advent of the digital age has resulted in the cataloguing of an immense collection of written works, exclusively or primarily in digital form. The intentional deletion or removal of these works has often been referred to as a new form of book burning.[51] For example, Amazon, the world's largest online marketplace, has increasingly banned the sale of controversial books. An article in the New York Times reported that "Booksellers that sell on Amazon say the retailer has no coherent philosophy about what it decides to prohibit, and seems largely guided by public complaints.".[52]

Some supporters have celebrated book-burning cases in art and other media. Such is the case with The Burning of Heretical Books over a side door on the façade of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, the bas-relief by Giovanni Battista Maini, which depicts the burning of "heretical" books as a triumph of righteousness.[53]

During the years of the Chilean military dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet (1973–1990), hundreds of books were burned as a way of repression and censorship of left-wing literature.[54][55] In some instances, even books on Cubism were burned because soldiers thought it had to do with the Cuban Revolution.[56][57]

A biblioclastic incident occurred in Mullumbimby, New South Wales, Australia in 2009. Reported as "just like the ritual burning of books in Nazi Germany", a book-burning ceremony was held by students of the "socially harmful cult" Universal Medicine, an esoteric healing business which was owned by Serge Benhayon.[58] Students were invited to throw their books onto the pyre. Most of the volumes were on Chinese medicine, kinesiology, acupuncture, homeopathy and other alternative healing modalities, all of which Benhayon has decreed evil or "prana".[59]

In 1981, the Jaffna Public Library in Jaffna, Sri Lanka, was burned down by Sinhalese police and paramilitaries during a pogrom against the minority Tamil population. At the time of its burning, it contained almost 100,000 Tamil books and rare documents.[60]

Sikh book burning[]

In the Sikh religion, any copies of their sacred book, Guru Granth Sahib, which are too badly damaged to be used, and any printer's waste which bears any of its text, are cremated. This ritual is called an Agan Bhet, and it is similar to the ritual which is performed when a deceased Sikh is cremated.[61][62][63][64]

Book burnings in popular culture[]

- In his 1821 play, Almansor, the German writer Heinrich Heine – referring to the burning of the Muslim holy book, the Qur'an, during the Spanish Inquisition – wrote, "Where they burn books, so too will they in the end burn human beings." ("Dort, wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen.") Over a century later, Heine's own books were among the thousands of volumes that were torched by the Nazis in Berlin's Opernplatz, even while his poem Die Lorelei continued to be printed in German schoolbooks as "by an unknown author".[65]

- Book burning played a small part in Journey to the Center of the Earth. After Professor Lidenbrock deciphers a writing of Arne Sakneuseum and attempts to recreate his purported subterranean journey, his nephew Axel protests this decision is poorly thought out and they should learn more about this man. Professor Lidenbrock considers it sensible, but regretfully says that is out of the question as Saknuesuem was out of favor with the leaders of his native country, who ordered all books and other works authored by him burned after his death.

- In Fahrenheit 451, about a culture which has outlawed books due to its disdain for learning, books are burned, along with the houses they are hidden in.

See also[]

- Banned books

- Library fires

- List of book-burning incidents

- Maya codices

- Bonfire of the vanities

- Bibliophobia

Further reading[]

| Library resources about Book burning |

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon. ISBN 9781134430192.

- Knuth, Rebecca (2006). Burning Books and Leveling Libraries: Extremist violence and Cultural Destruction. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

- Polastron, Lucien X. 2007. Books on Fire: The Destruction of Libraries throughout History. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions.

- The Bosnian Manuscript Ingathering Project – A call for Bosnian manuscripts ingathering

- Polastron, Lucien X. (2007) Libros en Llamas: historia de la interminable destrucción de bibliotecas. Libraria, ISBN 968-16-8398-6.[1]

- Knuth, Rebecca. Libricide : the regime-sponsored destruction of books and libraries in the twentieth century. ISBN 0-275-98088-X

- Polastron, Lucien X. Books on fire: the destruction of libraries throughout history. ISBN 978-1-59477-167-5

- Civallero, Edgardo. When Memory Turns into Ashes... Memoricide During the XX Century Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. DOI.

- UNESCO. Lost Memory – Libraries and archives destroyed in the twentieth century

- Books on Fire: The Destruction of Libraries Throughout History. Lucien Xavier Polastron. Translated by John E Graham. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1-59477-167-5. ISBN 1-59477-167-7.

- Ovenden, Richard Burning the Books. London: John Murray[66]

References[]

- ^ "Holocaust Encyclopedia: Book Burning".

- ^ Acts 19:18–20

- ^ Edict by Emperor Constantine against the Arians. Athanasius (23 January 2010). "Edict by Emperor Constantine against the Arians". Fourth Century Christianity. Wisconsin Lutheran College. Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Elaine Pagels, Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas (Random House, 2003), page 176-177

- ^ "NPNF2-04. Athanasius: Select Works and Letters". Ccel.org. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ Knuth, R. (2006). Burning books and leveling libraries, p. 13. Praeger, London. ISBN 0275990079.

- ^ "The Monks of Kublai Khan". Aina.org. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ Chapman, John. "Nestorius and Nestorianism". New Advent. The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ Duncan McMillan, Wolfgang van Emden, Philip E. Bennett, Alexander Kerr, Société Rencesvals, Guillaume d'Orange and the chanson de geste: essays presented to Duncan McMillan in celebration of his seventieth birthday by his friends and colleagues of the Société Rencesvals, University of Reading, 1984.

- ^ Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 1776–89.

- ^ Rodkinson, Michael Levi (1918). The history of the Talmud, from the time of its formation, about 200 B. C. Talmud Society. pp. 66–75.

- ^ Maccoby, Hyam (1982). Judaism on Trial: Jewish-Christian Disputations in the Middle Ages. Associated University Presses.

- ^ Murray, S. A. P. (2009). The library: An illustrated history. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

- ^ Cressy, David (2005). "Book Burning in Tudor and Stuart England". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 36 (2): 359–374. doi:10.2307/20477359. JSTOR 20477359.

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. Chicago, IL: Skyhorse Publishin. p. 158. ISBN 9781616084530.

- ^ Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957)

- ^ The Jewish Virtual Library – article The American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise [Retrieved 2015-12-19]

- ^ Catholic encyclopedia, "Spanish Armada".

- ^ "עכותור – מדריכי טיולים לעיר עכו ולכל הארץ | מדריך טיולים | מסלולי טיול לקבוצות עברית + צרפתית". Acco-tour.50webs.com. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (2000). The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04847-6.

- ^ Paul Hoffman (2003). Wings of Madness. Hyperion. p. 277. ISBN 0-7868-8571-8.

- ^ Arthur Japin (2016). O Homem com Asas (in Portuguese). Translated by Cristiano Zwiesele do Amaral. São Paulo: Planeta do Brasil. p. 285. ISBN 9788542207545.

- ^ Lindskoog, Kathryn Ann (2001). Sleuthing C.S. Lewis: more Light in the shadowlands. Mercer University Press. pp. 111–12. ISBN 0-86554-730-0.

- ^ Kilpeläinen 1995.

- ^ Sirén 2011a.

- ^ Sirén 2011b.

- ^ Stearns 2012.

- ^ "The war and the destruction of the eighth symphony 1939–1945". Jean Sibelius. Finnish Club of Helsinki.

- ^ Ross, Alex (2009) [First published 2007]. "5". The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century (3rd ed.). Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-1-84115-476-3.

- ^ "Rangel, Carlos | Fundación Empresas Polar". Biblioteca de la Fundación Polar. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ "El profesor judío, por Gustavo J. Villasmil Prieto". Tal Cual. 19 October 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ O'Donnell, Jim (20 November 2003). "Patron saints". liblicense-l@lists.yale.edu (Mailing list). Georgetown University. Retrieved 2 May 2007.

- ^ Jaroslav J. Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, Luther's Works, 55 vols. (St. Louis and Philadelphia: Concordia Pub. House and Fortress Press, 1955–1986), 46: 50–51.

- ^ Brooks, Geraldine (3 December 2007). "The Book of Exodus: A Double Rescue in Wartime Sarajevo" (PDF). The New Yorker. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books:A Living History. Los Angeles: J.Paul Getty Museum. pp. 200–201. ISBN 9781606060834.

- ^ Quoted in Publisher's Note to The Castle, Schocken Books.

- ^ Habegger, Alfred (2001). My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson. p. 604.

- ^ Farr (ed.), Judith (1996). Emily Dickinson: A Collection of Critical Essays. Prentice Hall International Paperback Editions. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-13-033524-1.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Shih, Gerry (9 December 2019). "China's library officials are burning books that diverge from Communist Party ideology". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Aziza Jafarzade, "Memoirs of 1937: Burning Our Books, The Arabic Script Goes Up in Flames," in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 14:1 (Spring 2006), pp. 24–25.

- ^ Asaf Rustamov, "The Day They Burned Our Books," in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 7:3 (Autumn 1999), pp. 74–75.

- ^ Baker, K. Burning Books. History Today. September 2006. (Pg 44)

- ^ Jorge Ramos (12 August 2012). "Ditadura Vargas incinerou em praça pública 1.640 livros de Jorge Amado" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Keating, Sara (1 January 2006). "Bringing tales of the tailor back home". The Irish Times. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Reich, Wilhelm (1897–1957), International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis

- ^ Zachary Silver, "A look back at a different book burning," The Forward, 3 June 2005

- ^ "Fantomet på bålet 1955". Danmarkshistorien.dk. 9 April 1940. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ GREENHALGH, R. D. (2020). "Os livros e a censura em Brasília durante a Ditadura Militar (1964-1985)" [Books and Censorship in Brasília during the Military Dictatorship (1964-1985)]. Informação & Sociedade: Estudos (in Portuguese). 30 (3): 1–15. doi:10.22478/ufpb.1809-4783.2020v30n3.52231. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Lawrence S. (1985). "Biblioclasm in Norway". Library & Archival Security. 6 (4): 13–16. doi:10.1300/j114v06n04_02.

- ^ Knuth, Rebecca. Burning Books and Leveling Libraries. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2006.

- ^ Ruggiero, Lucia. (n.d.). Digital books; could they make censorship and "book burning" easier? Digital Meets Culture. Retrieved 22 October 2015, from http://www.digitalmeetsculture.net/article/digital-books-could-they-make-censorship-and-book-burning-easier/ See also Deletionism and inclusionism in Wikipedia for information about this phenomenon on Wikipedia.

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/17/technology/amazon-hitler-mein-kampf.html

- ^ Noted in Touring Club Italiano, Roma e Dintorni 1965:344.

- ^ Bosmajian, Haig (2006). Burning Books. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 141. ISBN 0786422084.

- ^ "The books have been burning - World - CBC News". Cbc.ca. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ Edwards, Jorge. "Books in Chile," Index on Censorship nº 2, 1984, pp. 20–23.

- ^ Andrain, Charles. Political Change in the Third World, 2011, p. 186.

- ^ Whitbourn, Michaela (15 October 2018). "Self-styled healer Serge Benhayon leads 'socially harmful cult': jury". Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media.

- ^ Leser, David (25 August 2012). "The Da Vinci Mode". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Knuth, Rebecca. Burning Books and Leveling Libraries: Extremist Violence and Cultural Destruction. Praeger Publishers, 2006, p. 84.

- ^ "Presss Release BC Sikh Community" (PDF). Harjas.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2007.

- ^ "4 copies damaged in New Orleans by the flood caused by Hurricane Katrina". Sikhnn.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007.

- ^ "on the Nicobar Islands after the 2004 tsunami (end of page)". unitedsikhs.org.

- ^ "Blog query about an accumulation of download printouts of Sikh sacred text". Mrsikhnet.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008.

- ^ Henley, Jon (10 September 2010). "Book-burning: fanning the flames of hatred". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ^ Burning the Books by Richard Ovenden review – the libraries we have lost; The Guardian; 31 August 2020; accessed 2020-09-02

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Book burning |

- "On Book Burnings and Book Burners: Reflections on the Power (and Powerlessness) of Ideas" by Hans J. Hillerbrand

- "Burning books" by Haig A. Bosmajian

- "Bannings and burnings in history" – Book and Periodical Council (Canada)

- "The books have been burning: timeline" by Daniel Schwartz, CBC News. Updated 10 September 2010

- Book burnings

- Events relating to freedom of expression

- Book censorship

- History of books

- Historical negationism

- Freedom of expression

- Protest tactics

- Anti-intellectualism