Brandeis Brief

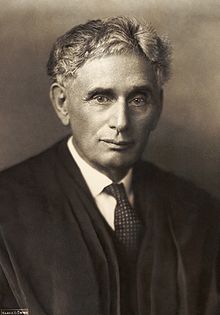

The Brandeis brief was a pioneering legal brief that was the first in United States legal history to rely more on a compilation of scientific information and social science than on legal citations.[1] It is named after then-litigator and eventual associate Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who presented it in his argument for the 1908 US Supreme Court case Muller v. Oregon. The brief was submitted in support of a state law restricting the number of hours women were allowed to work.[2] The Brandeis brief consisted of more than 100 pages, only two of which were devoted to legal argument.[3] The rest of the document contained testimony by medics, social scientists, and male workers arguing that long working hours had a negative effect on the "health, safety, morals, and general welfare of women."[4][5]

Brandeis's sister-in-law, legal reformer Josephine Clara Goldmark of the National Consumers League, helped compile most of the information in the brief.[6] In describing these women's research efforts, Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote the following:

"Josephine Goldmark, aided by her sister Pauline and several volunteer researchers, scoured the Columbia University and New York Public Libraries in search of materials of the kind Brandeis wanted—facts and figures on dangers to women’s health, safety, and morals from working excessive hours, and on the societal benefits shortened hours could yield. Data was extracted from reports of factory inspectors, physicians, trade unions, economists, and social workers. Within a month, Goldmark’s team compiled information that filled 98 of the 113 pages in Brandeis’ brief."[7]

The Brandeis brief had shortcomings and its audacity is sometimes overstated. Oregon's attorney general filed a traditional companion brief that cited the needed legal precedents.[8] Some of the scientific evidence detailed in the Brandeis brief was later challenged and refuted.[8] But it still is regarded as a pioneering attempt to combine law and social science.[9] The Brandeis brief changed the direction of the Supreme Court and of U.S. law. It is considered a model for future Supreme Court presentations in cases affecting the health or welfare of classes of individuals. This strategy of combining legal argument with scientific evidence was later successfully used in Brown v. Board of Education to demonstrate the harmful psychological effects of segregated education on African-American children.[10][11]

References[]

- ^ Strum, Philippa (1989). "Brandeis and the Living Constitution". In Dawson, Nelson L. (ed.). Brandeis and America. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-8131-1690-7.

- ^ Schwartz, Bernard (1993). A history of the Supreme Court. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-19-508099-5.

- ^ Rosen, Paul L. (1972). The Supreme Court and social science. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-252-00235-9.

- ^ Johnson, John W. (1992). "Brandeis Brief". In Hall, Kermit (ed.). The Oxford companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-0-19-505835-2.

- ^ Baer, Judith A. (1978). The chains of protection: the judicial response to women's labor legislation. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8371-9785-2.

- ^ Jewish Women's Archive, "Josephine Clara Goldmark."

- ^ Ginsburg, Ruth Bader. "Lessons Learned from Louis D. Brandeis | BrandeisNOW." BrandeisNOW. N.p., 28 Jan. 2016. Web. 28 Sept. 2016.

- ^ a b Bernstein, David E. (Autumn 2011). "Brandeis Brief Myths" (PDF). The Green Bag. 15 (1): 9–15.

- ^ Yovel, Jonathan; Mertz, Elizabeth (2004). "The Role of Social Science in Legal Decisions". In Sarat, Austin (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Law and Society. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishing. p. 414. ISBN 978-1-78034-114-9.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2009). "NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund". Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-First Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-19-516779-5.

- ^ Cawthorne, Elisabeth A. (2004). Medicine on Trial: A Handbook With Cases, Laws, and Documents. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-85109-564-3.

Further reading[]

- Bernstein, David E. (2011). "Brandeis Brief Myths" (PDF). The Green Bag. 15 (1): 9–15.

- Evans, Sandra S.; Scott, Joseph E. (1983). "Social Scientists as Expert Witnesses: Their Use, Misuse, and Sometimes Abuse". Law & Policy Quarterly. 5 (2): 181–214. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9930.1983.tb00295.x. ISSN 0164-0267.

- Garfinkel, Herbert (1959). "Social Science Evidence and the School Segregation Cases". Journal of Politics. Cambridge University Press. 21 (1): 37–59. doi:10.2307/2126643. JSTOR 2126643.

- Tomkins, Alan J.; Oursland, Kevin (1991). "Social and social scientific perspectives in judicial interpretations of the constitution: A historical view and an overview". Law and Human Behavior. 15 (2): 101–120. doi:10.1007/BF01044613.

External links[]

- The full Brandeis brief, courtesy of the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law (University of Louisville)

- 1908 in law

- 1908 in the United States

- Works by Louis Brandeis

- United States law stubs