Byōbu

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

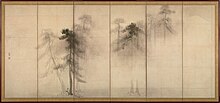

Byōbu (屏風) (lit., "wind wall") are Japanese folding screens made from several joined panels, bearing decorative painting and calligraphy, used to separate interiors and enclose private spaces, among other uses.

History[]

Byōbu are thought to have originated in Han dynasty China and are thought to have been imported to Japan in the 7th or 8th century. The oldest surviving byōbu produced in Japan, the torige ritsujo no byōbu (鳥毛立女屏風), produced in the 8th century, is kept in the Shōsōin Treasure Repository.[1] Following the Heian period and the independent development of Japan's culture separate from mainland Asian infleunces, the design of byōbu developed further from previously Chinese influences, and came to be used as furnishings in the architectural style of Shinden-zukuri

- Nara period (646–794): The original form of byōbu was a single standing, legged panel. In the 8th century, multi-paneled byōbu made their appearance, and were used as furnishings in the imperial court, mainly in important ceremonies. The six-paneled byōbu were the most common in the Nara period, and were covered in silk and connected with leather or silk cords. The painting on each panel was framed by a silk brocade, and the panel was bound with a wood frame.

- Heian period (794–1185): By the 9th century, byōbu were indispensable as furniture in the residences of daimyō, Buddhist temples, and shrines. Zenigata (銭形), coin-shaped metal hinges, were introduced and widely used to connect the panels instead of silk cords.

- Muromachi period (1392–1568): Folding screens became more popular and were found in many residences, dojo, and shops. Two-panel byōbu were common, and overlapped paper hinges substituted for zenigata, which made them lighter to carry, easier to fold, and stronger at the joints. This technique allowed the depictions in the byōbu to be uninterrupted by panel vertical borders, which prompted artists to paint sumptuous, often monochromatic, nature-themed scenes and landscapes of famous Japanese locales. The paper hinges, although quite strong, required that the panel infrastructure be as light as possible. Softwood lattices were constructed using special bamboo nails that allowed for the lattice to be planed along its edges to be straight, square, and the same size as the other panels of the byōbu. The lattices were coated with one or more layers of paper stretched across the lattice surface like a drum head to provide a flat and strong backing for the paintings that would be later mounted on the byōbu. The resulting structure was lightweight and durable, yet still quite delicate. After the paintings and brocade were attached, a lacquered wood frame (typically black or dark red) was applied to protect the outer perimeter of the byōbu, and intricately decorated metal hardware (strips, right angles, and studs) were applied to the frame to protect the lacquer.

- Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568–1600) and early Edo period (1600–1868): byōbu popularity grew, as the people's interest in arts and crafts significantly developed during this period. Byōbu adorned samurai residences, conveying high rank and demonstrating wealth and power. This led to radical changes in byōbu crafting, such as backgrounds made from gold leaf (金箔, kinpaku) and highly colorful paintings depicting nature and scenes from daily life, a style pioneered by the Kanō school.

- Modern period: today, byōbu are often machine-made, however hand-crafted byōbu are still available, mainly produced by families that preserve the crafting traditions.

Japonism[]

The screens were a popular Japonism import item to Europe and America starting in the late 19th century. The French painter Odilon Redon created a series of panels for the Château de Domecy-sur-le-Vault in Burgundy, which were influenced by the art of byōbu.[2]

References[]

- ^ 鳥毛立女屏風 第1扇 Imperial Househpld Agency

- ^ "Musée d'Orsay: non_traduit". www.musee-orsay.fr.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Byōbu. |

- Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System Byoubu entry

- Momoyama, Japanese Art in the Age of Grandeur, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on byōbu

- Byobu: The Grandeur of Japanese Screens, a companion Web site to an exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery, which contains images and descriptions of noteworthy byōbu.

- Byōbu

- Partitions in traditional Japanese architecture

- Portable furniture