Cosmology of Tolkien's legendarium

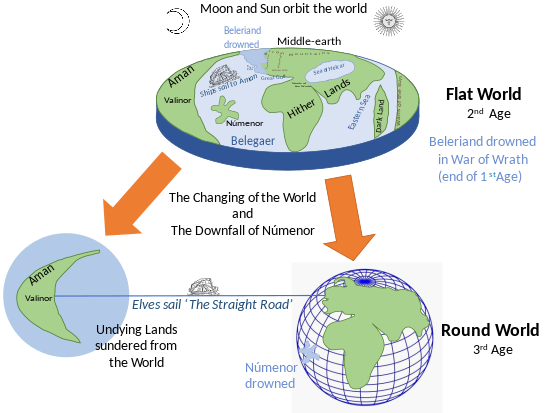

The cosmology of J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium combines aspects of Christian theology and metaphysics, mythology (especially Germanic mythology) and pre-modern cosmological concepts in the flat Earth paradigm with the modern spherical Earth view of the solar system.[T 1]

Tolkien's cosmology is based on a clear dualism between the spiritual and the material world. While the Ainur, the first-created but immaterial angelic beings, have the "subcreative" power of imagination, the power to create independent life or physical reality is reserved for Eru Ilúvatar (God); this power of (primary) creation is expressed by the concept of a "Secret Fire" or "Flame Imperishable". The term for the material universe is Eä, "the World that Is",[T 2] as distinguished from the purely idealist pre-figuration of creation in the minds of the Ainur. Eä contains our Earth (and solar system) in a mythical ancient past, of which Middle-earth is the main continent. Eä (Quenya for "let [these things] be!") was the word "spoken" by Eru Ilúvatar to bring the physical universe into actuality.

Ontology and creation[]

Eru Ilúvatar[]

Eru is introduced in The Silmarillion as the supreme being of the universe, creator of all existence. In Tolkien's invented Elvish language Quenya, Eru means "The One", or "He that is Alone"[T 3] and Ilúvatar signifies "Allfather".[T 4] The names appear in Tolkien's work both in isolation and paired (Eru Ilúvatar).

In earlier versions of the legendarium, the name Ilúvatar meant "Father for Always" (in The Book of Lost Tales, published as the first two volumes of The History of Middle-earth), then "Sky-father",[T 5] but these etymologies were dropped in favour of the newer meaning in later revisions. Ilúvatar was also the only name of God used in earlier versions – the name Eru first appeared in "The Annals of Aman", published in Morgoth's Ring, the tenth volume of The History of Middle-earth.

Creation account[]

Eru first created a group of angelic beings, called in Elvish the Ainur, and these were co-actors in the creation of the universe through a holy music and chanting called the "Music of the Ainur", or Ainulindalë in Elvish.[T 6] Eru alone could create independent life or reality by giving it the Flame Imperishable. All beings not created directly by Eru (e.g., Dwarves, Ents, Eagles) still needed to be accepted by Eru to become more than mere puppets of their creator. The evil Melkor, who had originally been Eru's most powerful servant, desired the Flame Imperishable and long sought for it in vain, but he could only twist that which had already been given life.[T 7]

"I am a servant of the Secret Fire, wielder of the flame of Anor. You cannot pass. The dark fire will not avail you, flame of Udûn. Go back to the shadow! You cannot pass."

– Gandalf the Grey, speaking to the Balrog on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm in the Mines of Moria, The Fellowship of the Ring

The "Flame Imperishable" or "Secret Fire" represents the Holy Spirit in Christian theology,[1] the creative activity of Eru, inseparable both from him and from his creation. In the interpretation of Christopher Tolkien, it represents "the mystery of authorship", the author both standing outside of his work and indwelling in it.[2]

The abode of Eru and the Ainur outside of time or the physical universe is also called the "Timeless Halls" (Heaven). Tolkien made a point of keeping the ultimate fate of the souls of Men and the nature of their mortality open, and unknown to the Elves (who are tied to the physical world for the time of its duration, and Christian eschatology is not applicable to them). In the tale of Adanel it is suggested that Men return to Eru after death.

The account of the "events" predating creation is not presented from an omniscient perspective but presented as a fictional tradition, purportedly a record of the account given by the Valar to the Elves in Aman, and from there transmitted to Middle-earth, and translated from Valarin at first into Quenya and later into human languages. It is understood that the Valar, who were present at the moment of creation as Ainur, gave an honest account to the Elves, but were constrained by the limitations of language, the description of the "Music" or of the words "spoken" by Eru, or his "Halls" and the secret "Flame" etc. are to be taken as metaphors.

In the First Age, Eru alone created Elves and Men. This is why in The Silmarillion both races are called the Children of Ilúvatar. The story of their creation is told in the Quenta Silmarillion. Elves are also named the Minnónar in Quenya[T 8] ("Firstborn") and Men are the Apanónar ("Those born after" or "Afterborn") because the Elves were the first of the Children of Ilúvatar to awake in Middle-earth, whereas Men were not intended to follow until the beginning of the First Age many years later.

The race of the Dwarves was created by Aulë, and given sapience by Eru. Animals and plants were fashioned by Yavanna during the Music of the Ainur after the themes set out by Eru. The Eagles of Manwë were created from the thought of Manwë and Yavanna. Yavanna also created the Ents, who were given sapience by Eru. Melkor instilled some semblance of free will into his mockeries of Eru Ilúvatar's creations (Orcs, mocking Elves and perhaps Men; Trolls, mocking Ents; and perhaps Dragons, mocking Eagles).

Eru's direct interventions[]

In the Second Age, Eru buried King Ar-Pharazôn of Númenor and his army when they landed at Aman in the Second Age, trying to reach the Undying Lands, which they wrongly supposed would give them immortality. He caused the Earth to take a spherical shape, drowned Númenor, and caused the Undying Lands to be taken "outside the spheres of the earth".[3]

When Gandalf died in the fight with the Balrog in The Fellowship of the Ring, it was beyond the power of the Valar to resurrect him; Eru himself intervened to send Gandalf back.[T 9]

Discussing Frodo's failure to destroy the Ring in The Return of the King, Tolkien indicates in a letter that "the One" does intervene actively in the world, pointing to Gandalf's remark to Frodo that "Bilbo was meant to find the Ring, and not by its maker", and to the eventual destruction of the Ring despite Frodo's failure to complete the task.[T 10]

Tolkien on Eru and subcreation[]

Peter Hastings, manager of the Newman Bookshop (a Catholic bookshop in Oxford), had written to Tolkien objecting to his writing of the reincarnation of Elves, saying:[T 11]

God has not used that device in any of the creations of which we have knowledge, and it seems to me to be stepping beyond the position of a sub-creator to produce it as an actual working thing, because a sub-creator, when dealing with the relations between creator and created, should use those channels which he knows the creator to have used already.[T 11]

In a 1954 draft of a reply to Hastings, Tolkien, also a devout Roman Catholic, defended his creative ideas as an exploration of the infinite "potential variety" of God: that it need not conform to the reality of our world so long as it does not misrepresent the essential nature of the divine:[T 11]

We differ entirely about the nature of the relation of sub-creation to Creation. I should have said that liberation "from the channels the creator is known to have used already" is the fundamental function of "sub-creation", a tribute to the infinity of His potential variety ... I am not a metaphysician; but I should have thought it a curious metaphysic – there is not one but many, indeed potentially innumerable ones – that declared the channels known (in such a finite corner as we have any inkling of) to have been used, are the only possible ones, or efficacious, or possibly acceptable to and by Him![T 11]

Hastings had also criticised the description of Tom Bombadil by Goldberry simply as "He is", saying that this seemed to be a reference to the Biblical quotation "I Am that I Am", implying that Bombadil was God. Tolkien denied this:[T 11]

I really do think you are being too serious, besides missing the point. ... You rather remind me of a Protestant relation who to me objected to the (modern) Catholic habit of calling priests Father, because the name father belonged only to the First Person.[T 11]

Fëa and hröa[]

Fëa and hröa are words for "soul" (or "spirit") and "body" of the Children of Ilúvatar, Elves and Men. Their hröa is made out of the matter of Arda (erma); for this reason hröar are Marred (or, using another expression by Tolkien himself, contain a "Melkor ingredient"[T 12]). When an Elf dies, the fëa leaves the hröa, which then "dies". The fëa is summoned to the Halls of Mandos, where it is judged; however as with death their free-will is not taken away, they could refuse the summons.[T 13] If allowed by Mandos, the fëa may be re-embodied into a new body that is identical to the previous hröa. (In earlier versions of the legendarium it may also re-enter the incarnate world through child-birth.)[T 14] The situation of Men is different: a Mannish fëa is only a visitor to Arda, and when the hröa dies, the fëa, after a brief stay in Mandos, leaves Arda completely. Originally men could "surrender themselves: die of free will, and even of desire, in estel"[T 15] but Melkor made Men fear death, instead of accept with joy the Gift of Eru.

Unseen world[]

In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien justifies the nature of the Ring by explaining that Elves and other immortal beings dwell in "both worlds" at once (the physical and the spiritual, or Unseen world) and have great power in both, especially those who have dwelt in the light of the Two Trees before the Sun and Moon; and that the powers associated with "magic" were spiritual in nature.[T 16][T 17] Mortals on the other hand are chained to their bodies, have less influence upon them, and their fëa depart the world without them. This posed a problem for immortal beings whose spirits do not wane over time, but become increasingly dependent on their physical bodies.

The Elves who stayed in Middle-earth where Melkor once was dominant, being in bodies and surrounded by things that are themselves marred and subject to decay by the influence of Melkor, created the Elven Rings out of a desire to preserve the physical world unchanged; as it were in the Undying Lands of Valinor, home of the Valar. Without the rings they are destined to eventually "fade", eventually becoming shadows in the physical world, prefiguring the concept of Elves as dwelling in a separate and often-underground (or overseas) plane in historical European mythology.[T 18] Mortals who wear a Ring of Power are destined to "fade" much more rapidly, as the rings unnaturally preserve their life-span turning them into wraiths. Invisibility is a side-effect of this, as the wearer is temporarily pulled into the spirit-world.[T 19][T 20] Immortal beings, however, became trapped in their bodies over long periods of time, subject to reincarnation only if their bodies were destroyed.

Evil in Middle-earth[]

Tolkien used the first part of The Silmarillion, the creation account, to describe his thoughts on the origin of evil in his fictional world, which he took pains to comport with his own beliefs on the subject, as accounted in Tolkien's Letters. These beliefs were elaborated on both early and late in life, and Tolkien sought to bring them consistently in line with his views on evil in the real world; in contrast to widespread critical reception of Tolkien's works as somehow depicting, or even fondly imagining, a binary clash between absolute good and evil.

In Tolkien's legendarium, evil represents a rebellion against the creative process set in motion by Eru. Evil is defined by its original actor, Melkor, a Luciferian figure who falls from grace in active rebellion against Eru, out of a desire to create and control things of his own that do not comport with the harmonies of the other angelic beings. As it originates with Melkor, whose ideas and conceptions are subservient to the will of Eru, his evil by definition constitutes a relative absence of good, in the Augustinian tradition, rather than an opposing force to the will of God in the Manichaean tradition. Eru explicitly denies Melkor's desire to be a demiurge, and his actions in defiance of the creative will of Eru are marked as evil in that sense; Tolkien rejected Gnosticism of the sort depicted in the mythopoeia of William Blake.

The "good" angels led by Melkor's brother Manwë are inspired directly by Eru's teachings, and seek to carry out his wishes directly, but lacking themselves the ability to create things not inspired by Eru, they do not necessarily understand the nature of evil; Manwë subsequently releases Melkor from imprisonment, seeking his redemption, as he is incapable of fully understanding Melkor's hatred. However, Eru takes one of the Ainur aside (Ulmo, the Vala of water) and shows him a vision of snow, ice and rain; things which Ulmo had not envisioned, which were made possible by the extremes of heat and cold imagined by Melkor. Thus, in describing the new Creation, Eru tells Melkor and the others that:

... no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined. [...] and each of you shall find contained [in the design of creation] all those things which it may seem that [you yourself] devised or added. And thou, Melkor, wilt discover all the secret thoughts of thy mind, [and] perceive that they are but a part of the whole and tributary to its glory.[T 21]

Through Manwë, Tolkien suggests that the plot of the main story itself, the 500-year war of the Silmarils, is an example of this principle in action:

... when the messengers declared to Manwë the [words] of Fëanor... Manwë wept and bowed his head. But at that last word of Fëanor: that at the [very] least the Noldor [would] do deeds to live in song for ever, he raised his head, as one that hears a voice far off, and he said: ‘So shall it be! Dear-bought those songs shall be accounted, and yet shall be well-bought. For the price could be no other. Thus even as Eru spoke to us shall beauty not before conceived be brought into Eä, and evil yet be good to have been.’[T 22]

This leads Melkor to envy the resulting creation and seek to destroy it, becoming the ultimate nihilist. Tolkien explains that Melkor would not be satisfied with control, for the very matter of creation would remain the vision of Eru, and thus, evil could not have the mastery in the end, even if the world were destroyed.[T 23] Evil in Tolkien's world is thus, in and of itself, incapable of creative impulse:

Evil is fissiparous. But itself barren. Melkor could not 'beget'.... Out of the discords of the Music—sc. not directly out of either of the themes, Eru's or Melkor's, but of their dissonance with regard one to another—evil things appeared in Arda, which did not descend from any direct plan or vision of Melkor: they were not 'his children'; and therefore, since all evil hates, hated him too.[T 24]

However, Tolkien also emphasized that all beings with free will would be subject to a similar fall, due to being given the choice to reject the will of Eru or embrace the harmony of creation. In Morgoth's Ring and in his notes written late in life, Tolkien spent much time on issues of cosmology and theology within the fictional universe, and described how Melkor, as the original evil, represented the only "pure" evil in the story; all other beings were redeemable provided free will, and even Melkor himself was not evil in origin, being the creation of the fundamentally good supreme being. In an effort to subvert creation, Tolkien describes in these notes how Melkor poured his spiritual essence into the very fabric of matter, such that all of Middle-earth was the equivalent of Sauron's Ring for Melkor, hence the title of the volume.[T 25]

The End of Days[]

Tolkien's world ends in Dagor Dagorath.[T 26]

The physical universe[]

Eä[]

Eä is the Quenya name for the material universe as a realization of the vision of the Ainur. The word comes from the Quenya word for to be. Thus, Eä is the World that Is, as distinguished from the World that Is Not. "Eä" was the word spoken by Eru Ilúvatar by which he brought the universe into actuality.[T 6]

The Void[]

The Void (also known as Avakúma, Kúma, the Outer Dark, the Eldest Dark, and the Everlasting Dark) is the nothingness outside Arda. From Arda, it is accessible through the Doors of Night. The Valar exiled Melkor to the Void after his defeat in the War of Wrath. Legend foretells that Melkor will return to Arda just before the apocalyptic battle of Dagor Dagorath. Avakúma is not to be confused with the state of non-being that preceded the creation of Eä.[T 27]

Stars[]

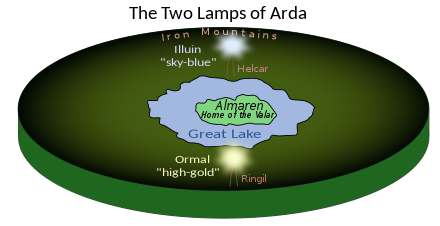

When Arda (the Earth) was created, "innumerable stars" were already in existence.[T 6] To provide greater light, the Valar later created the Two Lamps in Middle-earth, and when these were destroyed they created the Two Trees of Valinor. These gave rise to the Ages of the Lamps and the Years of the Trees, however the Ages of the Stars did not conclude until the creation of the Sun.[T 28]

During the Years of the Trees, shortly before the Awakening of the Elves, Varda created the Great Stars: "new stars and brighter" and constellations.[T 29] The Elves venerated stars; one of the names of the Elvish race is Eldar: "People of the Stars".[T 30]

Flat-earth cosmology[]

Arda[]

Ilúvatar created Arda (Earth) according to a flat Earth cosmology. This disc-like Arda has continents and the seas, and the moon and the stars revolve around it. Arda was created to be the "Habitation" (Imbar or Ambar) for the Children of Ilúvatar (Elves and Men).[4]

This world was, at first, not lit by a sun. Instead, the Valar created two lamps to illuminate it: Illuin ('Sky-blue') and Ormal ('High-gold'). To support the lamps, the Vala Aulë forged two enormous pillars of rock: Helcar in the north of the continent Middle-earth, and Ringil in the south. Illuin was set upon Helcar and Ormal upon Ringil. Between the columns, where the light of the lamps mingled, the Valar dwelt on the island of Almaren in the midst of a Great Lake.[T 31]

When Melkor destroyed the Lamps, two vast inland seas (Helcar and Ringil) and two major seas (Belegaer and the Eastern Sea) were created, but Almaren and its lake were destroyed.[T 29]

The Valar left Middle-earth, and went to the newly formed continent of Aman in the west, where they created their home called Valinor. To discourage Melkor from assailing Aman, they thrust the continent of Middle-earth to the east, thus widening Belegaer at its middle, and raising five major mountain ranges in Middle-earth: the Blue, Red, Grey, and Yellow Mountains, plus the Mountains of the Wind. This act disrupted the symmetrical shapes of the continents and seas.

Ekkaia[]

Ekkaia, also called the Enfolding Ocean and the Encircling Sea, is a dark sea that surrounds the world before the cataclysm at the end of the Second Age. During this flat-Earth period, Ekkaia flows completely around Arda, which floats on it like a ship on a sea. Above Ekkaia is a layer of atmosphere. Ulmo the Lord of Waters dwells in Ekkaia, underneath Arda. Ekkaia is extremely cold; where its waters meet the waters of the ocean Belegaer on the northwest of Middle-earth, a chasm of ice is formed: the Helcaraxë. Ekkaia cannot support any ships except the boats of Ulmo. The ships of the Númenóreans that tried to sail on it sank, drowning the sailors. The Sun passes through Ekkaia on its way around the world, warming it as it passes.[T 31][T 32]

Ilmen[]

Ilmen is a region of clean air pervaded by light, before the cataclysm at the end of the Second Age. The stars and other celestial bodies are in this region. The Moon passes through Ilmen on its way around the world, plunging down the Chasm of Ilmen on its return.[T 32]

Spherical-earth cosmology[]

Tolkien's legendarium addresses the spherical Earth paradigm by depicting a catastrophic transition from a flat to a spherical world, in which Aman, the continent where Valinor lay, was removed "from the circles of the world".[3] The only remaining way to reach Aman was the so called Straight Road, a hidden route leaving Middle-earth's curvature through sky and space which was exclusively known and open to the Elves, who were able to navigate it with their ships.

This transition from a flat to a spherical Earth is at the center of Tolkien's "Atlantis" legend. His unfinished The Lost Road suggests a sketch of the idea of historical continuity connecting the Elvish mythology of the First Age with the classical Atlantis myth, the Germanic migrations, Anglo-Saxon England and the modern period, presenting the Atlantis legend in Plato and other deluge myths as a "confused" account of the story of Númenor. The cataclysmic re-shaping of the world would have left its imprint on the cultural memory and collective unconscious of humanity, and even on the genetic memory of individuals. The "Atlantis" part of the legendarium explores the theme of the memory of a 'straight road' into the West, which now only exists in memory or myth, because the physical world has been changed.[T 1][3]

The Akallabêth says that the Númenóreans who survived the catastrophe sailed as far west as they could in search of their ancient home, but their travels only brought them around the world back to their starting points. Hence, before the end of the Second Age, the transition from "flat Earth" to "round Earth" had been completed. New lands were also created in the west, analogous to the New World. The same idea is expressed in The Lost Road, via an alliterating line in Primitive Germanic revealed to one protagonist: Westra lage wegas rehtas, nu isti sa wraithas – "Westward lay a straight way, but now it is bent."[T 33] The same sentence is recorded in Adûnaic, the original language of "Atlantis" revealed to one of the protagonists in The Notion Club Papers (written 1945), reading adûn izindi batân tâidô ayadda: îdô kâtha batîna lôkhî; this is glossed by the character who experienced the vision, within the fictional narrative, as: "west [a] straight road once went now all roads [are] crooked".[T 34]

A few years after publishing The Lord of the Rings, in a note associated with the unique narrative story "Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth" (which is said to occur in Beleriand during the War of the Jewels), Tolkien equated Arda with the Solar System; because Arda by this point consisted of more than one heavenly body (Valinor being on another planet and the Sun and Moon being celestial objects in their own right and not objects orbiting the Earth).[7]

Planets and constellations[]

Tolkien developed a list of names and meanings called the Qenya Lexicon. Christopher Tolkien included extracts from this in an appendix to The Book of Lost Tales, including mentions of specific stars, planets, and constellations in the entries: Gong, Ingil, Mornië, Morwinyon, Nielluin, Silindrin, and Telimektar.[8][9] The Sun was called Anor or Ur.[T 35][T 36] The Moon was called Ithil or Silmo.[T 37][T 38]

Ethereal regions[]

Fanyamar, Cloudhome, was the upper air where clouds form. Aiwenórë, Bird-land, was the lower air where the paths of birds are found. Vista, Air, was the atmosphere, the breathable air.

Planets[]

Tolkien gave names which cannot all be assigned definitely to specific planets. Silindo may be Jupiter; Carnil, Mars; Elemmire, Mercury; Luinil, Uranus; Lumbar, Saturn; and Nenar, Neptune.[T 39]

Eärendil's Star, Gil-Amdir,[T 40] Gil-Estel,[T 41] Gil-Oresetel, and Gil-Orrain[T 42] the light of a Silmaril, set on Eärendil's ship Vingilot, represents Venus. The English use of the word "earendel" in the Old English poem Christ A was found by 19th century philologists to be some sort of bright star, and from 1914 Tolkien took this to mean the morning-star. The line éala éarendel engla beorhtast "Hail, Earendel, brightest of angels" was Tolkien's inspiration. The Old English phrase is rendered in Quenya as Aiya Eärendil, elenion ancalima!

Individual stars[]

- Borgil (Aldebaran?)[10]

- Helluin, Gil,[T 43] Nielluin, Nierninwa (Sirius)[T 44]

- Morwinyon (Arcturus)[T 45]

Constellations[]

- Eksiqilta, Ekta (Orion's Belt)[T 46]

- Menelvagor, Daimord,[T 47] Menelmacar, Mordo,[T 48] Swordsman of the Sky, Taimavar, Taimondo, Telimbektar, Telimektar, Telumehtar (Orion)[T 49]—A constellation meant to represent Túrin Turambar and his eventual return to defeat Melkor in The Last Battle. Menelmacar superseded the older form, Telumehtar (which nonetheless continued in use), and was itself adopted into Sindarin as Menelvagor.

- Remmirath, Itselokte,[T 50] Sithaloth,[T 51] (Pleiades)[T 52]

- Valacirca, the Sickle of the Valar,[T 53] Burning Briar,[T 54] Durin's Crown,[T 55] Edegil,[T 56] Otselen, the Plough, Seven Stars,[T 57] Seven Butterflies,[T 58] Silver Sickle, Timbridhil,[T 59] (Ursa Major / Big Dipper)[T 60]—An important constellation of seven stars set in the sky by Varda as an enduring warning to Melkor and his servants, and which precipitated the Awakening of the Elves. It also formed the symbol of Durin, seen on the doors of Moria, and inspired a song of defiance from Beren. According to The Silmarillion it was set in the Northern Sky as a sign of doom for Melkor and a sign of hope for the Elves. The Valacirca is one of the few constellations named in the book, another significant one being Menelmacar.

- Wilwarin (generally held to be Cassiopeia)[T 61][11]

See also[]

References[]

Primary[]

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Actually in the imagination of this story we are now living on a physically round Earth. But the whole 'legendarium' contains a transition from a flat world ... to a globe ....", Letters, #154 to Naomi Mitchison, 25 September 1954

- ^ The Silmarillion, p. 9

- ^ The Silmarillion, p. 329; the root er means "one" or "alone" (p. 358)

- ^ The Silmarillion, p. 336; from ilúvë ("all, the whole", p. 360) and atar ("father", p. 356).

- ^ The Book of Lost Tales 1, Appendix, "Names in the Lost Tales Part1", entry for "Ilúvatar".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c The Silmarillion, "Ainulindalë"

- ^ Morgoth's Ring

- ^ The War of the Jewels, p. 403.

- ^ In Letters, #156, Tolkien clearly implies that the 'Authority' that sent Gandalf back was above the Valar (who are bound by Arda's space and time, while Gandalf went beyond time).

- ^ Letters, #192

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Letters, #153 to Peter Hastings, September 1954

- ^ Morgoth's Ring, p. 400

- ^ Morgoth's Ring, p. 339

- ^ Morgoth's Ring, pp. 361–366; Tolkien abandoned this conception in the 1950s.

- ^ Morgoth's Ring, 341. Estel is a kind of hope, the "trust in Eru."

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 1 "Many Meetings". "you saw him for a moment as he [is] upon the other side: [...] for those who have dwelt in the Blessed Realm live at once in both worlds, and against both the Seen and the Unseen they have great power."

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 7 "The Mirror of Galadriel"

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 7 "The Mirror of Galadriel". "yet if you succeed, then our power is diminished, and Lothlórien will fade, and the tides of Time will sweep it away. We must depart into the West, or dwindle to a rustic folk of dell and cave, slowly to forget and to be forgotten."

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 2 "The Shadow of The Past". "if [a mortal] often uses the Ring to make himself invisible, he fades: he becomes in the end invisible permanently, and walks in the twilight under the eye of the dark power that rules the Rings."

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 1 "Many Meetings". "You were in gravest peril while you wore the Ring, for then you were half in the wraith-world yourself."

- ^ The Silmarillion, pp. 18–20

- ^ The Silmarillion, p. 73

- ^ Morgoth's Ring I. "Notes on Motives in the Silmarillion"

- ^ Morgoth's Ring, "The Later Silmarillion", Part I

- ^ Morgoth's Ring, pp. 400 and passim

- ^ Carpenter 1981, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

- ^ Morgoth's Ring, "Myths Transformed", section VII

- ^ The Silmarillion, ch. 13 "Of the Return of the Noldor"

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Silmarillion, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- ^ The Silmarillion, index entry "Eldar"

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Silmarillion, ch. 1 "Of the Beginning of Days"

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Silmarillion, ch. 11 "Of the Sun and Moon and the Hiding of Valinor"

- ^ The Lost Road and Other Writings (1987), p. 43.

- ^ Sauron Defeated, p. 247

- ^ The Book of Lost Tales, "The Coming of the Valar"

- ^ The Return of the King. Tolkien defines Anor and Durin's Crown (under 'Star') in Index IV and Menelvagor and Ithil in Appendix E.I in the entries for 'H' and 'TH' consonant sounds respectively.

- ^ "Qenya Lexicon". Parma Eldalamberon. 12: 83.

- ^ The Return of the King, Appendix E. I, TH}}

- ^ Morgoth's Ring, Index

- ^ The War of the Jewels, "The Later Quenta Silmarillion"

- ^ The Silmarillion, "Of the Voyage of Eärendil"

- ^ Letters, #297

- ^ The Book of Lost Tales, Appendix, "Ingil"

- ^ The Silmarillion, Index. The index entries for Helluin and Wilwarin cite Sirius and Cassiopeia.

- ^ The Book of Lost Tales, Appendix, Morwinyon}}

- ^ "Qenya Lexicon". Parma Eldalamberon. 12. The twelfth volume of the linguistic journal Parma Eldalamberon published the complete text of Tolkien's Qenya Lexicon, including star names listed in entries omitted from The Book of Lost Tales appendix. These additional entries can be found on pages 35, 43, 63, and 82.

- ^ The Book of Lost Tales, Appendix, Telimektar

- ^ "Qenya Lexicon". Parma Eldalamberon. 12: 62.

- ^ The Return of the King, Appendix E.I, footnote

- ^ "Qenya Lexicon". Parma Eldalamberon. 12: 43.

- ^ The Book of Lost Tales, Appendix, "Gong"

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 3 "Three is Company"

- ^ The Silmarillion, Of the Coming of the Elves

- ^ Morgoth's Ring, The Later Quenta Silmarillion (I)

- ^ The Book of Lost Tales, Index IV, Star

- ^ The Lost Road and Other Writings, Etymologies, OT-

- ^ The Silmarillion, Of Beren and Lúthien

- ^ The Book of Lost Tales, The Coming of the Elves

- ^ The Lays of Beleriand, The Lay of Leithian, A.379

- ^ The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch. 10 "Strider"

- ^ The Silmarillion, Index

Secondary[]

- ^ Kilby, Clyde S. Tolkien & The Silmarillion. Harold Shaw, 1976, p. 59. "Tolkien admitted to Clyde Kilby in the summer of 1966 that this was the Holy Spirit. The nature of the Second Person of the Trinity, the Logos, appears ony in the abstract in the story 'Athrabeth Finrod Ah Andreth' ... anticipat[ing] the Incarnation. 'They say that the One will enter himself into Arda, and heal Men and all the Marring from the beginning to the end'". Bradley J. Birzer, "Eru" in Michael D. C. Drout (ed.), J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, 2007, p. 171.

- ^ Dickerson, Matthew (2013). "The Hröa and Fëa of Middle-Earth". In Christopher Vaccaro (ed.). The Body in Tolkien's Legendarium: Essays on Middle-earth Corporeality. McFarland. p. 78. OCLC 1001633828.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). The Lost Straight Road: HarperCollins. pp. 324–328. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- ^ Bolintineanu, Alexandra (2013). "Arda". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Kocher, Paul (1974) [1972]. Master of Middle-Earth: The Achievement of J.R.R. Tolkien. Penguin Books. pp. 8–11. ISBN 0140038779.

- ^ Lee, Stuart D.; Solopova, Elizabeth (2005). The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature Through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Palgrave. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-1403946713.

- ^ Larsen, Kristine, "A Little Earth of His Own: Tolkien's Lunar Creation Myths." In The Ring Goes Ever On: Proceedings of the Tolkien 2005 Conference, Vol. 2, ed. Sarah Wells. The Tolkien Society, 394–403, 2008.

- ^ Kristine Larsen, "Sea Birds and Morning Stars: Ceyx, Alcyone, and the Many Metamorphoses of Eärendil and Elwing." In Tolkien and the Study of His Sources: Critical Essays, ed. Jason Fisher, McFarland Publishers, 69–83, 2011.

- ^ Larsen, Kristine, "Red Comets and Red Stars: Tolkien, Martin, and the Use of Astronomy in Fantasy Series.", Proceedings of the 2nd Mythgard Institute Mythmoot, ed. Kris Swank. Mythgard Institute. 2014 (mythgard.org Archived 2015-03-21 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Larsen, Kristine (2005). "A Definitive Identification of Tolkien's 'Borgil': An Astronomical and Literary Approach". Tolkien Studies. West Virginia University Press. 2: 161–170. doi:10.1353/tks.2005.0023. In The Fellowship of the Ring, "Three is Company", Tolkien indicates that Borgil is a red star which appears over the horizon after Remmirath (Pleiades) and before Menelvagor (Orion). Larsen and others note that Aldebaran is known as 'the follower' of the Pleiades and is the only major red star to fit the description.

- ^ Manning, Jim; Taylor Planetarium (2003). "Elvish Star Lore" (PDF). The Planetarian (14). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-20.

Sources[]

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-31555-7

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Fellowship of the Ring, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08254-4

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Two Towers, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08254-4

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955), The Return of the King, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08256-0

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Silmarillion, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-25730-1

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1993), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), Morgoth's Ring, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-68092-1

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Book of Lost Tales, 1, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-35439-0

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Lost Road and Other Writings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-45519-7

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1985), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Lays of Beleriand, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-39429-5

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1992), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), Sauron Defeated, Boston, New York, & London: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-60649-7

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1994), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The War of the Jewels, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-71041-3

- Middle-earth theology

- Mythopoeia