Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership

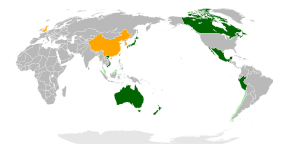

Ratifiers (dark green) Other Signatories (light green) Applicants (orange) | |

| Type | Trade agreement |

|---|---|

| Signed | 8 March 2018 |

| Location | Santiago, Chile |

| Sealed | 23 January 2018 |

| Effective | 30 December 2018 |

| Condition | 60 days after ratification by 50% of the signatories, or after six signatories have ratified |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

| Depositary | Government of New Zealand[2] |

| Languages | English (prevailing in the case of conflict or divergence), Spanish and French[2] |

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), also known as TPP11 or TPP-11,[3][4][5][6] is a trade agreement among Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam. It evolved from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which never entered into force due to the withdrawal of the United States. The eleven signatories have combined economies representing 13.4 percent of global gross domestic product, at approximately US$13.5 trillion, making the CPTPP one of the world's largest free-trade areas by GDP, along with the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, the European Single Market,[7] and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

The TPP had been signed on 4 February 2016, but never entered into force, as the U.S. withdrew from the agreement soon after the election of president Donald Trump.[8] All other TPP signatories agreed in May 2017 to revive the agreement,[9][10] with Japan widely reported as taking the leading role in place of the U.S.[11][12][13][14] In January 2018, the CPTPP was created as a succeeding agreement, retaining two-thirds of its predecessor's provisions; 22 measures favored by the US, but contested by other signatories, were suspended, while the threshold for enactment was lowered so as not to require American accession.[15][16]

The formal signing ceremony was held on 8 March 2018 in Santiago, Chile.[17][18] The agreement specifies that its provisions enter into effect 60 days after ratification by at least half the signatories (six of the eleven participating countries).[15] Australia was the sixth nation to ratify the agreement, on 31 October 2018, and it subsequently came into force for the initial six ratifying countries on 30 December 2018.[19]

The chapter on state-owned enterprises (SOEs) is unchanged, requiring signatories to share information about SOEs with each other, with the intent of engaging with the issue of state intervention in markets. It includes the most detailed standards for intellectual property of any trade agreement, as well as protections against intellectual property theft against corporations operating abroad.[16]

Negotiations[]

During the round of negotiations held concurrently with the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum in Vietnam in November 2017, Canadian PM Justin Trudeau refused to sign the agreement in principle, stating reservations about the provisions on culture and automotives. Media outlets in Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, which strongly supported quick movement on a deal, strongly criticized what they portrayed as Canadian sabotage.[20]

Canada insisted that cultural and language rights, specifically related to its French-speaking minority, be protected.[21]

However, Canada's major reservation was a conflict between the percentage of a vehicle that must originate in a CPTPP member nation to enter tariff-free, which was 45% under the original TPP language and 62.5% under the NAFTA agreement. Japan, which is a major automobile part exporter, strongly supports lower requirements.[20] In January 2018, Canada announced that it would sign the CPTPP after obtaining binding side letters on culture with every other CPTPP member country, as well as bilateral agreements with Japan, Malaysia, and Australia related to non-tariff barriers. Canada's sharply criticized increasing the percentages of automobile parts that may be imported tariff-free, noting that the United States was moving in the opposite direction by demanding stricter importation standards in the ongoing NAFTA renegotiation.[21]

In February 2019, Canada's Jim Carr, Minister of International Trade Diversification, delivered a keynote address at a seminar concerning CPTPP - Expanding Your Business Horizons, reaching out to businesses stating the utilisation of the agreement provides a bridge that will enable people, goods and services to be shared more easily.[22]

Ratifications[]

On 28 June 2018, Mexico became the first country to finish its domestic ratification procedure of the CPTPP, with President Enrique Peña Nieto stating, "With this new generation agreement, Mexico diversifies its economic relations with the world and demonstrates its commitment to openness and free trade."[23][24]

On 6 July 2018, Japan became the second country to ratify the agreement.[25][26]

On 19 July 2018, Singapore became the third country to ratify the agreement and deposit its instrument of ratification.[27][28]

On 17 October 2018, the Australian Federal Parliament passed relevant legislation through the Senate.[29][30][31] The official ratification was deposited on 31 October 2018.[citation needed][6] This two-week gap made Australia the sixth signatory to deposit its ratification of the agreement, and it came into force 60 days later.

On 25 October 2018, New Zealand ratified the CPTPP, increasing the number of countries that had formally ratified the agreement to four.[32]

Also on 25 October 2018, Canada passed[33] and was granted royal assent on[34] the enabling legislation. The official ratification was deposited on 29 October 2018.[35][36][37]

On 2 November 2018, the CPTPP and related documents were submitted to the National Assembly of Vietnam for ratification.[38] On 12 November 2018, the National Assembly passed a resolution unanimously ratifying the CPTPP.[39] The Vietnamese government officially notified New Zealand of its ratification on 15 November 2018.[40]

On 17 April 2019, the CTPPP was approved by the Chamber of Deputies of Chile. The final round of approval in the Senate was scheduled for November 2019, after being approved by its Commission of Constitution. However, one of the demands of the 2019 Chilean protests was the rejection of the treaty,[41][dubious ] so the Senate decided to suspend the session regarding the CTPPP on 11 November 2019.

On 14 July 2021, the CTPPP was approved by the Congress of the Republic of Peru. The official ratification was deposited on 21 July 2021.[1]

An overview of the legislative process in selected states is shown below:

| Signatory | Signature[17] | Institution | Conclusion date | AB | Deposited | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 March 2018 | Senate | 24 April 2018 | 73 | 24 | 28 June 2018[23][24] | [42] | ||

| Presidential Assent | 23 May 2018 | Granted | ||||||

| 8 March 2018 | House of Representatives | 18 May 2018 | Majority approval (Standing vote) | 6 July 2018[25] | [43] | |||

| House of Councillors | 13 June 2018 | 168 | 69 | [44] | ||||

| 8 March 2018 | No parliamentary approval required | 19 July 2018[27] | [45] | |||||

| 8 March 2018 | House of Representatives | 24 October 2018 | 111 | 8 | 25 October 2018[32] | [46][47] | ||

| Royal assent | 25 October 2018 | Granted | [46] | |||||

| 8 March 2018 | House of Commons | 16 October 2018 | 236 | 44 | 1 | 29 October 2018[35][36] | [48] | |

| Senate | 25 October 2018 | Majority approval (Voice vote) | [33] | |||||

| Royal assent | 25 October 2018 | Granted | [34][37] | |||||

| 8 March 2018 | House of Representatives | 19 September 2018 | Majority approval (Standing vote) | 31 October 2018[6] | [49][30][31] | |||

| Senate | 17 October 2018 | 33 | 15 | [50][30][31] | ||||

| Royal assent | 19 October 2018 | Granted | [30][31] | |||||

| 8 March 2018 | National Assembly | 12 November 2018 | 469 | 0 | 16 | 15 November 2018[40] | [51][52] | |

| 8 March 2018 | Congress | 14 July 2021 | 97 | 0 | 9 | 21 July 2021[53] | [1][54] | |

| 8 March 2018 | Chamber of Deputies | 17 April 2019 | 77 | 68 | 2 | [55][56] | ||

| Senate | Under deliberation | |||||||

Entry into force[]

The agreement came into effect 60 days after ratification and deposit of accession documents by at least half the signatories (six of the eleven signatories).[15] Australia was the sixth country to ratify the agreement, which was deposited with New Zealand on 31 October 2018, and consequently the agreement came into force between Australia, Canada, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, and Singapore on 30 December 2018.[19]

On 1 January 2019, Australia, Canada, Mexico, New Zealand, and Singapore implemented a second round of tariff cuts. Japan's second tariff cut took place on 1 April 2019.[37]

On 15 November 2018, Vietnam deposited the accession documents, and the agreement entered into force in Vietnam on 14 January 2019.[37][40][57]

On 21 July 2021, Peru deposited the accession documents, and the agreement entered into force in Peru on 19 September 2021.[1]

CPTPP Commission[]

The CPTPP Commission is the decision-making body of the CPTPP, which was established when the CPTPP entered into force on 30 December 2018.[58]

1st CPTPP Commission (2019)

Representatives from the eleven CPTPP signatories participated in the 1st CPTPP Commission meeting held in Tokyo on 19 January 2019,[59] which decided:

- A decision about the chairing and administrative arrangements for the commission and special transitional arrangements for 2019;[60]

- A decision to establish the accession process for interested economies to join the CPTPP;[61] Annex[62]

- A decision to create rules of procedure and a code of conduct for disputes involving Parties to the;[63] Annex;[64] Annex I[65]

- A decision to create a code of conduct for investor-State dispute settlement.;[66] Annex[67]* Members of the CPTPP Commission also issued a joint ministerial statement on 19 January 2019.[68]

2nd CPTPP Commission (2019)

2nd CPTPP Commission meeting was held on 9 October 2019 in Auckland, New Zealand. Alongside the commission, the following Committees met for the first time in Auckland: Trade in Goods; Rules of Origin; Agricultural Trade; Technical Barriers to Trade; Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures; Small and Medium Sized Enterprises; State Owned Enterprises; Development; Cooperation and Capacity Building; Competitiveness and Business Facilitation; Environment; and the Labour Council. The Commission adopted two formal decisions, (i) on its Rules of Procedure under Article 27.4 and (ii) to establish a Roster of Panel Chairs as provided for under Article 28.11.[69][70]

3rd CPTPP Commission (2020)

3rd CPTPP Commission meeting was held virtually and hosted by Mexico on 5 August 2020.[71]

4th CPTPP Commission (2021)

4th CPTPP Commission meeting was held virtually and hosted by Japan on 2 June 2021.[72] The Commission decided to move forward with the application of the United Kingdom as an aspirant economy.

5th CPTPP Commission (2021)

5th CPTPP Commission meeting was held virtually and hosted by Japan on 1 September 2021.[73] The Commission decided to establish a Committee on Electronic Commerce composed of government representatives of each Party.

6th CPTPP Commission (2022)

Singapore will host the next CPTPP Commission in 2022.[73]

Enlargement[]

CPTPP rules require all eleven signatories to agree to the admission of additional members.[74]

Current applicants[]

United Kingdom[]

On 1 February 2021, the UK formally applied to join CPTPP.[75] The UK is the first non-founding country to apply to join the CPTPP. If successful, the UK would become the second largest CPTPP economy, after Japan.[76] Japan had expressed support for the UK's potential entry into CPTPP in 2018,[77] and as 4th CPTPP Commission (2021) chair, Japan’s minister in charge of negotiations on the trade pact, Yasutoshi Nishimura, expressed hope on Twitter that Britain will "demonstrate its strong determination to fully comply with high-standard obligations" of the free trade accord, and mentioned that "I believe that the UK’s accession request will have a great potential to expand the high-standard rules beyond the Asia-Pacific."[78]

In January 2018, the government of the United Kingdom stated it was exploring membership of the CPTPP to stimulate exports after Brexit and has held informal discussions with several of the members.[79] The country has an overseas territory, the Pitcairn Islands, in the Pacific Ocean.[80] In October 2018, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said he would welcome the United Kingdom joining the partnership post-Brexit.[81] In a joint Telegraph article with Simon Birmingham, David Parker, and Chan Chun Sing, the trade ministers of Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore, UK Secretary of State for Trade, Liz Truss, expressed the United Kingdom's intent to join the CPTPP.[82]

The UK Department for Trade's chief negotiator Crawford Falconer helped lead the New Zealand negotiations for the predecessor Trans-Pacific Partnership before leaving the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade in 2012.[83]

In June 2020, the government of the United Kingdom issued a policy paper[84] reaffirming the UK's position on accession to the CPTPP. There were three reasons given:

- Securing increased trade and investment opportunities that will help the UK economy overcome the unprecedented challenge posed by coronavirus. Joining CPTPP would open up new opportunities for UK exporters in strategically important sectors and helping to support an industrial revival in the UK.

- Helping the United Kingdom diversify trading links and supply chains, and in doing so increasing economic security at a time of heightened uncertainty and disruption in the world.

- Assisting the UK's future place in the world and advancing the UK's longer-term interests. CPTPP membership is an important part of our strategy to place the UK at the centre of a modern, progressive network of free trade agreements with dynamic economies. Doing so would turn the UK into a global hub for businesses and investors wanting to trade with the rest of the world.

Furthermore, the UK government stated that in 2019, each region and nation of the UK exported at least £1 billion ($1.25 billion) worth of goods to CPTPP member countries.[85] The UK government also highlighted that UK companies held close to £98 billion worth of investments in CPTPP countries in 2018[86] and that in 2019, the UK did more than £110 billion ($137 billion) worth of trade with countries in the CPTPP free trade area.[87] In December 2020 the UK's Secretary of State for Trade Liz Truss further expressed her desire for the UK to formally apply in early 2021.[88] In a speech, held on January 20, 2021, Truss announced the UK planned to submit an application for participation "shortly".[89] In October 2020 the United Kingdom and Japan already signed the UK-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement which was a roll over of the agreement between the EU and Japan.

The UK government has not produced an impact assessment that explains or quantifies the benefits it expects for the UK economy from accession to CPTPP.[90] As such, it is a matter of dispute in UK as to whether accession is worth pursuing for economic reasons.[91] Farmer, environmental and consumer groups have all raised concerns that the UK government will need to agree to lowering standards on pesticides, pig welfare and food labelling.[92] These concerns have also been raised by the Scottish government.[93]

In June 2021, the CPTPP states agreed to open accession talks. A working group is expected to be established to discuss tariffs and rules governing investment and trade. The UK is not expected to accede to the CPTPP until 2022 at the earliest.[94]

China[]

In May 2020, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang said that China was willing to consider joining CPTPP.[95] Meanwhile, Chinese President Xi Jinping said at an Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in November 2020 that China would “actively consider” joining CPTPP.

Trade experts have interpreted China’s position as having a “different strategic significance” from an actual intent to join. Their analysis is that China aims to keep the US from joining and delay the CPTPP’s expansion into a larger-scale framework. James Kane, a researcher with the UK’s Institute for Government, recently told Reuters that CPTPP has a political purpose, as well as an economic one, in the sense that it aims to present a bloc as a common front — representing 13.5% of the global market economy — in order to create new rules countering China’s practices of disrupting global trade norms, including its subsidies to state enterprises. Analysts also predicted that existing members would very likely veto a Chinese application to join CPTPP.[74]

On 16 September 2021, China formally applied to join CPTPP.[96]

Australian Trade Minister Dan Tehan has indicated that Australia will oppose China’s application until China halts trade strikes against Australian exports and resumes minister-to-minister contacts with the Australian government. Also, Australia has lodged disputes against China in the WTO on restrictions imposed by China on exports of barley and wine.[97]

Taiwan[]

Taiwan applied to join CPTPP on 22 September 2021.[98]

It had previously expressed interest to join TPP in 2016.[99] After TPP’s evolution to CPTPP in 2018, Taiwan indicated its will to continue efforts to join CPTPP.[100] In December 2020, the Taiwanese government stated that it would submit an application to join CPTPP following the conclusion of informal consultations with existing members.[101] In February 2021 again, Taiwan indicated its will to apply to join CPTPP at an appropriate time.[102] A few days after China submitted its request to join the CPTPP, Taiwan sent its own request to join the CPTPP, a move that has been one of the main policy objectives of Tsai's government. [103]

Potential applicants[]

United States[]

On 25 January 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump in an interview announced his interest in possibly rejoining the TPP if it were a "substantially better deal" for the United States. He had withdrawn the U.S. from the original agreement in January 2017.[104] On 12 April 2018, he told the White House National Economic Council Director Larry Kudlow and U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer to look into joining CPTPP.[105] U.S. Wheat Associates President Vince Peterson had said in December 2018 that American wheat exporters could face an “imminent collapse” in their 53% market share in Japan due to CPTPP. Peterson added, “Our competitors in Australia and Canada will now benefit from those [CPTPP] provisions, as US farmers watch helplessly.” The National Cattlemen's Beef Association stated that exports of beef to Japan, America's largest export market, would be at a serious disadvantage to Australian exporters as their tariffs on exports to Japan would be cut by 27.5% during the first year of CPTPP.[106][107]

In December 2020, a bipartisan group of U.S. policy experts, Richard L. Armitage and Joseph S. Nye Jr., called for Washington to join the CPTPP.[108][109]

Philippines[]

The Philippines previously wanted to join the TPP in 2016 under Benigno Aquino, who said that the country stood to gain from becoming a member of the trade pact.[110]

South Korea[]

In January 2021, South Korea’s Moon administration announced it would seek to join CPTPP.[111] The country will examine sanitary and phytosanitary measures, fisheries subsidies, digital trade and guidelines related to state-run enterprises to meet the requirements that CPTPP has suggested. Japan’s objections to recent proposals to invite South Korea as an observer to the G7 indicate the bilateral relationship will need to be mended before a CPTPP accession.[112]

Enlargement summary[]

| Country | TPP | CPTPP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Status | Date | ||

| Non signatory | Working group of the accession is established[113] | 2 June 2021 | |

| Formal application is submitted[96] | 16 September 2021 | ||

| Formal application is submitted[114] | 22 September 2021 | ||

| Former signatory | Announced Interest[104][105] | January 2018 | |

| Non signatory | Announced Interest[115] | 2018 | |

| Announced Interest[115] | 2018 | ||

| Announced Interest[115] | 2018 | ||

| Announced Interest[115] | 2018 | ||

| Announced Interest[116] | 3 February 2021 | ||

Criticism[]

Economist has criticized the treaty for severely restricting the sovereignty of the signatories.[117] Signatories are subject to international courts and have restrictions on what their state-owned enterprises can do.[118] According to Palma the treaty makes it difficult for countries to implement policies aimed to diversify exports thus becoming a so-called middle income trap.[117] Palma also accuses that the treaty is reinforcing unequal relations by being drafted to reflect the laws of the United States.[118]

In the case of Chile, Palma holds the treaty is redundant regarding the possibilities of trade as Chile has already trade treaties with ten of its members.[118] On the contrary, economist consider that the CPTPP "deepening" of already existing trade relations of Chile is a point in favour it.[119] In the view of Schmidt-Hebbel approving the treaty is important for the post-Covid economic recovery of Chile and wholy in line with the economic policies of Chile since the 1990s.[119]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Pleno aprueba Tratado Integral y Progresista de Asociación Transpacífico". Congreso. 14 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership" (PDF). Government of New Zealand. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "大筋合意に至ったTPP11 包括的及び先進的な環太平洋パートナーシップ協定" (PDF) (in Japanese). Mizuho Research Institute. 13 November 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Benson, Simon (25 January 2018). "$13.7 trillion TPP pact to deliver boost in GDP". The Australian. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Blanco, Daniel (23 January 2018). "Se alcanza acuerdo en texto final del TPP11". El Financiero (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Australia ratifies the TPP-11, Media release, 31 Oct 2018, Australian Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment, Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham". trademinister.gov.au. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Torrey, Zachary (3 February 2018). "TPP 2.0: The Deal Without the US". The Diplomat. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Riley, Charles (23 January 2017). "Trump's decision to kill TPP leaves door open for China". CNN Money. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Jegarajah, Sri; Dale, Craig; Shaffer, Leslie (21 May 2017). "TPP nations agree to pursue trade deal without US". CNBC. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ Staff writers (21 May 2017). "Saving the Trans-Pacific Partnership: What are the TPP's prospects after the US withdrawal?". The Straits Times. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ In America's absence, Japan takes the lead on Asian free trade Washington Post

- ^ 기자, 최경환. "'한국은 중국 편' 오해사면 끝…일본 주도 TPP에 막차 타나". news.naver.com.

- ^ "Record China".

- ^ "日本主導のTPP大筋合意…韓国自動車産業にマイナスの影響". 中央日報 - 韓国の最新ニュースを日本語でサービスします.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dwyer, Colin (8 March 2018). "The TPP Is Dead. Long Live The Trans-Pacific Trade Deal". The Two-Way. NPR. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Goodman, Matthew P. (8 March 2018). "From TPP to CPTPP". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b AP Staff (8 March 2018). "11 nations to sign Pacific trade pact as US plans tariffs". New York Daily News. Associated Press. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Swick, Brenda C.; Augruso, Dylan E. (19 January 2018). "Canada Reaches Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement". The National Law Review. Dickinson Wright PLLC. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pacific trade pact to start at end-2018 after six members ratify". Reuters. 31 October 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "'We weren't ready' to close deal: Trudeau defends Canada's actions on TPP". CBC News. 11 November 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Canada reaches deal on revised Trans-Pacific Partnership". CBC News. 23 January 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Minister Carr calls on Manitoba businesses to expand their horizons with the help of the CPTPP". Government of Canada. 13 February 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mexico's senate ratifies sweeping Asia-Pacific trade deal". Reuters. 25 April 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "CPTPP law in the House as Mexico first to ratify". The Beehive. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "[Press Releases] Notification of Completion of Domestic Procedures for the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement ." Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ "Japan, world's third largest economy, ratifies CPTPP". The Beehive. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "CPTPP". Ministry of Trade and Industry (Singapore). Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Singapore becomes third nation to ratify CPTPP". The Beehive. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ "Australia becomes fourth signatory country to ratify CPTPP". vietnamplus.vn. 17 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Customs Amendment (Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership Implementation) Bill 2018 Australian Parliament

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Customs Tariff Amendment (Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership Implementation) Bill 2018 Australian Parliament

- ^ Jump up to: a b "New Zealand ratifies CPTPP during trade minister's trip to Ottawa and Washington". The Beehive. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "LEGISinfo - House Government Bill C-79 (42-1)". www.parl.ca. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Senate of Canada on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Canada, Global Affairs (29 October 2018). "Statement by Minister Carr on Canada's Ratification of Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership". gcnws. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McGregorl, Janyce (29 October 2018). "Canada ratifies, Pacific Rim trade deal set to take effect by end of year". CBC. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Government of Canada, Foreign Affairs Trade and Development Canada. "Timeline of discussions". GAC. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ "Trans-Pacific trade agreement submitted to NA for approval". THE VOICE OF VIETNAM. 2 November 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ "NA ratifies CPTPP trade deal". THE VOICE OF VIETNAM. 12 November 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Viet Nam seventh nation to ratify CPTPP". New Zealand Government. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ "Chile: Hundreds protest in Santiago as TPP-11 moves closer to ratification | Video Ruptly". www.ruptly.tv.

- ^ "Mexico's senate ratifies sweeping Asia-Pacific trade deal". Access to Energy. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "Japan's lower house passes TPP-11, pushing related trade bills". The Japan Agrinews. 30 May 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "Japanese Senate Ratifies CPTPP Protocol". Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Trans-Pacific Partnership: parliamentary steps to ratification". Parliament of New Zealand. 31 October 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

This paper sets out the framework for parliamentary involvement in the process leading up to the ratification of an international multilateral trade treaty

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (CPTPP) Amendment Bill". New Zealand Parliament. 24 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ "Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (CPTPP) Amendment Bill - Third Reading - Video 15". In The House Youtube Channel. 24 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ "House Government Bill (C-79)". LEGISinfo, Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ "Landmark TPP-11 passes through House of Representatives". Australian DFAT. 19 September 2018. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ "TPP passes the Senate, Australian exporters to win: PM Scott Morrison". Australian Financial Review. 17 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ "National Assembly passes resolution ratifying CPTPP". Nhân Dân. 12 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ Vu, Khanh (12 November 2018). "Vietnam becomes seventh country to ratify Trans-Pacific trade pact". Reuters. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) - Joint Ministerial Statement on the occasion of the Fifth Commission Meeting" (PDF). 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Peruvian Congress ratifies the Trans-Pacific Partnership Treaty". The Rio Times. 15 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ Azzopardi, Tom (17 April 2019). "Chile's Lower House Ratifies Trans-Pacific Trade Deal". Bloomberg Law. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ "CÁMARA APROBÓ ACUERDO TRANSPACÍFICO-11". Cámara de Diputados de la República de Chile (in Spanish). 17 April 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Elms, Deborah Kay (23 January 2019). "The Unsexy Challenge of CPTPP". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ "News First CPTPP Commission Meeting". 21 January 2019. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "TPP Commission". Prime Minister's Official Residence (Japan). 19 January 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Decision by the Commission of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans‐Pacific Partnership regarding Administration for Implementation of the CPTPP" (PDF). 19 January 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Decision by the Commission of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans‐Pacific Partnership regarding Accession Process of the CPTPP" (PDF). 19 January 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans‐Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) Accession Process" (PDF). 19 January 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Decision by the Commission of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans‐Pacific Partnership regarding SSDS Rules of Procedures for Panels" (PDF). 19 January 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "RULES OF PROCEDURE UNDER CHAPTER 28 (DISPUTE SETTLEMENT) OF THE COMPREHENSIVE AND PROGRESSIVE AGREEMENT FOR TRANS-PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP" (PDF). 19 January 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "ANNEX I CODE OF CONDUCT FOR STATE-STATE DISPUTE SETTLEMENT UNDER CHAPTER 28 (DISPUTE SETTLEMENT) OF THE COMPREHENSIVE AND PROGRESSIVE AGREEMENT FOR TRANS-PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP" (PDF). 19 January 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Decision by the Commission of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans‐Pacific Partnership regarding ISDS Code of Conduct" (PDF). 19 January 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "CODE OF CONDUCT FOR INVESTOR-STATE DISPUTE SETTLEMENT UNDER CHAPTER 9 SECTION B (INVESTOR-STATE DISPUTE SETTLEMENT) OF THE COMPREHENSIVE AND PROGRESSIVE AGREEMENT FOR TRANS-PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP" (PDF). 19 January 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership Ministerial Statement Tokyo, Japan, January 19, 2019" (PDF). 19 January 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "COMMISSION REPORT CPTPP/COM/2019/REPORT" (PDF). 19 October 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) 2nd CPTPP Commission, Auckland, 9 October 2019 Concluding Joint Statement" (PDF). 19 October 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ "Third CPTPP Commission Meeting". 6 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "Decision by the Commission of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership regarding the United Kingdom's Formal Request to Commence the Accession Process" (PDF). 2 June 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Decision by the Commission of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership regarding the Establishment of a Committee on Electronic Commerce" (PDF). 1 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "As UK joins CPTPP hopefuls, S. Korea hurries to prepare application". english.hani.co.kr. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ "Formal Request to Commence UK Accession Negotiations to CPTPP". GOV.UK. 1 February 2021.

- ^ "UK applying to join Asia-Pacific free trade pact CPTPP". BBC News. 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ "Brexit: Japan 'would welcome' UK to TPP says Abe". BBC News. 8 October 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Britain to apply to join CPTPP Asia-Pacific free trade bloc". Japan Times. 31 January 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Gregory, Julia (3 January 2018). "Britain exploring membership of the TPP to boost trade after Brexit". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ Lowe, Sam (5 January 2018). "TPP: The UK is having a Pacific pipe dream". Prospect. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

For one, unless we are planning on assigning far greater significance to the Pitcairn Islands (which form the last British overseas territory in the region) the UK is not a Pacific power, so the name of the trade deal would need to change.

- ^ McCurry, Justin (8 October 2018). "UK welcome to join Pacific trade pact after Brexit, says Japanese PM". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ Truss, Liz (28 April 2020). "Enemies of free trade must not be allowed to use coronavirus to bring back protectionism". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Watkins, Tracy (3 April 2012). "Diplomats take the gloves off". Stuff. Archived from the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "[Withdrawn] UK approach to joining the CPTPP trade agreement". GOV.UK.

- ^ "Foreign direct investment involving UK companies (directional): outward - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk.

- ^ "UK total trade: all countries, non-seasonally adjusted - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk.

- ^ ""HM Revenue & Customs: UK Imports and Exports by Region, year to March 2020"". Archived from the original on 29 January 2017.

- ^ @trussliz (15 December 2020). "