Chevy Chase, Maryland

Chevy Chase, Maryland | |

|---|---|

Unincorporated community | |

4-H Youth Conference Center | |

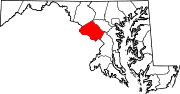

Chevy Chase Location of Chevy Chase in the U.S. state of Maryland | |

| Coordinates: 38°58′16″N 77°04′35″W / 38.97111°N 77.07639°WCoordinates: 38°58′16″N 77°04′35″W / 38.97111°N 77.07639°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

Chevy Chase is the name of both a town and an unincorporated census-designated place (Chevy Chase (CDP), Maryland) that straddle the northwest border of Washington, D.C. and Montgomery County, Maryland, United States. Several settlements in the same area of Montgomery County and one neighborhood of Washington include Chevy Chase in their names. These villages, the town, and the CDP share a common history and together form a larger community colloquially referred to as Chevy Chase.

Primarily a residential suburb, Chevy Chase adjoins Friendship Heights, a popular shopping district. It includes the National 4-H Youth Conference Center, which hosts the National 4-H Conference, an event for 4-Hers throughout the nation to attend, and the National Science Bowl annually in either late April or early May.[1] Chevy Chase is also the home of the Chevy Chase Club and Columbia Country Club, private clubs whose members include many prominent politicians and Washingtonians.[2]

Chevy Chase was noted as "the most educated town in America" in a study conducted by the Stanford Graduate School of Education, with 93.5 percent of adult residents having at least a bachelor's degree.[3]

The name Chevy Chase is derived from Cheivy Chace, the name of the land patented to Colonel Joseph Belt from Charles Calvert, 5th Baron Baltimore on July 10, 1725. It has historic associations with a 1388 chevauchée — a French word describing a border raid — fought by Lord Percy of England and Earl Douglas of Scotland over hunting grounds, or a "chace", in the Cheviot Hills of Northumberland and Otterburn.[4] The battle was memorialized in "The Ballad of Chevy Chase".

History[]

19th Century[]

In the 1880s, Senator Francis G. Newlands of Nevada and his partners began acquiring farmland in this unincorporated area of Maryland and just inside the District of Columbia, for the purpose of developing a residential streetcar suburb for Washington, D.C., during the expansion of the Washington streetcars system. Newlands and his partners founded The Chevy Chase Land Company in 1890, and its holdings of more than 1,700 acres (6.9 km2) eventually extended along the present-day Connecticut Avenue from Florida Avenue north to Jones Bridge Road. The Chevy Chase Land Company built houses for $5,000 and up on Connecticut Avenue and $3,000 and up on side streets.[5] The company banned commerce from the residential neighborhoods.[6] The streetcar soon became vital to the community; it connected workers to the city, and even ran errands for residents. Toward the northern end of its holdings, the Land Company formed a manmade lake, called Chevy Chase Lake, to service a local hydroelectric power plant, and provide a venue for boating, swimming, and other activities.[7]

Leon E. Dessez was Chevy Chase's first resident. He and Lindley Johnson of Philadelphia designed the first four houses in the area.[8]

Part of the original Cheivy Chace patent had been sold to Abraham Bradley, who built an estate known as the Bradley Farm.[9] In 1892, Newlands and other members of the Metropolitan Club of Washington, D.C., founded a hunt club called Chevy Chase Hunt, which would later become Chevy Chase Club. In 1894, the club located itself on the former Bradley Farm property under a lease from its owners. The club introduced a six-hole golf course to its members in 1895, and purchased the 9.36-acre Bradley Farm tract in 1897.[10][9][11]

20th Century[]

Lea M. Bouligny founded the Chevy Chase College and Seminary for Young Ladies at the Chevy Chase Inn, located at 7100 Connecticut Avenue). The name was changed to Chevy Chase Junior College in 1927. The National 4-H Club Foundation purchased the property in 1951.[12]

During the first half of the 20th century, Chevy Chase was a sundown town that excluded individuals based on race and religion[citation needed]. Founder Francis G. Newlands was an "avowed racist"[13] who in 1912 introduced a plank to the Democratic Convention that called for a constitutional amendment to disenfranchise black men and limit immigration to whites only. In 1906, the Chevy Chase Land Company had blocked the development of land it had assembled, known as Belmont, after they learned its Black developers were selling house lots to other African Americans. In subsequent litigation, the company and its affiliates argued that those developers had committed fraud by proposing "to sell lots...to negroes."[13]

By the 1920s, restrictive covenants were added to Chevy Chase real estate deeds. Some prohibited both the sale or rental of homes to "a Negro or one of the African race." Others prohibited sales or rentals to "any persons of the Semetic [sic] race", i.e. the exclusion of Jews.[13] By World War II, such restrictive language had largely disappeared from real estate transactions, and all were voided by the 1948 Supreme Court decision in Shelley v. Kraemer.

Subdivisions[]

- Census-designated place of Chevy Chase

- Incorporated town of Chevy Chase

- Chevy Chase (Washington, D.C.)

Villages[]

- Chevy Chase Village, Maryland

- Chevy Chase Section Three, Maryland

- Chevy Chase Section Five, Maryland

- Martin's Additions, Maryland

- North Chevy Chase, Maryland

In addition to the Maryland villages listed above, the United States Postal Service uses Chevy Chase for some postal addresses that lie lie outside historical Chevy Chase: in Somerset, the Village of Friendship Heights, and the part of Silver Spring east of Jones Mill Road and Beach Drive and west of Grubb Road.

Education[]

Chevy Chase is served by the Montgomery County Public Schools. Private schools in Chevy Chase include Concord Hill School and Oneness-Family School. Residents of Chevy Chase are zoned to either Chevy Chase or North Chevy Chase elementary, Silver Creek Middle School, and Bethesda-Chevy Chase High-school.

Retail[]

Wisconsin Avenue in Friendship Heights was, until 2020, the only concentration of traditional department stores in D.C.:[14]

- Neiman Marcus (closed in 2020), part of the Mazza Gallerie shopping center

- Lord & Taylor (in D.C.), which as of late 2020 was to go out of business

On the Maryland side, two department stores will remain:

- Saks Fifth Avenue, freestanding building which together with another complex of shots called The Collection at Chevy Chase with luxury boutiques such as Tiffany & Co.

- Bloomingdale's, part of Wisconsin Place, with residential and office space, a Whole Foods Market and boutiques

All are within walking distance of each other, as are these other centers in D.C.:

- Chevy Chase Pavilion, which was anchored by a Cost Plus World Market and Old Navy which both closed in 2020.[15]

- Friendship Center, with big box discount retailers Marshalls and DSW

- Chevy Chase Metro Center, with box box craft retailer Michaels

Notable people[]

Current residents[]

- Ann Brashares - author[16]

- Tony Kornheiser - television host, currently ESPN employee presenter

- Brett Kavanaugh - Associate Justice, United States Supreme Court

- Marvin Kalb - journalist[16]

- Ted Lerner - owner of Lerner Enterprises and the Washington Nationals

- Chris Matthews - commentator

- Krzysztof Pietroszek - professor and filmmaker

- Jerome Powell - current Chairman of the Federal Reserve

- John Roberts - Chief Justice, United States Supreme Court[16]

- Mark Shields - political columnist[16]

- George Will - conservative commentator[16]

- A.B. Stoddard - Political commentator and editor of RealClearPolitics

- Howard Kurtz - Host of Fox News program Media Buzz

- Collin Martin - Soccer Player

Former residents[]

- Richard Helms - former Director of the Central Intelligence Agency

- Tom Braden - journalist and author[17]

- David Brinkley - journalist[17]

- John Charles Daly - radio and television personality

- Bill Guckeyson - athlete and military aviator

- Genevieve Hughes - one of the 13 original Freedom Riders[18]

- Hubert Humphrey - Vice President of the United States under Lyndon Johnson[17]

- Gayle King - Co-anchor of CBS This Morning and an editor-at-large for O, The Oprah Magazine

- Sandra Day O'Connor - United States Supreme Court Justice; lived in Chevy Chase until 2005[17]

- Hilary Rhoda - model[19]

- Nancy Grace Roman - NASA's first female executive and, as Chief of Astronomy throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the founder of its space astronomy program and "Mother of Hubble".

- Peter Rosenberg - Radio disc jockey, television host, and podcaster[20]

- Danny Rubin - American-Israeli basketball player for Bnei Herzliya of the Israeli Basketball Premier League[21]

- Ed Henry - White House correspondent for Fox News.

- Anthony McAuliffe - US General known for his defense of Bastogne during World War II.

- Jamshid Amouzegar, former prime minister of Iran.

References[]

- ^ "U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy, National Science Bowl®". United States Department of Energy.

- ^ "Obama to Join Maryland Country Club". Washingtonian. 2017-10-06. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ^ "Affluent Md. suburb named nation's most educated". WTOP. 2015-01-07. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ^ "The Naming of Chevy Chase". Chevy Chase Historical Society.

- ^ Ohmann, Richard Malin (1996). Selling Culture: Magazines, Markets, and Class at the Turn of the Century. Verso.

- ^ Dryden, Steve (1999). "The History of Chevy Chase and Friendship Heights". Bethesda Magazine.

- ^ "The History of Chevy Chase and Friendship Heights". Bethesda Magazine. September 27, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ Benedetto, Robert; Donovan, Jane; Vall, Kathleen Du (2003). Historical Dictionary of Washington. Scarecrow Press. p. 53.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Naming of Chevy Chase | Chevy Chase Historical Society". www.chevychasehistory.org. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ^ Early Days at the Chevy Chase Club, The Montgomery County Story, Montgomery County Historical Society, November 2001

- ^ "Chevy Chase Club - Club History". www.chevychaseclub.org. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ^ "The Schools of Section Four - Chevy Chase Historical Society". Chevy Chase Historical Society.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Fisher, Marc (February 15, 1999). "Chevy Chase, 1916: For Everyman, a New Lot in Life". The Washington Post.

- ^ https://planning.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/op/publication/attachments/Friendship%2520Heights.draft%2520final.pdf

- ^ https://www.popville.com/2020/12/friendship-heights-is-looking-more-and-more-bare/

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Neate, Rupert (December 4, 2015). "Chevy Chase, Maryland: the super-rich town that has it all – except diversity". The Guardian.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Bethesda, Chevy Chase Homes of The Rich and Famous". Bethesda Magazine. October 10, 2012.

- ^ Arsenault, Raymond (2006), Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199755813

- ^ "Hilary Rhoda - Fashion Model - Profile on New York Magazine". New York Magazine.

- ^ Richards, Chris (May 31, 2013). "Peter Rosenberg: From Montgomery County to top of the hip-hop heap". The Washington Post.

- ^ Giannotto, Mark (February 4, 2011). "Danny Rubin goes from Landon to Boston College walk-on to ACC starter". The Washington Post.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chevy Chase, Maryland. |

- Chevy Chase, Maryland

- 1890 establishments in Maryland

- Sundown towns in Maryland

- Upper class culture in Maryland