Byrdmaniax

| Byrdmaniax | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by The Byrds | ||||

| Released | June 23, 1971 | |||

| Recorded | June 2, October 6, 1970, January 9–26, March 1–6, 1971, Columbia Studios, Hollywood, CA Orchestral overdubs: mid–March – early April 1971, Columbia Studios, Hollywood, CA | |||

| Genre | Rock, country rock | |||

| Length | 34:06 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | Terry Melcher, Chris Hinshaw | |||

| The Byrds chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Byrdmaniax | ||||

| ||||

Byrdmaniax is the tenth album by the American rock band the Byrds. It was released in June 1971 on Columbia Records (see 1971 in music)[1] at a time of renewed commercial and critical success for the band, due to the positive reception that their two previous albums, Ballad of Easy Rider and (Untitled), had received.[2][3] The album was the second by the Byrds to feature the Roger McGuinn, Clarence White, Gene Parsons, and Skip Battin line-up of the band and was mostly recorded in early 1971, while the band were in the midst of an exhausting tour schedule.[2][4] As a result, the band had little time to hone their new songs before recording commenced and thus, much of the material on the album is underdeveloped.[2] Byrdmaniax was poorly received upon release, particularly in the United States, and did much to undermine the Byrds' new-found popularity.[2]

The album peaked at #46 on the Billboard Top LPs chart but failed to reach the UK Albums Chart.[5][6] The song "I Trust (Everything Is Gonna Work Out Alright)" was released as a preceding single on May 7, 1971 in the United Kingdom but it did not chart.[1][6] A second single taken from the album, "Glory, Glory", was released on August 20, 1971 and reached #110 on the Billboard chart, but again, the single failed to reach the UK chart.[7] Byrdmaniax remains one of the Byrds most poorly received album releases, largely due to the incongruous addition of strings, horns, and a gospel choir which were overdubbed onto the songs by producer Terry Melcher and arranger Paul Polena, reportedly without the band's consent.[2][8]

Overview[]

After the release of the Byrds' (Untitled) album, the band continued to tour extensively throughout late 1970 and early 1971 in support of the record.[9] With the band's career experiencing a revival of commercial fortunes, the Byrds elected to continue working with Terry Melcher, who had produced the band's two previous albums.[10][11] Unfortunately, the grueling pace of the band's touring schedule meant that they were under-prepared for the recording of their next album, with little or no time to develop the material that they intended to include.[2] Sessions for Byrdmaniax commenced on October 6, 1970, just three weeks after the release of (Untitled), and continued throughout January and March 1971, with the band recording twelve new songs as well as revisiting an outtake from the (Untitled) sessions, "Kathleen's Song".[12][13] The album's pre-release working title was Expensive, a tongue-in-cheek reference to the bloated costs incurred during the recording of the album, but ultimately this was dropped in favor of the less opulent sounding Byrdmaniax.[14]

Music[]

Among guitarist Roger McGuinn's songwriting contributions to the album was the modal acoustic ballad "Pale Blue" (co-written with drummer Gene Parsons).[13] The song's title can be seen as a metaphor for a mood, while its romantic lyrics deal with the conflicting themes of freedom and security.[15][16] With its melancholy sense of longing, folksy instrumentation, and sensitive lead vocal performance, "Pale Blue" is often regarded by critics as being one of the most successful musical statements on the album as well as something of a lost classic among the Byrds' oeuvre.[15][16] Another McGuinn-penned song included on Byrdmaniax was the commercially unsuccessful, quasi-gospel single "I Trust" (re-titled as "I Trust (Everything Is Gonna Work Out Alright)" for the single release).[1] The song's title and lyrical refrain was inspired by McGuinn's personal catchphrase, "I trust everything will turn out alright", which itself had been borrowed by the guitarist during the mid-1960s from the best-selling book The Power of Positive Thinking by Norman Vincent Peale.[13]

McGuinn's other compositional contributions to Byrdmaniax were two songs that he had written with lyricist Jacques Levy for the pair's aborted Broadway musical, Gene Tryp.[2] Of these, "Kathleen's Song" had originally been intended for a scene in which the song's eponymous heroine patiently waits for Gene Tryp, her lover, to return home from his travels.[17] "Kathleen's Song" had, in fact, been recorded in June 1970 during the recording sessions for (Untitled) but had been omitted from that album at the eleventh hour, due to a lack of space.[18][19] As a result, there are promo copies of (Untitled) known to exist that list the song (under the abbreviated title "Kathleen") on the album sleeve.[13][20] The Byrds returned to "Kathleen's Song" in January and March 1971, undertaking additional recording work in order to ready the track for release on Byrdmaniax.[13][18] The second Gene Tryp song included on the album was "I Wanna Grow Up to Be a Politician", a whimsical ragtime pastiche that had been written for a scene in the musical in which the hero, Gene Tryp, runs as a presidential candidate.[11][21][22] The song found a second lease of life away from the confines of Gene Tryp, however, when its satirical lyrics found favor with America's radical youth, who were rebelling against the Nixon administration during the early 1970s.[13]

Byrdmaniax also included a pair of novelty songs penned by the band's bass player, Skip Battin, and his songwriting partner Kim Fowley.[2] The first of these, "Tunnel of Love", was an organ driven Fats Domino pastiche, while the second, "Citizen Kane", served as a wry comment on Hollywood life and its celebrity legacy during the 1940s and 1950s.[11][16][23] Unfortunately, the inclusion of these two songs, along with McGuinn and Levy's jaunty "I Wanna Grow Up to Be a Politician", caused the album to suffer from an overabundance of pastiche and whimsy.[2] A third Battin–Fowley song, "Absolute Happiness", was more serious, with its dramatic lyrics providing a Buddhism-inspired meditation on positive values and the power of nature.[16][24]

The album's opening track, "Glory, Glory", was borrowed by drummer Gene Parsons from the repertoire of The Art Reynolds Singers, just as "Jesus Is Just Alright" on Ballad of Easy Rider had been.[16][25] Despite featuring a striking piano part and strong gospel backing vocals, the song lacked the immediacy of "Jesus Is Just Alright", as producer Terry Melcher admitted in a 1977 interview: "We were aiming to cut another 'Jesus Is Just Alright', but we didn't make it. Larry Knechtel played piano on this cut but it was too fast. The whole thing was a mess."[16][17] The album also included a bluegrass instrumental named "Green Apple Quick Step", written by Parsons and lead guitarist Clarence White, which featured guest musicians Eric White, Sr. (Clarence's father) on harmonica and Byron Berline on fiddle.[16] White also brought the Helen Carter song "My Destiny" to the recording sessions, having first learned it during his days as a bluegrass musician.[13][17] White elected to sing lead vocal on the track but unfortunately his nasal voice and the band's lackluster musical backing gave the recording a fatalistic and dirge-like quality.[13] The final track on Byrdmaniax was a rendition of "Jamaica Say You Will", written by the then unknown Jackson Browne and featuring a Clarence White vocal performance that is widely regarded as one of his best on a Byrds' album.[11][26]

In addition to the eleven songs included on the original LP, at least two outtakes from the album sessions are known to exist: a recording of Bob Dylan's "Just Like a Woman"—which had also been attempted during the (Untitled) recording sessions—and a cover of ex-Byrd Gene Clark's "Think I'm Gonna Feel Better".[13] Both songs remained in the Columbia vaults for almost 29 years, before finally being released in 2000 as bonus tracks on the Columbia/Legacy reissue of Byrdmaniax.[13] The version of "Just Like a Woman" recorded for the album in 1971 represented the last Dylan song that the Byrds would record until "Paths of Victory", during the 1990 reunion sessions that were included on The Byrds box set. A third outtake from the album sessions that is rumored to exist is the Parsons–White composition "Blue Grease".[14] This song was included in a pre-release track listing for the album that was published in the Byrds' fanclub newsletter, The Byrds Bulletin, in early 1971.[14] However, the track failed to appear on the album and may not have even been recorded by the band, since there is no mention of it in the Columbia files or in contemporary studio documentation.[14]

Post-production[]

Following the completion of recording sessions for the album in early March 1971, the Byrds headed out on tour again, leaving Terry Melcher and engineer Chris Hinshaw to finish mixing the album.[8][14] In the Byrds' absence, Melcher and Hinshaw brought in arranger Paul Polena to assist with the overdubbing of strings, horns, and a gospel choir onto many of the songs, at a reported cost of $100,000 and allegedly without the band's consent.[8][11][14] When the band heard the extent of Melcher's additions they protested to Columbia Records, campaigning to have the album remixed and the orchestration removed but the record company held firm, citing budget restrictions, and the record was duly pressed up and released.[9]

For his part, Melcher defended his actions by explaining that the band's performances in the studio were lackluster and that the orchestration was needed to cover up the album's musical shortcomings.[11] In a 1977 interview with the Byrds' biographer Johnny Rogan, Melcher attempted to illustrate the situation in the recording studio during the making of the album and also explain his rationale for the orchestral additions: "Several members of the group were involved in divorces and they were hiding from their wives. It was complete bedlam in the studio. Everyone had too many problems. There was a lack of interest on everybody's part. I was trying to save the album, but it was a mistake. I should have called a halt."[9] Melcher also succinctly highlighted his lack of confidence in the quality of the material that the band had recorded: "I think the orchestration was a big mistake, but the songs were weak."[9] As for not obtaining the band's consent for the overdubs, Melcher explained "I admit that I wasn't in consultation with them a lot and I didn't really deal with Clarence, Battin or Parsons on these matters. But I'm sure it was inconceivable that McGuinn did not know about the orchestration."[9]

The band themselves were far from happy with the album and upon its release, were vocal in press interviews about their dissatisfaction.[9] Even two years later, Clarence White complained to journalist Pete Frame that "Terry Melcher put strings on while we were on the road, we came back and we didn't even recognize it as our own album."[9] Gene Parsons disowned the album completely, describing it as "Melcher's folly" and commenting in interviews that the band were all appalled by what they heard when they returned from touring.[9] McGuinn actually defended Melcher somewhat by indicating in an interview with the English journalist Keith Altham that the album had been taken away from the producer at the last minute and given to an engineer in San Francisco to remix.[9][14] However, the production credits on the original LP sleeve do not support McGuinn's claim and Melcher later stated that he had no recollection of the album being mixed by anyone other than himself.[9] In more recent years, McGuinn has conceded to journalist David Fricke that the album's shortcomings were not down to Melcher's over-production alone: "We were just idling artistically, the album sounds like we really weren't concentrating on doing good work, good art."[2]

Release and reception[]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B–[27] |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Entertainment Weekly | B+[29] |

Byrdmaniax was released on June 23, 1971 in the United States (catalogue item KC 30640) and August 6, 1971 in the United Kingdom (catalogue item S 64389).[1] Although the album was issued in stereo commercially, there is some evidence to suggest that mono copies of the album (possibly radio station promos) were distributed in the UK.[1][30] As well as being issued in the standard stereo format, Byrdmaniax was also released in 1971 as a Quadraphonic LP in Japan on the CBS Sony label (catalogue item SOPL-34001).[20][31] The quadraphonic version of the album features a noticeably different mix to the standard stereo version.

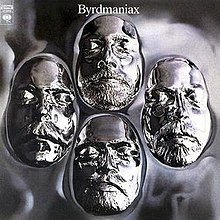

The album peaked at #46 on the Billboard Top LPs chart, during a chart stay of ten weeks, but failed to chart in the UK.[6][32] A single, "I Trust (Everything Is Gonna Work Out Alright)" b/w "(Is This) My Destiny", was released ahead of the album on May 7, 1971 in the UK, to coincide with a European tour, but it did not chart.[6][9] A second single taken from the album, "Glory, Glory" (b/w "Citizen Kane"), was released on August 20, 1971 and reached #110 on the Billboard chart but again failed to chart in the UK.[7] The album cover artwork, featuring a set of silver "death masks"—one for each member of the band—was designed by Virginia Team and Grammy Award-winning Columbia Records' art director, John Berg.[2][33][34] These foreboding plaster facemasks, which were created by artist Mary Leonard and photographed by Don Jim, have been regarded by some critics as an accurate visual representation of the lifeless music on the album and the declining state of the band in 1971.[2][14][35][33]

Upon its release, Byrdmaniax was greeted positively by the UK music press but received scathing reviews in the U.S.[9] Richard Meltzer's review in the August 1971 edition of Rolling Stone magazine was particularly vicious, with Meltzer describing the album as "increments of pus". The same review also described the McGuinn–Levy composition "I Wanna Grow Up to Be a Politician" as a song that was "degenerating into namby pamby innocuous mickey mouse with latent-blatant political content".[36] Meltzer concluded his withering attack by deriding the Byrds themselves as "a boring dead group."[36] In the UK, Roy Hollingworth's review in the August 14, 1971 edition of Melody Maker was more positive and described the album as "one sweet length of bursting Byrds sunshine, so perfect in quality and quantity you'd feel an absolute heel to ask for more."[7] Record Mirror was also enthusiastic in its praise of the album, describing it as "another fine album by the Byrds."[7] However, not all British reviews of Byrdmaniax were positive, with Richard Green of the NME noting that "When the true history of rock comes to be written, the Byrds will get a deserved place of honour on the strength of tunes like 'Mr. Tambourine Man', 'Eight Miles High', and 'So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star'. Hopefully the writer will not have listened to Byrdmaniax or he may drastically alter his opinion."[7] Green was also critical of Terry Melcher's use of strings and horns on many of the tracks, concluding that "Orchestration is all very well for some bands, but not, on this showing, for the Byrds."[7]

Today, Byrdmaniax is generally regarded as the Byrds' weakest album, as well as the least popular of any of the band's releases amongst their fanbase.[7] Mark Deming, writing for the AllMusic website, has summed up the album by concluding "Not an awful album, but Byrdmaniax is hardly the pleasure it could have been in the hands of a more tasteful production team."[8] In his 2000 review for The Austin Chronicle, Raoul Hernandez gave the album a rating of three stars out of five, commenting "Byrdmaniax may be as disjointed as reviews claimed at the time, but most of these same critics didn't like Sweetheart of the Rodeo either, and if the Gram Parsons-blessed classic is ground zero for 'country rock' then Maniax is full-blown 'gospel rock'."[37] Rolling Stone senior editor David Fricke remarked in 2000 that Byrdmaniax suffered not just from Melcher's inappropriate orchestration, but also from being a Byrds' album that is almost totally bereft of the Byrds' signature sound.[2] According to Fricke, the familiar chime of McGuinn's 12-string Rickenbacker guitar is lost beneath the overbearing strings and the band's trademark harmonies are also largely absent from the album.[2]

Byrdmaniax was remastered at 20-bit resolution as part of the Columbia/Legacy Byrds series. It was reissued in an expanded form on February 22, 2000 with three bonus tracks. These bonus tracks included an outtake version of Gene Clark's "Think I'm Gonna Feel Better", sung by Clarence White (who had also played guitar on Clark's original 1967 solo recording of the song); a stripped-down alternate version of "Pale Blue"; and a rendition of Bob Dylan's "Just Like a Woman".[13] The remastered reissue also includes, as a hidden track, an alternate version of "Green Apple Quick Step", which is sometimes known by the alternate title "Byrdgrass".[38] Byrdmaniax was again reissued in Japan in the High Definition audio format on February 14, 2014. Bonus tracks Include the Mono promotional single version of 'Glory, Glory', a live version of 'I Trust', the previously released bonus tracks of 'Think I'm Gonna Feel better' and 'Just Like A Woman', and a newly uncovered studio song 'Nothin' To it'. The disc comes in a cd-sized gatefold paper sleeve album replica (Mini LP) with obi strip and booklet insert of notes (mostly in Japanese). Actual track durations are given in the booklet insert.

Track listing[]

Side 1[]

- "Glory, Glory" () – 4:03

- "Pale Blue" (Roger McGuinn, Gene Parsons) – 2:22

- "I Trust" (Roger McGuinn) – 3:19

- "Tunnel of Love" (Skip Battin, Kim Fowley) – 4:59

- "Citizen Kane" (Skip Battin, Kim Fowley) – 2:36

Side 2[]

- "I Wanna Grow Up to Be a Politician" (Roger McGuinn, Jacques Levy) – 2:03

- "Absolute Happiness" (Skip Battin, Kim Fowley) – 2:38

- "Green Apple Quick Step" (Gene Parsons, Clarence White) – 1:49

- "My Destiny" (Helen Carter) – 3:38

- "Kathleen's Song" (Roger McGuinn, Jacques Levy) – 2:40

- "Jamaica Say You Will" (Jackson Browne) – 3:27

2000 CD reissue bonus tracks[]

- "Just Like a Woman" (Bob Dylan) - 3:56

- "Pale Blue" [Alternate Version] (Roger McGuinn, Gene Parsons) - 2:33

- "Think I'm Gonna Feel Better" (Gene Clark) - 6:04

- NOTE: this song ends at 2:33; at 2:45 begins "Green Apple Quick Step" [Alternate Version] (Gene Parsons, Clarence White)

Singles[]

- "I Trust (Everything Is Gonna Work Out Alright)" b/w "(Is This) My Destiny" (CBS 7253) May 7, 1971

- "Glory, Glory" b/w "Citizen Kane" (Columbia 45440) August 20, 1971 (US #110)

Personnel[]

NOTES:

- Sources for this section are as follows:[12][13][14][17][18]

- Track numbers refer to CD and digital releases of the album.

- On bonus track 12 Larry Knechtel plays organ and Jackson Browne plays piano; on bonus track 14 Jimmi Seiter plays tambourine.

|

|

Release history[]

| Date | Label | Format | Country | Catalog | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 23, 1971 | Columbia | LP | US | KC 30640 | Original release. |

| August 6, 1971 | CBS | LP | UK | S 64389 | Original release. |

| 1971 | CBS Sony | LP | Japan | SOPL-34001 | Quadraphonic LP release. |

| 1992 | Line | CD | Germany | 900930 | Original CD release. |

| 1993 | Columbia | CD | US | CK 30640 | |

| 1993 | Columbia | CD | UK | COL 468429 | |

| February 22, 2000 | Columbia/Legacy | CD | US | CK 65848 | Reissue containing three bonus tracks and the remastered album. |

| UK | COL 495079 | ||||

| 2003 | Sony | CD | Japan | MHCP-105 | Reissue containing three bonus tracks and the remastered album in a replica gatefold LP sleeve. |

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 542–547. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Fricke, David. (2000). Byrdmaniax (2000 CD liner notes).

- ^ Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965-1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 226–227. ISBN 1-906002-15-0.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. (1990). The Byrds (1990 CD box set liner notes).

- ^ "The Byrds Billboard Albums". Allmusic. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965-1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 275–279. ISBN 1-906002-15-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965-1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 282–283. ISBN 1-906002-15-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Byrdmaniax review". AllMusic. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 319–321. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. p. 310. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Byrdmaniax". ByrdWatcher: A Field Guide to the Byrds of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 2009-05-29. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965-1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 253–256. ISBN 1-906002-15-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Rogan, Johnny. (2000). Byrdmaniax (2000 CD liner notes).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965-1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 268–270. ISBN 1-906002-15-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pale Blue review". Allmusic. Retrieved 2010-03-21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 321–325. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hjort, Christopher. (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965-1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 264–265. ISBN 1-906002-15-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 628–629. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ Scoppa, Bud. (1971). The Byrds. Scholastic Corporation. p. 154.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Byrds Rare LPs". Byrds Flyght. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ^ "I Wanna Grow Up to Be a Politician review". Allmusic. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny. (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. p. 316. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ "Citizen Kane review". Allmusic. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ "Absolute Happiness review". Allmusic. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ^ "Glory, Glory review". Allmusic. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ^ "Jamaica Say You Will review". Allmusic. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: B". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved February 22, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2007). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195313734.

- ^ "Byrdmaniax review". Entertainment Weekly. February 25, 2000. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ "The Byrds Mono Pressings". Byrds Flyght. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ^ "The Byrds - Byrdmaniax Quadraphonic LP product information". Esprit International Ltd. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel. (2002). Top Pop Albums 1955-2001. Record Research Inc. p. 122. ISBN 0-89820-147-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Byrdmaniax credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ^ "John Berg: The Man Behind The Album Covers". The East Hampton Star. Archived from the original on 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ^ "Byrdmaniax review". Blender. Archived from the original on 2009-04-20. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Byrdmaniax review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ^ "The Byrds Record Reviews". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ^ Irwin, Bob. (2006). There Is a Season (2006 CD box set liner notes).

Bibliography[]

- Rogan, Johnny, The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited, Rogan House, 1998, ISBN 0-9529540-1-X

- Hjort, Christopher, So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965-1973), Jawbone Press, 2008, ISBN 1-906002-15-0.

- 1971 albums

- The Byrds albums

- Albums produced by Terry Melcher

- Columbia Records albums

- CBS Records albums

- Legacy Recordings albums