Canopus, Egypt

ⲕⲁⲛⲱⲡⲟⲥ | |

| |

Shown within Egypt | |

| Alternative name | ⲕⲁⲛⲱⲡⲟⲥ |

|---|---|

| Location | Alexandria Governorate, Egypt |

| Region | Lower Egypt |

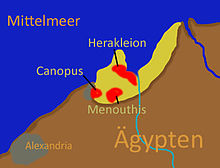

Canopus (Coptic: Ⲕⲁⲛⲱⲡⲟⲥ, Kanopos; Greek: Κανῶπος, Kanôpos), also known as Canobus (Greek: Κανῶβος, Kanôbos),[1] was an ancient Egyptian coastal town, located in the Nile Delta. Its site is in the eastern outskirts of modern-day Alexandria, around 25 kilometers (16 mi) from the center of that city. Canopus was located on the western bank at the mouth of the westernmost branch of the Delta – known as the Canopic or Heracleotic branch. It belonged to the seventh Egyptian Nome, known as Menelaites, and later as Canopites, after it. It was the principal port in Egypt for Greek trade before the foundation of Alexandria, along with Naucratis and Heracleion. Its ruins lie near the present Egyptian town of Abu Qir.

Land in the area of Canopus was subject to rising sea levels, earthquakes, tsunamis, and large parts of it seem to have succumbed to liquefaction sometime at the end of the 2nd century BC. The eastern suburbs of Canopus collapsed,[2] their remains being today submerged in the sea, with the western suburbs being buried beneath the modern coastal city of Abu Qir.

Name[]

| |||||

| pgwꜣt — Canopus (Decree of Canopus)[3] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: Ptolemaic dynasty (305–30 BC) | |||||

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

| ||||||||

| pngwꜣt — Canopus (Decree of Canopus)[4] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: Ptolemaic dynasty (305–30 BC) | ||||||||

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

| ||||||||

| prgwꜣt — Canopus (Decree of Canopus)[4] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: Ptolemaic dynasty (305–30 BC) | ||||||||

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

| |||

| Genp — Canopus[5] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

| |||||

| gꜣwtj — Canopus[6] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

The settlement's Egyptian name was written in Demotic as ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (pr-gwṱ, sometimes romanized Peguat or Pikuat).[7][8] The Greeks called it Canopus (Κάνωπος, Kánōpos) after a legendary commander of the era of the Trojan War supposedly buried there. The English form of the name derives from the Latinized form used under Roman rule.

(pr-gwṱ, sometimes romanized Peguat or Pikuat).[7][8] The Greeks called it Canopus (Κάνωπος, Kánōpos) after a legendary commander of the era of the Trojan War supposedly buried there. The English form of the name derives from the Latinized form used under Roman rule.

History[]

Ancient Egypt[]

Canopus was the site of a temple to the Egyptian god Serapis.[1]

The name of Canopus appears in the first half of the 6th century BC in a poem by Solon.[9] Early Egyptological excavations some 2 or 3 km from the area known today as Abu Qir have revealed extensive traces of the city with its quays, and granite monuments with the name of Ramesses II, but they may have been brought in for the adornment of the place at a later date. The exact date of the foundation of Canopus is unknown, but Herodotus refers to it as an ancient port. Homeric myth claims that it was founded by Menelaus, and named after Canopus, the pilot of his ship, who died there after being bitten by a serpent.[n 1] Legend describes how Menelaus built a monument to his memory on the shore, around which the town later grew up. There is unlikely to be any connection with "canopy". A temple to Osiris was built by king Ptolemy III Euergetes, but according to Herodotus, very near to Canopus was an older shrine,[n 2] a temple of Heracles that served as an asylum for fugitive slaves. Osiris was worshipped at Canopus under a peculiar form: that of a vase with a human head. Through an old misunderstanding, the name "canopic jars" was applied by early Egyptologists to the vases with human and animal heads in which the internal organs were placed by the Egyptians after embalming.

Hellenistic period[]

In Ptolemy III Euergetes' ninth regnal year (239 BC), a great assembly of priests at Canopus passed an honorific decree (the "Decree of Canopus") that, inter alia, conferred various new titles on the king and his consort, Berenice. Three examples of this decree are now known (plus some fragments), inscribed in Egyptian (in both hieroglyphic and demotic) and in classical Greek, and they were second only to the more famous Rosetta Stone in providing the key to deciphering the ancient Egyptian language. This was the earliest of the series of bilingual inscriptions of the "Rosetta Stone Series", also known as the Ptolemaic Decrees. There are three such Decrees altogether.[10]

The town had a large trade in henna.[1]

Roman period[]

In Roman times, the town was notorious for its dissoluteness.[1] Seneca wrote of the luxury and vice of Canopus, though he also mentioned that "Canopus does not keep any man from living simply".[11] Juvenal's Satire VI referred to the "debauchery" that prevailed there. The emperor Hadrian built a villa at Tivoli, 18 miles away from Rome, where he replicated for his enjoyment architectural patterns from all parts of the Roman Empire. One of these (and the most excavated and studied today) was borrowed from Canopus.[10]

Modern town[]

The Egyptian town of Abu Qir ("Father Cyrus"), honoring two Christian martyrs, is located a few kilometres away from the ruins of Canopus. It is a town (around 1900 with 1000 inhabitants), at the end of a little peninsula north-east of Alexandria. It has a trade in quails, which are caught in nets hung along the shore. Off Aboukir on 1 August 1798, the French Mediterranean fleet was destroyed within the roads by British Admiral Horatio Nelson. On 25 July 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte destroyed there a Turkish army 18,000 strong; and on 8 March 1801, the French garrison of 1,800 men was defeated by 20,000 English and Ottoman Turks commanded by Abercromby.[10]

See of Canopus[]

Egypt had many martyrs in the persecution of Diocletian, among others St. Athanasia with her three daughters, and St. Cyrus and John. There was here a monastery called Metanoia, founded by monks from Tabennisi, where many a patriarch of Alexandria took shelter during the religious quarrels of the 5th century. Three kilometres (2 mi) east of Canopus was the famous Pharaonic temple of Manouthin, afterwards destroyed by monks, and a church on the same spot dedicated to the Four Evangelists. St. Cyril of Alexandria solemnly transported the relics of the holy martyrs Cyrus and John into the church, which became an important place of pilgrimage. It was here that St. Sophronius of Jerusalem was healed of an ophthalmy that had been declared incurable by the physicians (610–619), whereupon he wrote the panegyric of the two saints with a compilation of seventy miracles worked in their sanctuary (Migne, Patrologia Graeca, LXXXVII, 3379-676) Canopus formed, with Menelaus and Schedia, a suffragan see subject to Alexandria in the Roman province of Aegyptus Prima; it is usually called Schedia in the Notitiae episcopatuum. Two titulars are mentioned by Lequien (II, 415), one in 325, the other in 362.[8]

Archaeology[]

Over time the land around Canopus was weakened by a combination of earthquakes, tsunamis and rising sea levels. Finds of pottery and coins appear to stop at the end of the 2nd century BC. At this point, probably after a severe flood, the eastern suburbs succumbed to liquefaction of the soil on which it was built. The hard clay turned rapidly into a liquid and the buildings collapsed.[2] The western suburbs eventually became the present day Egyptian coastal city of Abu Qir.

In 1933 ruins were sighted under the water by an RAF commander who was flying over Abu Qir Bay.[2] Egyptian scholar Prince Omar Toussoun[12] subsequently undertook archaeological investigations between 1934 and 1940. The undersea ruins were eventually identified as the lost cities of Heracleion and Canopus.

In 2000 the French underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio explored the submerged ruins of the two cities. Archaeological discoveries made by Goddio's team included parts of the "Naos of the Decades" temple and pieces of various statues, including a marble head of the god Serapis.[13]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ The first reference to Canopus as the helmsman of Menelaus seems to be by Hecataeus of Miletus.[citation needed]

- ^ This may have been a reference to the newly discovered Heracleion.[citation needed]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d EB (1878).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Shenker, Jack (15 Aug 2016). "Lost cities #6: how Thonis-Heracleion resurfaced after 1,000 years under water". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 Feb 2018.

- ^ Gauthier, Henri (1920). Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques Vol. 2. p. 154.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gauthier, Henri (1920). Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques Vol. 2. p. 49.

- ^ Budge, E. A. Wallis (1920). An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary: With an Index of English Words, King List and Geographical List with Indexes, List of Hieroglyphic Characters, Coptic and Semitic Alphabets, Volume 2. p. 1049.

- ^ Gauthier, Henri (1928). Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques Vol. 5. p. 211.

- ^ Erichsen, Wolja (1954). Demotisches Glossar. Copenhagen. p. 576.

- ^ Jump up to: a b CE (1913).

- ^ PDF file Research by Franck Goddio

- ^ Jump up to: a b c EB (1911).

- ^ Seneca. "Moral letters to Lucilius/Letter 51 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2021-09-10.

- ^ "Prince Omar Toussoun". In Magazine. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Goddio, Franck. "Sunken Civilizations". Frank Goddio, Underwater Archaeologist. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 23

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Vailhé, Siméon (1908). "Canopus". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company..

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Vailhé, Siméon (1908). "Canopus". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company..- Griffith, Francis Llewellyn (1911), , in Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 203

External links[]

- Archaeological sites in Egypt

- Mediterranean port cities and towns in Egypt

- Former populated places in Egypt

- Nile Delta

- Sunken cities