Cog (ship)

A cog is a type of ship that first appeared in the 10th century, and was widely used from around the 12th century on. Cogs were clinker-built, generally of oak. These vessels were fitted with a single mast and a square-rigged single sail. They were mostly associated with seagoing trade in north-west medieval Europe, especially the Hanseatic League. Typical seagoing cogs ranged from about 15 to 25 meters (49 to 82 ft) in length, with a beam of 5 to 8 meters (16 to 26 ft) and were 30–200 tons burthen. Cogs were rarely as large as 300 tons although a few were considerably larger, over 1,000 tons.

Although the name cog is recorded as early as the 9th century, the seagoing vessel of that name seems to have evolved on the Frisian coast during the 12th century. Cogs progressively replaced Viking-type ships in northern waters during the 13th century. Why this was the case is uncertain, but cogs could carry more cargo than knarr of a similar size. Their flat bottoms allowed them to settle on a level in harbour, making them easier to load and unload. Their high sides made them more difficult to board in a sea fight, which may have made them safer from pirates.

Description and construction[]

Cogs were a type of round ship,[1] characterized by a flush-laid flat bottom at midships which gradually shifted to overlapped strakes near the posts. They were propelled by a single, large, rectangular sail. Typical seagoing cogs ranged from about 15 to 25 meters (49 to 82 ft) in length with a beam of 5 to 8 meters (16 to 26 ft) and were 40–200 tons burthen. Cogs were rarely as large as 300 tons, although a very small number were considerably larger, over 1,000 tons.[2][3][4][5] A rule of thumb for crew size was that one sailor, exclusive of any dedicated fighting men, was required for every 10 tons burthen of the cog, although this may generate a suggested crew size on the low side of Medieval practice.[6] Crews of up to 45 for civilian cogs are recorded, and 60 for a 240 ton cog being used for military transportation.[7]

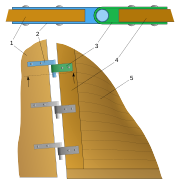

Cogs were typically constructed largely of oak, and had full lapstrake, or clinker, planking covering their sides, generally starting from the bilge strakes, with double-clenched iron nails for plank fastenings. At the stem, chases are formed; that is, in each case, the land of the lower strake is tapered to a feather edge at the end of the strake where it meets the stem or stern-post. This allows the end of the strake to be fastened to the apron with the outside of the planking mutually flush at that point and flush with the stem. This means that the boat's passage through the water will not tend to lift the ends of the planking away from the stem. Before the next plank is fitted, the face of the land on the lower strake is bevelled to suit the angle at which the next strake will lie in relation with it. This varies all along the land. The new strake is held in position on the preceding one before the fastening is done.[8][9]

The keel, or keelplank, was only slightly thicker than the adjacent garboards and had no rabbet. Both stem and stern-posts were straight and rather long, and connected to the keelplank through intermediate pieces called hooks. The lower plank hoods terminated in rabbets in the hooks and posts, but upper hoods were nailed to the exterior faces of the posts. Caulking was generally tarred moss that was inserted into curved grooves, covered with wooden laths, and secured by metal staples called sintels.[8] The cog-built structure would be completed with a stern-mounted, hanging, central rudder on a heavy stern-post, which was a uniquely northern development.[10] The single, thick, mast was set forward of amidships, stepped into the keelplank and equipped with a single large, rectangular, square-rigged sail.[11][9] The masts of larger vessels would be of composite construction.[12] Complicated systems of rigging were developed to support the mast and to operate the sail.[13] Cordage was usually hemp or flax[note 1] and the sail hemp-based canvas.[14] From the 13th century cogs would be decked, and larger vessels would be fitted with a stern castle, to afford more cargo space by keeping the crew and tiller up, out of the way; and to give the helmsman a better view.[15]

A cog, compared with the carvel-built vessels more traditional in the Mediterranean, was expensive and required specialist shipwrights. However, their simpler sail setup meant that cogs only required half the crew of similar sized vessels equipped with lateen sails, as were common in the Mediterranean.[16] A structural benefit of clinker construction is that it produces a vessel that can safely twist and flex around its long axis (running from bow to stern), which is an advantage in North Atlantic rollers, provided the vessel has a small overall displacement. A limitation of cogs is that they lack points to mount additional masts: at least some fore-and-aft sails are desirable for manoeuvrability but clinker-built cogs were effectively limited to a single sail.[17][18] This made them unhandy, limiting their ability to tack in harbour and making them very reliant on wind direction at the start of voyages.[17][19] The flat bottom permitted cogs to be readily beached and unloaded at low tide when quays were not available; a useful trait when purpose built jetties were not common.[11] Cogs were expected to have a working life of approximately 40 years.[4][note 2]

History[]

The classic cog, with a rear-mounted rudder, is first mentioned in 948 AD. These early cogs were influenced by the Norse knarr, which was the main trade vessel in northern Europe at the time, which used a steering oar. Cogs could carry more cargo than knarrs; the rudder made steering easier than did the steering oar of the knarr, especially for larger vessels; and cogs were cheaper to build.[15] The latter was due to the cog's use of sawn, rather than split, timber.[15] Fore and stern castles would be added for defense against pirates, or to enable the use of these vessels as warships.[20] The stern castle also afforded more cargo space below by keeping the crew and tiller up, out of the way.

Current archaeological evidence points to the Frisian coast or Western Jutland as the possible birthplace of this type of vessel. The transformation of the cog into a true seagoing trader came not only during the time of the intense trade between West and East, but also as a direct answer to the closure of the western entrance to the Limfjord. For centuries, the Limfjord in northern Jutland offered a fairly protected passage between the North Sea and the Baltic. Due to its unusual geographical conditions and strong currents, the passage was constantly filling with sand and was completely blocked by the early 12th century. This change produced new challenges. The larger ships, which could not be pulled across the sand bars, had to sail around the Jutland peninsula and circumnavigate the dangerous Cape Skagen to get to the Baltic.[21] This resulted in major modifications to old ship structures, which can be observed by analyzing the evolution of the earliest cog finds of Kollerup, Skagen, and Kolding. This caused a boom in the number of small cogs, and the need for spacious and seaworthy ships led to the development of the cog as the workhorse of the Hanseatic League.[21] It soon became the main cargo carrier in Atlantic and Baltic waters.[18][22]

Eventually, around the 14th century, the cog reached its structural limits, and larger or more seaworthy vessels needed to be of a different type. This was the hulk, which already existed but was much less common than the cog. There is no evidence that hulks descended from cogs, but it is clear that a lot of technological ideas were adapted between the two types.[10] The transition from cogs to hulks was not linear, according to some interpretations both vessels coexisted for many centuries but followed diverse lines of evolution.[23]

Archaeology[]

The most famous cog in existence today is the Bremen cog. It dates from the 1380s and was found in 1962; until then, cogs had only been known from medieval documents and seals. In 1990 the well-preserved remains of a Hanseatic cog were discovered in the estuary sediment of the Pärnu River in Estonia which has been dated to 1300.[24] In 2012, a cog dating from the early 15th century was discovered preserved from the keel up to the decks in the silt of the River IJssel in the city of Kampen, Netherlands.[25] During its excavation and recovery an intact brick dome oven and glazed tiles were found in the galley as well as a number of other artifacts.[26][27]

See also[]

Notes, citations and sources[]

Notes[]

Citations[]

- ^ Rose 2001, p. 28.

- ^ Rodger 2004, p. 62.

- ^ Madden 2014, p. 104.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cushway 2011, p. 24.

- ^ Sumption 1990, p. 178.

- ^ Sumption 1990, p. 177.

- ^ Lambert 2011, p. 199.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Runyan 2003, p. 61.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hutchinson 1994, p. 18–19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crumlin-Pedersen 2000.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Runyan 1994, p. 47.

- ^ Hutchinson 1994, p. 56.

- ^ Hutchinson 1994, p. 56–57.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hutchinson 1994, p. 57.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Runyan 1994, p. 48.

- ^ Runyan 1994, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Friel 1994, p. 184.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rodger 2004, p. 63.

- ^ Rodger 2004, p. 64.

- ^ McGrail 1981, p. 38.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hutchinson 1994, p. 72.

- ^ Bachrach & Bachrach 2017, p. 167.

- ^ Gardiner & Unger 1994.

- ^ Õun, Mati and Hanno Ojalo. 2015. 101 Eesti laeva. Tallinn, Kirjastus Varrak, page 12.

- ^ "Excavation, recovery and conservation of a 15th century Cog from the river IJssel near Kampen". Ruimte voor de Rivier IJsseldelta. Rijkswaterstaat. September 2015. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Ghose, Tia (17 February 2016). "Medieval Shipwreck Hauled from the Deep". Live Science. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ "Late Medieval Cog from Kampen". Medieval Histories. 21 February 2016. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

Sources[]

- Bachrach, Bernard S.; Bachrach, David S. (2017). Warfare in Medieval Europe c.400 – c.1453. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1138887664.

- Bass, George F. (1972). A History of Seafaring: Based on Underwater Archaeology. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-01077-3.

- Crumlin-Pedersen, Ole (2000). "To be or not to be a Cog: the Bremen Cog in Perspective". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 29 (2): 230–246. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2000.tb01454.x.

- Cushway, Graham (2011). Edward III and the War at Sea: The English Navy, 1327-1377. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843836216.

- Friel, Ian (1994). "Winds of Change? Ships and the Hundred Years War". In Curry, Anne (ed.). Arms, Armies, and Fortifications in the Hundred Years War. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. pp. 183–194. ISBN 0-85115-365-8.

- Gardiner, Robert; Unger, Richard W., eds. (August 1994). Cogs, Caravels and Galleons: The Sailing Ship, 1000-1650. Conway's History of the Ship. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0851775609.

- Hutchinson, Gillian (1994). Medieval Ships and Shipping. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses. ISBN 9780718501174.

- Lambert, Craig (2011). Shipping the Medieval Military: English Maritime Logistics in the Fourteenth Century. Warfare in History. 34. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843836544.

- McGrail, Sean (1981). Rafts, Boats and Ships. London: National Maritime Museum. ISBN 0-11-290312-6.

- Madden, Mollie Marie (2014). The Black Prince at War: The Anatomy of a Chevauchée (PDF) (PhD thesis). Minnesota: University of Minnesota.

- Prestwich, Michael (2007) [2005]. Plantagenet England 1225–1360. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199226870. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- Rodger, N.A.M. (2004). The Safeguard of the Sea. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0140297249.

- Rose, Susan (1997). "Battle of Sluys". In Grove, E. (ed.). Great Battles of the Royal Navy: As Commemorated in the Gunroom, Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth (illustrated [some in colour] ed.). London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 978-1854094179.

- Rose, Susan (2001). Medieval Naval Warfare 1000-1500. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1134553105.

- Runyan, Timothy (1994). "Cog as Warship". In Gardiner, Robert; Unger, Richard W (eds.). Cogs, Caravels and Galleons: the Sailing Ship from 1000–1650. Conway's History of the Ship. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 47–58. ISBN 978-0851775609. OCLC 932458210.

- Runyan, Timothy (2003). Hattendorf, John B.; Unger, Richard W. (eds.). War at Sea in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Warfare in History. 14. Woodbridge, Suffolk; Rochester, New York: Boydell Press. pp. 53–68. ISBN 978-0851159034.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1990). Trial by Battle. The Hundred Years' War. I. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571200955.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cogs (ships). |

- Merchant sailing ship types

- Sailing rigs and rigging

- Hanseatic League

- Medieval ships

- Tall ships