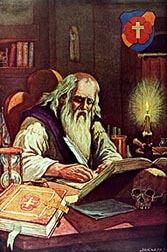

Christian Rosenkreuz

Christian Rosenkreuz (also spelled Rosenkreutz, Rosencreutz, and Christian Rose Cross) is the legendary, possibly allegorical, founder of the Rosicrucian Order (Order of the Rose Cross).[4] He is presented in three manifestos that were published early in the 17th century. These were:

- Fama Fraternitatis (published 1614 in Kassel, Germany) This manifesto introduced the founder, "Frater C.R.C."

- Confessio Fraternitatis (published 1615 in Kassel, Germany)

- The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz (published 1616 in Strasbourg, Germany).

Legend[]

| Part of a series on |

| Hermeticism |

|---|

|

| Mythology |

|

Hermetic arts |

| Hermetic writings |

|

|

Related historical figures (ancient and medieval) |

|

|

Related historical figures (early modern) |

| Modern offshoots |

According to the legend, Christian Rosenkreuz was a medieval German aristocrat, orphaned at the age of four and raised in a monastery, where he studied for twelve years.[4] He discovered and learned esoteric wisdom on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land,[4] among Turkish, Arab, and Persian sages, possibly Sufi or Zoroastrian masters, supposedly in the early 15th century (see § Symbolism of the numbers in the Manifestos); returned and founded the "Fraternity of the Rose Cross" with himself (Frater C.R.C.) as Head of the Order. Under his direction a Temple, called , or "The House of the Holy Spirit", was built.

It is described that his body, as discovered by a Brother of the Order, was in a perfect state of preservation 120 years after his death (which occurred in absolute secrecy) – as Rosenkreuz had predicted — in a heptagonal chamber erected by himself as a storehouse of knowledge. It is described that on the sarcophagus in the centre of the Crypt of Christian Rosenkreutz were written, among other inscriptions the words, "Jesus mihi omnia, nequaquam vacuum, libertas evangelii, dei intacta gloria, legis jugum" ("Jesus is everything to me, by no means empty, the freedom of the gospel, the untouched glory of God, the yoke of the law"), testifying to the builder's Christian character.

Rosenkreuz's crypt, according to the description presented in the legend, is located in the interior of the Earth, recalling the alchemical motto V.I.T.R.I.O.L.: Visita Interiora Terrae Rectificando Invenies Occultum Lapidem ("Visit the interior of the Earth; by rectification thou shalt find the hidden stone").

Biographies[]

According to some researchers, Christian Rosenkreuz was the last descendant of the Germelshausen, a German family which flourished in the 13th century.[5] Their castle stood in the Thuringian Forest on the Border of Hesse and they had embraced Albigensian (i.e., Cathar) doctrines, combining Gnostic and Christian beliefs. The whole family was put to death by Konrad von Marburg except for the youngest son, who was only five years old. He was carried away secretly by a monk who was an Albigensian adept from Languedoc. The child was placed in a monastery which had already come under the influence of the Albigenses, where he was educated and made the acquaintance of the four other brothers who were later to be associated with him in the founding of the Rosicrucian Brotherhood. His account derives from oral tradition.

Some occultists including Rudolf Steiner, Max Heindel[6] and (much later) Guy Ballard, have stated that Rosenkreuz later reappeared as the Count of St. Germain, a courtier, adventurer and alchemist who reportedly died on 27 February 1784. Steiner once identified Rembrandt's painting "A Man in Armour" as a portrait of Christian Rosenkreuz, apparently in a 17th-century manifestation. Others believe Rosenkreuz to be a pseudonym for a more famous historical figure, usually Francis Bacon. Steiner gave lectures on Rosenkreutz and Rosicrucianism.[7]

Symbolism of the numbers in the Manifestos[]

The legend presented in the Manifestos has been interpreted symbolically (as were all hermetic and alchemical texts of those times). They do not directly state Christian Rosenkreuz's years of birth and death, but in two sentences in the second Manifesto the year 1378[8] is presented as being the birth year of "our Christian Father", and it is stated that he lived for 106 years, which would mean he died in 1484.[9] The foundation of the Order can be supposed in similar terms to have occurred in the year 1407. However, these numbers (and deduced years) are not taken literally by many students of occultism, who consider them to be allegorical and symbolic statements for the understanding of the initiated. The justification for this relies on the Manifestos themselves: on the one hand, the Rosicrucians clearly adopted through the Manifestos the Pythagorean tradition of envisioning objects and ideas in terms of their numeric aspects, and, on the other hand, they directly state, "We speak unto you by parables, but would willingly bring you to the right, simple, easy and ingenuous exposition, understanding, declaration, and knowledge of all secrets."[10]

The metaphorical nature of these legends lends a nebulous quality to the origins of Rosicrucianism. The opening of Rosenkreuz's tomb is thought to be a way of referring to the cycles in nature and to cosmic events; and as well, to the opening of new possibilities for mankind consequent on the advances of the 16th and early 17th centuries. Similarly, Rosenkreuz's pilgrimage seems to refer to the transmutation steps of the Great Work.

Similar legends may be found in Wolfram von Eschenbach's description of the Holy Grail as the "Lapis Exillis", guarded by the Knights Templar, or in the Philosophers' stone of the alchemists, the "Lapis Elixir".[11]

See also[]

- Rosicrucian Manifestos

- Rose Cross

- Rosicrucianism

- Hermeticism

- Esoteric Christianity

- Vitriol

References[]

- ^ Cf. John 21:20-25

- ^ Chapter 1 Origins of the Rosicrucian Order. RF Friends (accessed on February 11, 2017)

- ^ European Tradition for Initiation. Anthroposophical Health Studies (accessed on February 11, 2017)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Williard, Thomas (2013). "The Strange Journey of Christian Rosencreutz". In Classen, Albrecht (ed.). East Meets West in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times: Transcultural Experiences in the Premodern World. Fundamentals of Medieval and Early Modern Culture. 14. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 667–698. doi:10.1515/9783110321517.667. ISBN 9783110328783. ISSN 1864-3396.

- ^ Maurice Magre (1877–1941). Magicians, Seers, and Mystics

- ^ Max Heindel, Christian Rosenkreuz and the Order of Rosicrucians, 1909

- ^ "Rosicrucian Esotericism". 1978. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ "from the year of Our Lord 1378 (in which year our Christian Father was born)", in Confessio Fraternitatis

- ^ "in these one hundred and six years [1484?] of his life", Idem

- ^ Cf. Confessio Fraternitatis, the second Rosicrucian Manifesto

- ^ Ralls, Karen (2003). The Templars and the Grail: knights of the quest. Quest Books/Theosophical Pub. House. p. 135. ISBN 0-8356-0807-7.

External links[]

Manifestos

- Works by Christian Rosenkreuz at Project Gutenberg

- Text of the Fama Fraternitatis, 1614, at the Alchemy web site

- Text of the Confessio Fraternitatis, 1615, idem

- Text of The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz, 1616, idem

Studies

- Bamford, Christopher. The Rosicrucian Enlightenment Revisited: The Meaning of the Rose Cross. Lindisfarne Books, 1999 ISBN 0940262843

- Prinke, Rafal T. Michael Sendivogius and Christian Rosenkreutz, The Unexpected Possibilities. The Hermetic Journal, 1990, 72–98 online

- Weber, Charles. Rosicrucianism and Christianity. Rays from the Rose Cross, 1995

- Alchemists

- Christian Kabbalah

- Christian Kabbalists

- Esoteric Christianity

- Hermeticism

- German Christian mystics

- Rosicrucianism