Conservative vector field

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2009) |

In vector calculus, a conservative vector field is a vector field that is the gradient of some function.[1] Conservative vector fields have the property that the line integral is path independent; the choice of any path between two points does not change the value of the line integral. Path independence of the line integral is equivalent to the vector field being conservative. A conservative vector field is also irrotational; in three dimensions, this means that it has vanishing curl. An irrotational vector field is necessarily conservative provided that the domain is simply connected.

Conservative vector fields appear naturally in mechanics: They are vector fields representing forces of physical systems in which energy is conserved.[2] For a conservative system, the work done in moving along a path in configuration space depends on only the endpoints of the path, so it is possible to define a potential energy that is independent of the actual path taken.

Informal treatment[]

In a two- and three-dimensional space, there is an ambiguity in taking an integral between two points as there are infinitely many paths between the two points—apart from the straight line formed between the two points, one could choose a curved path of greater length as shown in the figure. Therefore, in general, the value of the integral depends on the path taken. However, in the special case of a conservative vector field, the value of the integral is independent of the path taken, which can be thought of as a large-scale cancellation of all elements that don't have a component along the straight line between the two points. To visualize this, imagine two people climbing a cliff; one decides to scale the cliff by going vertically up it, and the second decides to walk along a winding path that is longer in length than the height of the cliff, but at only a small angle to the horizontal. Although the two hikers have taken different routes to get up to the top of the cliff, at the top, they will have both gained the same amount of gravitational potential energy. This is because a gravitational field is conservative. As an example of a non-conservative field, imagine pushing a box from one end of a room to another. Pushing the box in a straight line across the room requires noticeably less work against friction than along a curved path covering a greater distance.

Intuitive explanation[]

M. C. Escher's lithograph print Ascending and Descending illustrates a non-conservative vector field, impossibly made to appear to be the gradient of the varying height above ground as one moves along the staircase. It is rotational in that one can keep getting higher or keep getting lower while going around in circles. It is non-conservative in that one can return to one's starting point while ascending more than one descends or vice versa. On a real staircase, the height above the ground is a scalar potential field: If one returns to the same place, one goes upward exactly as much as one goes downward. Its gradient would be a conservative vector field and is irrotational. The situation depicted in the painting is impossible.

Definition[]

A vector field , where is an open subset of , is said to be conservative if and only if there exists a (continuously differentiable) scalar field on such that

Here, denotes the gradient of . When the equation above holds, is called a scalar potential for .

The fundamental theorem of vector calculus states that any vector field can be expressed as the sum of a conservative vector field and a solenoidal field.

Path independence and conservative vector field[]

Path independence[]

A line integral of a vector field is said to be path-independent if it depends on only two integral path endpoints regardless of which path between them is chosen:[3]

for any pair of integral paths and between a given pair of path endpoints in . The path independence is also equivalently expressed as

for a closed path in where the two endpoints are coincident. Two expressions are equivalent since any closed path can be made by two path; from an endpoint to another endpoint , and from to , so

where is the path that is the reverse of and the last equality holds due to the path independence

Conservative vector field[]

A key property of a conservative vector field is that its integral along a path depends on only the endpoints of that path, not the particular route taken. In other words, if it is a conservative vector field, then its line integral is path-independent. Suppose that is a rectifiable path in with an initial point and a terminal point . If for some (continuously differentiable) scalar field so that is a conservative vector field, then the gradient theorem (also called fundamental theorem of calculus for line integrals) states that

This holds as a consequence of the definition of a line integral, the chain rule, and the second fundamental theorem of calculus. in the line integral is an exact differential for an orthogonal coordinate system (e.g., Cartesian, cylindrical, or spherical coordinates).[4]

This path independence is also equivalently expressed as

for every rectifiable simple closed path in . For a 3-dimensional space, this path independence expression can also be proved by using the vector calculus identity and the Stokes' theorem for a rectifiable simple closed path with the smooth oriented surface in it. Again, for a 3-dimensional space, the converse of this statement is also true: If the circulation (the line integral along a closed path) of a vector field around every rectifiable simple closed path in is , then is a conservative vector field.

So far it has been proven that a conservative vector field is line integral path-independent. Conversely, if a vector field is (line integral) path-independent, then it is a conservative vector field, so the following biconditional statement holds:[3]

- For a vector field , where is an open subset of , it is conservative if and only if its line integral along a path in is path-independent, meaning that the line integral depends on only both path endpoints regardless of which path between them is chosen.

The proof of this converse statement is the following.

is a vector field which line integral is path-independent. Then, let's make a function defined as

over an arbitrary path between a chosen starting point and an arbitrary point . Since it is path-independent, it depends on only and regardless of which path between these points is chosen.

Let's choose the path shown in the left of the right figure where a 2-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system is used. The second segment of this path is parallel to the axis so there is no change along the axis. The line integral along this path is

- .

By the path independence, its partial derivative with respect to is

since and are independent to each other. Let's express as where and are unit vectors along the and axes respectively, then, since ,

where the last equality is from the second fundamental theorem of calculus.

A similar approach for the line integral path shown in the right of the right figure results in so

is proved for the 2-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system. This proof method can be straightforwardly expanded to a higher dimensional orthogonal coordinate system (e.g., a 3-dimensional spherical coordinate system) so the converse statement is proved.

Irrotational vector fields[]

Let (3-dimensiontal space), and let be a (continuously differentiable) vector field, with an open subset of . Then is called irrotational if and only if its curl is everywhere in , i.e., if

For this reason, such vector fields are sometimes referred to as curl-free vector fields or curl-less vector fields. They are also referred to as longitudinal vector fields.

It is an identity of vector calculus that for any (continuously differentiable up to the 2nd derivative) scalar field on , we have

Therefore, every conservative vector field on is also an irrotational vector field on .

Provided that is simply connected, the converse of this is also true: Every irrotational vector field on is a conservative vector field on .

The above statement is not true in general if is not simply connected. Let be with the -axis removed, i.e., . Now, define a vector field on by

Then has zero curl everywhere in , i.e., is irrotational. However, the circulation of around the unit circle in the -plane is . Indeed, note that in polar coordinates, , so the integral over the unit circle is

Therefore, does not have the path-independence property discussed above and is not conservative.

In a simply connected open region, an irrotational vector field has the path-independence property. This can be seen by noting that in such a region, an irrotational vector field is conservative, and conservative vector fields have the path-independence property. The result can also be proved directly by using Stokes' theorem. In a simply connected open region, any vector field that has the path-independence property must also be irrotational.

More abstractly, in the presence of a Riemannian metric, vector fields correspond to differential -forms. The conservative vector fields correspond to the exact -forms, that is, to the forms which are the exterior derivative of a function (scalar field) on . The irrotational vector fields correspond to the closed -forms, that is, to the -forms such that . As , any exact form is closed, so any conservative vector field is irrotational. Conversely, all closed -forms are exact if is simply connected.

Vorticity[]

The vorticity of a vector field can be defined by:

The vorticity of an irrotational field is zero everywhere.[5] Kelvin's circulation theorem states that a fluid that is irrotational in an inviscid flow will remain irrotational. This result can be derived from the vorticity transport equation, obtained by taking the curl of the Navier-Stokes Equations.

For a two-dimensional field, the vorticity acts as a measure of the local rotation of fluid elements. Note that the vorticity does not imply anything about the global behavior of a fluid. It is possible for a fluid traveling in a straight line to have vorticity, and it is possible for a fluid that moves in a circle to be irrotational.

Conservative forces[]

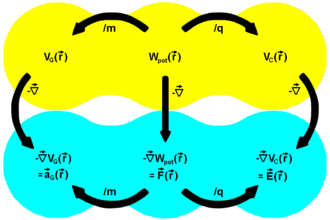

- Scalar fields, scalar potentials:

- VG, gravitational potential

- Wpot, potential energy

- VC, Coulomb potential

- Vector fields, gradient fields:

- aG, gravitational acceleration

- F, force

- E, electric field strength

If the vector field associated to a force is conservative, then the force is said to be a conservative force.

The most prominent examples of conservative forces are the gravitational force and the electric force associated to an electrostatic field. According to Newton's law of gravitation, the gravitational force acting on a mass due to a mass , which is a distance between them, obeys the equation

where is the gravitational constant and is a unit vector pointing from toward . The force of gravity is conservative because , where

is the gravitational potential energy. It can be shown that any vector field of the form is conservative, provided that is integrable.

For conservative forces, path independence can be interpreted to mean that the work done in going from a point to a point is independent of the path chosen, and that the work done in going around a simple closed loop is :

The total energy of a particle moving under the influence of conservative forces is conserved, in the sense that a loss of potential energy is converted to an equal quantity of kinetic energy, or vice versa.

See also[]

- Beltrami vector field

- Conservative force

- Conservative system

- Complex lamellar vector field

- Helmholtz decomposition

- Laplacian vector field

- Longitudinal and transverse vector fields

- Solenoidal vector field

References[]

- ^ Marsden, Jerrold; Tromba, Anthony (2003). Vector calculus (Fifth ed.). W.H.Freedman and Company. pp. 550–561.

- ^ George B. Arfken and Hans J. Weber, Mathematical Methods for Physicists, 6th edition, Elsevier Academic Press (2005)

- ^ a b Stewart, James (2015). "16.3 The Fundamental Theorem of Line Integrals"". Calculus (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 1127–1134. ISBN 978-1-285-74062-1.

- ^ Need to verify if exact differentials also exist for non-orthogonal coordinate systems.

- ^ Liepmann, H.W.; Roshko, A. (1993) [1957], Elements of Gas Dynamics, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-41963-0, pp. 194–196.

Further reading[]

- Acheson, D. J. (1990). Elementary Fluid Dynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198596790.

- Vector calculus

- Force