Chanson de geste

The chanson de geste[a] (Old French for 'song of heroic deeds', from Latin gesta 'deeds, actions accomplished')[1] is a medieval narrative, a type of epic poem that appears at the dawn of French literature.[2] The earliest known poems of this genre date from the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, shortly before the emergence of the lyric poetry of the troubadours and trouvères, and the earliest verse romances. They reached their highest point of acceptance in the period 1150–1250.[3]

Composed in verse, these narrative poems of moderate length (averaging 4000 lines[4]) were originally sung, or (later) recited, by minstrels or jongleurs. More than one hundred chansons de geste have survived in approximately three hundred manuscripts[5] that date from the 12th to the 15th century.

Origins[]

Since the 19th century, much critical debate has centered on the origins of the chansons de geste, and particularly on explaining the length of time between the composition of the chansons and the actual historical events which they reference.[6] The historical events the chansons allude to occur in the eighth through tenth centuries, yet the earliest chansons we have were probably composed at the end of the eleventh century: only three chansons de geste have a composition that incontestably dates from before 1150: the Chanson de Guillaume, The Song of Roland and Gormont et Isembart:[6] the first half of the Chanson de Guillaume may date from as early as the eleventh century;[7][8] Gormont et Isembart may date from as early as 1068, according to one expert;[9] and The Song of Roland probably dates from after 1086[10] to c.1100.[6][11]

Three early theories of the origin of chansons de geste believe in the continued existence of epic material (either as lyric poems, epic poems or prose narrations) in these intervening two or three centuries.[12] Critics like Claude Charles Fauriel, François Raynouard and German Romanticists like Jacob Grimm posited the spontaneous creation of lyric poems by the people as a whole at the time of the historic battles, which were later put together to form the epics.[13] This was the basis for the "cantilena" theory of epic origin, which was elaborated by Gaston Paris, although he maintained that single authors, rather than the multitude, were responsible for the songs.[14]

This theory was also supported by Robert Fawtier and by Léon Gautier (although Gautier thought the cantilenae were composed in Germanic languages).[14] At the end of the nineteenth century, Pio Rajna, seeing similarities between the chansons de geste and old Germanic/Merovingian tales, posited a Germanic origin for the French poems.[14] A different theory, introduced by the medievalist Paul Meyer, suggested the poems were based on old prose narrations of the original events.[12][15]

Another theory (largely discredited today[16]), developed by Joseph Bédier, posited that the early chansons were recent creations, not earlier than the year 1000, developed by singers who, emulating the songs of "saints lives" sung in front of churches (and collaborating with the church clerics[16]), created epic stories based on the heroes whose shrines and tombs dotted the great pilgrimage routes, as a way of drawing pilgrims to these churches.[17] Critics have also suggested that knowledge by clerics of ancient Latin epics may have played a role in their composition.[15][17]

Subsequent criticism has vacillated between "traditionalists" (chansons created as part of a popular tradition) and "individualists" (chansons created by a unique author),[15] but more recent historical research has done much to fill in gaps in the literary record and complicate the question of origins. Critics have discovered manuscripts, texts and other traces of the legendary heroes, and further explored the continued existence of a Latin literary tradition (c.f. the scholarship of Ernst Robert Curtius) in the intervening centuries.[18] The work of Jean Rychner on the art of the minstrels[16] and the work of Parry and Lord on Yugoslavian oral traditional poetry, Homeric verse and oral composition have also been suggested to shed light on the oral composition of the chansons, although this view is not without its critics[19] who maintain the importance of writing not only in the preservation of the texts, but also in their composition, especially for the more sophisticated poems.[19]

Subject matter and structure[]

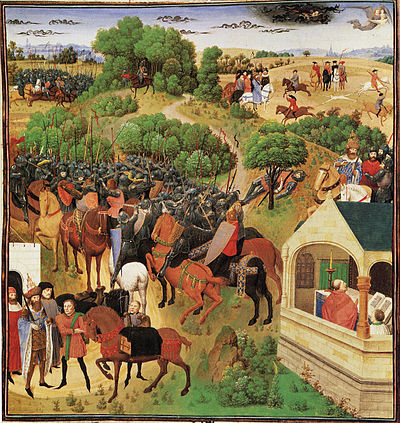

Composed in Old French and apparently intended for oral performance by jongleurs, the chansons de geste narrate legendary incidents (sometimes based on real events) in the history of France during the eighth, ninth and tenth centuries, the age of Charles Martel, Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, with emphasis on their conflicts with the Moors and Saracens, and also disputes between kings and their vassals.

The traditional subject matter of the chansons de geste became known as the Matter of France. This distinguished them from romances concerned with the Matter of Britain, that is, King Arthur and his knights; and with the so-called Matter of Rome, covering the Trojan War, the conquests of Alexander the Great, the life of Julius Cæsar and some of his Imperial successors, who were given medieval makeovers as exemplars of chivalry.[20]

A key theme of the chansons de geste, which set them off from the romances (which tended to explore the role of the "individual"), is their critique and celebration of community/collectivity (their epic heroes are portrayed as figures in the destiny of the nation and Christianity)[21] and their representation of the complexities of feudal relations and service.

The subject matter of the chansons evolved over time, according to public taste. Alongside the great battles and scenes of historic prowess of the early chansons there began to appear other themes. Realistic elements (money, urban scenes) and elements from the new court culture (female characters, the role of love) began to appear.[3] Other fantasy and adventure elements, derived from the romances, were gradually added:[3] giants, magic, and monsters increasingly appear among the foes along with Muslims. There is also an increasing dose of Eastern adventure, drawing on contemporary experiences in the Crusades; in addition, one series of chansons retells the events of the First Crusade and the first years of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The conflicts of the 14th century (Hundred Years' War) brought a renewed epic spirit and nationalistic (or propagandistic[22]) fervor to some chansons de geste (such as La Chanson de Hugues Capet).[23]

The poems contain an assortment of character types; the repertoire of valiant hero, brave traitor, shifty or cowardly traitor, Saracen giant, beautiful Saracen princess, and so forth. As the genre matured, fantasy elements were introduced. Some of the characters that were devised by the poets in this genre include the fairy Oberon, who made his literary debut in Huon de Bordeaux; and the magic horse Bayard, who first appears in Renaud de Montauban. Quite soon an element of self-parody appears; even the august Charlemagne was not above gentle mockery in the Pèlerinage de Charlemagne.

The narrative structure of the chanson de geste has been compared to the one in the Nibelungenlied and in creole legends by Henri Wittmann[24] on the basis of common narreme structure as first developed in the work of [25] and [26]

Versification[]

Early chansons de geste were typically composed in ten-syllable lines grouped in assonanced (meaning that the last stressed vowel is the same in each line throughout the stanza, but the last consonant differs from line to line) stanzas (called laisses). These stanzas are of variable length.

An example from the Chanson de Roland illustrates the technique of the ten-syllable assonanced form. The assonance in this stanza is on e:

Desuz un pin, delez un eglanter |

Under a pine tree, by a rosebush, |

Later chansons were composed in monorhyme stanzas, in which the last syllable of each line rhymes fully throughout the stanza. Later chansons also tended to be composed using alexandrines (twelve-syllable) lines, instead of ten-syllable lines (some early chansons, such as Girart de Vienne, were even adapted into a twelve-syllable version).

The following example of the twelve-syllable rhymed form is from the opening lines of , a chanson in the Crusade cycle. The rhyme is on ie:

Or s'en fuit Corbarans tos les plains de Surie, |

So Corbaran escaped across the plains of Syria; |

These forms of versification were substantially different than the forms found in the Old French verse romances (romans) which were written in octosyllabic rhymed couplets.

Composition and performance[]

The public of the chansons de geste—the lay (secular) public of the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries—was largely illiterate,[27] except for (at least to the end of the 12th century) members of the great courts and (in the south) smaller noble families.[28] Thus, the chansons were primarily an oral medium.

Opinions vary greatly on whether the early chansons were first written down and then read from manuscripts (although parchment was quite expensive[29]) or memorized for performance,[30] or whether portions were improvised,[29] or whether they were entirely the product of spontaneous oral composition and later written down. Similarly, scholars differ greatly on the social condition and literacy of the poets themselves; were they cultured clerics or illiterate jongleurs working within an oral tradition? As an indication of the role played by orality in the tradition of the chanson de geste, lines and sometimes whole stanzas, especially in the earlier examples, are noticeably formulaic in nature, making it possible both for the poet to construct a poem in performance and for the audience to grasp a new theme with ease.

Scholarly opinions differ on the exact manner of recitation, but it is generally believed that the chansons de geste were originally sung (whereas the medieval romances were probably spoken)[30] by poets, minstrels or jongleurs, who would sometimes accompany themselves, or be accompanied, on the vielle, a mediæval fiddle played with a bow. Several manuscript texts include lines in which the jongleur demands attention, threatens to stop singing, promises to continue the next day, and asks for money or gifts.[29] By the middle of the 13th century, singing had probably given way to recitation.[3]

It has been calculated that a reciter could sing about a thousand verses an hour[31] and probably limited himself to 1000–1300 verses by performance,[27] making it likely that the performance of works extended over several days.[31] Given that many chansons from the late twelfth century on extended to over 10,000 verses or more (for example, Aspremont comprises 11,376 verses, while Quatre Fils Aymon comprises 18,489 verses), it is conceivable that few spectators heard the longest works in their entirety.[32]

While poems like The Song of Roland were sometimes heard in public squares and were no doubt warmly received by a broad public,[33] some critics caution that the chansons should probably not be characterized as popular literature[34] and some chansons appear particularly tailored for an audience of aristocratic, privileged or warrior classes.[35]

The poems themselves[]

More than one hundred chansons de geste have survived in around three hundred manuscripts[5] that date from the 12th to the 15th century. Several popular chansons were written down more than once in varying forms. The earliest chansons are all (more or less) anonymous; many later ones have named authors.

By the middle of the 12th century, the corpus of works was being expanded principally by "cyclisation", that is to say by the formation of "cycles" of chansons attached to a character or group of characters—with new chansons being added to the ensemble by singing of the earlier or later adventures of the hero, of his youthful exploits ("enfances"), the great deeds of his ancestors or descendants, or his retreat from the world to a convent ("moniage") – or attached to an event (like the Crusades).[36]

About 1215 Bertrand de Bar-sur-Aube, in the introductory lines to his Girart de Vienne, subdivided the Matter of France, the usual subject area of the chansons de geste, into three cycles, which revolved around three main characters (see quotation at Matter of France). There are several other less formal lists of chansons, or of the legends they incorporate. One can be found in the fabliau entitled Des Deux Bordeors Ribauz, a humorous tale of the second half of the 13th century, in which a jongleur lists the stories he knows.[37] Another is included by the Catalan troubadour Guiraut de Cabrera in his humorous poem Ensenhamen, better known from its first words as "Cabra juglar": this is addressed to a juglar (jongleur) and purports to instruct him on the poems he ought to know but doesn't.[38]

The listing below is arranged according to Bertrand de Bar-sur-Aube's cycles, extended with two additional groupings and with a final list of chansons that fit into no cycle. There are numerous differences of opinion about the categorization of individual chansons.

Geste du roi[]

The chief character is usually Charlemagne or one of his immediate successors. A pervasive theme is the King's role as champion of Christianity. This cycle contains the first of the chansons to be written down, the Chanson de Roland or "The Song of Roland".

- Chanson de Roland (c. 1100 for the Oxford text, the earliest written version); several other versions exist, including the Occitan [39], the Middle High German and the Latin Carmen de Prodicione Guenonis.

- Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne or Voyage de Charlemagne à Jérusalem et à Constantinople dealing with a fictional expedition by Charlemagne and his knights (c. 1140; two 15th century reworkings)

- Fierabras (c. 1170)[40][41]

- Aspremont (c. 1190); a later version formed the basis of Aspramonte by Andrea da Barberino

- Anseïs de Carthage (c. 1200)

- Chanson de Saisnes or "Song of the Saxons", by Jean Bodel (c. 1200)

- Huon de Bordeaux originally c. 1215–1240, known from slightly later manuscripts. A "prequel" and four sequels were later added:

- Chanson d'Esclarmonde

- Clarisse et Florent

- Yde et Olive

- (c. 1230)[42]

- (before 1239)[43]

- by Adenet le Roi (c. 1275), and a later Franco-Italian reworking

- Les Enfances Ogier by Adenet le Roi (c. 1275) | to Ogier the Dane.

- Entrée d'Espagne (c. 1320)[44]

- (c. 1360)

- Galiens li Restorés known from a single manuscript of about 1490[45]

- Aiquin or Acquin[46]

- or Otinel

- Basin

- Ogier le Danois by Raimbert de Paris[47]

- [48]

- Macaire or La Chanson de la Reine Sebile

- Huon d'Auvergne, a lost chanson known from a 16th-century retelling. The hero is mentioned among epic heroes in the Ensenhamen of Guiraut de Cabrera, and figures as a character in Mainet

Geste de Garin de Monglane[]

The central character is not Garin de Monglane but his supposed great-grandson, Guillaume d'Orange. These chansons deal with knights who were typically younger sons, not heirs, who seek land and glory through combat with the Infidel (in practice, Muslim) enemy.

- Chanson de Guillaume (c. 1100)

- Couronnement de Louis (c. 1130)

- Le Charroi de Nîmes (c. 1140)

- La Prise d'Orange (c. 1150), reworking of a lost version from before 1122

- Aliscans (c. 1180), with several later versions

- by (fl. 1170)

- by (fl. 1170)

- , by Herbert le Duc of Dammartin (fl. 1170)

- or "Simon of Apulia", fictional eastern adventures; the hero is said to be a grandson of Garin de Monglane[49]

- (late 12th); the hero is a son of Merovingian King Clovis I

- Aymeri de Narbonne by Bertrand de Bar-sur-Aube (late 12th/early 13th)

- Girart de Vienne by Bertrand de Bar-sur-Aube (late 12th/early 13th); also found in a later shorter version alongside Hernaut de Beaulande and Renier de Gennes[50]

- (15th century)

- Garin de Monglane (13th century)

- ; a fragment of the 14th century and a later version[50]

- [50]

- (before 1250)

- Les Narbonnais (c. 1205), in two parts, known as Le département des enfants Aymeri, Le siège de Narbonne

- Les Enfances Vivien (c. 1205)[51]

- or La Chevalerie Vivien

- (c. 1180)

- (c. 1275), reworking by Adenet le Roi of the Siege de Barbastre

- (13th century)

- (13th century)

- La Mort Aymeri de Narbonne (c. 1180)

- (1160–1180)[52]

Geste de Doon de Mayence[]

This cycle concerns traitors and rebels against royal authority. In each case the revolt ends with the defeat of the rebels and their eventual repentance.

- Gormond et Isembart

- Girart de Roussillon (1160–1170). The hero Girart de Roussillon also figures in Girart de Vienne, in which he is identified as a son of Garin de Monglane. There is a later sequel:

- Renaud de Montauban or Les Quatre Fils Aymon (end of the 12th century)

- Raoul de Cambrai, apparently begun by Bertholais; existing version from end of 12th century

- Doön de Mayence (mid 13th century)

- current in the second half of the 12th century, now known only in fragments which derive from a 13th-century version.[53] To this several sequels were attached:

- , probably composed between 1195 and 1205. The fictional heroine is first married to Garnier de Nanteuil, who is son of Doon de Nanteuil and grandson of Doon de Mayence. After Garnier's death she marries the Saracen Ganor

- , evidently popular around 1207 when the troubadour Raimbaut de Vaqueiras mentions the story. The fictional hero is son of the heroine of Aye d'Avignon (to which Gui de Nanteuil forms a sequel)

- . The fictional hero is son of the hero of Gui de Nanteuil

- . The fictional heroine is daughter of the heroine of Aye d'Avignon. Exiled from France, she gives birth to a son, Hugues, who becomes king of Hungary[54]

- Maugis d'Aigremont

- Vivien l'Amachour de Monbranc

Lorraine cycle[]

This local cycle of epics of Lorraine traditional history, in the late form in which it is now known, includes details evidently drawn from Huon de Bordeaux and Ogier le Danois.

Crusade cycle[]

Not listed by Bertrand de Bar-sur-Aube, this cycle deals with the First Crusade and its immediate aftermath.

- Chanson d'Antioche, apparently begun by Richard le Pèlerin c. 1100; earliest surviving text by c. 1180; expanded version 14th century

- telling the adventures (mostly fictional) of the poor crusaders led by Peter the Hermit; the hero is Harpin de Bourges. The episode was eventually incorporated, c. 1180, by Graindor de Douai in his reworking of the Chanson d'Antioche

- tells the story of old Matabrune and of the great-grandfather of Godefroi de Bouillon

- tells the story of Elias, grandfather of Godefroi de Bouillon. Originally composed around 1192, it was afterwards extended and divided into several branches

- or "Childhood exploits of Godefroi" tells the story of the youth of Godefroi de Bouillon and his three brothers

- Chanson de Jérusalem

- , quite unhistorical, narrates Godefroi's poisoning by the Patriarch of Jerusalem

- Baudouin de Sebourc (mid-14th century)

- (early 14th century)

Others[]

- Gormont et Isembart[55]

- Ami et Amile, followed by a sequel:

- Jourdain de Blaye

- Beuve de Hanstonne, and a related poem:

- Daurel et Beton, whose putative Old French version is lost; the story is known from an Occitan version of c. 1200

- Aigar et Maurin

- , a lost chanson[56]

- Aiol (13th century)[57]

- , possibly a romance

The chansons de geste reached their apogee in the period 1150–1250.[3] By the middle of the 13th century, public taste in France had begun to abandon these epics, preferring, rather, the romances.[58] As the genre progressed in the middle of the 13th century, only certain traits (like versification, laisse structure, formulaic forms, setting, and other clichés of the genre) remained to set the chansons apart from the romances.[58] The 15th century saw the cycles of chansons (along with other chronicles) converted into large prose compilations (such as the compilation made by David Aubert).[23][59] Yet, the themes of the epics continued to exert an influence through the 16th century.[59]

Legacy and adaptations[]

The chansons de geste created a body of mythology that lived on well after they ceased to be produced in France.

The French chanson gave rise to the Old Spanish tradition of the cantar de gesta.

The chanson de geste was also adapted in southern (Occitan-speaking) France. One of the three surviving manuscripts of the chanson Girart de Roussillon (12th century) is in Occitan,[60] as are two works based on the story of Charlemagne and Roland, [61] and (early 12th century).[62] The chanson de geste form was also used in such Occitan texts as Canso d'Antioca (late 12th century), Daurel e Betó (first half of the 13th century), and Song of the Albigensian Crusade (c.1275) (cf Occitan literature).

In medieval Germany, the chansons de geste elicited little interest from the German courtly audience, unlike the romances which were much appreciated. While The Song of Roland was among the first French epics to be translated into German (by Konrad der Pfaffe as the Rolandslied, c.1170), and the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach based his (incomplete) 13th century epic Willehalm (consisting of seventy-eight manuscripts) on the Aliscans, a work in the cycle of William of Orange (Eschenbach's work had a great success in Germany), these remained isolated examples. Other than a few other works translated from the cycle of Charlemagne in the 13th century, the chansons de geste were not adapted into German, and it is believed that this was because the epic poems lacked what the romances specialized in portraying: scenes of idealized knighthood, love and courtly society.[63]

In the late 13th century, certain French chansons de geste were adapted into the Old Norse Karlamagnús saga.

In Italy, there exist several 14th-century texts in verse or prose which recount the feats of Charlemagne in Spain, including a chanson de geste in Franco-Venetian, the Entrée d'Espagne (c.1320)[64] (notable for transforming the character of Roland into a knight errant, similar to heroes from the Arthurian romances[65]), and a similar Italian epic La Spagna (1350–1360) in ottava rima. Through such works, the "Matter of France" became an important source of material (albeit significantly transformed) in Italian romantic epics. Morgante (c.1483) by Luigi Pulci, Orlando innamorato (1495) by Matteo Maria Boiardo, Orlando furioso (1516) by Ludovico Ariosto, and Jerusalem Delivered (1581) by Torquato Tasso are all indebted to the French narrative material (the Pulci, Boiardo and Ariosto poems are founded on the legends of the paladins of Charlemagne, and particularly, of Roland, translated as "Orlando").

The incidents and plot devices of the Italian epics later became central to works of English literature such as Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene; Spenser attempted to adapt the form devised to tell the tale of the triumph of Christianity over Islam to tell instead of the triumph of Protestantism over Roman Catholicism.

The Welsh poet, painter, soldier and engraver David Jones's Modernist poem In Parenthesis was described by contemporary critic Herbert Read as having "the heroic ring which we associate with the old chansons de geste".

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Crosland, 1.

- ^ France, Peter (1995). The new Oxford companion to literature in French. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198661258.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Hasenohr, 242.

- ^ Holmes, 66.

- ^ Jump up to: a b La Chanson de Roland, 12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hasenohr, 239.

- ^ Hasenohr, 520–522.

- ^ Holmes, 102–104.

- ^ Holmes, 90–92.

- ^ La Chanson de Roland, 10.

- ^ Hasenohr, 1300.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holmes, 68.

- ^ Holmes, 66–67.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Holmes, 67.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c see also Hasenohr, 239.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c La Chanson de Roland, 11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holmes, 68-9.

- ^ see also Hasenohr, 240.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hasenohr, 240.

- ^ This three-way classification of mythology is set out by the twelfth-century poet Jean Bodel in the Chanson de Saisnes: for details see Matter of France.

- ^ La Chanson de Roland, 16–17.

- ^ Hasenohr, 242

- ^ Jump up to: a b Adam, 45.

- ^ Wittmann, Henri. 1995. "La structure de base de la syntaxe narrative dans les contes et légendes du créole haïtien." Poétiques et imaginaires: francopolyphonie littéraire des Amériques. Edited by Pierre Laurette & Hans-George Ruprecht. Paris: L'Harmattan, pp. 207–218.[1]

- ^ Dorfman, Eugène. 1969. The narreme in the medieval romance epic: An introduction to narrative structures. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- ^ *Tusseau, Jean-Pierre & Henri Wittmann. 1975. "Règles de narration dans les chansons de geste et le roman courtois". Folia linguistica 7.401-12.[2]

- ^ Jump up to: a b La Chanson de Roland, 12.

- ^ Bumke, 429.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c La Chanson de Roland, 14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bumke, 521-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bumke, 522.

- ^ see Bumke, 522.

- ^ Brault, 28.

- ^ Brault, 353 (note 166).

- ^ see Brault, 28.

- ^ Adam, 10.

- ^ Recueil général et complet des fabliaux ed. A. de Montaiglon (1872) vol. 1 p. 3

- ^ Martín de Riquer, Los cantares de gesta franceses (1952) pp. 390–404

- ^ Le Roland occitan ed. and tr. Gérard Gouiran, Robert Lafont (1991)

- ^ La geste de Fierabras, le jeu du réel et de l'invraissemblable ed. André de Mandach. Geneva, 1987.

- ^ "Fierabras and Floripas: A French Epic Allegory" ed. and trans. by Michael A.H. Newth. New York: Italica Press, 2010.

- ^ Ed. F. Guessard, S. Luce. Paris: Vieweg, 1862.

- ^ Jehan de Lanson, chanson de geste of the 13th Century ed. J. Vernon Myers. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1965.

- ^ Ed. A. Thomas. Paris: Société des anciens textes français, 1913.

- ^ Galiens li Restorés ed. Edmund Stengel (1890); Le Galien de Cheltenham ed. D. M. Dougherty, E. B. Barnes. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1981.

- ^ Aiquin ou la conquête de la Bretagne par le roi Charlemagne ed. F. Jacques. Aix-en-Provence: Publications du CUER MA, 1977.

- ^ Raimbert de Paris, La Chevalerie Ogier de Danemarche ed. J. Barrois (1842)

- ^ Ed. François Guessard, Henri Michelant. Paris, 1859.

- ^ Simon de Pouille ed. Jeanne Baroin (1968)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c La geste de Beaulande ed. David M. Dougherty, E. B. Barnes (1966)

- ^ Ed. C. Wahlund, H. von Feilitzen. Upsala and Paris, 1895.

- ^ Ed. W. Cloetta. Paris, 1906–13.

- ^ "La chanson de Doon de Nanteuil: fragments inédits" ed. Paul Meyer in Romania vol. 13 (1884)

- ^ Parise la Duchesse ed. G. F. de Martonne (1836); Parise la Duchesse ed. F. Guessard, L. Larchey (1860)

- ^ Gormont et Isembart ed. Alphonse Bayot (1931)

- ^ R. Weeks, "Aïmer le chétif" in PMLA vol. 17 (1902) pp. 411–434.

- ^ Ed. Jacques Normand and Gaston Raynaud. Paris, 1877.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Adam, 38.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Haseonohr, 243.

- ^ Hasenohr, 547.

- ^ Hasenohr, 1305.

- ^ Hasenohr, 1320.

- ^ Bumke, 92–93.

- ^ Hasenohr. Article: "Entrée d'Espagne", pp. 412–3.

- ^ Brand, 168.

Footnotes[]

References[]

- (in French) Antoine Adam, Georges Lerminier, and Édouard Morot-Sir, eds. Littérature française. "Tome 1: Des origines à la fin du XVIIIe siècle," Paris: Larousse, 1967.

- Peter Brand and Lino Pertile, eds. The Cambridge History of Italian Literature Cambridge. 1996; revised edition: 1999. ISBN 0-521-66622-8

- Gerard J. Brault. The Song of Roland: An Analytical Edition. Tome I: Introduction and Commentary. Pennsylvania State University, 1978. ISBN 0-271-00516-5

- Joachim Bumke. Courtly Culture: Literature and Society in the High Middle Ages. English translation: 1991. The Overlook Press: New York, 2000. ISBN 1-58567-051-0

- Jessie Crosland. The Old French Epic. New York: Haskell House, 1951.

- (in French) Geneviève Hasenohr and Michel Zink, eds. Dictionnaire des lettres françaises: Le Moyen Age. Collection: La Pochothèque. Paris: Fayard, 1992. ISBN 2-253-05662-6

- Urban T. Holmes Jr. A History of Old French Literature from the Origins to 1300. New York: F.S. Crofts, 1938.

- (in French) La Chanson de Roland. Edited and Translated into Modern French by Ian Short. Paris: Livre de Poche, 1990. p. 12. ISBN 978-2-253-05341-5

External links[]

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Chansons de Geste. |

- La Chanson de Geste, with useful references (in French)

- Chansons de geste

- French folklore

- French mythology

- Matter of France

- Medieval legends

- Medieval literature

- Medieval French literature

- Epic poetry

- Old French texts

- Walloon culture