Breathless (1960 film)

| Breathless | |

|---|---|

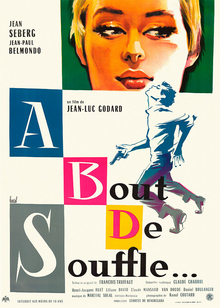

Theatrical release poster | |

| French | À bout de souffle |

| Directed by | Jean-Luc Godard |

| Screenplay by | Jean-Luc Godard |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | Georges de Beauregard |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Raoul Coutard |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Martial Solal |

Production company | Les Films Impéria |

| Distributed by | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | FRF 400,000[1] (US$80,000)[2] |

| Box office | 2,082,760 admissions (France)[3] |

Breathless (French: À bout de souffle, lit. 'Out of Breath') is a 1960 French crime drama film written and directed by Jean-Luc Godard. It stars Jean-Paul Belmondo as a wandering criminal named Michel, and Jean Seberg as his American girlfriend Patricia. The film was Godard's first feature-length work and represented Belmondo's breakthrough as an actor.

Breathless is one of the earliest and more influential examples of French New Wave (nouvelle vague) cinema.[4] Along with François Truffaut's The 400 Blows and Alain Resnais's Hiroshima mon amour, both released a year earlier, it brought international attention to new styles of French filmmaking. At the time, Breathless attracted much attention for its bold visual style, which included unconventional use of jump cuts.

Upon its initial release in France, the film attracted over two million viewers. It has since become considered one of the best films ever made, appearing in Sight & Sound magazine's decennial polls of filmmakers and critics on the subject on multiple occasions. In May 2010, a fully restored version of the film was released in the United States to coincide with the film's 50th anniversary.

Plot[]

Michel is a youthful, dangerous criminal who models himself on the film persona of Humphrey Bogart. After stealing a car in Marseille, Michel shoots and kills a policeman who has followed him onto a country road. Penniless and on the run from the police, he turns to an American love interest, Patricia, a student and aspiring journalist, who sells the New York Herald Tribune on the boulevards of Paris. The ambivalent Patricia unwittingly hides him in her apartment as he simultaneously tries to seduce her and call in a loan to fund their escape to Italy. Patricia says she is pregnant, probably with Michel's child. She learns that Michel is on the run when questioned by the police. Eventually she betrays him, but before the police arrive, she tells Michel what she has done. He is somewhat resigned to a life in prison, and does not try to escape at first. The police shoot him in the street, and after running along the block, he dies "à bout de souffle" ("out of breath").

Closing dialogue[]

The film's final lines of dialogue cause some confusion for English-speaking audiences. The original French is ambiguous; it is unclear whether Michel is condemning Patricia or condemning the world in general, and it is unclear whether Patricia is questioning his scorn, questioning the meaning of a French word as elsewhere in the film, or unable to understand the concept of shame.[citation needed]

As Patricia and Detective Vital catch up with the dying Michel, they have the following dialogue:

This translates as:

MICHEL: It's really disgusting.

PATRICIA: What did he say?

VITAL: He said you are really disgusting.

PATRICIA: What is "disgusting"?

In French, "dégueulasse" also has the connotation of "nauseating", or making one want to throw up; in reference to a person, it can be loosely translated as a "disgusting person", i.e. a "louse", "scumbag", or "bitch".

In the English captioning of the 2001 Fox-Lorber Region One DVD, "dégueulasse" is translated as "scumbag", producing the following dialogue:

MICHEL: It's disgusting, really.

PATRICIA: What did he say?

VITAL: He said "You're a real scumbag".

PATRICIA: What's a scumbag?

The 2007 Criterion Collection Region One DVD uses a less literal translation:

MICHEL: Makes me want to puke.

PATRICIA: What did he say?

VITAL: He said you make him want to puke.

PATRICIA: What's that mean, "puke"?

This translation was used in the 2010 restoration.

Cast[]

- Jean-Paul Belmondo as Michel Poiccard

- Jean Seberg as Patricia Franchini

- Daniel Boulanger as Police Inspector Vital

- as Antonio Berruti

- Roger Hanin as Carl Zumbach

- as Van Doude

- as Lilane

- as the other inspector

- Jean-Pierre Melville as Parvulesco

- as the used car salesman

- Jean-Luc Godard as an informer

- as Tolmachoff

- Philippe de Broca as an extra

- as an extra

- Jean Douchet as an extra

- Jean Herman as an extra

- Andre S. Labarthe as an extra[7]

- Jacques Rivette as the body of the man hit by a car

Themes[]

American philosopher Hubert Dreyfus saw the film as exemplifying Friedrich Nietzsche's conception of ("active" versus "passive") nihilism. On this reading, Michel and Patricia are attracted to each other because both live life as essentially meaningless. As an active nihilist, Michel responds to this condition with "cheerfulness, intensity, and style" (modelled on Bogart, whose humorous gestures he adopts), throwing himself fully into momentary engagements, including reckless crime and his love for Patricia. Patricia, as a passive nihilist, however, rejects all engagements, dissatisfied with and afraid of the very meaninglessness that Michel enjoys. In the end, she turns him in to the police so that he will be forced to leave and the love affair will end; but he instead throws himself into death with undiminished gusto. Her puzzled reaction to his final performance leaves its impact on her attitude open.[8]

Production[]

Background and writing[]

Breathless was based loosely on a newspaper article that François Truffaut read in The News in Brief. The character of Michel Poiccard is based on real-life Michel Portail and his American girlfriend and journalist Beverly Lynette. In November 1952, Portail stole a car to visit his sick mother in Le Havre and ended up killing a motorcycle cop named Grimberg.[9]

Truffaut worked on a treatment for the story with Claude Chabrol, but they dropped the idea when they could not agree on the story structure. Godard had read and liked the treatment and wanted to make the film. While working as a press agent at 20th Century Fox, Godard met producer Georges de Beauregard and told him that his latest film was not any good. De Beauregard hired Godard to work on the script for Pêcheur d'Islande. After six weeks, Godard became bored with the script and instead suggested making Breathless. Chabrol and Truffaut agreed to give Godard their treatment and wrote de Beauregard a letter from the Cannes Film Festival in May 1959 agreeing to work on the film if Godard directed it. Truffaut and Chabrol had recently became star directors, and their names secured financing for the film. Truffaut was credited as the original writer and Chabrol as the technical adviser. Chabrol later claimed that he only visited the set twice and Truffaut's biggest contribution was persuading Godard to cast Liliane David in a minor role.[9] Fellow New Wave director Jacques Rivette appears in a cameo as the dead body of a man hit by a car in the street.[10]

Godard wrote the script as he went along. He told Truffaut "Roughly speaking, the subject will be the story of a boy who thinks of death and of a girl who doesn't."[11] As well as the real-life Michel Portail, Godard based the main character on screenwriter Paul Gégauff, who was known as a swaggering seducer of women. Godard also named several characters after people he had known earlier in his life when he lived in Geneva.[9] The film includes a couple of in-jokes as well: the young woman selling Cahiers du Cinéma on the street (Godard had written for the magazine), and Michel's occasional alias of Laszlo Kovacs, the name of Belmondo's character in Chabrol's 1959 film Web of Passion.

Truffaut believed Godard's change to the ending was a personal one. "In my script, the film ends with the boy walking along the street as more and more people turn and stare after him, because his photo's on the front of all the newspapers.[12]...Jean-Luc chose a violent end because he was by nature sadder than I.... he had need of [his] particular ending. At the end, when the police are shooting at him one of them said to his companion, 'Quick, in the spine!' I told him, 'You can't leave that in.'"[11]

Jean-Paul Belmondo had appeared in a few feature films before Breathless, but he had no name recognition outside France at the time Godard was planning the film. In order to broaden the film's commercial appeal, Godard sought a prominent leading lady who would be willing to work in his low-budget film. He came to Jean Seberg through her then-husband Francois Moreuil, with whom he had been acquainted.[13] Seberg agreed to appear in the film on 8 June 1959 for $15,000, which was one-sixth of the film's budget. Godard ended up giving Seberg's husband a small part in the film.[9] During the production, Seberg privately questioned Godard's style and wondered if the film would be commercially viable. After the film's success, she collaborated with Godard again on the short Le Grand Escroc, which revived her Breathless character.[13]

Godard initially wanted cinematographer to shoot the film after having worked with him on his first short films. De Beauregard instead hired Raoul Coutard, who was under contract to him.[14]

The 1958 ethno-fiction Moi, un noir has been credited as a key influence for Godard. This can be seen in the adoption of jump-cuts, use of real locations rather than constructed sets and the documentary, newsreel format of filming.[15][16]

Filming[]

Godard envisaged Breathless as a reportage (documentary), and tasked cinematographer Raoul Coutard to shoot the entire film on a hand-held camera, with next to no lighting.[17] In order to shoot under low-light levels, Coutard had to use Ilford HP5 film, which was not available as motion picture film stock at the time. He therefore took 18-metre lengths of HP5 film sold for 35mm still cameras and spliced them together to 120-metre rolls. During development he pushed the negative one stop from 400 ASA to 800 ASA.[18] The size of the sprocket holes in the photographic film was different from that of motion picture film, and the Cameflex camera was the only camera that worked for the film used.[19]

The production was filmed on location in Paris using an Eclair Cameflex during the months of August and September in 1959,[17] including U.S. President Eisenhower's 2–3 September visit to Paris.[20] Nearly the entire film had to be dubbed in post-production because of the noisiness of the Cameflex camera[21] and because the Cameflex was incapable of synchronized sound.[14]

Filming began on 17 August 1959. Godard met his crew at the Café Notre Dame near the Hôtel de Suède and shot for two hours until he ran out of ideas.[9] Coutard has stated that the film was virtually improvised on the spot, and that Godard wrote lines of dialogue in an exercise book that no one else was allowed to see.[9] Godard gave the lines to Belmondo and Seberg with only a few brief rehearsals of scenes before filming them. No permission was received to shoot the film in its various locations (mainly the side streets and boulevards of Paris), adding to the spontaneous feel for which Godard was aiming.[22] However, all locations were selected before shooting began, and assistant director Pierre Rissient has described the shoot as very organized. Actor Richard Balducci has stated that shooting days ranged from 15 minutes to 12 hours, depending on how many ideas Godard had on a given day. Producer Georges de Beauregard wrote a letter to the entire crew complaining about the erratic shooting schedule. Coutard said that when de Beauregard encountered Godard at a café on a day on which Godard had called in sick, the two engaged in a fistfight.[14]

Godard shot most of the film chronologically, with the exception of the first sequence, which was filmed toward the end of the shoot.[9] Filming at the Hôtel de Suède for the lengthy bedroom scene with Michel and Patricia included a minimal crew and no lights. The location was difficult to secure, but Godard was determined to shoot there after having lived at the hotel after returning from South America in the early 1950s. Instead of renting a dolly with complicated and time-consuming tracks to lay, Godard and Coutard rented a wheelchair that Godard often pushed himself.[14] For certain street scenes, Coutard hid in a postal cart with a hole for the lens and packages piled on top of him.[9] Shooting lasted for 23 days and ended on 12 September 1959. The final scene in which Michel is shot in the street was filmed on the rue Campagne-Première in Paris.[9]

Writing for Combat magazine in 1960, observed: "It seems that, if we had footage of Godard shooting his film, we would discover a sort of accord between the dramatized world in front of the camera (Belmondo and Seberg playing a scene) and the working world behind it (Godard and Raoul Coutard shooting the scene), as if the wall between the real and projected worlds had been torn down."[citation needed]

Editing[]

Breathless was processed and edited at GTC Labs in Joinville by lead editor Cécile Decugis and assistant editor Lila Herman. Decugis has said that the film had a bad reputation before its premiere as the worst film of the year.[9]

Coutard said that "there was a panache in the way it was edited that didn't match at all the way it was shot. The editing gave it a very different tone than the films we were used to seeing."[14] The film's use of jump cuts has been called innovative. Andrew Sarris analyzed it as existentially representing "the meaninglessness of the time interval between moral decisions."[23] Assistant director Pierre Rissient said that the jump cut style was not intended during the film's shooting or the initial stages of editing.[14]

Reception[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (September 2020) |

In his 2008 biography of Godard, Richard Brody wrote: "The seminal importance of the film was recognized immediately. In January 1960 – prior to the film's release – Godard won the Jean Vigo Prize, awarded 'to encourage an auteur of the future' ... Breathless opened in Paris ... not in an art house but at a chain of four commercial theaters, selling 259,046 tickets in four weeks. The eventual profit was substantial, rumored to be fifty times the investment. The film's success with the public corresponded to its generally ardent and astonished critical reception ... Breathless, as a result of its extraordinary and calculated congruence with the moment, and of the fusion of its attributes with the story of its production and with the public persona of its director, was singularly identified with the media responses it generated."[24]

The New York Times critic A. O. Scott wrote in 2010, 50 years after the release of Breathless, that it is both "a pop artifact and a daring work of art" and even at 50, "still cool, still new, still – after all this time! – a bulletin from the future of movies."[25] Roger Ebert included it on his "Great Movies" list in 2003, writing that "No debut film since Citizen Kane in 1942 has been as influential," dismissing its jump cuts as the biggest breakthrough, and instead calling revolutionary its "headlong pacing, its cool detachment, its dismissal of authority, and the way its narcissistic young heroes are obsessed with themselves and oblivious to the larger society."[26]

As of 6 December 2019, the film holds a 97% approval rating on review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 64 reviews, with an average rating of 8.71/10. The site's critical consensus says, "Breathless rewrote the rules of cinema – and more than 50 years after its arrival, Jean-Luc Godard's paradigm shifting classic remains every bit as vital."[27]

Awards[]

Legacy[]

Godard said the success of Breathless was a mistake. He added "there used to be just one way. There was one way you could do things. There were people who protected it like a copyright, a secret cult only for the initiated. That's why I don't regret making Breathless and blowing that all apart."[29] In 1964, Godard described his and his colleagues' impact: "We barged into the cinema like cavemen into the Versailles of Louis XV."[30]

Breathless ranked as the No. 22 best film of all time in the decennial British Film Institute's 1992 Sight and Sound Critics' Poll. In the 2002 poll, it ranked 15th.[31] Ten years later, in 2012, Breathless was the No. 13 best film of all time in the overall Sight and Sound poll,[32] and the 11th best film in the concurrent Directors' Poll.[33] In 2018 the film ranked 11th on the BBC's list of the 100 greatest foreign-language films, as voted on by 209 film critics from 43 countries.[34]

References to other films[]

- Forty Guns, directed by Sam Fuller, had a POV shot through a barrel of a gun that cuts to a couple kissing.[35]

- Pushover, directed by Richard Quine[35]

- Where the Sidewalk Ends, directed by Otto Preminger[35]

- Whirlpool, directed by Otto Preminger, is the film playing when Patricia attempts to lose the police officer that is following her.[35]

- Bonjour tristesse, directed by Otto Preminger. Godard said that Patricia was a continuation of Seberg's character Cécile.[35]

- The Maltese Falcon, directed by John Huston. Michel paraphrases a line of dialogue from the film about always falling in love with the wrong women.[35]

- The Glass Key, a novel by Dashiell Hammett. A character criticizing Michel for wearing silk socks with a tweed jacket is a reference to the Hammett novel.[35]

- Bob le flambeur, directed by Jean-Pierre Melville. Michel makes reference to the lead character Bob Montagné being in jail.[35]

- The Harder They Fall, directed by Mark Robson, the lobby card of Humphrey Bogart that Michel imitates is from this film.[35]

- The film is dedicated to Monogram Pictures, which Jonathan Rosenbaum called "a critical statement of aims and boundaries."[35]

In popular culture[]

This section does not cite any sources. (July 2013) |

- The film is frequently referenced in the Youth in Revolt book series, being a favorite of female protagonist Sheeni Saunders, including her dreams of running off to France and her fascination for Jean-Paul Belmondo.

- In The Doom Generation, characters play the "smile or I'll choke you" game, and the film's semi-general theme is of a "nihilistic road movie".

- The Australian band The Death Set named their album from 2011 after main character Michel Poiccard.[36]

- The final scene is mentioned (and later alluded to visually) in The Squid and the Whale.[37]

- In the third episode of Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex, "Android and I", a 35mm reel of this film can be seen on a table, beneath a reel of Alphaville, as Togusa and Batou are investigating the house of a suspect. Other Godard works are also scattered through the scene. Dialog from this film is recited by two other characters throughout the episode. Themes from this episode parallel themes from both this movie and Godard's complete oeuvre. The climax of the episode hinges on the final lines, including one additional line, from the final scene of the film.

- In an episode of Brooklyn Nine-Nine, Sergeant Jeffords mentions Breathless when the detectives are discussing their favorite cop movies. Jeffords identifies the film as "François Truffaut's Breathless", despite the fact that only the director's name is generally used in such a way. In reference to this error, Jeffords is seen later in the season at a party, defending his statement by saying "it's a writer's film".

- In The Dreamers one of the protagonists re-enacts a scene from the film.

- The final scene is recreated in Romeo Void's "Never Say Never" video.

- In issue #30 of IDW's ongoing comic book series Transformers: More Than Meets the Eye, Whirl votes for repeat showings of the film during the crew's movie night.

- The Canadian band The Tragically Hip made a music video for the song "In View" that pays homage to the film.

- In the 2001 Novel The Incorrigible Optimists Club by Jean-Michel Guenassia, the main character sees the film in the cinema with his family. The theater is empty and the woman working the ticket stand advises against seeing it. Nonetheless, he loves the film.

- The 2017 Malayalam-language film Mayaanadhi (Mystic River), directed by Ashiq Abu, draws inspiration from Breathless.[38]

- The 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde contains numerous visual references to Breathless, including an early shot of Warren Beatty wearing a fedora slanted over his eyes and with a match tilted upward held in his lips, echoing Jean-Paul Belmondo's hat and cigarette in the opening scenes of Breathless. Later Beatty also wears a pair of round-rim black sunglasses with one lens missing, an exact visual reference to Belmondo wearing the same sunglasses with a missing lens later in Breathless. Bonnie and Clyde also shares a general storyline with Breathless, involving a handsome, nihilistic young killer who steals cars and who connects with a beautiful, free-spirited young woman. Pauline Kael, in her 1967 review of Bonnie and Clyde in The New Yorker, wrote that "If this way of holding more than one attitude toward life is already familiar to us—if we recognize the make-believe robbers whose toy guns produce real blood, and the Keystone cops who shoot them dead, from Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player and Godard’s gangster pictures, Breathless and Band of Outsiders—it’s because the young French directors discovered the poetry of crime in American life (from our movies) and showed the Americans how to put it on the screen in a new, 'existential' way."

- Daryush Shokof makes the all-female film Breathful with reference to Breathless.

- In A Very Secret Service, the characters go to see Breathless in a movie theater, and are shown watching the iconic final scene.

See also[]

- Breathless, a 1983 American remake starring Richard Gere in the Belmondo role and Valérie Kaprisky in the Seberg role

- List of French-language films

- List of films considered the best

References[]

- ^ Marie, Michel (2009). La nouvelle vague: Une école artistique. Armand Colin. ISBN 9782200247027.

- ^ Marie, Michel (2008). The French New Wave: An Artistic School. Translated by Neupert, Richard. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470776957.

- ^ Box office information for film at Box Office Story

- ^ Film: Video and DVD Guide 2007. London: Halliwell's. 2007. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-00-723470-7.

- ^ Dudley Andrew (1987). Breathless, chapter: Continuity script for the film. Rutgers Films in Print series. Rutgers University Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-8135-1253-2.

- ^ "Breathless (1960) - FAQ". IMDb. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ The Criterion Collection. Breathless DVD. Additional book. 2007. pp. 6.

- ^ "Professor Dreyfus lecture - Breathless (À bout de souffle) Active & Passive Nihilism". YouTube. 17 June 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Ventura, Claude; Villetard, Xavier (2016). (DVD) (in French). The Criterion Collection. OCLC 960384313. 1993 French television documentary (78 minutes). The documentary (with English subtitles) is included as a special feature of the Criterion Collection DVD releases of Breathless.

- ^ Brody, Richard (2008). Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard. New York, New York: Metropolitan Books. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8050-8015-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fotiade, Ramona (28 May 2013). A Bout de Souffle: French Film Guide. I.B.Tauris. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0-85772-117-4. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ "Francois Truffaut on 'Breathless'" (PDF). Breathless 50th Anniversary Restoration. Rialto Pictures Pressbook. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Jean Seberg Enigma: Interview with Garry McGee" Archived 25 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Film Threat, 28 March. 2008

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Criterion. Coutard and Rissient.

- ^ CinemaTyler (3 February 2015), What I Learned From Watching: Breathless (1960) [INTERACTIVE VIDEO], retrieved 2 July 2019

- ^ "CIP-IDF > Projections du 4 juin". www.cip-idf.org. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Begery, Benjamin. Reflections: Twenty-one cinematographers at work, p. 200. ASC Press, Hollywood.

- ^ Salt, Barry (2009). Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis (3 ed.). Starword. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-9509066-5-2.

- ^ The Criterion Collection. Breathless DVD. Special Features, disc 2. Coutard and Rissient. 2007.

- ^ Dott, Robert C. (4 September 1959). "Eisenhower Gets Accord in France". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Begery, Benjamin. Reflections: Twenty-one cinematographers at work, p. 201. ASC Press, Hollywood.

- ^ Solomons, Jason (6 June 2010). "Jean-Luc Godard would just turn up scribble some dialogue, and we would rehearse maybe a few times". The Observer.

- ^ The Criterion Collection. Breathless DVD. Special Features, disc 2. Breathless as Criticism. 2007.

- ^ Brody, Richard (2008). Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard. Henry Holt & Co. p. 72.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (21 May 2010). "A Fresh Look Back at Right Now". The New York Times. p. AR10. Retrieved 29 May 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (20 July 2003). "Breathless". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ "Breathless (1961)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ "Berlinale: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ^ The Criterion Collection. Breathless DVD. Special Features, disc 1. Interviews. 2007.

- ^ Brody, Richard, Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard, Henry Holy & Co., 2008, p. 72

- ^ "Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002". Archived from the original on 15 May 2012.

- ^ "Sight & Sound Poll 2012: Top 10 Films of All Time". Awards Daily. August 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Directors' top 100". bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on 24 August 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Foreign Language Films". British Broadcasting Corporation. 29 October 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Criterion. Breathless as Criticism.

- ^ "The Death Set: Michel Poiccard". Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ "Breathless reference in The Squid and the Whale". Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ "Is Mayaanadhi a copy of Godard's French classic Breathless?". January 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

External links[]

- Breathless at IMDb

- Breathless at AllMovie

- Breathless at Rotten Tomatoes

- Why Breathless (Essay on ThoughtCatalog.com)

- Breathless on NewWaveFilm.com

- Breathless Then and Now an essay by Dudley Andrew at the Criterion Collection

- 1960 films

- 1960 crime drama films

- 1960 directorial debut films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Jean-Luc Godard

- Films set in Paris

- French black-and-white films

- French crime drama films

- French films

- French-language films