CITES

| The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora | |

|---|---|

| |

| Signed | 3 March 1973 |

| Location | |

| Effective | 1 July 1975 |

| Condition | 10 ratifications |

| Parties | 183 |

| Depositary | |

| Language | |

CITES (shorter name for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals. It was drafted as a result of a resolution adopted in 1963 at a meeting of members of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The convention was opened for signature in 1973 and CITES entered into force on 1 July 1975.

Its aim is to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten the survival of the species in the wild, and it accords varying degrees of protection to more than 35,000 species of animals and plants. In order to ensure that the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was not violated, the Secretariat of GATT was consulted during the drafting process.[1]

As of 2018, Secretary-General of the CITES Secretariat is Ivonne Higuero.[2]

Background and operation[]

CITES is one of the largest and oldest conservation and sustainable use agreements in existence. Participation is voluntary, and countries that have agreed to be bound by the convention are known as Parties. Although CITES is legally binding on the Parties, it does not take the place of national laws. Rather it provides a framework respected by each Party, which must adopt their own domestic legislation to implement CITES at the national level. Often, domestic legislation is either non-existent (especially in Parties that have not ratified it), or with penalties with the gravity of the crime and insufficient deterrents to wildlife traders.[3] As of 2002, 50% of Parties lacked one or more of the four major requirements for a Party: designation of Management and Scientific Authorities; laws prohibiting the trade in violation of CITES; penalties for such trade; laws providing for the confiscation of specimens.[4]

Funding for the activities of the Secretariat and Conference of the Parties (CoP) meetings comes from a Trust Fund derived from Party contributions. Trust Fund money is not available to Parties to improve implementation or compliance. These activities, and all those outside Secretariat activities (training, species specific programmes such as Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants – MIKE) must find external funding, mostly from donor countries and regional organizations such as the European Union.

Although the Convention itself does not provide for arbitration or dispute in the case of noncompliance, 36 years of CITES in practice has resulted in several strategies to deal with infractions by Parties. The Secretariat, when informed of an infraction by a Party, will notify all other parties. The Secretariat will give the Party time to respond to the allegations and may provide technical assistance to prevent further infractions. Other actions the Convention itself does not provide for but that derive from subsequent COP resolutions may be taken against the offending Party. These include:

- Mandatory confirmation of all permits by the Secretariat

- Suspension of cooperation from the Secretariat

- A formal warning

- A visit by the Secretariat to verify capacity

- Recommendations to all Parties to suspend CITES related trade with the offending party[5]

- Dictation of corrective measures to be taken by the offending Party before the Secretariat will resume cooperation or recommend resumption of trade

Bilateral sanctions have been imposed on the basis of national legislation (e.g. the USA used certification under the Pelly Amendment to get Japan to revoke its reservation to hawksbill turtle products in 1991, thus reducing the volume of its exports).

Infractions may include negligence with respect to permit issuing, excessive trade, lax enforcement, and failing to produce annual reports (the most common).

Originally, CITES addressed depletion resulting from demand for luxury goods such as furs in Western countries, but with the rising wealth of Asia, particularly in China, the focus changed to products demanded there, particularly those used for luxury goods such as ivory or shark fins or for superstitious purposes such as rhinoceros horn. As of 2013 the demand was massive and had expanded to include thousands of species previously considered unremarkable and in no danger of extinction such as manta rays or pangolins.[6]

- CITES compliance is complicated by the similarity of some banned species to permitted species, and by the diverse appearance of specimens of the same species

Samples of wood of three species including mahogany, looking similar

Three samples of teak wood from different countries, looking different

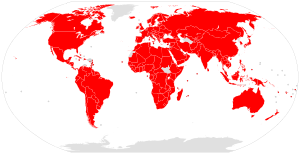

Ratifications[]

The text of the convention was finalized at a meeting of representatives of 80 countries in Washington, D.C., United States, on 3 March 1973. It was then open for signature until 31 December 1974. It entered into force after the 10th ratification by a signatory country, on 1 July 1975. Countries that signed the Convention become Parties by ratifying, accepting or approving it. By the end of 2003, all signatory countries had become Parties. States that were not signatories may become Parties by acceding to the convention. As of October 2016, the convention has 183 parties, including 182 states and the European Union.[8]

The CITES Convention includes provisions and rules for trade with non-Parties. All member states of the United Nations are party to the treaty, with the exception of Andorra, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Federated States of Micronesia, Haiti, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, South Sudan, East Timor, Turkmenistan, and Tuvalu. UN observer the Holy See is also not a member. The Faroe Islands, an autonomous country in the Kingdom of Denmark, is also treated as a non-Party to CITES (both the Danish mainland and Greenland are part of CITES).[7][9]

An amendment to the text of the convention, known as the Gaborone Amendment[10] allows regional economic integration organizations (REIO), such as the European Union, to have the status of a member state and to be a Party to the convention. The REIO can vote at CITES meetings with the number of votes representing the number of members in the REIO, but it does not have an additional vote.

In accordance with Article XVII, paragraph 3, of the CITES Convention, the Gaborone Amendment entered into force on 29 November 2013, 60 days after 54 (two-thirds) of the 80 States that were party to CITES on 30 April 1983 deposited their instrument of acceptance of the amendment. At that time it entered into force only for those States that had accepted the amendment. The amended text of the convention will apply automatically to any State that becomes a Party after 29 November 2013. For States that became party to the convention before that date and have not accepted the amendment, it will enter into force 60 days after they accept it.[11]

Regulation of trade[]

CITES works by subjecting international trade in specimens of selected species to certain controls. All import, export, re-export and introduction from the sea of species covered by the convention has to be authorized through a licensing system. According to Article IX of the convention, Management and Scientific Authorities, each Party to the Convention must designate one or more Management Authorities in charge of administering that licensing system and one or more Scientific Authorities to advise them on the effects of trade on the status of CITES-listed species.

Appendices[]

Roughly 5,000 species of animals and 29,000 species of plants are protected by CITES against over-exploitation through international trade. Each protected species or population is included in one of three lists, called appendices[12][13] (explained below). The Appendix that lists a species or population reflects the extent of the threat to it and the controls that apply to the trade.

Species may be split-listed meaning that some populations of a species are on one Appendix, while some are on another. Some people argue that this is risky as specimens from a more protected population could be 'laundered' through the borders of a Party whose population is not as strictly protected. The African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana) is currently split-listed, with all populations except those of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe listed in Appendix I. Those of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe are listed in Appendix II. Listing the species over the whole of its range would prevent such 'laundering' but also restricts trade in wildlife products by range states with good management practices. There are also species that have only some populations listed in an Appendix. One example is the pronghorn (Antilocapra americana), a ruminant native to North America. Its Mexican population is listed in Appendix I, but its U.S. and Canadian populations are not listed (though certain U.S. populations in Arizona are nonetheless protected under the Endangered Species Act).

Species are proposed for inclusion in or deletion from the Appendices at meetings of the Conference of the Parties (CoP), which are held approximately once every three years.[14]

Species in the Appendices may be proposed for addition, change of Appendix, or de-listing (i.e., deletion) by any Party, whether or not it is a range State and changes may be made despite objections by range States if there is sufficient (2/3 majority) support for the listing. These discussions are usually among the most contentious at CoP meetings.

There has been increasing willingness within the Parties to allow for trade in products from well-managed populations. For instance, sales of the South African white rhino have generated revenues that helped pay for protection. Listing the species on Appendix I increased the price of rhino horn (which fueled more poaching), but the species survived wherever there was adequate on-the-ground protection. Thus field protection may be the primary mechanism that saved the population, but it is likely that field protection would not have been increased without CITES protection.[15]

Appendix I[]

Appendix I, about 1200 species, are species that are threatened with extinction and are or may be affected by trade. Commercial trade in wild-caught specimens of these species is illegal (permitted only in exceptional licensed circumstances). Captive-bred animals or cultivated plants of Appendix I species are considered Appendix II specimens, with concomitant requirements (see below and Article VII). The Scientific Authority of the exporting country must make a non-detriment finding, assuring that export of the individuals will not adversely affect the wild population. Any trade in these species requires export and import permits. The Management Authority of the exporting state is expected to check that an import permit has been secured and that the importing state is able to care for the specimen adequately.

Notable animal species listed in Appendix I include the red panda (Ailurus fulgens), western gorilla (Gorilla gorilla), the chimpanzee species (Pan spp.), tigers (Panthera tigris subspecies), Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica), leopards (Panthera pardus), jaguar (Panthera onca), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), some populations of African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana),[a] the dugong and manatees (Sirenia), and all rhinoceros species (except some Southern African subspecies populations).[16]

Appendix II[]

Appendix II, about 21,000 species, are species that are not necessarily threatened with extinction, but may become so unless trade in specimens of such species is subject to strict regulation in order to avoid utilization incompatible with the survival of the species in the wild. In addition, Appendix II can include species similar in appearance to species already listed in the Appendices. International trade in specimens of Appendix II species may be authorized by the granting of an export permit or re-export certificate. In practice, many hundreds of thousands of Appendix II animals are traded annually.[17] No import permit is necessary for these species under CITES, although some Parties do require import permits as part of their stricter domestic measures. A non-detriment finding and export permit are required by the exporting Party.[16]

In addition, Article VII of CITES states that specimens of animals listed in Appendix I that are bred in captivity for commercial purposes are treated as Appendix II. The same applies for specimens of Appendix I plants artificially propagated for commercial purposes.[18]

Examples of species listed on Appendix II are the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), the American black bear (Ursus americanus), Hartmann's mountain zebra (Equus zebra hartmannae), green iguana (Iguana iguana), queen conch (Strombus gigas), Emperor scorpion (Pandinus imperator), Mertens' water monitor (Varanus mertensi), bigleaf mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) and lignum vitae "ironwood" (Guaiacum officinale).

Appendix III[]

Appendix III, about 170 species, are species that are listed after one member country has asked other CITES Parties for assistance in controlling trade in a species. The species are not necessarily threatened with extinction globally. In all member countries, trade in these species is only permitted with an appropriate export permit and a certificate of origin from the state of the member country who has listed the species.[16]

Examples of species listed on Appendix III and the countries that listed them are the two-toed sloth (Choloepus hoffmanni) by Costa Rica, sitatunga (Tragelaphus spekii) by Ghana, African civet (Civettictis civetta) by Botswana, and alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii) by the USA.

Annex A, B, C and D[]

European Union uses Annexes A, B, C and D instead of Appendixes 1, 2 and 3.

Annexes A, B and C are stricter versions of 1, 2 and 3 and contain more species that are protected under EU Internal Legislation.

Annex D, which doesn't have equivalent in CITES, is "monitoring list". It contains species, which import levels are monitored to determine the level of trade and any potential threat to species caused by trade.[19]

Amendments and reservations[]

Amendments to the Convention must be supported by a two-thirds majority who are "present and voting" and can be made during an extraordinary meeting of the COP if one-third of the Parties are interested in such a meeting. The Gaborone Amendment (1983) allows regional economic blocs to accede to the treaty. Reservations (Article XXIII) can be made by any Party with respect to any species, which considerably weakens the treaty (see Reservations entered by Parties CITES[20] for current reservations). Trade with non-Party states is allowed, although permits and certificates are recommended to be issued by exporters and sought by importers.

Notable reservations include those by Iceland, Japan and Norway on various baleen whale species and those on Falconiformes by Saudi Arabia.[21]

Shortcomings and concerns[]

Approach to biodiversity conservation[]

General limitations about the structure and philosophy of CITES include: by design and intent it focuses on trade at the species level and does not address habitat loss, ecosystem approaches to conservation, or poverty; it seeks to prevent unsustainable use rather than promote sustainable use (which generally conflicts with the Convention on Biological Diversity), although this has been changing (see Nile crocodile, African elephant, South African white rhino case studies in Hutton and Dickinson 2000). It does not explicitly address market demand.[22] In fact, CITES listings have been demonstrated to increase financial speculation in certain markets for high value species.[23][24][25] Funding does not provide for increased on-the-ground enforcement (it must apply for bilateral aid for most projects of this nature).

Drafting[]

By design, CITES regulates and monitors trade in the manner of a "" such that trade in all species is permitted and unregulated unless the species in question appears on the Appendices or looks very much like one of those taxa. Then and only then, trade is regulated or constrained. Because the remit of the Convention covers millions of species of plants and animals, and tens of thousands of these taxa are potentially of economic value, in practice this negative list approach effectively forces CITES signatories to expend limited resources on just a select few, leaving many species to be traded with neither constraint nor review. For example, recently several bird classified as threatened with extinction appeared in the legal wild bird trade because the CITES process never considered their status. If a "positive list" approach were taken, only species evaluated and approved for the positive list would be permitted in trade, thus lightening the review burden for member states and the Secretariat, and also preventing inadvertent legal trade threats to poorly known species.

Specific weaknesses in the text include: it does not stipulate guidelines for the 'non-detriment' finding required of national Scientific Authorities; non-detriment findings require copious amounts of information; the 'household effects' clause is often not rigid enough/specific enough to prevent CITES violations by means of this Article (VII); non-reporting from Parties means Secretariat monitoring is incomplete; and it has no capacity to address domestic trade in listed species.

Animal sourced pathogens[]

During the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 CEO Ivonne Higuero noted that illegal wildlife trade not only helps to destroy habitats, but these habitats create a safety barrier for humans that can prevent pathogens from animals passing themselves on to people.[26]

Reform suggestions[]

Suggestions for improvement in the operation of CITES include: more regular missions by the Secretariat (not reserved just for high-profile species); improvement of national legislation and enforcement; better reporting by Parties (and the consolidation of information from all sources-NGOs, TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring network and Parties); more emphasis on enforcement-including a technical committee enforcement officer; the development of CITES Action Plans (akin to Biodiversity Action Plans related to the Convention on Biological Diversity) including: designation of Scientific/Management Authorities and national enforcement strategies; incentives for reporting and timelines for both Action Plans and reporting. CITES would benefit from access to Global Environment Facility (GEF), funds-although this is difficult given the GEFs more ecosystem approach-or other more regular funds. Development of a future mechanism similar to that of the Montreal Protocol (developed nations contribute to a fund for developing nations) could allow more funds for non-Secretariat activities.[4]

On 15 July 2008, the Committee of Environmental Insecticides that oversees the administration of the convention between meetings of all the Parties granted China and Japan permission to import elephant ivory from four African government stockpiles, the ivory being sold at a single auction in each country. The amounts to be sold comprise approximately 44 tons from Botswana, 9 tons from Namibia, 51 tons from South Africa, and 4 tons from Zimbabwe. The Chinese government in 2003 acknowledged that it had lost track of 121 tons of ivory between 1991 and 2002.

TRAFFIC Data[]

From 2005 to 2009 the legal trade corresponded with these numbers

- 317,000 live birds

- More than 2 million live reptiles

- 2.5 million crocodile skins

- 2.1 million snake skins

- 73 tons of caviar

- 1.1 million beaver skins

- Millions of pieces of coral

- 20,000 mammalian hunting trophies

In the 1990s the annual trade of legal animal products was $160 billion annually. In 2009 the estimated value almost doubled to $300 billion.[27]

Additional information about the documented trade can be extracted through queries on the CITES website.

Meetings[]

The Conference of the Parties (CoP) is held once every three years. The last Conference of the Parties (CoP 18) was held in Geneva, Switzerland, 17–28 August 2019 and the one before it (CoP 17) was held in Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016. The next one (CoP 19) will be in San Jose, Cost Rica, in 2022. The location of the next CoP is chosen at the close of each CoP by a secret ballot vote.

The CITES Committees (Animals Committee, Plants Committee and Standing Committee) hold meetings during each year that does not have a CoP, while the Standing committee meets also in years with a CoP. The Committee meetings take place in Geneva, Switzerland (where the Secretariat of the CITES Convention is located), unless another country offers to host the meeting. The Secretariat is administered by UNEP. The Animals and Plants Committees have sometimes held joint meetings. The previous joint meeting was held in March 2012 in Dublin, Ireland, and the latest one was held in Veracruz, Mexico, in May 2014.

| Meeting | City | Country | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoP 1 | Bern | 2–6 November 1976 | |

| CoP 2 | San José | 19–30 March 1979 | |

| CoP 3 | New Delhi | 25 February – 8 March 1981 | |

| CoP 4 | Gaborone | 19 – 30 April 1983 | |

| CoP 5 | Buenos Aires | 22 April – 3 May 1985 | |

| CoP 6 | Ottawa | 12–24 July 1987 | |

| CoP 7 | Lausanne | 9–20 October 1989 | |

| CoP 8 | Kyoto | 2–13 March 1992 | |

| CoP 9 | Fort Lauderdale | 7–18 November 1994 | |

| CoP 10 | Harare | 9–20 June 1997 | |

| CoP 11 | Gigiri | 10–20 April 2000 | |

| CoP 12 | Santiago | 3–15 November 2002 | |

| CoP 13 | Bangkok | 2–14 October 2004 | |

| CoP 14 | The Hague | 3–15 June 2007 | |

| CoP 15 | Doha | 13–25 March 2010 | |

| CoP 16 | Bangkok | 3–14 March 2013 | |

| CoP 17 | Johannesburg | 24 September – 5 October 2016 | |

| CoP 18 | Geneva | 17–28 August 2019 | |

| CoP 19 | San José | 2022 |

A current list of upcoming meetings appears on the CITES calendar.[28]

See also[]

- Environmental agreements

- Illegal logging

- IUCN Red List

- Ivory trade

- Lacey Act

- List of species protected by CITES Appendix I

- List of species protected by CITES Appendix II

- List of species protected by CITES Appendix III

- Shark finning

- Wildlife conservation

- Wildlife Enforcement Monitoring System

- Wildlife management

- Wildlife smuggling

- World Wildlife Day

Footnotes[]

- ^ CITES treats the African forest elephant as a subspecies of L. africana and thus protected under Appendix I; most authorities now classify the forest elephant as a separate species, L. cyclotis.

References[]

- ^ "What is CITES?". cites.org. CITES. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Ivonne Higuero named as new CITES Secretary-General". cites.org. CITES. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Zimmerman, "The Black Market for Wildlife: llegal Wildlife Trade," Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 36 (5) 1657–1689 (November 2003)". Archived from the original on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Reeve, Policing International Trade in Endangered Species: The CITES Treaty and agreement. London: Earthscan, 2000.

- ^ "Countries currently subject to a recommendation to suspend trade". cites.org. CITES. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Bettina Wassener (12 March 2013). "No Species Is Safe From Burgeoning Wildlife Trade". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b CITES: Denmark. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ "List of Contracting Parties – CITES".

- ^ CITES: Faroe Islands. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ "Gaborone amendment to the text of the Convention". cites.org. CITES. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Gaborone amendment to the text of the Convention – CITES".

- ^ Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (2013). "Appendices I, II and III". Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. "The CITES Appendices". Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "CITES Calendar". cites.org. CITES. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Hutton and Dickinson, Endangered Species Threatened Convention: The Past, Present and Future of CITES. London: Africa Resources Trust, 2000.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Appendices I, II and III". cites.org. CITES. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "CITES Export Quotas". cites.org. CITES. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Article VII: Exemptions and Other Special Provisions Relating to Trade". Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. CITES. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Differences between regular CITES and EU's CITES https://ec.europa.eu/environment/cites/faq_en.htm#chapter3

- ^ "Reservations entered by Parties". www.cites.org.

- ^ "CITES Reservations Entered by Parties". cites.org. CITES. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Hill, 1990, "The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species: Fifteen Years Later," Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Journal 13: 231

- ^ van Uhm, D.P. The Illegal Wildlife Trade: Inside the World of Poachers, Smugglers and Traders (Studies of Organized Crime). New York: Springer.

- ^ Zhu, Annah (2020). "Restricting trade in endangered species can backfire, triggering market booms". The Conversation.

- ^ Zhu, Annah Lake (2 January 2020). "China's Rosewood Boom: A Cultural Fix to Capital Overaccumulation". Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 110 (1): 277–296. doi:10.1080/24694452.2019.1613955.

- ^ "Preventing illegal wildlife trade helps avoid zoonotic diseases". Balkan Green Energy News. 15 May 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, A. H.; Ehrlich, P. R. (2015). The Annihilation of Nature: Human Extinction of Birds and Mammals. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 150. ISBN 1421417189 – via Open Edition.

- ^ "CITES calendar". www.cites.org.

Further reading[]

- Oldfield, S. and McGough, N. (Comp.) 2007. A CITES manual for botanic gardens English version, Spanish version, Italian version Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI)

External links[]

| Wikidata has the property: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to CITES. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Member countries (Parties)

- Chronological list of Parties

- Alphabetical list of Parties at CITES and at the depositary

- National contacts

- Lists of species included in Appendices I, II and III (i.e. species protected by CITES)

- Environmental treaties

- Endangered species

- Treaties concluded in 1973

- Treaties entered into force in 1975

- Wildlife smuggling

- 1975 in the environment

- Treaties of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

- Treaties of Albania

- Treaties of Algeria

- Treaties of Angola

- Treaties of Antigua and Barbuda

- Treaties of Argentina

- Treaties of Armenia

- Treaties of Australia

- Treaties of Austria

- Treaties of Azerbaijan

- Treaties of the Bahamas

- Treaties of Bahrain

- Treaties of Bangladesh

- Treaties of Barbados

- Treaties of Belarus

- Treaties of Belgium

- Treaties of Belize

- Treaties of the People's Republic of Benin

- Treaties of Bhutan

- Treaties of Bolivia

- Treaties of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Treaties of Botswana

- Treaties of the military dictatorship in Brazil

- Treaties of Brunei

- Treaties of Bulgaria

- Treaties of Burkina Faso

- Treaties of Burundi

- Treaties of Cambodia

- Treaties of Cameroon

- Treaties of Canada

- Treaties of Cape Verde

- Treaties of the Central African Republic

- Treaties of Chad

- Treaties of Chile

- Treaties of the People's Republic of China

- Treaties of Colombia

- Treaties of the Comoros

- Treaties of the Republic of the Congo

- Treaties of Costa Rica

- Treaties of Ivory Coast

- Treaties of Croatia

- Treaties of Cuba

- Treaties of Cyprus

- Treaties of Czechoslovakia

- Treaties of the Czech Republic

- Treaties of Zaire

- Treaties of Denmark

- Treaties of Djibouti

- Treaties of Dominica

- Treaties of the Dominican Republic

- Treaties of Ecuador

- Treaties of Egypt

- Treaties of El Salvador

- Treaties of Equatorial Guinea

- Treaties of Eritrea

- Treaties of Estonia

- Treaties of the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

- Treaties of Fiji

- Treaties of Finland

- Treaties of France

- Treaties of Gabon

- Treaties of the Gambia

- Treaties of Georgia (country)

- Treaties of West Germany

- Treaties of East Germany

- Treaties of Ghana

- Treaties of Greece

- Treaties of Grenada

- Treaties of Guatemala

- Treaties of Guinea

- Treaties of Guinea-Bissau

- Treaties of Guyana

- Treaties of Honduras

- Treaties of the Hungarian People's Republic

- Treaties of Iceland

- Treaties of India

- Treaties of Indonesia

- Treaties of Pahlavi Iran

- Treaties of Iraq

- Treaties of Ireland

- Treaties of Israel

- Treaties of Italy

- Treaties of Jamaica

- Treaties of Japan

- Treaties of Jordan

- Treaties of Kazakhstan

- Treaties of Kenya

- Treaties of Kuwait

- Treaties of Kyrgyzstan

- Treaties of Laos

- Treaties of Latvia

- Treaties of Lebanon

- Treaties of Lesotho

- Treaties of Liberia

- Treaties of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya

- Treaties of Liechtenstein

- Treaties of Lithuania

- Treaties of Luxembourg

- Treaties of Madagascar

- Treaties of Malawi

- Treaties of Malaysia

- Treaties of the Maldives

- Treaties of Mali

- Treaties of Malta

- Treaties of Mauritania

- Treaties of Mauritius

- Treaties of Mexico

- Treaties of Monaco

- Treaties of Mongolia

- Treaties of Montenegro

- Treaties of Morocco

- Treaties of the People's Republic of Mozambique

- Treaties of Myanmar

- Treaties of Namibia

- Treaties of Nepal

- Treaties of the Netherlands

- Treaties of New Zealand

- Treaties of Nicaragua

- Treaties of Niger

- Treaties of Nigeria

- Treaties of Norway

- Treaties of Oman

- Treaties of Pakistan

- Treaties of Palau

- Treaties of Panama

- Treaties of Papua New Guinea

- Treaties of Paraguay

- Treaties of Peru

- Treaties of the Philippines

- Treaties of Poland

- Treaties of Portugal

- Treaties of Qatar

- Treaties of South Korea

- Treaties of Moldova

- Treaties of Romania

- Treaties of Russia

- Treaties of Rwanda

- Treaties of Samoa

- Treaties of San Marino

- Treaties of São Tomé and Príncipe

- Treaties of Saudi Arabia

- Treaties of Senegal

- Treaties of Serbia and Montenegro

- Treaties of Seychelles

- Treaties of Sierra Leone

- Treaties of Singapore

- Treaties of Slovakia

- Treaties of Slovenia

- Treaties of the Solomon Islands

- Treaties of the Somali Democratic Republic

- Treaties of South Africa

- Treaties of Spain

- Treaties of Sri Lanka

- Treaties of Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Treaties of Saint Lucia

- Treaties of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Treaties of the Democratic Republic of the Sudan

- Treaties of Suriname

- Treaties of Eswatini

- Treaties of Sweden

- Treaties of Switzerland

- Treaties of Syria

- Treaties of Tajikistan

- Treaties of Thailand

- Treaties of North Macedonia

- Treaties of Togo

- Treaties of Tonga

- Treaties of Trinidad and Tobago

- Treaties of Tunisia

- Treaties of Turkey

- Treaties of Uganda

- Treaties of Ukraine

- Treaties of the United Arab Emirates

- Treaties of the United Kingdom

- Treaties of Tanzania

- Treaties of the United States

- Treaties of Uruguay

- Treaties of Uzbekistan

- Treaties of Vanuatu

- Treaties of Venezuela

- Treaties of Vietnam

- Treaties of Yemen

- Treaties of Yugoslavia

- Treaties of Zambia

- Treaties of Zimbabwe

- Animal treaties

- Treaties extended to Aruba

- Treaties extended to the Netherlands Antilles

- Treaties extended to Greenland

- Treaties extended to Portuguese Macau

- Treaties extended to British Honduras

- Treaties extended to Bermuda

- Treaties extended to the British Indian Ocean Territory

- Treaties extended to the British Virgin Islands

- Treaties extended to the Cayman Islands

- Treaties extended to the Falkland Islands

- Treaties extended to Gibraltar

- Treaties extended to Guernsey

- Treaties extended to British Hong Kong

- Treaties extended to Jersey

- Treaties extended to the Gilbert and Ellice Islands

- Treaties extended to the Isle of Man

- Treaties extended to Montserrat

- Treaties extended to the Pitcairn Islands

- Treaties extended to Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

- Treaties entered into by the European Union

- CITES