Bristol Hercules

| Hercules | |

|---|---|

| |

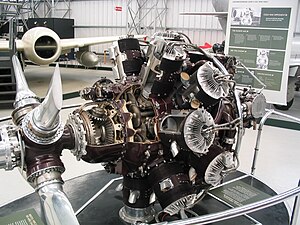

| Cutaway Bristol Hercules engine at the National Museum of Flight, East Fortune, Scotland | |

| Type | Piston aircraft engine |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Bristol Aeroplane Company |

| First run | January 1936 |

| Major applications | Bristol Beaufighter Short Stirling Handley Page Halifax |

| Number built | 57,400 |

| Developed from | Bristol Perseus |

| Developed into | Bristol Centaurus |

The Bristol Hercules is a 14-cylinder two-row radial aircraft engine designed by Sir Roy Fedden and produced by the Bristol Engine Company starting in 1939. It was the most numerous of their single sleeve valve (Burt-McCollum, or Argyll, type) designs, powering many aircraft in the mid-World War II timeframe.

The Hercules powered a number of aircraft types, including Bristol's own Beaufighter heavy fighter design, although it was more commonly used on bombers. The Hercules also saw use in civilian designs, culminating in the 735 and 737 engines for such as the Handley Page Hastings C1 and C3 and Bristol Freighter. The design was also licensed for production in France by SNECMA.

Design and development[]

Shortly after the end of World War I, the Shell company, Asiatic Petroleum, commissioned Harry Ricardo to investigate problems of fuel and engines. His book was published in 1923 as “The Internal Combustion Engine”.[1] Ricardo postulated that the days of the poppet valve were numbered and that a sleeve valve alternative should be pursued.[2]

The rationale behind the single sleeve valve design was two-fold: to provide optimum intake and exhaust gas flow in a two-row radial engine, improving its volumetric efficiency; and to allow higher compression ratios, thus improving its thermal efficiency. The arrangement of the cylinders in two-row radials made it very difficult to utilise four valves per cylinder, consequently all non-sleeve valve two- and four-row radials were limited to the less efficient two-valve configuration. Also, as combustion chambers of sleeve-valve engines are uncluttered by valves, especially the hot exhaust valves, being comparatively smooth they allow engines to work with lower octane number fuels using the same compression ratio. Conversely, the same octane number fuel may be utilised while employing a higher compression ratio, or supercharger pressure, thus attaining either higher economy, or power output. The downside was the difficulty in maintaining sufficient cylinder and sleeve lubrication.

Manufacturing was also a major problem. Sleeve valve engines, even the mono valve Fedden had elected to use, were extremely difficult to make. Fedden had experimented with sleeve valves in an inverted V-12 as early as 1927 but did not pursue that engine any further. Reverting to nine cylinder engines, Bristol had developed a sleeve valve engine that would actually work by 1934, introducing their first sleeve-valve designs in the 750 horsepower (560 kW) class Perseus and the 500 hp (370 kW) class Aquila that they intended to supply throughout the 1930s. Aircraft development in the era was so rapid that both engines quickly ended up at the low-power end of the military market and, in order to deliver larger engines, Bristol developed 14-cylinder versions of both. The Perseus evolved into the Hercules, and the Aquila into the Taurus.

These smooth-running engines were largely hand-built, which was incompatible with the needs of wartime production. At that time, the tolerances were simply not sufficiently accurate to ensure the mass production of reliable engines. Fedden drove his teams mercilessly, at both Bristol and its suppliers and thousands of combinations of alloys and methods were tried before a process was discovered which used centrifugal casting to make the sleeves perfectly round. This final success arrived just before the start of the Second World War.[3]

Bristol later tested American poppet valve Cyclone and Twin Wasp engines and found that, with new materials, the advantage of sleeve valves may not have been worth the effort. The entire development of these engines had been funded by Bristol and even with Air Ministry support, had nearly broken the company. Perhaps the greatest advantage was that the US engines had a specific weight of approximately 1.4lb/hp while the Bristol engines ran at near parity.[4]

In 1937 Bristol acquired a Northrop Model 8A-1, the export version of the A-17 attack bomber, and modified it as a testbed for the first Hercules engines.[5]

The first Hercules engines were available in 1939 as the 1,290 hp (960 kW) Hercules I, soon improved to 1,375 hp (1,025 kW) in the Hercules II. The major version was the Hercules VI which delivered 1,650 hp (1,230 kW), and the late-war Hercules XVII produced 1,735 hp (1,294 kW).

In 1939 Bristol developed a modular, "unitized" engine installation for the Hercules, a so-called "power-egg", allowing the complete engine and cowling to be fitted to any suitable aircraft.[6]

A total of over 57,400 Hercules engines were built.

Applications[]

Note:[7]

- Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle

- Avro Lancaster B.II

- Avro York C.II

- Bristol Beaufighter

- Bristol Freighter

- Bristol Superfreighter

- Breguet 890 Mercure

- CASA C-207 Azor

- Fokker T.IX

- Folland Fo.108

- Handley Page Halifax

- Handley Page Hastings

- Handley Page Hermes

- Nord Noratlas

- Northrop 8A (One Swedish 8A-1 was bought by Bristol to test the engine)

- Northrop Gamma 2L

- Saro Lerwick

- Short S.26

- Short Seaford

- Short Solent

- Short Stirling

- Vickers Valetta

- Vickers Varsity

- Vickers VC.1 Viking

- Vickers Wellesley

- Vickers Wellington

Specifications (Hercules II)[]

Data from Lumsden.[8]

General characteristics

- Type: 14-cylinder, two-row, supercharged, air-cooled radial engine

- Bore: 5.75 in (146 mm)

- Stroke: 6.5 in (165 mm)

- Displacement: 2,360 in³ (38.7 L)

- Length: 53.15 in (1,350 mm)

- Diameter: 55 in (1,397 mm)

- Dry weight: 1,929 lb (875 kg)

Components

- Valvetrain: Gear-driven sleeve valves with five ports per sleeve — three intake and two exhaust

- Supercharger: Single-speed centrifugal type supercharger

- Fuel system: Claudel-Hobson carburettor

- Fuel type: 87 Octane petrol

- Cooling system: Air-cooled

- Reduction gear: Farman epicyclic gearing, 0.44:1

Performance

- Power output:

- 1,272 hp (949 kW) at 2,800 rpm for takeoff

- 1,356 hp (1,012 kW) at 2,750 rpm at 4,000 ft (1,220 m)

- Specific power: 0.57 hp/in³ (26.15 kW/l)

- Compression ratio: 7.0:1

- Specific fuel consumption: 0.43 lb/(hp•h) (261 g/(kW•h))

- Power-to-weight ratio: 0.7 hp/lb (1.16 kW/kg)

See also[]

Related development

Comparable engines

- BMW 801

- Pratt & Whitney R-1830

- Pratt & Whitney R-2000

- Wright R-2600

- Fiat A.74

- Fiat A.80

- Gnome-Rhône 14N

- Mitsubishi Kinsei

- Nakajima Sakae

- Shvetsov ASh-82

Related lists

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ The Development of Piston Aero Engines” Bill Gunston, Haynes Publishing, Somerset, 1993, p.32

- ^ Gunston, p.151

- ^ Gunston, p.151

- ^ Gunston, p.152

- ^ "Something Up Its Sleeve." Flight, 7 October 1937, p. 359.

- ^ http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1939/1939-1-%20-%201270.html[dead link]

- ^ List from Lumsden 2003, some of these aircraft were used for test purposes, the Hercules not necessarily being the main powerplant

- ^ Lumsden 2003, p.119.

Bibliography[]

- Bridgman, Leonard, ed. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1945–1946. London: Samson Low, Marston & Company, Ltd 1946.

- Gunston, Bill. (1993) The Development of Piston Aero Engines, Haynes Publishing, Somerset ISBN 1-85260-385-2

- Gunston, Bill. (1995) Classic World War II Aircraft Cutaways. Osprey. ISBN 1-85532-526-8

- Gunston, Bill. World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines: From the Pioneers to the Present Day. 5th edition, Stroud, UK: Sutton, 2006. ISBN 0-7509-4479-X

- Lumsden, Alec. British Piston Engines and Their Aircraft. Marlborough, UK: Airlife Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-85310-294-6.

- White, Graham. Allied Aircraft Piston Engines of World War II: History and Development of Frontline Aircraft Piston Engines Produced by Great Britain and the United States During World War II. Warrendale, Pennsylvania: SAE International, 1995. ISBN 1-56091-655-9

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bristol Hercules. |

- Running a Hercules for the first time in 30 years

- Image of the gear system for the sleeve drive

- "Safety through engine development testing" a 1948 advert for the Hercules in Flight magazine

- "600 Hours between overhaul" a 1948 Flight advertisement for the Hercules

- Bristol aircraft engines

- Aircraft air-cooled radial piston engines

- Sleeve valve engines

- 1930s aircraft piston engines