Tuor and Idril

| Tuor | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien character | |

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases | Eladar, Ulmondil, 'The Blessed' |

| Race | Men |

| Book(s) | The Silmarillion Unfinished Tales The Book of Lost Tales II The Fall of Gondolin |

| Idril | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien character | |

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases | Celebrindal |

| Race | Elf |

| Book(s) | The Silmarillion Unfinished Tales The Book of Lost Tales II The Fall of Gondolin |

Tuor Eladar and Idril Celebrindal are fictional characters from J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth legendarium. They are the parents of Eärendil the Mariner and grandparents of Elrond Half-elven: through their progeny, they became the ancestors of the Númenoreans and of the King of the Reunited Kingdom Aragorn Elessar. Both characters play a pivotal role in The Fall of Gondolin, one of Tolkien's earliest stories which formed the basis for a section in his later work, The Silmarillion, and later expanded and released as a standalone publication in 2018.

Tuor and Idril were one of only three married unions between Men and Eldarin Elves in Tolkien's writings. Commentators have analyzed their depictions in Tolkien's narrative: comparisons were made to some of the major figures of the Trojan War in Greek mythology, as well as questions concerning the notion of death and immortality within Christian religious doctrine.

Etymology[]

In Tolkien's fictional language of Sindarin, the name Idril was a form of the name Itarillë (or Itarildë), which means "sparkling brilliance" in Quenya, another of Tolkien's invented languages. Tolkien also used the short form Itaril.[T 1] The name Celebrindal means 'Silverfoot': according to the early Sketch of the Mythology (the first version of the Silmarillion from 1926), she was so named "for the whiteness of her foot; and she walked and danced ever unshod in the white ways and green lawns of Gondolin." Tolkien describes her thus in this text: 'Very fair and tall was she, well nigh of warrior's stature, and her hair was a fountain of gold.' Christopher Tolkien comments that this description may be the prototype of that of Galadriel.[T 2] This is also present in the earliest form of the story The Fall of Gondolin, in which "the people called her Idril of the Silver Feet in that she went ever barefoot and bareheaded, king's daughter as she was, save only at pomps of the Ainur"; then she is called Talceleb or Taltelepta.[T 3]

Fictional history[]

Tuor Eladar, also known as Ulmondil or 'The Blessed', is the central character of The Fall of Gondolin.[1] He was a great hero of the Third House of Men in the First Age, the only son of Huor and Rían and the cousin of Túrin Turambar. Huor was slain covering the retreat of Turgon, King of Gondolin, in the Nírnaeth Arnoediad. Rían, having received no tidings of her husband, became distraught and wandered into the wild. She was taken care of by the local Grey-elves, and before the end of the year she bore a son and called him Tuor. But she delivered him to the care of the Elves and departed, dying upon the Haudh-en-Ndengin.[T 3]

Tuor was fostered by the Elves in the caves of Androth in the Mountains of Mithrim, in the Hithlum region of Beleriand, living a hard and wary life. When Tuor was sixteen their leader Annael resolved to forsake the land, but during the march his people were scattered and Tuor was captured by the Easterlings, who had been sent there by Morgoth and who cruelly oppressed the remnant of the House of Hador. After three years of thraldom under Lorgan the Easterling, Tuor escaped and returned to the caves.[T 3]

For four years he lived as an outlaw, but never saw a way of escape from Dor-lómin; he slew many of the Easterlings that he came upon during his journeys, and Tuor's name was feared. Meanwhile, Ulmo, Vala of Waters, heard of his plight and chose Tuor to bear a message to Turgon, Lord of the Hidden City of Gondolin, and give a hope for the Elves and Men. By Ulmo's power a spring near Tuor's cave overflowed, and following the stream Tuor passed through Dor-lómin to Ered Lómin. Under the guidance of two Elves sent there by Ulmo, Gelmir and Arminas, he passed through the ancient Gate of the Noldor (Sindarin Annon-in-Gelydh) into Nevrast, where Tuor is said to have been the first Man to come to the shore of the Great Sea, Belegaer. Thence he was led by seven swans, and came at last to the old dwellings of Turgon at Vinyamar.[T 3]

Tuor found arms and armour in the ruins of Vinyamar left there centuries ago by Turgon at the command of Ulmo, and then met Ulmo himself at the coast of Belegaer. He appointed Tuor to be his messenger and told him to seek King Turgon in Gondolin, and sent him the Elf Voronwë, saved by Ulmo from a shipwreck, to guide him. Voronwë led Tuor along the southern slopes of Ered Wethrin, and they caught a brief glimpse of Tuor's cousin Túrin near the Pools of Ivrin, the only time the paths of the two ever crossed. Journeying through the fell winter, they eventually reached the hidden city of Gondolin and were admitted; but Turgon refused to abandon Gondolin.[T 3]

Tuor remained and fell in love with the only child of Turgon, Idril Celebrindal, whose mother Elenwë died during the crossing of the Helcaraxë. In contrast to the first union of Elves and Men, that between Lúthien and Beren which required much hardship and unimaginable sacrifice, Tuor and Idril were allowed to marry without difficulty; their wedding was celebrated with great mirth and joy. This was because King Turgon had grown fond of Tuor, who was made the leader of the House of the Swan Wing, one of the twelve houses of Gondolin. Turgon also remembered the last words of Huor which prophesied that a "star" would arise out of both his and Turgon's lineage which would redeem the Children of Ilúvatar from Morgoth. This was the second union between the Elves and Men. However, their marriage angered Turgon's influential nephew Maeglin, who desired Idril for himself. Maeglin defied Turgon's order to stay within the mountains, and unbeknownst to the people of Gondolin was captured by Orcs during a trip to gather resources. Having noticed Maeglin's suspicious behaviour, who said nothing about his encounter with Morgoth and his servants upon his return, Idril decided to construct a secret passage out of Gondolin, known as Idril's Secret Way.[T 3]

During the sack of Gondolin, Tuor defended Idril and their only child Eärendil from Orcs and the traitorous Maeglin, who was promised both Gondolin and Idril by Morgoth in return for the location of the hidden city and threatened to murder the child by throwing him over the edge of the city wall. After Maeglin's death, they led a remnant of the people of Gondolin to escape the sacking of the city by Idril's Secret Way, but encountered in the mountain heights a Balrog, who was defeated by the valour and self-sacrifice of Glorfindel, chief of the House of the Golden Flower. They eventually reached Nan-tathren and the Mouths of Sirion.[T 3]

Longing for the Sea, Tuor built the ship Eärramë ("Sea-wing"). The Mouths of Sirion were now held by Eärendil and his wife Elwing, but Tuor sailed to the West with Idril, and it was a tradition under the Eldar and Edain that they arrived in Valinor, bypassing the Ban of the Valar, and that Tuor alone of Men was counted among Elven kindred. Eärendil inherits from Idril Elessar, a magical green gem which bestowed healing powers on those who touch it; it is passed down to their descendant Aragorn by the end of the Third Age and gives the returned king his regnal name.[2][3] Eärendil would later become the saviour of Elves and Men and their mediator to the Valar, instigating the War of Wrath against Morgoth which ultimately led to the Dark Lord's defeat by the Hosts of the Valar at the conclusion of the First Age.[T 3]

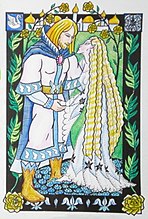

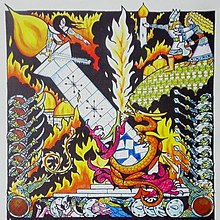

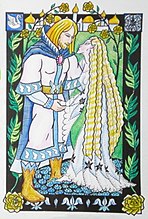

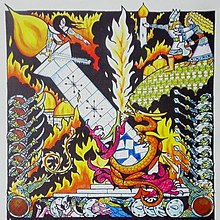

- Illustrations by Tom Loback, 2007

The wedding of Tuor and Idril

The collapse of Turgon’s tower

Battle for Gondolin:

Tuor kills the orc Othrod

Family tree[]

| Half-elven family tree[T 4][T 5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Concept and creation[]

The story of Tuor and Idril is one of many told briefly in the 23rd chapter of The Silmarillion, which recounts the fall of the Noldorin city of Gondolin.[T 3] A very early version, written circa 1916–17, is found in The Book of Lost Tales II,[T 6] part of The History of Middle-earth. Unfinished Tales contains the start of a more mature and complete narrative, which Tolkien began after finishing The Lord of the Rings in the 1950s. However, it gets no further than Tuor's first sight of Gondolin.[T 7] In some texts Tolkien spells his name Tûr, but finally decided on Tuor.

In the original Fall of Gondolin story, Tuor is said to have carried an axe, called Dramborleg "Thudder-Sharp", that "smote both a heavy dint as of a club and cleft as a sword". The Axe of Tuor is referred to in later writings as preserved in Númenor as an heirloom of the Kings, though the name must have been rejected as unfitting later language conceptions.[T 8]

In early versions of the story Tuor was supposed to have travelled all the way from Dor-lómin along the shores of the Sea to the Mouths of Sirion. There he met Voronwë (or "Bronweg"), and in Nan-tathren Ulmo appeared to them. The journey to Gondolin was thus up the River Sirion.

Analysis[]

Tuor[]

Samuel Cook, writing in Anor, stated the case for Tuor as a forgotten hero, and that it is "a matter of opinion" as to whether his feats measure up to other heroes found in Tolkien's works like the better-known Beren and Túrin.[4] Cook noted that while Tuor received assistance from Glorfindel and Idril, he fulfilled his part in the narrative, such as defeating Maeglin in single combat.[4] Lisa Coutras noted that Tuor demonstrated wisdom by listening to his wife, whose wise counsel is her defining trait, whereas a leader of greater stature like Thingol, the Elvenking of Doriath, was brought low by his recklessness and pride.[5]

Jennifer Rogers notes in Tolkien Studies that Christopher Tolkien, in his book The Fall of Gondolin, seamlessly, without the editorial apparatus used in The History of Middle-earth, introduces the story by providing short extracts of his father's 1926 "Sketch of the Mythology" and "The Flight of the Noldoli from Valinor". She writes that these additions set "Tuor's story in the context of the Doom of Mandos and the Oath of Fëanor", in other words within the legendarium.[6]

Linda Greenwood, in Tolkien Studies, notes that Tuor is the only mortal Man in the legendarium who is permitted, with his Elvish wife Idril, to live as an immortal, something not otherwise allowed.[7][8] Tolkien suggests an explanation in a letter, namely that Eru Ilúvatar, the One God, directly intervenes as a unique exception, just as in Lúthien's assumption of a mortal fate.[T 9]

David Greenman, in Mythlore, compares The Fall of Gondolin, Tolkien's first long Middle-earth work, to Virgil's Aeneid. He finds it fitting that Tuor, "Tolkien's early quest-hero", escapes from the wreck of an old kingdom and creates new ones, just as Aeneas does, while his late quest-heroes in The Lord of the Rings, the hobbits of the Shire, are made to return to their home, ravaged while they were away, and are obliged to scour it clean, just as Odysseus does in Homer's Odyssey.[9]

John Garth writes in his book Tolkien's Worlds that the windswept treeless hills of Nevrast, where Tuor reaches the cliffs and becomes the first Man to see the sea in the legendarium, are "perfectly Cornish". Garth notes that Tuor stands there, arms outspread at sunset, until the sea-Vala Ulmo appears from the water to prophesy the birth of Tuor's son Earendil, who ends up with a Silmaril in the sky as the Evening Star.[10] The German artist Jenny Dolfen has painted the scene in her 2019 "And His Heart Was Filled With Longing" as a Cornish landscape, with Tuor surrounded by seagulls.[10][11] He points out that this means that the Evening Star was not in the western sky that Tuor saw, whereas when Tolkien visited the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall in 1914, the planet had risen and set "due west", an uncommon sight. A few weeks later, Tolkien wrote the first poem of his legendarium, "The Voyage of Earendel the Evening Star".[10]

Idril[]

Melanie Rawls identified Idril as a female character with agency in Tolkien's works: she is shown to be capable of taking action once she has achieved understanding.[12] Idril counsels her father, Turgon, who "is very masculine and in need of a feminine counterpart", in his rule of Gondolin. Rawls states, too, that Idril is a "well-balanced personality", and that Tuor, who combines masculine (warrior) and feminine (counsellor) qualities, "matches her well"..[12] In Tor.com's series on the people of Middle-earth, Megan N. Fontenot praised the characterisation of Idril's wisdom and forbearance as told in the story of the Fall of Gondolin. In Fontenot's view, Idril's story represented "a significant milestone in Tolkien's storytelling career", as she saw in it many echoes of several other female characters of Middle-earth.[2]

Greenman compared and contrasted Idril's part in the story to Cassandra and Helen of Troy, two prominent female figures in accounts of the Trojan War: like the prophetess, Idril had a premonition of impending danger and like Helen, her beauty played a major role in instigating Maeglin's betrayal of Gondolin, which ultimately led to its downfall and ruin. Conversely, Greeman noted that Idril's advice to enact a contingency plan for a secret escape route out of Gondolin was heeded by her people, and that she had always rejected Maeglin's advances and remained faithful to Tuor.[9]

Influence[]

Tolkien suspected that his fellow writer and friend C.S. Lewis had borrowed his ideas; he felt that the characters of Tor and Tinidril in Lewis' Perelandra or Voyage to Venus had a "certain echo of Tuor and Idril", and that Tinidril in particular was a pastiche of both Idril and Tinúviel, an earlier version of his Lúthien character.[13]

A species of moth, Elachista tuorella, was named after Tuor by Finnish entomologist Lauri Kaila.[14]

Adaptations[]

In Peter Jackson's film adaptations of Tolkien's Middle-earth, Idril is referenced as the original owner of the sword Hadhafang, an original invention by the affiliated production company Weta Workshop.[15] It is wielded by Idril's descendants Elrond and Arwen in certain scenes of both The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit film series.[16]

References[]

Primary[]

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Peoples of Middle-earth, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, "The Shibboleth of Fëanor"., ISBN 0-395-82760-4

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1986), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Shaping of Middle-earth, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, The Earliest 'Silmarillion', ISBN 0-395-42501-8

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Silmarillion, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, Ch. 23, "Of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin", ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2

- ^ The Silmarillion, "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age": Family Trees I and II: "The house of Finwë and the Noldorin descent of Elrond and Elros", and "The descendants of Olwë and Elwë"

- ^ The Return of the King, Appendix A: Annals of the Kings and Rulers, I The Númenórean Kings

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1984), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Book of Lost Tales, 2, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, "The Fall of Gondolin", ISBN 0-395-36614-3

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), Unfinished Tales, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, "Of Tuor and his Coming to Gondolin", ISBN 0-395-29917-9

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), Unfinished Tales, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, "A Description of Númenor", note 2, ISBN 0-395-29917-9

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, #153 to Peter Hastings, September 1954, ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2

Secondary[]

- ^ Thomas, Paul Edmund (2013) [2007]. "Inklings". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ a b Fontenot, Megan (25 July 2019). "Exploring the People of Middle-earth: Idril the Far-Sighted, Wisest of Counsellors". Tor.com. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Drout, Michael D. C., ed. (2013) [2007]. "Elessar". J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ a b Cook, Samuel (2017). "In Defence of Tuor" (PDF). Anor (52 Michaelmas 2017): 22–25.

- ^ Coutras, Lisa (2016). Tolkien’s Theology of Beauty: Majesty, Splendor, and Transcendence in Middle-earth. Springer. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-1375-5345-4.

- ^ Rogers, Jennifer (2019). "The Fall of Gondolin by J.R.R Tolkien". Tolkien Studies. 16 (1): 170–174. doi:10.1353/tks.2019.0013. ISSN 1547-3163.

- ^ Greenwood, Linda (2005). "Love: 'The Gift of Death'". Tolkien Studies. 2 (1): 171–195. doi:10.1353/tks.2005.0019. ISSN 1547-3163.

- ^ Biese, Mary (27 October 2020). "Tolkien and Immortality". Clarifying Catholicism. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Greenman, David (1992). "Aeneidic and Odyssean Patterns of Escape and Release in Tolkien's 'The Fall of Gondolin' and 'The Return of the King'". Mythlore. 18 (2). Article 1.

- ^ a b c Garth, John (2020). Tolkien's worlds : the places that inspired the writer's imagination. London: White Lion Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-7112-4127-5. OCLC 1181910875.

- ^ Dolfen, Jenny (2019). "And His Heart Was Filled With Longing". Twitter. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b Rawls, Melanie (2015). "The Feminine Principle in Tolkien". In Croft, Janet Brennan; Donovan, Leslie A. (eds.). Perilous and Fair: Women in the Works and Life of J. R. R. Tolkien. Mythopoeic Press. pp. 99–117. ISBN 978-1-887726-01-6. OCLC 903655969.

- ^ Cawthorne, Nigel (2012). A Brief Guide to J. R. R. Tolkien: A comprehensive introduction to the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. London: Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-7803-3860-6.

- ^ Kaila, Lauri (1999). "A Revision of the Nearctic Species of the Genus Elachista s. l. III.: The bifasciella, praelineata, saccharella and freyerella groups (Lepidoptera, Elachistidae)". Acta Zoologica Fennica (211): 1–235.

- ^ Derdzinski, Ryszard, ed. (2002). "Language in the Lord of the Rings movie". Archived from the original on 11 August 2002. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ "Lord Elrond of Rivendell: Dol Guldur - Weta Workshop". Weta Workshop. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- Middle-earth Edain

- Middle-earth Elves

- Characters in The Silmarillion

- Fictional married couples

- Fictional outlaws

- Literary characters introduced in 1977