Citizen Lab

| |

| Formation | 2001 |

|---|---|

| Type | Research Laboratory |

| Headquarters | University of Toronto |

| Location | |

Director | Ronald Deibert |

| Website | citizenlab |

The Citizen Lab is an interdisciplinary laboratory based at the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto, Canada. Founded and directed by Professor Ronald Deibert, the Citizen Lab studies information controls—such as network surveillance and content filtering—that impact the openness and security of the Internet and that pose threats to human rights.[1] The Citizen Lab collaborates with research centres, organizations, and individuals around the world, and uses a "mixed methods" approach, which combines computer-generated interrogation, data mining, and analysis with intensive field research, qualitative social science, and legal and policy analysis methods.

The Citizen Lab was a founding partner of the OpenNet Initiative (2002–2013) and the Information Warfare Monitor (2002–2012) projects. The organization also developed the original design of the Psiphon censorship circumvention software, which was spun out of the Lab into a private Canadian corporation (Psiphon Inc.) in 2008.

The Citizen Lab's research outputs have made global news headlines around the world, including front page exclusives in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Globe and Mail. In Tracking GhostNet (2009), researchers uncovered a suspected cyber espionage network of over 1,295 infected hosts in 103 countries, a high percentage of which were high-value targets, including ministries of foreign affairs, embassies, international organizations, news media, and NGOs.[2] This seminal study was one of the first public reports to reveal a cyber espionage network that targeted civil society and government systems around the world. In Shadows in the Cloud (2010), researchers documented a complex ecosystem of cyber espionage that systematically compromised government, business, academic, and other computer network systems in India, the offices of the Dalai Lama, the United Nations, and several other countries.[3] In Million Dollar Dissident,[4] published in August 2016, researchers discovered that Ahmed Mansoor, one of the UAE Five, a human rights defender in the United Arab Emirates, was targeted with software developed by Israeli "cyber war" company NSO Group. Using a chain of zero-day exploits, operators of this spyware attempted to get Mansoor to click on a link in a socially engineered text message that would have given them access to everything in his phone. Prior to the releases of the report, researchers contacted Apple who released a security update that patched the vulnerabilities exploited by the spyware operators.

The Citizen Lab has won a number of awards for its work. It is the first Canadian institution to win the MacArthur Foundation’s MacArthur Award for Creative and Effective Institutions (2014)[5] and the only Canadian institution to receive a "New Digital Age" Grant (2014) from Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt.[6] Past awards include the Electronic Frontier Foundation Pioneer award (2015),[7] the Canadian Library Association's Advancement of Intellectual Freedom in Canada Award (2013),[8] the Canadian Committee for World Press Freedom's Press Freedom Award (2011),[9] and the Canadian Journalists for Free Expression’s Vox Libera Award (2010).[10]

According to a January 24, 2019 AP News report, Citizen Lab researchers "are being targeted" by "international undercover operatives" for its work on NSO Group.[11]

Funding[]

Financial support for the Citizen Lab has come from the Ford Foundation, the Open Society Institute, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), the Government of Canada, the Canada Centre for Global Security Studies at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Donner Canadian Foundation, the Open Technology Fund, and The Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation. The Citizen Lab has received donations of software and support from Palantir Technologies, VirusTotal, and Oculus Info Inc.[12]

Research areas[]

Threats against civil society[]

The Citizen Lab’s Targeted Threats research stream seeks to gain a better understanding of the technical and social nature of digital attacks against civil society groups and the political context that may motivate them.[13] The Citizen Lab conducts ongoing comparative analysis of a growing spectrum of online threats, including Internet filtering, denial-of-service attacks, and targeted malware. Targeted Threats reports have covered a number of espionage campaigns and information operations against the Tibetan community and diaspora,[14] phishing attempts made against journalists, human rights defenders, political figures, international investigators and anti-corruption advocates in Mexico,[15] and a prominent human rights advocate who was the focus of government surveillance in the United Arab Emirates.[4] Citizen Lab researchers and collaborators like the Electronic Frontier Foundation have also revealed several different malware campaigns targeting Syrian activists and opposition groups in the context of the Syrian Civil War.[16] Many of these findings were translated into Arabic and disseminated along with recommendations for detecting and removing malware.

The Citizen Lab’s research on threats against civil society organizations has been featured on the front page of BusinessWeek,[17] and covered in Al Jazeera,[18] Forbes,[19] Wired,[20] among other international media outlets.

The group reports that their work analyzing spyware used to target opposition figures in South America has triggered death threats.[21][22] In September 2015 members of the group received a pop-up that said:

|

We're going to analyze your brain with a bullet—and your family's, too ... You like playing the spy and going where you shouldn't, well you should know that it has a cost—your life![21][22] |

Measuring Internet censorship[]

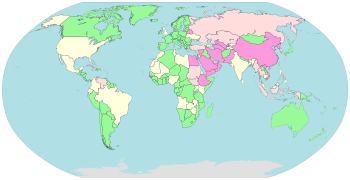

Sources: Freedom on the Net,[23] OpenNet Initiative,[24][25] Reporters Without Borders.[26][27]

The OpenNet Initiative has tested for Internet filtering in 74 countries and found that 42 of them—including both authoritarian and democratic regimes—implement some level of filtering.[28]

The Citizen Lab continued this research area through the Internet Censorship Lab (ICLab), a project aimed at developing new systems and methods for measuring Internet censorship. It was a collaborative effort between the Citizen Lab, Professor Phillipa Gill's group at Stony Brook University's Department of Computer Science, and Professor Nick Feamster's Network Operations and Internet Security Group at Princeton University.[29]

Application-level information controls[]

The Citizen Lab studies censorship and surveillance implemented in popular applications including social networks, instant messaging, and search engines.

Previous work includes investigations of censorship practices of search engines provided by Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo! for the Chinese market along with the domestic Chinese search engine Baidu. In 2008, Nart Villeneuve found that TOM-Skype (the Chinese version of Skype at the time) had collected and stored millions of chat records on a publicly accessible server based in China.[30] In 2013, Citizen Lab researchers collaborated with Professor Jedidiah Crandall and Ph.D. student Jeffrey Knockel at the University of New Mexico to reverse engineering of TOM-Skype and , another instant messaging application used in China. The team was able to obtain the URLs and encryption keys for various versions of these two programs and downloaded the keyword blacklists daily. This work analyzed over one year and a half of data from tracking the keyword lists, examined the social and political contexts behind the content of these lists, and analyzed those times when the list had been updated, including correlations with current events.[31]

Current research focuses on monitoring information controls on the popular Chinese microblogging service Sina Weibo,[32] Chinese online encyclopedias,[33] and mobile messaging applications popular in Asia.[34] The Asia Chats project utilizes technical investigation of censorship and surveillance, assessment on the use and storage of user data, and comparison of the terms of service and privacy policies of the applications.[35] The first report released from this project examined regional keyword filtering mechanisms that LINE applies to its Chinese users.[36]

Analysis of a popular cellphone app called "Smart Sheriff", by Citizen Lab and the German group Cure53, asserted the app represented a security hole that betrayed the privacy of the children it was meant to protect and that of their parents.[37] South Korean law required all cellphones sold to those under 18 to contain software designed to protect children, and Smart Sheriff was the most popular government approved app—with 380,000 subscribers. The Citizen Lab/Cure53 report described Smart Sheriff's security holes as "catastrophic".[38]

Commercial surveillance[]

The Citizen Lab conducts groundbreaking research on the global proliferation of targeted surveillance software and toolkits, including FinFisher, Hacking Team and NSO Group.

FinFisher is a suite of remote intrusion and surveillance software developed by Munich-based Gamma International GmbH and marketed and sold exclusively to law enforcement and intelligence agencies by the UK-based Gamma Group. In 2012, Morgan Marquis-Boire and Bill Marczak provided the first public identification of FinFisher's software. The Citizen Lab and collaborators have done extensive investigations into FinFisher, including revealing its use against Bahraini activists,[39] analyzing variants of the FinFisher suite that target mobile phone operating systems,[40] uncovering targeted spying campaigns against political dissidents in Malaysia and Ethiopia,[41] and documenting FinFisher command and control servers in 36 countries.[42] Citizen Lab's FinFisher research has informed and inspired responses from civil society organizations in Pakistan,[43] Mexico,[44] and the United Kingdom.[45] In Mexico, for example, local activists, and politicians collaborated to demand an investigation into the state's acquisition of surveillance technologies.[46] In the UK, it led to a crackdown on the sale of the software over worries of misuse by repressive regimes.[47]

Hacking Team is a company based in Milan, Italy, that provides intrusion and surveillance software called Remote Control System (RCS) to law enforcement and intelligence agencies. The Citizen Lab and collaborators have mapped out RCS network endpoints in 21 countries,[48] and have revealed evidence of RCS being used to target a human rights activist in the United Arab Emirates,[49] a Moroccan citizen journalist organization,[50] and an independent news agency run by members of the Ethiopian diaspora.[51] Following the publication of Hacking Team and the Targeting of Ethiopian Journalists, the Electronic Frontier Foundation[52] and Privacy International[53] both took legal action related to allegations that the Ethiopian government had compromised the computers of Ethiopian expatriates in the United States and UK.

In 2018, the Citizen Lab released an investigation into the global proliferation of Internet filtering systems manufactured by the Canadian company, Netsweeper, Inc. Using a combination of publicly available IP scanning, network measurement data, and other technical tests, they identified Netsweeper installations designed to filter Internet content operational on networks in 30 countries and focused on 10 with past histories of human rights challenges: Afghanistan, Bahrain, India, Kuwait, Pakistan, Qatar, Somalia, Sudan, UAE, and Yemen. Websites blocked in these countries include religious content, political campaigns, and media websites. Of particular interest was Netsweeper's ‘Alternative Lifestyles’ category, which appears to have as one of its principal purposes the blocking of non-pornographic LGBTQ content, including that offered by civil rights and advocacy organizations, HIV/AIDS prevention organizations, and LGBTQ media and cultural groups. The Citizen Lab called on government agencies to abandon the act of filtering LGBT content.[54]

Since 2016, Citizen Lab has published a number of reports on "Pegasus", a spyware for mobile devices that was developed by the NSO Group, an Israeli-based cyber intelligence firm.[55] Citizen Lab's ten part series on the NSO Group ran from 2016 through 2018. The August 2018 report was timed to coordinate with Amnesty International's in-depth report on the NSO Group.[56][Notes 1][4][57][58][59][60][61][15][62][63][55]

In 2017, the group released several reports that showcased phishing attempts in Mexico that used NSO Group technology. The products were used in multiple attempts to gain control of mobile devices of Mexican government officials, journalists, lawyers, human rights advocates and anti-corruption workers.[64] The operations used SMS messages as bait in an attempt to trick targets into clicking on links to the NSO Group's exploit infrastructure. Clicking on the links would lead to the remote infection of a target's phone. In one case, the son of one of the journalists—a minor at the time—was also targeted. NSO, who purports to only sell products to governments, also came under the group's focus when prominent UAE human rights defender Ahmed Mansoor's mobile phone was targeted. The report on these attempts showed the first time iOS zero day exploits in the wild and prompted Apple to release a security update to their iOS 9.3.5, affecting more than 1 billion Apple users worldwide.

In 2020, the Citizen Lab released a report unveiling Dark Basin, a hack-for-hire group based in India.[65]

The Citizen Lab's research on surveillance software has been featured on the front pages of The Washington Post[66] and The New York Times[67] and covered extensively in news media around the world, including the BBC,[68] Bloomberg,[69] CBC, Slate,[70] and Salon.[71]

The Citizen Lab's research on commercial surveillance technologies has resulted in legal and policy impacts. In December 2013, the Wassenaar Arrangement was amended to include two new categories of surveillance systems on its Dual Use control list—"intrusion software" and "IP Network surveillance systems".[72] The Wassenaar Arrangement seeks to limit the export of conventional arms and dual-use technologies by calling on signatories to exchange information and provide notification on export activities of goods and munitions included in its control lists. The amendments in December 2013 were the product of intense lobbying by civil society organizations and politicians in Europe, whose efforts were informed by Citizen Lab's research on intrusion software like FinFisher and surveillance systems developed and marketed by Blue Coat Systems.[73]

Commercial filtering[]

The Citizen Lab studies the commercial market for censorship and surveillance technologies, which consists of a range of products that are capable of content filtering as well as passive surveillance.

The Citizen Lab has been developing and refining methods for performing Internet-wide scans to measure Internet filtering and detect externally visible installations of URL filtering products. The goal of this work is to develop simple, repeatable methodologies for identifying instances of internet filtering and installations of devices used to conduct censorship and surveillance.

The Citizen Lab has conducted research into companies such as Blue Coat Systems, Netsweeper, and SmartFilter. Major reports include "Some Devices Wander by Mistake: Planet Blue Coat Redux" (2013),[74] "O Pakistan, We Stand on Guard for Thee: An Analysis of Canada-based Netsweeper’s Role in Pakistan’s Censorship Regime" (2013),[75] and Planet Blue Coat: Mapping Global Censorship and Surveillance Tools (2013).[76]

This research has been covered in news media around the world, including the front page of The Washington Post,[77] The New York Times,[78] The Globe and Mail,[79] and the Jakarta Post.[80]

Following the 2011 publication of "Behind Blue Coat: Investigations of Commercial Filtering in Syria and Burma", Blue Coat Systems officially announced that it would no longer provide "support, updates. or other services" to software in Syria.[81] In December 2011, the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of Industry and Security reacted to the Blue Coat evidence and imposed a $2.8 million fine on the Emirati company responsible for purchasing filtering products from Blue Coat and exporting them to Syria without a license.

Citizen Lab's Netsweeper research has been cited by Pakistani civil society organizations Bytes for All and in public interest litigation against the Pakistani government and in formal complaints to the High Commission (Embassy) of Canada to Pakistan.[82]

Corporate Transparency and Government Accountability[]

The Citizen Lab examines transparency and accountability mechanisms relevant to the relationship between corporations and state agencies regarding personal data and other surveillance activities. This research has investigated the use of Artificial Intelligence in Canada's immigration and refugee systems (co-authored by the International Human Rights Program at the University of Toronto's Faculty of Law),[83] an analysis of ongoing encryption debates in the Canadian context (co-authored by the Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic),[84] and a close look at consumer personal data requests in Canada.[85]

In the summer of 2017, the Government of Canada introduced new national security legislation, Bill C-59 (the National Security Act). It proposed to significantly change Canada's national security agencies and practices, including Canada's signals intelligence agency (the Communications Security Establishment). Since the Bill was first proposed, a range of civil society groups and academics have called for significant amendments to the proposed Act. A co-authored paper by the Citizen Lab and the Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic represented the most detailed and comprehensive analysis of CSE-related reforms to date.[86] This analysis was produced to help members of parliament, journalists, researchers, lawyers, and civil society advocates engage more effectively on these issues and was included in parliamentary committee debates and highlighted in dozens of media reports.

Policy engagement[]

The Citizen Lab is an active participant in various global discussions on Internet governance, such as the Internet Governance Forum, ICANN, and the United Nations Government Group of Experts on Information and Telecommunications.

Since 2010, the Citizen Lab has helped organize the annual Cyber Dialogue conference, hosted by the Munk School of Global Affairs’ Canada Centre, which convenes over 100 individuals from countries around the world who work in government, civil society, academia, and private enterprise in an effort to better understand the most pressing issues in cyberspace.[87] The Cyber Dialogue has a participatory format that engages all attendees in a moderated dialogue on Internet security, governance, and human rights. Other conferences around the world, including a high-level meeting by the Hague-based Scientific Council for Government Policy and the Swedish government's , have taken up themes inspired by discussions at the Cyber Dialogue.

Field building[]

The Citizen Lab contributes to field building by supporting networks of researchers, advocates, and practitioners around the world, particularly from the Global South. The Citizen Lab has developed regional networks of activists and researchers working on information controls and human rights for the past ten years. These networks are in Asia (OpenNet Asia), the Commonwealth of Independent States (OpenNet Eurasia), and the Middle East and North Africa.[88]

With the support of the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), the Citizen Lab launched the Cyber Stewards Network in 2012, which consists of South-based researchers, advocates, and practitioners who analyze and impact cybersecurity policies and practices at the local, regional, and international level. The project consists of 24 partners from across Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East and North Africa[89] including 7iber, OpenNet, and the Centre for Internet and Society.

Citizen Lab staff also work with local partners to educate and train at-risk communities. For example, in 2013 it collaborated with the Tibet Action Institute to hold public awareness events in Dharamshala, India, for the exiled Tibetan community on cyber espionage campaigns.[90] In the winter of 2013, the Citizen Lab conducted a digital security training session for Russian investigative journalists at the Sakharov Center in Moscow.[91]

In the media[]

The Citizen Lab's work is often cited in media stories relating to digital security, privacy controls, government policy, human rights, and technology. Since 2006, they have been featured on 24 front-page stories at publications including The New York Times, Washington Post, Globe and Mail and International Herald Tribune.

Citizen Lab Summer Institute[]

Since 2013, Citizen Lab has hosted the Summer Institute on Monitoring Internet Openness and Rights as an annual research workshop at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto. It brings together researchers and practitioners from academia, civil society, and the private sector who are working on Internet openness, security, and rights. Collaborations formed at CLSI workshops have led to publication of high impact reports on Internet filtering in Zambia,[92] a security audit of child monitoring apps in South Korea,[93][94] and an analysis of the "Great Cannon",[95] an attack tool in China used for large scale distributed-denial of service attacks against Github and GreatFire.org.

Undercover agents target Citizen Lab[]

According to a report by AP News journalist Raphael Satter, Citizen Lab researchers who reported in October 2018, that Israeli NSO Group surveillance software was used to spy on the "inner circle" of Jamal Khashoggi just before his murder, "are being targeted in turn by international undercover operatives." Citizen Lab October report revealed that NSO's "signature spy software" which had been placed on the iPhone of Saudi dissident Omar Abdulaziz, one of Khashoggi’s confidantes, months before. Abdulaziz said that Saudi Arabia spies used the hacking software to reveal Khashoggi's "private criticisms of the Saudi royal family". He said this "played a major role" in his death.[11][96]

In March 2019, The New York Times reported that Citizen Lab had been a target of UAE contractor DarkMatter.[97]

In November 2019, Ronan Farrow released a Podcast called "Catch and Kill," an extension of his book of the same name. The first episode includes Farrow's reporting on an instance in which a source of Farrow's was involved in a counter-espionage incident while operatives from Black Cube were targeting Citizen Lab.[98]

Notes[]

- ^ These were published in this order: Part 1: August 24, 2016 "The Million Dollar Dissident: NSO Group's iPhone Zero-Days used against a UAE Human Rights Defender", Part 2: February 11, 2017 "Bittersweet: Supporters of Mexico's Soda Tax Targeted With NSO Exploit Links", Part 4: June 29, 2017 "Reckless Redux: Senior Mexican Legislators and Politicians Targeted with NSO Spyware", Part 5: July 10, 2017 "Reckless III: Investigation Into Mexican Mass Disappearance Targeted with NSO Spyware", Part 3: June 19, 2017 "Reckless Exploit: Mexican Journalists, Lawyers, and a Child Targeted with NSO Spyware", Part 6: August 2, 2017 "Reckless IV: Lawyers For Murdered Mexican Women's Families Targeted with NSO Spyware", Part 7: August 30, 2017 "Reckless V: Director of Mexican Anti-Corruption Group Targeted with NSO Group’s Spyware", Part 8: July 31, 2018 "NSO Group Infrastructure Linked to Targeting of Amnesty International and Saudi Dissident", Part 9: September 18, 2018 "Hide and Seek: Tracking NSO Group’s Pegasus Spyware to Operations in 45 Countries", Part 10: October 1, 2018 "The Kingdom came to Canada: How Saudi-Linked Digital Espionage Reached Canadian Soil"

References[]

- ^

"BPR Interview: Citizens Lab Director Ronald Deibert". Brown Political Review. October 21, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

BPR interviewed Ronald Deibert, director of Citizens Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, an interdisciplinary research organization focusing at the intersection of internet, global security and human rights. They have worked for the office of the Dalai Lama.

- ^ "Tracking Ghostnet: Investigating a Cyber Espionage Network" (PDF). Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Shadows in the Cloud: Investigating Cyber Espionage 2.0". Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Marczak, Bill; Scott-Railton, John (August 24, 2016). "The Million Dollar Dissident: NSO Group's iPhone Zero-Days used against a UAE Human Rights Defender". The Citizen Lab. Reckless (1). Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ "MacArthur Award for Creative and Effective Institutions: The Citizen Lab". February 19, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt Awards Citizen Lab "New Digital Age" Grant". March 10, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Release, Press (August 26, 2015). "EFF Announces 2015 Pioneer Award Winners: Caspar Bowden, Citizen Lab, Anriette Esterhuysen and the Association for Progressive Communications, and Kathy Sierra". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "The Citizen Lab wins the 2013 CLA Advancement of Intellectual Freedom in Canada Award". February 6, 2013. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Citizen Lab Wins the 2011 Canadian Committee for World Press Freedom's Press Freedom Award". May 3, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Canadian Internet Pioneer, The Citizen Lab, Wins Canadian Journalists for Free Expression Vox Libera award". November 15, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Satter, Raphael (January 25, 2019). "APNewsBreak: Undercover agents target cybersecurity watchdog". The Seattle Times via AP News. New York. Retrieved January 26, 2019. Updated January 26

- ^ About Citizen Lab

- ^ "Comparative Analysis of Targeted Threats Against Human Rights Organizations". Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Kleemola, Katie; Hardy, Seth (August 2, 2013). "Surtr: Malware Family Targeting the Tibetan Community". Retrieved March 24, 2014.; "Permission to Spy: An Analysis of Android Malware Targeting Tibetans". April 18, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2014.; "Recent Observations in Tibet-Related Information Operations: Advanced social engineering for the distribution of LURK malware". July 26, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Scott-Railton, John; Marczak, Bill; Razzak, Bahr Abdul; Crete-Nishihata, Masashi; Deibert, Ron (August 30, 2017). "Reckless V: Director of Mexican Anti-Corruption Group Targeted with NSO Group's Spyware". Reckless (7). Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Marquis-Boire, Morgan; Hardy, Seth (June 19, 2012). "Syrian Activists Targeted with Blackshades Spy Software". Retrieved March 24, 2014.; Scott-Railton, John; Marquis-Boire, Morgan (June 21, 2013). "A Call to Harm: New Malware Attacks Target the Syrian Opposition". Retrieved March 24, 2014.; Marquis-Boire, Morgan; Galperin, Eva; Scott-Railton, John (December 23, 2013). "Quantum of Surveillance: Familiar Actors and Possible False Flags in Syrian Malware Campaigns". Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Stephan Farris (November 15, 2012). "The Hackers of Damascus". Bloomberg Businessweek.

- ^ "New report exposes digital front of Syria's civil war". Al Jazeera. December 25, 2013.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy (April 1, 2013). "Evidence Mounts That Chinese Government Hackers Spread Android Malware".

- ^ Poulsen, Kevin (December 23, 2013). "In Syria's Civil War, Facebook Has Become a Battlefield".

- ^ Jump up to: a b

Frank Bajak (December 15, 2015). "South American hackers attacking journalists, opposition, U of T team finds". Toronto Star. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

Researchers said Packrat sent a top Argentine journalist, Jorge Lanata, the identical virus that Nisman received a month before his death.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Packrat malware targets dissidents, journalists in South America, Citizen Lab finds: Probe started after Packrat targeted Argentine special prosecutor found dead of gunshot wound". CBC News. December 9, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ "Freedom on the Net 2018" (PDF). Freedom House. November 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ OpenNet Initiative "Summarized global Internet filtering data spreadsheet", November 8, 2011 and "Country Profiles", the OpenNet Initiative is a collaborative partnership of the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto; the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University; and the SecDev Group, Ottawa

- ^ Due to legal concerns the OpenNet Initiative does not check for filtering of child pornography and because their classifications focus on technical filtering, they do not include other types of censorship.

- ^ "Internet Enemies" Archived March 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Enemies of the Internet 2014: Entities at the heart of censorship and surveillance, Reporters Without Borders (Paris), March 11, 2014. Retrieved June 24, 2014.

- ^ Internet Enemies Archived March 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Reporters Without Borders (Paris), March 12, 2012

- ^ "OpenNet Initiative". Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Internet Censorship Lab". Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ "Breaching Trust: An analysis of surveillance and security practices on China's TOM-Skype platform". 2008.

- ^ "Chat program censorship and surveillance in China: Tracking TOM-Skype and Sina UC". July 2013.

- ^ "Keyword: Bo Xilai". Retrieved March 24, 2014.; "Visualizing Changes in Censorship: Summarizing two months of Sina Weibo keyword monitoring with two interactive charts". August 21, 2013.

- ^ "Who's the Boss? The difficulties of identifying censorship in an environment with distributed oversight: a large-scale comparison of Wikipedia China with Hudong and Baidu Baike". August 28, 2013.

- ^ "Asia Chats: Analyzing Information Controls and Privacy in Asian Messaging Applications". November 14, 2013.

- ^ "Asia Chats: Analyzing Information Controls and Privacy in Asian Messaging Applications". November 14, 2013.

- ^ "Asia Chats: Investigating Regionally-based Keyword Censorship in LINE". August 14, 2013.

- ^

Max Lewontin (November 2, 2015). "South Korea pulls plug on child surveillance app after security concerns: Government officials pulled Smart Sheriff, an app that lets parents track how their children use social media, from the Google Play store over the weekend". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

But researchers from Citizens Lab, a research group based at the University of Toronto, and Cure53, a German software company, released two reports in September finding that Smart Sheriff had a variety of security issues that it made it vulnerable to hackers and put children and parents’ personal information at risk.

- ^

Raphael Satter, Youkyung Lee (November 2, 2015). "South Korea shuts down child surveillance app over security concerns: The removal of the state-approved Smart Sheriff is a blow to South Korea's effort to keep closer tabs on the online lives of youth". Seoul: Toronto Star. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

Pulling the plug on Smart Sheriff was "long overdue," said independent researcher Collin Anderson, who worked with Internet watchdog group Citizen Lab and German software auditing firm Cure53 to comb through the app’s code.

- ^ Marquis-Boire, Morgan; Marczak, Bill (July 25, 2012). "From Bahrain With Love: FinFisher's Spykit Exposed?".

- ^ Marquis-Boire, Morgan; Marczak, Bill; Gaurnieri, Claudio (August 29, 2012). "The Smartphone Who Loved Me? FinFisher Goes Mobile".

- ^ Marquis-Boire, Morgan; Marczak, Bill; Gaurnieri, Claudio; Scott-Railton, John (April 30, 2013). "For Their Eyes Only: The Commercialization of Digital Spying".

- ^ Marquis-Boire, Morgan; Marczak, Bill; Gaurnieri, Claudio; Scott-Railton, John (March 13, 2013). "You Only Click Twice: FinFisher's Global Proliferation".

- ^ "Bytes for All Petitions Pakistani Court on Presence of Surveillance Software". May 16, 2013. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Cyber Stewards Network and Local Activists Investigate FinFisher in Mexico". November 8, 2013.

- ^ "OECD complaint filed by human rights groups against British surveillance company moves forward". June 24, 2013. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Renata Avila (November 8, 2013). "Cyber Steward Network and Local Activists Investigate Surveillance in Mexico". Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Jamie Doward (September 8, 2012). "Crackdown on sale of UK spyware over fears of misuse by repressive regimes".

- ^ Marczak, Bill; Gaurnieri, Claudio; Marquis-Boire, Morgan; Scott-Railton, John (February 17, 2014). "Mapping Hacking Team's "Untraceable" Spyware".

- ^ Morgan Marquis-Boire (October 10, 2012). "Backdoors Are Forever? Hacking Team and the Targeting of Dissent".; Vernon Silver (October 10, 2012). "Spyware Leaves Trail to Beaten Activist through Microsoft Flaw".

- ^ Morgan Marquis-Boire (October 10, 2012). "Backdoors Are Forever? Hacking Team and the Targeting of Dissent".; Nicole Perlroth (October 10, 2012). "Ahead of Spyware Conference More Evidence of Abuse".

- ^ Marczak, Bill; Gaurnieri, Claudio; Marquis-Boire, Morgan; Scott-Railton, John (February 12, 2014). "Hacking Team and the Targeting of Ethiopian Journalists".

- ^ "American Sues Ethiopian Government for Spyware Infection". Electronic Frontier Foundation. February 18, 2014.

- ^ "Privacy International seeking investigation into computer spying on refugee in UK". Privacy International. February 17, 2014. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Citizen Lab Open Letter in Advance of the Equal Rights Coalition Global Conference (August 5–7, 2018, in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada)". The Citizen Lab. July 31, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Amnesty International Among Targets of NSO-powered Campaign". August 1, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2019. Updated October 1, 2018

- ^ Marczak, Bill; Scott-Railton, John; Deibert, Ron (July 31, 2018). "NSO Group Infrastructure Linked to Targeting of Amnesty International and Saudi Dissident". The Citizen Lab. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Scott-Railton, John; Marczak, Bill; Guarnieri, Claudio; Crete-Nishihata, Masashi (February 11, 2017). "Bittersweet: Supporters of Mexico's Soda Tax Targeted With NSO Exploit Links". The Citizen Lab. Reckless (2). Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Scott-Railton, John; Marczak, Bill; Razzak, Bahr Abdul; Crete-Nishihata, Masashi; Deibert, Ron (June 19, 2017). "Reckless Exploit: Mexican Journalists, Lawyers, and a Child Targeted with NSO Spyware". The Citizen Lab. Reckless (3). Retrieved January 26, 2019. Lea la investigación de R3D, SocialTic y Articulo19 (in Spanish)

- ^ Scott-Railton, John; Marczak, Bill; Guarnieri, Claudio; Crete-Nishihata, Masashi; Razzak, Bahr Abdul; Deibert, Ron (June 29, 2017). "Reckless Redux: Senior Mexican Legislators and Politicians Targeted with NSO Spyware". The Citizen Lab. Reckless (4). Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Scott-Railton, John; Marczak, Bill; Razzak, Bahr Abdul; Crete-Nishihata, Masashi; Deibert, Ron (July 10, 2017). "Reckless III: Investigation Into Mexican Mass Disappearance Targeted with NSO Spyware". The Citizen Lab. Reckless (5). Retrieved January 26, 2019. Leer el post de R3D

- ^ Scott-Railton, John; Marczak, Bill; Razzak, Bahr Abdul; Crete-Nishihata, Masashi; Deibert, Ron (August 2, 2017). "Reckless IV: Lawyers For Murdered Mexican Women's Families Targeted with NSO Spyware". The Citizen Lab. Reckless (6). Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Marczak, Bill; Scott-Railton, John; McKune, Sarah; Razzak, Bahr Abdul; Deibert, Ron (September 18, 2018). "Hide and Seek: Tracking NSO Group's Pegasus Spyware to Operations in 45 Countries". The Citizen Lab. Reckless (9). Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ Marczak, Bill; Scott-Railton, John; Senft, Adam; Razzak, Bahr Abdul; Deibert, Ron (October 1, 2018). "The Kingdom Came to Canada: How Saudi-Linked Digital Espionage Reached Canadian Soil". The Citizen Lab. Reckless (10). Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ "Collection of reports on phishing attempts using NSO technology in the United Arab Emirates and Mexico".

- ^ "Toronto's Citizen Lab uncovers massive hackers-for-hire organization 'Dark Basin' that has targeted hundreds of institutions on six continents". Financial Post. June 9, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Craig Timberg (February 12, 2014). "Foreign regimes use spyware against journalists, even in U.S." The Washington Post.

- ^ Nicole Perlroth (August 30, 2012). "Software Meant to Fight Crime is Used to Spy on Dissidents". The New York Times.

- ^ "Mozilla accuses Finfisher makers of 'hiding' under name". BBC. May 1, 2013.

- ^ Vernon Silver (March 13, 2013). "Gamma FinSpy Surveillance Servers in 25 Countries". Bloomberg Businessweek.

- ^ Ryan Gallagher (March 13, 2013). "Report: Global Network of Government Spyware Detected in U.S., Authoritarian Countries". Slate.

- ^ Natasha Lennard (March 13, 2013). "Surveillance software used to spy on activists around the world". Salon.

- ^ "International agreement reached controlling export of mass and intrusive surveillance technology". Privacy International. December 9, 2013. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Shedding Light on the Surveillance Industry: The importance of evidence-based, impartial research". December 20, 2013.

- ^ Marquis-Boire, Morgan; Anderson, Collin; Dalek, Jakub; McKune, Sarah; Scott-Railton, John (July 9, 2013). "Some Devices Wander By Mistake: Planet Blue Coat Redux".

- ^ Jakub Dalek, Adam Senft, Masashi Crete-Nishihata, and Ron Deibert (June 20, 2013). "O Pakistan, We Stand on Guard for Thee: An Analysis of Canada-based Netsweeper's Role in Pakistan's Censorship Regime".CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Marquis-Boire, Morgan; Dalek, Jakub; McKune, Sarah (January 15, 2013). "Planet Blue Coat: Mapping Global Censorship and Surveillance Tools".

- ^ Ellen Nakashima (July 8, 2013). "Report: Web monitoring devices made by U.S. firm Blue Coat detected in Iran, Sudan". The Washington Post.

- ^ John Markoff (January 16, 2013). "Rights Group Reports on Abuses of Surveillance and Censorship Technology". The New York Times.

- ^ Omar El Akkad (June 21, 2013). "Canadian technology tied to online censorship in Pakistan". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Irene Poetranto (December 14, 2013). "Time for Greater Transparency". The Jakarta Post.

- ^ Jakub Dalek and Adam Senft (November 9, 2011). "Behind Blue Coat: Investigations of commercial filtering in Syria and Burma".

- ^ "Letter to High Commissioner Of Canada : Call for Transparency, Accountability & Action Following Reports On Netsweeper's Presence in Pakistan". Bolo Bhi. July 23, 2013.

- ^ "Bots at the Gate: A Human Rights Analysis of Automated Decision Making in Canada's Immigration and Refugee System". The Citizen Lab. September 26, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "Shining a Light on the Encryption Debate: A Canadian Field Guide". The Citizen Lab. May 14, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "Approaching Access: A look at consumer personal data requests in Canada". The Citizen Lab. February 12, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "Citizen Lab and CIPPIC Release Analysis of the Communications Security Establishment Act". The Citizen Lab. December 18, 2017. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ "Cyber Dialogue". Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "ONI Asia". Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Cyber Stewards Network". Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Tibet Action Institute: Safe Travels Online Tech Meet". June 12, 2013. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Дискуссия "Современные угрозы информационной безопасности для НКО, активистов и журналистов"". Sakharov Center. December 17, 2013.

- ^ "Zambia: Internet censorship during the 2016 general elections?".

- ^ Collin Anderson, Masashi Crete-Nishihata, Chris Dehghanpoor, Ron Deibert, Sarah McKune, Davi Ottenheimer, and John Scott-Railton (September 20, 2015). "Are the Kids Alright?".CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Fabian Faessler, Geoffrey Alexander, Masashi Crete-Nishihata, Andrew Hilts, and Kelly Kim (September 11, 2017). "Safer Without: Korean Child Monitoring and Filtering Apps".CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Bill Marczak, Nicholas Weaver, Jakub Dalek, Roya Ensafi, David Fifield, Sarah McKune, Arn Rey, John Scott-Railton, Ron Deibert, and Vern Paxson (April 10, 2015). "China's Great Cannon".CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ According to Raphael Satter's January 25 article, Citizen Lab "has drawn attention for its repeated exposés of NSO Group", whose "wares have been used by governments to target journalists in Mexico, opposition figures in Panama and human rights activists in the Middle East".

- ^ "A New Age of Warfare: How Internet Mercenaries Do Battle for Authoritarian Governments". The New York Times. March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Jared Goyette Ronan Farrow launches Catch and Kill podcast: ‘A reservoir of raw material’; Each episode of podcast based on his bestselling book is built on an interview with a subject from the book, combined with audio recorded in real time during the Weinstein investigation 27 November 2019

External links[]

- University of Toronto

- Laboratories in Canada

- Computer surveillance

- Internet-related organizations

- 2001 establishments in Ontario

- Organizations established in 2001