Chinatown, Denver

Denver Chinatown | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood of Denver | |

Wazee Street, former site of Chinatown, in LoDo | |

Site of commemorative plaque for Hop Alley / Chinese Riot of 1880 | |

| Coordinates: 39°45′14.22″N 104°59′38.76″W / 39.7539500°N 104.9941000°WCoordinates: 39°45′14.22″N 104°59′38.76″W / 39.7539500°N 104.9941000°W | |

| Country | |

| State | Colorado |

| City | Denver |

| Chinese settlement begins | 1869 |

| Area code(s) | Area code 303 |

Chinatown in Denver, Colorado, was a residential and business district of Chinese Americans in what is now the LoDo section of the city. It was also referred to as "Hop Alley," based upon a slang word for opium.[1] The first Chinese resident of Denver was Hong Lee arrived in 1869 and lived in a shanty at Wazee and F Streets and ran a washing and ironing laundry business. More Chinese immigrants arrived in the town the following year. Men who had worked on the construction of the first transcontinental railroad or had been miners in California crossed over the Rocky Mountains after their work was completed or mines were depleted in California.

In Denver, most of the Chinese operated laundries, picking up a need for Denver's residents. Anti-Chinese sentiment escalated to mob rule in Chinese enclaves throughout the Western United States. In 1880, a white mob attacked Chinese people, their homes and their businesses, virtually destroying all of Chinatown. One man was killed and dozens sustained severe injuries. The Chinese were not compensated for their property loss. Some people moved away soon after the riot, others stayed and rebuilt Chinatown, but the residents continued to experience racial discrimination. By 1940, Chinatown had few Asian inhabitants and the district was razed as part of an urban renewal project.

Location[]

The boundaries of Chinatown changed over time, but extended from approximately 15th to 20th Streets, and from Market to Wazee Streets.[2] There were at least three Chinatown boundaries in the city of Denver, the first established along Wazee Street[3] and the last being located on Market and Larimer Streets.[4]

Migration to Denver[]

Chinese immigrants, most of whom were men,[5] moved from the West Coast where they had been railroad workers, miners, and businesspeople to Colorado.[3][a] Once the transcontinental railroad was completed (May 10, 1869), and California gold mines were depleted, they moved inland. In 1870, they were encouraged to come to Colorado by the Territorial legislature[7] to meet the needs for agricultural and other cheap laborers to "hasten the development and early prosperity of the Territory".[6]

High wages eat up the profits of [Colorado] farms, put an embargo on thousands of lodes that might otherwise be profitable, hinder manufacturers, and act in general as an incubus on our efforts.

— Joseph Woof, in an appeal to import Chinese from California[8]

The June 29, 1869 edition of the Colorado Tribune announced "the first John Chinaman in Denver."[6] Hong Lee lived in a shanty at Wazee and F Streets and ran a washing and ironing laundry business.[9] By the fall of 1870 there were 42 Chinese men and women living along Wazee Street,[7] establishing what was first known as Chinaman's Row.[10] Wazee was probably a Cantonese name for "Street of the Chinese". It was located next to the red-light district on Holliday Street, now Market Street.[8] It was a very poor district, but it provided some safety, a shared cultural heritage, community support, and a place to buy and sell goods unique to their culture.[10] Italians were similarly situated. They lived in a poor neighborhood along the South Platte River between Highland and downtown Denver called "The Bottoms". According to historian Robert Athearn, its residents adapted to living in a hovel because of "the strength of their old-world heritage and their religion."[8]

The town grew quickly, but did not have the infrastructure to manage the influx of people and public health issues. There were open sewers, trash-filled rivers, cows and pigs that freely walked the streets, and carcasses of dead cats and rats in the streets. With the completion of the transatlantic railroad, tuberculosis patients came to Colorado beginning in the 1870s for the dry, sunny climate and high altitudes. Colorado became the "sanatorium to the world" and the disease spread throughout the city. By the 1880s, 10,000 people in Denver had tuberculosis; this was one-third of the city's population. Dr. Frederick J. Bancroft (who created Denver's public health system) claimed that Denver was one of the dirtiest cities in the country. The entire city was not clean, but ethnic enclaves for the Chinese, Italians, and the Irish were worse. Public health became another excuse to oust Chinamen from the city.[11][b] Further: Frances Wisebart Jacobs § Denver's Jewish Hospital Association

By 1880, there were 238 Chinese residents. Of those, 225 were men, most of whom did laundry or worked as cooks.[5][12] Some of the 13 women were prostitutes.[5] A Chinese consul visiting Denver estimated that it was more likely a total of 450 Chinese immigrants.[6] At its peak, there were 980 people in 1890[7] or around 1,400 Chinese immigrants in Denver, which made it the largest enclave of Chinese people in the Rocky Mountains. Most of them lived in decrepit buildings in Chinatown.[2] They had unique cultural rituals, like fireworks during the Chinese New York and long funeral processions through the streets of Denver.[5]

According to William Wei, history professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, "The American West is a vast territory and always suffered from an insufficient number of people to build it up. The Chinese were great workers, reliable and industrious." They took on jobs that others would not do, like working placer mines,[2] where they searched for traces of gold from abandoned mines, or in Denver doing laundry. Laundry was considered women's work, but there were few women in Colorado at that time.[5] Unlike other Colorado residents, most Chinese immigrants intended to save their earnings and retire back in China. The average stay in Colorado was six years.[5]

Located in a busy section of Denver, the Chinese had profitable businesses, like laundromats, or jobs in the service industry. The location, though, "also made them a visible minority in a racially charged society" during a period of anti-Chinese sentiment in the Western United States.[3]

Racial discrimination and anti-Chinese riot of 1880[]

European Americans were suspicious of the Chinese culture beginning in the 1870s. Newspaper articles suggested that the Chinese, descendants of the Mongol Empire, wanted to take over the United States. Chinatown became a scapegoat for vices attributed to the Chinese, but were not found to occur to a greater degree than by whites. The concerns were about opium dens, prostitution, and gambling.[3][6] There was also concern that the Chinese were taking jobs for European Americans;[13] they worked cheaper than any other people.[2] Anti-Chinese sentiment was fueled by Denis Kearney, an Irish-American who stated that Chinese people should be removed from the continent[6] and called for a ban on any Chinese from coming to United States and its territories.[13] During the 1860s and 1870s, race riots occurred throughout the West; the largest were the Los Angeles massacre of 1871 and San Francisco riot of 1877.[3] Within Colorado, "Chinese must go" was the sentiment amongst attacked on Chinese people in Leadville, Nederland, and other communities.[6][13][c] In addition, Chinese people were denied economic opportunities and civil rights.[12]

Immigration of Chinese people was a national issue during the 1880 presidential election. On October 30, 1880, Democratic supporters marched through the streets of Denver, some of them carrying signs with anti-Chinese rhetoric.[13] Two days before the election, a white mob instigated a race riot on October 31, 1880, which killed one Chinese man and virtually destroyed Chinatown. Most of the buildings were ransacked or burned.[13] It began when several drunk white men harassed two Chinese men[13] who were playing pool at a saloon at Wazee and 16th Street.[3][6] To avert a fight, the owner John Asmussen asked the Chinese men to leave out the back door of the bar. They left, but were followed by a man who hit one of the Chinamen over the head with a board.[6][13] It escalated to a riot of about 3,000 men[6] spurred on with calls to "Stamp out the Yellow Plague"[2] and the "Chinese must go".[6] Every visible Chinese person or business was attacked. Called a "Bloody Riot", a number of Chinese were subject to brutal beatings, leaving dozens severely injured.[3][5] A 28 year-old man named Look Young[3][1][d] was beaten and dragged through the streets by a rope around his neck.[13][e] Eight policemen on duty were unable to stop the riot. In the morning Mayor Richard Sopris brought firemen with hose carts and hosed down the mob, who became angrier.[6] Nearly all of Chinatown's business and residential properties were destroyed, at a loss of $53,655 (equivalent to $1,438,879 in 2020). The actual loss may have been far greater because those who left town immediately did not tally their losses.[3] For their safety, 185 Chinese men were held in jail for three days, others hid in barns or houses, or left town.[1]

None of the people that participated in the destruction and murder in Chinatown were held accountable[12] and the Chinese were not compensated for their losses. Some decided to remain in Denver and rebuild,[3][12] but 100 people left the city shortly after the riot. Mattie Silks, a madame, paid for the tickets to allow a group of women to leave town.[5] Chin Lin Sou and his family, as well as the Lung family, were prosperous after the riot.[1][12]

As a result of the anti-Chinese sentiment in the west, legislators passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which effectively banned immigration of people from China. It also meant that Chinese Americans could not apply for citizenship. The law was repealed in 1943.[3]

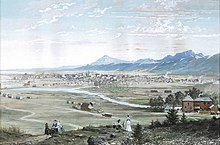

Chinatown in 1885[]

In 1885, Chinatown was located between Wazee and Larimer Streets and 15th to 21st Streets, with Blake Street at its center. Chinese residents were spread out through this area, rather than having a certain street or streets where they all lived. There were 468 people living in Arapahoe County—which in present day encompasses Denver, Arapahoe and Adams counties— who were born in China.[14]

Legacy[]

Denver's Chinese population, dispersed throughout the city, was estimated to have grown to approximately 3,000 around the beginning of the 20th century.[4] Racial discrimination and legislation led to Chinatown's demise.[2] By 1940, there were only 110 Chinese people living in Denver.[3] Dilapidated buildings were razed during an urban renewal project that year.[7][13] While there is no longer a Chinatown, there are pockets of Denver with Asian community members, like Asian markets along South Federal Boulevard.[2] There are Asian Pacific people who live and work in LoDo and throughout the Denver metropolitan area.[12]

The only remaining evidence of the former Chinatown is a plaque on the southeast corner of 20th and Blake Streets that commemorates the riot and former Chinatown.[3][15]

During the 1860's, the first Chinese settled in Colorado, drawn here by the completion of the transcontinental railroad as well as by other demands for cheap manual labor. Existing amidst persecution, poverty and wretched living conditions, the Chinese worked mostly in laundries, as house servants and in the mines. The Chinese neighborhood was bounded roughly by Blake and Market, 19th and 22nd Streets, and contained about 500 Chinese. By 1880, the city had 17 known opium dens in this area, where one could "hit the pipe" or "suck the bamboo." "Hop" Alley buildings were said to be connected by tunnels and secret rooms accessible only by trap doors. Hostilities between the Chinese and other immigrants intensified as competition for jobs increased and negative publicity about opium dens filled the local press. On October 31, 1880, in John Asmussen's Saloon, located on the 1600 block of Wazee, an argument broke out between two pool-playing Chinese and some intoxicated whites. When the Chinese slipped out the back door, they were attacked and beaten, beginning Denver's first recorded race riot. About 3,000 people congregated quickly in the area, shouting "Stamp out the yellow plague!" Destruction of the Chinese ghetto ensued. Several white residents show remarkable courage protecting the Chinese: Saloonkeeper James Veatch sheltered refugees, as did gambler Jim Moon and Madam Lizzie Preston, whose girls armed themselves with champagne bottles and high heels to hold the mob at bay. Many were injured, and one Chinese man lost his life. Despite 150 claims totaling over $30,000, no Chinese were ever paid for property and business losses, nor did this dark day end Denver's struggles with the underlying issues of racial prejudice..[16]

Members of the Colorado Asian Pacific United organization (CAPU) want the plaque replaced with one that they believe better represents the Chinese community and its history.[12]

Notable people[]

- Chin Lin Sou, railroad supervisor, mining businessman, and merchant

Notes[]

- ^ Chinese came to the United States to flee the Taiping Rebellion and upon the discovery of gold in California.[6]

- ^ In 1879 and 1880, Denver formed a Board of Health. Sewage systems were installed in the city, and city ordinances for public health began to be enforced.[11]

- ^ There were 153 race riots against the Chinese in the West during the 1870s and 1880s.[13]

- ^ Some sources incorrectly state that a man named Sing Lee was killed. There was a conflation of the man with his place of business. Look worked for the Sing Lee Laundry.[3]

- ^ He is also said to have been hanged from a lamppost in front of the Markham Hotel, after having been beaten.[1]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e "Race riot tore apart Denver's Chinatown". Eugene Register-Guard. October 30, 1996. Retrieved 2020-10-28 – via Google newspapers.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Remembering when Denver had a Chinatown". The Denver Post. 2011-05-06. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "The Rise and Fall of Denver's Chinatown". www.historycolorado.org. April 11, 2019. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ^ a b Sarah M. Nelson; K. Lynn Berry; Richard F. Carillo; Bonnie J. Clark; Lori E. Rhodes; Dean Saitta (2 January 2009). Denver: An Archaeological History. ISBN 9780870819841.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Trembath, Brian K. (2021-05-13). "What happened to Denver's Chinatown, and its residents?". Denver Public Library History. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Wortman, Roy T. (Fall 1965). "Denver's Anti-Chinese Riot, 1880" (PDF). Colorado Magazine. Vol. 43, no. 4. Colorado Historical Society.

- ^ a b c d Wei, William. "Denver Chinatown". Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ^ a b c Wei 2016, p. 68.

- ^ "The Chinaman in Colorado". The Tarborough Southerner. 1869-08-05. p. 2. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ^ a b Wei 2016, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Wei 2016, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d e f g De Leon, Victoria (August 8, 2021). "Re-Envisioning Denver's Historic Chinatown: An organization hopes that starts with removing an offensive plaque". Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Denver's Anti-Chinese Riot". Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ^ "1885 Colorado State Census - Arapahoe County" (PDF). Denver Public Library. p. ii, xiv, xxii.

- ^ "On Halloween Nearly 150 Years Ago, An Anti-Chinese Riot Broke Out In Denver. It Was The City's First Race Riot".

- ^ "Hop Alley/Chinese Riot of 1880 Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

Sources[]

- Wei, William (2016-04-05). Asians in Colorado: A History of Persecution and Perseverance in the Centennial State. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80636-5.

Further reading[]

- Song, Jingyi (2019-10-29). Denver’s Chinatown 1875-1900: Gone But Not Forgotten. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-41363-4.

- Zhu, Liping (2013). The Road to Chinese Exclusion: The Denver Riot, 1880 Election, and Rise of the West. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1919-1.

- Neighborhoods in Denver

- Chinatowns in the United States

- History of Denver

- Race riots in the United States