My Life to Live

| My Life to Live | |

|---|---|

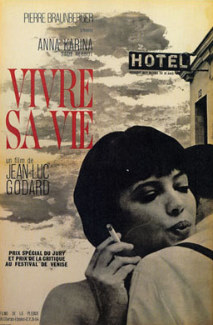

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jean-Luc Godard |

| Written by | Jean-Luc Godard |

| Produced by | Pierre Braunberger |

| Starring | Anna Karina Sady Rebbot André S. Labarthe |

| Cinematography | Raoul Coutard |

| Edited by | Jean-Luc Godard |

| Music by | Michel Legrand |

| Distributed by | Panthéon Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 85 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Budget | $40,000[1] |

My Life to Live (French: Vivre sa vie : film en douze tableaux; To Live Her Life: A Film in Twelve Scenes) is a 1962 French New Wave drama film directed by Jean-Luc Godard. In the United Kingdom, the film was released under the title It's My Life.

Plot[]

The film is told through 12 "episodes", each preceded by a written intertitle. Nana Kleinfrankenheim (Anna Karina) is a beautiful Parisian in her early twenties. She leaves her husband Paul and her infant son, hoping to become an actress. The couple meet in a café and play pinball one last time before deciding to end their marriage. She works in a record store, helping customers find music based on their tastes. After leaving her husband, she is not able to make much money on her own and is worried she will not be able to afford rent. She asks several coworkers if they can spare her 2,000 francs but all refuse.

Nana tries to enter her apartment but the landlady refuses to let her in until she can pay rent. The next day, Nana meets Paul who gives her pictures of her son to keep for herself. Paul invites her to eat but Nana declines and explains she is seeing a film with another man. They watch The Passion of Joan of Arc, moving Nana to tears. After the film, Nana ditches her date to meet with a man who promised he would take photos of her for career exposure as an actress. He says she will have to undress for the photos and Nana reluctantly complies.

Nana is questioned in a police station for trying to steal 1,000 francs from a woman on the street, who dropped the money in front of her. Nana returned the money out of guilt, but the woman still presses charges. Nana says she doesn't know what to do or who she will live with now. Nana walks down a street noticing a woman prostituting herself. A man asks Nana if he can join her, assuming she is also a prostitute, she says yes and they enter a hotel. Inside the room Nana asks him for 4,000 francs. He gives 5,000 and says she can keep the change. They kiss but Nana is visibly uncomfortable and struggling to avoid his lips.

Nana runs into a friend, Yvette, and they go for lunch. Yvette talks about how her husband abandoned her and her children, and that over time she became a prostitute because it was the easiest way to make money without him. Yvette's pimp, Raoul, is at the diner and Yvette tells him he should speak to Nana. Nana makes a good impression on Raoul and the three play pinball when suddenly a police shootout occurs outside and a man who has been shot runs inside. After seeing the blood-covered man Nana flees the diner without saying anything.

Some time later, Nana has returned to the restaurant and is writing a letter asking for work (presumably as a prostitute) to an address Yvette gave her, describing herself and her physical features. Raoul sits down next to her and they talk about the shootout from a few days earlier. He tells Nana he thinks it would be better for her to stay and work in Paris instead of where she was planning to go, as she will make more money here. Nana agrees to work for him and they kiss. She quits her job at the record store and begins to let go of her dream of becoming an actress. Raoul explains the basics of being a prostitute to Nana: what she does, how to conduct herself, how much she charges and earns, when and where she works, the laws, what to do if she gets pregnant. The dialogue between Nana and Raoul plays over scenes of Nana prostituting herself to many different men, it seems she has now been doing it for some period of time.

On one of Nana's days off Raoul takes her to a bistro to meet some of his friends. There, Nana turns a pop song on the jukebox and dances around the room. The men are mostly uninterested. Later, Nana is on the street and picks up a client whom she takes to a hotel. The man requests she ask other prostitutes in the hotel to join them, but once one does, the client says he doesn't want Nana to join, so she sits on the edge of the bed and smokes while she waits.

Nana is now a seasoned prostitute and blends in with the others on the streets. She enters a café where she has a philosophical discussion with an old man sitting in the booth next to hers. They converse about communication, language and love. Nana reflects on her own identity. Nana is in a hotel room with a young man who reads aloud a passage from "The Oval Portrait" by Edgar Allan Poe. Nana and the young man express their adoration of each other and Nana decides she will live with him, planning to tell Raoul she is quitting being a prostitute. When Nana confronts Raoul they argue, as he was planning to sell her to another pimp. Raoul forces Nana to get in his car and drives her to the pimp's meeting place. However, the transaction goes bad and Nana ends up being killed in a gun battle. The pimps flee the scene, leaving Nana's body lying on the pavement.

Cast[]

- Anna Karina as Nana Kleinfrankenheim

- Sady Rebbot as Raoul (as Saddy Rebbot)

- André S. Labarthe as Paul

- as Yvette (as G. Schlumberger)

- as Le chef

- as Elisabeth

- as Journaliste

- as Dimitri

- Peter Kassovitz as Le jeune homme

- as Luigi (as E. Schlumberger)

- Brice Parain as Le philosophe

- Henri Attal as Arthur (as Henri Atal)

- as Premier client

- as La serveuse de café

- as L'agent de police

Production[]

The film was shot over the course of four weeks for $40,000.[1][2]

Style[]

In Vivre sa vie, Godard borrowed the aesthetics of the cinéma vérité approach to documentary film-making that was then becoming fashionable. However, this film differed from other films of the French New Wave by being photographed with a heavy Mitchell camera, as opposed to the light weight cameras used for earlier films.[citation needed] The cinematographer was Raoul Coutard, a frequent collaborator of Godard.

Influences[]

This section possibly contains original research. (April 2008) |

One of the film's original sources is a study of contemporary prostitution, Où en est la prostitution by , an examining magistrate.

Vivre sa vie was released shortly after Cahiers du cinéma (the film magazine for which Godard occasionally wrote) published an issue devoted to Bertolt Brecht and his theory of 'epic theatre'. Godard may have been influenced by it, as Vivre sa vie uses several alienation effects: twelve intertitles appear before the film's 'chapters' explaining what will happen next; jump cuts disrupt the editing flow; characters are shot from behind when they are talking; they are strongly backlit; they talk directly to the camera; the statistical results derived from official questionnaires are given in a voice-over; and so on.

The film also draws from the writings of Montaigne, Baudelaire, Zola and Edgar Allan Poe, to the cinema of Robert Bresson, Jean Renoir and Carl Dreyer.[citation needed] And Jean Douchet, the French critic, has written that Godard's film "would have been impossible without Street of Shame, Kenji Mizoguchi's last and most sublime film."[3] Nana gets into an earnest discussion with a philosopher (played by Brice Parain, Godard's former philosophy tutor), about the limits of speech and written language. In the next scene, as if to illustrate this point, the sound track ceases and the images are overlaid by Godard's personal narration. This formal playfulness is typical for the way in which the director was working with sound and vision during this period.[citation needed]

The film depicts the consumerist culture of Godard's Paris; a shiny new world of cinemas, coffee bars, neon-lit pool halls, pop records, photographs, wall posters, pin-ups, pinball machines, juke boxes, foreign cars, the latest hairstyles, typewriters, advertising, gangsters and Americana. It also features allusions to popular culture; for example, the scene where a melancholy young man walks into a café, puts on a juke box disc, and then sits down to listen. The unnamed actor is in fact the well known singer-songwriter Jean Ferrat, who is performing his own hit tune "Ma Môme" on the track that he has just selected. Nana's bobbed haircut replicates that made famous by Louise Brooks in the 1928 film Pandora's Box, where the doomed heroine also falls into a life of prostitution and violent death. In one sequence we are shown a queue outside a Paris cinema waiting to see Jules et Jim, the new wave film directed by François Truffaut, at the time both a close friend and sometime rival of Godard.

The film was remade as She Lives Her Life in 2014 by director Mark Thimijan.

Reception[]

The film was the fourth most popular movie at the French box office in its year of release.[1] It won the Grand Jury Prize in 1962 Venice Film Festival.[4]

Critical response[]

Vivre sa Vie enjoys an extremely positive critical reputation. On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film currently holds an approval rating of 91% based on 32 reviews, with an average rating of 8/10.[5] Author and cultural critic Susan Sontag described it as "a perfect film" and "one of the most extraordinary, beautiful, and original works of art that I know of."[6] According to critic Roger Ebert in his essay on the film in the book The Great Movies, "The effect of the film is astonishing. It is clear, astringent, unsentimental, abrupt."[7]

Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic described My Life to Live as "empty and pretentious".[8]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Archer, Eugene (27 Sep 1964). "France's Far Out Filmmaker". New York Times. p. X11.

- ^ Sterritt, David (1999). "My Life to Live". The Films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the Invisible. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 63. ISBN 0-521-58038-2. OCLC 40632411. Archived from the original on 2021-03-28. Retrieved 2021-03-28.

- ^ Jean Douchet "French New Wave" ISBN 1-56466-057-5

- ^ "Venice Film Festival 1962". MUBI. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ "My Life to Live (It's My Life) (Vivre sa vie: Film en douze tableaux) (1962)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ Susan Sontag, On Godard's Vivre sa vie, Moviegoer, No. 2, Summer/Autumn 1964, p. 9.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (2001-04-01). "Vivre sa Vie / My Life to Live". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 2020-06-12. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- ^ Kauffmann, Stanley (1966). A world on Film. Delta Books. p. 241.

Further reading[]

- Colin MacCabe (2004) Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at Seventy, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 0-374-16378-2.

External links[]

- Vivre sa vie: Film en douze tableaux at IMDb

- Vivre sa vie at AllMovie

- Vivre sa vie: An Introduction and A to Z , (episodic essay on watching this film, with a selection of stills), Senses of Cinema, Issue 48, August 2008.

- Critical essay on Vivre sa vie, Senses of Cinema, April 2000.

- "(Post) Modern Godard: Vivre sa vie", critical essay on the modern and postmodern aspects of Vivre sa vie.

- Vivre sa vie: The Lost Girl an essay by Michael Atkinson at the Criterion Collection

- 1962 films

- French-language films

- 1962 drama films

- Films about prostitution in Paris

- Films directed by Jean-Luc Godard

- Films scored by Michel Legrand

- Films set in Paris

- French avant-garde and experimental films

- French black-and-white films

- French drama films

- French films

- Venice Grand Jury Prize winners

- 1960s avant-garde and experimental films