Cold War (1962–1979)

The Cold War (1962–1979) refers to the phase within the Cold War that spanned the period between the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis in late October 1962, through the détente period beginning in 1969, to the end of détente in the late 1970s.

The United States maintained its Cold War engagement with the Soviet Union during the period, despite internal preoccupations with the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the Civil Rights Movement and the opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War.

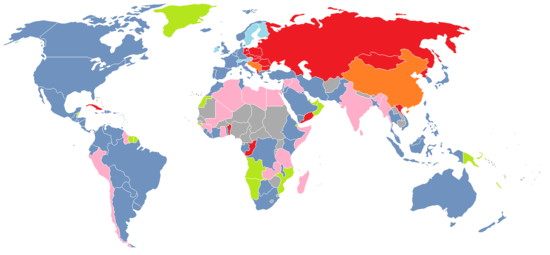

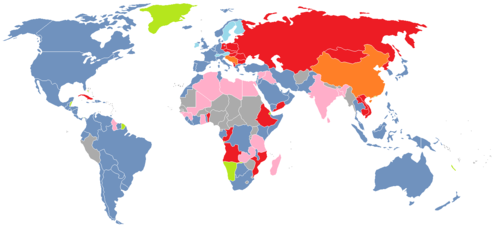

In 1968, Eastern Bloc member Czechoslovakia attempted the reforms of the Prague Spring and was subsequently invaded by the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact members, who reinstated the Soviet model. By 1973, the US had withdrawn from the Vietnam War. While communists gained power in some South East Asian countries, they were divided by the Sino-Soviet Split, with China moving closer to the Western camp, following US President Richard Nixon's visit to China. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Third World was increasingly divided between governments backed by the Soviets (such as Libya, Iraq, Syria, Egypt and South Yemen.) governments backed by NATO (such as Saudi Arabia), and a growing camp of non-aligned nations.

The Soviet and other Eastern Bloc economies continued to stagnate. Worldwide inflation occurred following the 1973 oil crisis.

Third World and non-alignment in the 1960s and 1970s[]

| Part of a series on |

| History of the Cold War |

|---|

|

Decolonization[]

Cold War politics were affected by decolonization in Africa, Asia, and to a limited extent, Latin America as well. The economic needs of emerging Third World states made them vulnerable to foreign influence and pressure.[1] The era was characterized by a proliferation of anti-colonial national liberation movements, backed predominantly by the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China.[2] The Soviet leadership took a keen interest in the affairs of the fledgling ex-colonies because it hoped the cultivation of socialist clients there would deny their economic and strategic resources to the West.[1] Eager to build its own global constituency, the People's Republic of China attempted to assume a leadership role among the decolonizing territories as well, appealing to its image as a non-white, non-European agrarian nation which too had suffered from the depredations of Western imperialism.[3] Both nations promoted global decolonization as an opportunity to redress the balance of the world against Western Europe and the United States, and claimed that the political and economic problems of colonized peoples made them naturally inclined towards socialism.[3]

Western fears of a conventional war with the communist bloc over the colonies soon shifted into fears of communist subversion and infiltration by proxy.[4] The great disparities of wealth in many of the colonies between the colonized indigenous population and the colonizers provided fertile ground for the adoption of socialist ideology among many anti-colonial parties.[5] This provided ammunition for Western propaganda which denounced many anti-colonial movements as being communist proxies.[2]

As pressure for decolonization mounted, the departing colonial regimes attempted to transfer power to moderate and stable local governments committed to continued economic and political ties with the West.[5] Political transitions were not always peaceful; for example, violence broke out in Anglophone Southern Cameroons due to an unpopular union with Francophone Cameroon following independence from those respective nations.[5] The Congo Crisis broke out with the dissolution of the Belgian Congo, after the new Congolese army mutinied against its Belgian officers, resulting in an exodus of the European population and plunging the territory into a civil war which raged throughout the mid-1960s.[5] Portugal attempted to actively resist decolonization and was forced to contend with nationalist insurgencies in all of its African colonies until 1975.[6] The presence of significant numbers of white settlers in Rhodesia complicated attempts at decolonization there, and the former actually issued a unilateral declaration of independence in 1965 to preempt an immediate transition to majority rule.[7] The breakaway white government retained power in Rhodesia until 1979, despite a United Nations embargo and a devastating civil war with two rival guerrilla factions backed by the Soviets and Chinese, respectively.[7]

Third World alliances[]

Some developing countries devised a strategy that turned the Cold War into what they called "creative confrontation" – playing off the Cold War participants to their own advantage while maintaining non-aligned status. The diplomatic policy of non-alignment regarded the Cold War as a tragic and frustrating facet of international affairs, obstructing the overriding task of consolidating fledgling states and their attempts to end economic backwardness, poverty, and disease. Non-alignment held that peaceful coexistence with the first-world and second-world nations was both preferable and possible. India's Jawaharlal Nehru saw neutralism as a means of forging a "third force" among non-aligned nations, much as France's Charles de Gaulle attempted to do in Europe in the 1960s. The Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser manoeuvres between the blocs in pursuit of his goals was one example of this.

The first such effort, the Asian Relations Conference, held in New Delhi in 1947, pledged support for all national movements against colonial rule and explored the basic problems of Asian peoples. Perhaps the most famous Third World conclave was the Bandung Conference of African and Asian nations in 1955 to discuss mutual interests and strategy, which ultimately led to the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961. The conference was attended by twenty-nine countries representing more than half the population of the world. As at New Delhi, anti-imperialism, economic development, and cultural cooperation were the principal topics. There was a strong push in the Third World to secure a voice in the councils of nations, especially the United Nations, and to receive recognition of their new sovereign status. Representatives of these new states were also extremely sensitive to slights and discriminations, particularly if they were based on race. In all the nations of the Third World, living standards were wretchedly low. Some, such as India, Nigeria, and Indonesia, were becoming regional powers, most were too small and poor to aspire to this status.

Initially having a roster of 51 members, the UN General Assembly had increased to 126 by 1970. The dominance of Western members dropped to 40% of the membership, with Afro-Asian states holding the balance of power. The ranks of the General Assembly swelled rapidly as former colonies won independence, thus forming a substantial voting bloc with members from Latin America. Anti-imperialist sentiment, reinforced by the communists, often translated into anti-Western positions, but the primary agenda among non-aligned countries was to secure passage of social and economic assistance measures. Superpower refusal to fund such programs has often undermined the effectiveness of the non-aligned coalition, however. The Bandung Conference symbolized continuing efforts to establish regional organizations designed to forge unity of policy and economic cooperation among Third World nations. The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was created in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1963 because African leaders believed that disunity played into the hands of the superpowers. The OAU was designed

- to promote the unity and solidarity of the African states; to coordinate and intensify the cooperation and efforts to achieve a better life for the peoples of Africa; to defend their sovereignty; to eradicate all forms of colonialism in Africa and to promote international cooperation...

The OAU required a policy of non-alignment from each of its 30 member states and spawned several subregional economic groups similar in concept to the European Common Market. The OAU has also pursued a policy of political cooperation with other Third World regional coalitions, especially with Arab countries.

Much of the frustration expressed by non-aligned nations stemmed from the vastly unequal relationship between rich and poor states. The resentment, strongest where key resources and local economies have been exploited by multinational Western corporations, has had a major impact on world events. The formation of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1960 reflected these concerns. OPEC devised a strategy of counter-penetration, whereby it hoped to make industrial economies that relied heavily on oil imports vulnerable to Third World pressures. Initially, the strategy had resounding success. Dwindling foreign aid from the United States and its allies, coupled with the West's pro-Israel policies, angered the Arab nations in OPEC. In 1973, the group quadrupled the price of crude oil. The sudden rise in the energy costs intensified inflation and recession in the West and underscored the interdependence of world societies. The next year the non-aligned bloc in the United Nations passed a resolution demanding the creation of a new international economic order in which resources, trade, and markets would be distributed fairly.

Non-aligned states forged still other forms of economic cooperation as leverage against the superpowers. OPEC, the OAU, and the Arab League had overlapping members, and in the 1970s the Arabs began extending huge financial assistance to African nations in an effort to reduce African economic dependence on the United States and the Soviet Union. However, the Arab League has been torn by dissension between authoritarian pro-Soviet states, such as Nasser's Egypt and Assad's Syria, and the aristocratic-monarchial (and generally pro-Western) regimes, such as Saudi Arabia and Oman. And while the OAU has witnessed some gains in African cooperation, its members were generally primarily interested in pursuing their own national interests rather than those of continental dimensions. At a 1977 Afro-Arab summit conference in Cairo, oil producers pledged $1.5 billion in aid to Africa. Recent divisions within OPEC have made concerted action more difficult. Nevertheless, the 1973 world oil shock provided dramatic evidence of the potential power of resource suppliers in dealing with the more developed world.

Cuban Revolution and Cuban Missile Crisis[]

The years between the Cuban Revolution in 1959 and the arms control treaties of the 1970s marked growing efforts for both the Soviet Union and the United States to keep control over their spheres of influence. U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson landed 22,000 troops in the Dominican Republic in 1965, claiming to prevent the emergence of another Cuban Revolution. While the period from 1962 until Détente had no incidents as dangerous as the Cuban Missile Crisis, there was an increasing loss of legitimacy and good will worldwide for both the major Cold War participants.

30 September Movement[]

The 30 September Movement was a self-proclaimed organization of Indonesian National Armed Forces members who, in the early hours of 1 October 1965, assassinated six Indonesian Army generals in an abortive coup d'état. Among those killed was Minister/Commander of the Army Lieutenant General Ahmad Yani. Future president Suharto, who was not targeted by the kidnappers, took command of the army, persuaded the soldiers occupying Jakarta's central square to surrender and oversaw the end of the coup. A smaller rebellion in central Java also collapsed. The army publicly blamed the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) for the coup attempt, and in October, mass killings of suspected communists began. In March 1966, Suharto, now in receipt of a document from Sukarno giving him authority to restore order, banned the PKI. A year later he replaced Sukarno as president, establishing the strongly anti-communist 'New Order regime.[8]

1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia[]

A period of political liberalization took place in 1968 in Eastern Bloc country Czechoslovakia called the Prague Spring. The event was spurred by several events, including economic reforms that addressed an early 1960s economic downturn.[9][10] In April, Czechoslovakian leader Alexander Dubček launched an "Action Program" of liberalizations, which included increasing freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom of movement, along with an economic emphasis on consumer goods, the possibility of a multiparty government and limiting the power of the secret police.[11][12] Initial reaction within the Eastern Bloc was mixed, with Hungary's János Kádár expressing support, while Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and others grew concerned about Dubček's reforms, which they feared might weaken the Eastern Bloc's position during the Cold War.[13][14] On August 3, representatives from the Soviet Union, East Germany, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Czechoslovakia met in Bratislava and signed the Bratislava Declaration, which declaration affirmed unshakable fidelity to Marxism-Leninism and proletarian internationalism and declared an implacable struggle against "bourgeois" ideology and all "anti-socialist" forces.[15]

On the night of August 20–21, 1968, Eastern Bloc armies from four Warsaw Pact countries – the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Poland and Hungary – invaded Czechoslovakia.[16][17] The invasion comported with the Brezhnev Doctrine, a policy of compelling Eastern Bloc states to subordinate national interests to those of the Bloc as a whole and the exercise of a Soviet right to intervene if an Eastern Bloc country appeared to shift towards capitalism.[18][19] The invasion was followed by a wave of emigration, including an estimated 70,000 Czechs initially fleeing, with the total eventually reaching 300,000.[20] In April 1969, Dubček was replaced as first secretary by Gustáv Husák, and a period of "normalization" began.[21] Husák reversed Dubček's reforms, purged the party of liberal members, dismissed opponents from public office, reinstated the power of the police authorities, sought to re-centralize the economy and re-instated the disallowance of political commentary in mainstream media and by persons not considered to have "full political trust".[22][23] The international image of the Soviet Union suffered considerably, especially among Western student movements inspired by the "New Left" and non-Aligned Movement states. Mao Zedong's People's Republic of China, for example, condemned both the Soviets and the Americans as imperialists.

Vietnam War[]

U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson landed 42,000 troops in the Dominican Republic in 1965 to prevent the emergence of "another Fidel Castro." More notable in 1965, however, was U.S. intervention in Southeast Asia. In 1965 Johnson stationed 22,000 troops in South Vietnam to prop up the faltering anticommunist regime. The South Vietnamese government had long been allied with the United States. The North Vietnamese under Ho Chi Minh were backed by the Soviet Union and China. North Vietnam, in turn, supported the National Liberation Front, which drew its ranks from the South Vietnamese working class and peasantry. Seeking to contain Communist expansion, Johnson increased the number of troops to 575,000 in 1968.

North Vietnam received Soviet approval for its war effort in 1959; the Soviet Union sent 15,000 military advisors and annual arms shipments worth $450 million to North Vietnam during the war, while China sent 320,000 troops and annual arms shipments worth $180 million.[24]

While the early years of the war had significant U.S. casualties, the administration assured the public that the war was winnable and would in the near future result in a U.S. victory. The U.S. public's faith in "the light at the end of the tunnel" was shattered on January 30, 1968, when the NLF mounted the Tet Offensive in South Vietnam. Although neither of these offensives accomplished any military objectives, the surprising capacity of an enemy to even launch such an offensive convinced many in the U.S. that victory was impossible.

A vocal and growing peace movement centered on college campuses became a prominent feature as the counter culture of the 1960s adopted a vocal anti-war position. Especially unpopular was the draft that threatened to send young men to fight in the jungles of Southeast Asia.

Elected in 1968, U.S. President Richard M. Nixon began a policy of slow disengagement from the war. The goal was to gradually build up the South Vietnamese Army so that it could fight the war on its own. This policy became the cornerstone of the so-called "Nixon Doctrine." As applied to Vietnam, the doctrine was called "Vietnamization." The goal of Vietnamization was to enable the South Vietnamese army to increasingly hold its own against the NLF and the North Vietnamese Army.

On October 10, 1969, Nixon ordered a squadron of 18 B-52s loaded with nuclear weapons to race to the border of Soviet airspace in order to convince the Soviet Union that he was capable of anything to end the Vietnam War.

The morality of U.S. conduct of the war continued to be an issue under the Nixon presidency. In 1969, it came to light that Lt. William Calley, a platoon leader in Vietnam, had led a massacre of Vietnamese civilians a year earlier. In 1970, Nixon ordered secret military incursions into Cambodia in order to destroy NLF sanctuaries bordering on South Vietnam.

The U.S. pulled its troops out of Vietnam in 1973, and the conflict finally ended in 1975 when the North Vietnamese took Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City. The war exacted a huge human cost in terms of fatalities (see Vietnam War casualties). 195,000–430,000 South Vietnamese civilians died in the war.[25][26] 50,000–65,000 North Vietnamese civilians died in the war.[25][27] The Army of the Republic of Vietnam lost between 171,331 and 220,357 men during the war.[25][28] The official US Department of Defense figure was 950,765 communist forces killed in Vietnam from 1965 to 1974. Defense Department officials concluded that these body-count figures need to be deflated by 30 percent. In addition, Guenter Lewy assumes that one-third of the reported "enemy" killed may have been civilians, concluding that the actual number of deaths of communist military forces was probably closer to 444,000.[25] Between 200,000 and 300,000 Cambodians,[29][30][31] about 35,000 Laotians,[32] and 58,220 U.S. service members also died in the conflict.[A 1]

Nixon Doctrine[]

By the last years of the Nixon administration, it had become clear that it was the Third World that remained the most volatile and dangerous source of world instability. Central to the Nixon-Kissinger policy toward the Third World was the effort to maintain a stable status quo without involving the United States too deeply in local disputes. In 1969 and 1970, in response to the height of the Vietnam War, the President laid out the elements of what became known as the Nixon Doctrine, by which the United States would "participate in the defense and development of allies and friends" but would leave the "basic responsibility" for the future of those "friends" to the nations themselves. The Nixon Doctrine signified a growing contempt by the U.S. government for the United Nations, where underdeveloped nations were gaining influence through their sheer numbers, and increasing support to authoritarian regimes attempting to withstand popular challenges from within.

In the 1970s, for example, the CIA poured substantial funds into Chile to help support the established government against a Marxist challenge. When the Marxist candidate for president, Salvador Allende, came to power through free elections, the United States began funneling more money to opposition forces to help "destabilize" the new government. In 1973, a U.S.-backed military junta seized power from Allende. The new, repressive regime of General Augusto Pinochet received warm approval and increased military and economic assistance from the United States as an anti-Communist ally. Democracy was finally re-established in Chile in 1989.

Sino–Soviet split[]

The People's Republic of China's Great Leap Forward and other policies based on agriculture instead of heavy industry challenged the Soviet-style socialism and the signs of the USSR's influence over the socialist countries. As "de-Stalinization" went forward in the Soviet Union, China's revolutionary founder, Mao Zedong, condemned the Soviets for "revisionism." The Chinese also were growing increasingly annoyed at being constantly in the number two role in the communist world. In the 1960s, an open split began to develop between the two powers; the tension lead to a series of border skirmishes along the Chinese-Soviet border.

The Sino-Soviet split had important ramifications in Southeast Asia. Despite having received substantial aid from China during their long wars, the Vietnamese communists aligned themselves with the Soviet Union against China. The Khmer Rouge had taken control of Cambodia in 1975 and became one of the most brutal regimes in world history. The newly unified Vietnam and the Khmer regime had poor relations from the outset as the Khmer Rouge began massacring ethnic Vietnamese in Cambodia, and then launched raiding parties into Vietnam. The Khmer Rouge allied itself with China, but this was not enough to prevent the Vietnamese from invading them and destroying the regime in 1979. While unable to save their Cambodian allies, the Chinese did respond to the Vietnamese by invading the north of Vietnam on a punitive expedition later in that year. After a few months of heavy fighting and casualties on both sides, the Chinese announced the operation was complete and withdrew, ending the fighting.

The United States played only a minor role in these events, unwilling to get involved in the region after its debacle in Vietnam. The extremely visible disintegration of the communist bloc played an important role in the easing of Sino-American tensions and in the progress towards East-West Détente.

Détente and changing alliance[]

In the course of the 1960s and 1970s, Cold War participants struggled to adjust to a new, more complicated pattern of international relations in which the world was no longer divided into two clearly opposed blocs. The Soviet Union achieved rough nuclear parity with the United States. From the beginning of the post-war period, Western Europe and Japan rapidly recovered from the destruction of World War II and sustained strong economic growth through the 1950s and 1960s, with per capita GDPs approaching those of the United States, while Eastern Bloc economies stagnated.[38] China, Japan, and Western Europe; the increasing nationalism of the Third World, and the growing disunity within the communist alliance all augured a new multipolar international structure. Moreover, the 1973 world oil shock created a dramatic shift in the economic fortunes of the superpowers. The rapid increase in the price of oil devastated the U.S. economy leading to "stagflation" and slow growth.

Détente had both strategic and economic benefits for both sides of the Cold War, buoyed by their common interest in trying to check the further spread and proliferation of nuclear weapons. President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev signed the SALT I treaty to limit the development of strategic weapons. Arms control enabled both superpowers to slow the spiraling increases in their bloated defense budgets. At the same time, divided Europe began to pursue closer relations. The Ostpolitik of German chancellor Willy Brandt lead to the recognition of East Germany.

Cooperation on the Helsinki Accords led to several agreements on politics, economics and human rights. A series of arms control agreements such as SALT I and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty were created to limit the development of strategic weapons and slow the arms race. There was also a rapprochement between China and the United States. The People's Republic of China joined the United Nations, and trade and cultural ties were initiated, most notably Nixon's groundbreaking trip to China in 1972.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union concluded friendship and cooperation treaties with several states in the noncommunist world, especially among Third World and Non-Aligned Movement states.

During Détente, competition continued, especially in the Middle East and southern and eastern Africa. The two nations continued to compete with each other for influence in the resource-rich Third World. There was also increasing criticism of U.S. support for the Suharto regime in Indonesia, Augusto Pinochet's regime in Chile, and Mobuto Sese Seko's regime in Zaire.

The war in Vietnam and the Watergate crisis shattered confidence in the presidency. International frustrations, including the fall of South Vietnam in 1975, the hostage crisis in Iran from 1979-1981, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the growth of international terrorism, and the acceleration of the arms race raised fears over the country's foreign policy. The energy crisis, unemployment, and inflation, derided as "stagflation," raised fundamental questions over the future of American prosperity.

At the same time, the oil-rich USSR benefited immensely, and the influx of oil wealth helped disguise the many systemic flaws in the Soviet economy. At the same time, the entire Eastern Bloc continued to experience massive stagnation,[38][39] consumer goods shortfalls in shortage economies,[40][41] developmental stagnation[42] and large housing quantity and quality shortfalls.[43]

Culture and media[]

The preoccupation of Cold War themes in popular culture continued during the 1960s and 1970s. One of the better-known films of the period was the 1964 black comedy Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb directed by Stanley Kubrick and starring Peter Sellers. In the film, a mad United States general overrides the President's authority and orders a nuclear air strike on the Soviet Union. The film became a hit and today remains a classic.

In the United Kingdom, meanwhile, The War Game, a BBC television film written, directed, and produced by Peter Watkins was a Cold War piece of a darker nature. The film, depicting the impact of Soviet nuclear attack on England, caused dismay within both the BBC and in government. It was originally scheduled to air on August 6, 1966 (the anniversary of the Hiroshima attack) but was not transmitted until 1985.

In the 2011 superhero film, X-Men: First Class, the Cold War is portrayed to be controlled by a group of mutants that call themselves the Hell Fire Club.

In the summer of 1976, a mysterious and seemingly very powerful signal began infiltrating radio receivers around the globe. It has a signature 'knocking' sound when heard, and because the origin of this powerful signal was somewhere in the Soviet Union, the signal was given the nickname Russian Woodpecker. Many amateur radio listeners believed it to be part of the Soviet Unions over-the-horizon radar, however the Soviets denied they had anything to do with such signal. Between 1976 and 1989, the signal would come and go on many occasions and was most prominent on the shortwave radio bands. It was not until the end of the Cold War that the Russians admitted these radar pings were indeed that of Duga, an advanced over-the-horizon radar system.

The 2004 video game Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater is set in 1964 and deals heavily with the themes of nuclear deterrence, covert operations, and the Cold War.

The 2010 video game Call of Duty: Black Ops is set during this period of the Cold War.

Significant documents[]

- Partial or Limited Test Ban Treaty (PTBT/LTBT): 1963. Also put forth by Kennedy; banned nuclear tests in the atmosphere, underwater and in space. However, neither France nor China (both Nuclear Weapon States) signed.

- Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT): 1968. Established the U.S., USSR, UK, France, and China as five "Nuclear-Weapon States". Non-Nuclear Weapon states were prohibited from (among other things) possessing, manufacturing, or acquiring nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices. All 187 signatories were committed to the goal of (eventual) nuclear disarmament.

- Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM): 1972. Entered into between the U.S. and USSR to limit the anti-ballistic missile (ABM) systems used in defending areas against missile-delivered nuclear weapons; ended by the U.S. in 2002.

- Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties I & II (SALT I & II): 1972 / 1979. Limited the growth of U.S. and Soviet missile arsenals.

- Prevention of Nuclear War Agreement: 1973. Committed the U.S. and USSR to consult with one another during conditions of nuclear confrontation.

See also[]

- History of the Soviet Union (1953–1964)

- History of the Soviet Union (1964–1982)

- History of the United States (1964–1980)

- Indonesian killings of 1965–1966

- Timeline of Events in the Cold War

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- Vietnam War

- Prague Spring

- Détente

- Operation Neptune (Espionage)

- Re-education camp (Vietnam)

- Vietnamese boat people

Notes[]

- ^ The figures of 58,220 and 303,644 for U.S. deaths and wounded come from the Department of Defense Statistical Information Analysis Division (SIAD), Defense Manpower Data Center, as well as from a Department of Veterans fact sheet dated May 2010[33] the CRS (Congressional Research Service) Report for Congress, American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics, dated 26 February 2010,[34] and the book Crucible Vietnam: Memoir of an Infantry Lieutenant.[35] Some other sources give different figures (e.g. the 2005/2006 documentary Heart of Darkness: The Vietnam War Chronicles 1945–1975 cited elsewhere in this article gives a figure of 58,159 U.S. deaths,[36] and the 2007 book Vietnam Sons gives a figure of 58,226)[37]

Citations[]

- ^ a b Campbell, Kurt (1986). Soviet Policy Towards South Africa. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. pp. 129–131. ISBN 978-1349081677.

- ^ a b Sellström, Tor (2002). Sweden and National Liberation in Southern Africa: Vol. 2 : Solidarity and assistance, 1970–1994. Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute. pp. 30–32. ISBN 978-91-7106-448-6.

- ^ a b Friedman, Jeremy (2015). Shadow Cold War: The Sino-Soviet Competition for the Third World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 5, 149–157. ISBN 978-1-4696-2376-4.

- ^ Berridge, G.R. (1992). South Africa, the Colonial Powers and African Defence: The Rise and Fall of the White Entente, 1948–60. Basingstoke: Palgrave Books. pp. 1–16, 163–164. ISBN 978-0333563519.

- ^ a b c d Percox, David (2004). Britain, Kenya and the Cold War: Imperial Defence, Colonial Security and Decolonisation. London: Taurus Academic Studies. pp. 31–32, 160, 185. ISBN 978-1848859661.

- ^ Derluguian, Georgi (1997). Morier-Genoud, Eric (ed.). Sure Road? Nationalisms in Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. pp. 81–95. ISBN 978-9004222618.

- ^ a b Dowden, Richard (2010). Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles. Portobello Books. pp. 134–138. ISBN 978-1-58648-753-9.

- ^ Ricklefs 2008, pp. 438–442, 448–451 & 457

- ^ "Photius.com, (info from CIA world Factbook)". Photius Coutsoukis. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ Williams 1997, p. 5

- ^ Ello (ed.), Paul (April 1968). Control Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, "Action Plan of the (Prague, April 1968)" in Dubcek's Blueprint for Freedom: His original documents leading to the invasion of Czechoslovakia. William Kimber & Co. 1968, pp 32, 54

- ^ Von Geldern, James; Siegelbaum, Lewis. "The Soviet-led Intervention in Czechoslovakia". Soviethistory.org. Archived from the original on 2009-08-17. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ^ "Document #81: Transcript of Leonid Brezhnev's Telephone Conversation with Alexander Dubček, August 13, 1968". The Prague Spring '68. The Prague Spring Foundation. 1998. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ Navrátil 2006, pp. 36 & 172–181

- ^ Navrátil 2006, pp. 326–329

- ^ Ouimet, Matthew (2003). The Rise and Fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet Foreign Policy. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London. pp. 34–35.

- ^ "Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia". Military. GlobalSecurity.org. 2005-04-27. Retrieved 2007-01-19.

- ^ Grenville 2005, p. 780

- ^ Chafetz, Glenn (1993-04-30). Gorbachev, Reform, and the Brezhnev Doctrine: Soviet Policy Toward Eastern Europe, 1985–1990. Praeger Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 0-275-94484-0.

- ^ Čulík, Jan. "Den, kdy tanky zlikvidovaly české sny Pražského jara". Britské Listy. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ Williams 1997, p. xi

- ^ Goertz 1995, pp. 154–157

- ^ Williams 1997, p. 164

- ^ Qiang Zhai, China and the Vietnam Wars, 1950–1975 (University of North Carolina Press, 2000), p135; Gen. Oleg Sarin and Col. Lev Dvoretsky, Alien Wars: The Soviet Union's Aggressions Against the World, 1919 to 1989 (Presidio Press, 1996), pp93-4.

- ^ a b c d Lewy, Guenter (1978). America in Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press. Appendix 1, pp.450–453

- ^ Thayer, Thomas C (1985). War Without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam. Boulder: Westview Press. Ch. 12.

- ^ Wiesner, Louis A. (1988). Victims and Survivors Displaced Persons and Other War Victims in Viet-Nam. New York: Greenwood Press. p.310

- ^ Thayer, Thomas C (1985). War Without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam. Boulder: Westview Press. p.106.

- ^ Marek Sliwinski, Le Génocide Khmer Rouge: Une Analyse Démographique (L'Harmattan, 1995)

- ^ Heuveline, Patrick (2001). "The Demographic Analysis of Mortality in Cambodia." In Forced Migration and Mortality, eds. Holly E. Reed and Charles B. Keely. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

- ^ Banister, Judith, and Paige Johnson (1993). "After the Nightmare: The Population of Cambodia." In Genocide and Democracy in Cambodia: The Khmer Rouge, the United Nations and the International Community, ed. Ben Kiernan. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies.

- ^ T. Lomperis, From People's War to People's Rule, (1996), estimates 35,000 total.

- ^ America's Wars (factsheet) (PDF) (Report). Department of Veterans Affairs. 26 February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2014. Retrieved May 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ^ Anne Leland; Mari–Jana "M-J" Oboroceanu (26 February 2010). American War and Military Operations: Casualties: Lists and Statistics (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service.

- ^ Lawrence 2009, pp. 65, 107, 154, 217

- ^ Aaron Ulrich (editor); Edward FeuerHerd (producer and director) (2005–2006). Heart of Darkness: The Vietnam War Chronicles 1945–1975 (Documentary; box set, Color, Dolby, DVD-Video, full-screen, NTSC, Vision Software). Koch Vision. Event occurs at 321 minutes. ISBN 1-4172-2920-9.

- ^ Kueter, Dale. Vietnam Sons: For Some, the War Never Ended. AuthorHouse (March 21, 2007). ISBN 978-1425969318

- ^ a b Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 16

- ^ Maddison 2006, p. 185

- ^ Dale 2005, p. 85

- ^ Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 474

- ^ Frucht 2003, p. 382

- ^ Sillince 1990, pp. 1–40

References[]

- Ball, S. J. The Cold War: An International History, 1947–1991 (1998). British perspective

- Beschloss, Michael, and Strobe Talbott. At the Highest Levels:The Inside Story of the End of the Cold War (1993)

- Bialer, Seweryn and Michael Mandelbaum, eds. Gorbachev's Russia and American Foreign Policy (1988).

- Dale, Gareth (2005), Popular Protest in East Germany, 1945–1989: Judgements on the Street, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7146-5408-9

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (2007), A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-36626-7

- Brzezinski, Zbigniew. Power and Principle: Memoirs of the National Security Adviser, 1977–1981 (1983);

- Edmonds, Robin. Soviet Foreign Policy: The Brezhnev Years (1983)

- Gaddis, John Lewis. The Cold War: A New History (2005)

- Long Peace: Inquiries into the History of the Cold War (1987)

- Frucht, Richard C. (2003), Encyclopedia of Eastern Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism, Taylor & Francis Group, ISBN 0-203-80109-1

- Gaddis, John Lewis. * LaFeber, Walter. America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–1992 7th ed. (1993)

- Gaddis, John Lewis. The United States and the End of the Cold War: Implications, Reconsiderations, Provocations (1992)

- Garthoff, Raymond. The Great Transition:American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War (1994)

- Goertz, Gary (1995), Contexts of International Politics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-46972-4

- Grenville, John Ashley Soames (2005), A History of the World from the 20th to the 21st Century, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-28954-8

- Hardt, John Pearce; Kaufman, Richard F. (1995), East-Central European Economies in Transition, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 1-56324-612-0

- Hogan, Michael ed. The End of the Cold War. Its Meaning and Implications (1992) articles from Diplomatic History online at JSTOR

- Kyvig, David ed. Reagan and the World (1990)

- Lawrence, A.T. (2009). Crucible Vietnam: Memoir of an Infantry Lieutenant. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5470-9.

- Maddison, Angus (2006), The world economy, OECD Publishing, ISBN 92-64-02261-9

- Mower, A. Glenn Jr. Human Rights and American Foreign Policy: The Carter and Reagan Experiences ( 1987),

- Navrátil, Jaromír (2006), The Prague Spring 1968: A National Security Archive Document Reader (National Security Archive Cold War Readers), Central European University Press, ISBN 963-7326-67-7

- Matlock, Jack F. Autopsy on an Empire (1995) by US ambassador to Moscow

- Powaski, Ronald E. The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917–1991 (1998)

- Ricklefs, M.C. (2008) [1981]. A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300 (4th ed.). London: MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-54685-1.

- Shultz, George P. Turmoil and Triumph: My Years as Secretary of State (1993).

- Sivachev, Nikolai and Nikolai Yakolev, Russia and the United States (1979), by Soviet historians

- Sillince, John (1990), Housing policies in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-02134-0

- Smith, Gaddis. Morality, Reason and Power:American Diplomacy in the Carter Years (1986).

- Williams, Kieran (1997), The Prague Spring and its Aftermath: Czechoslovak Politics, 1968–1970, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-58803-0

- Cold War by period

- 1962 in international relations

- 1963 in international relations

- 1964 in international relations

- 1965 in international relations

- 1966 in international relations

- 1967 in international relations

- 1968 in international relations

- 1969 in international relations

- 1970 in international relations

- 1971 in international relations

- 1972 in international relations

- 1973 in international relations

- 1974 in international relations

- 1975 in international relations

- 1976 in international relations

- 1977 in international relations

- 1978 in international relations

- 1979 in international relations