Critical mass (sociodynamics)

In social dynamics, critical mass is a sufficient number of adopters of a new idea, technology or innovation in a social system so that the rate of adoption becomes self-sustaining and creates further growth. The point at which critical mass is achieved is sometimes referred to as a threshold within the threshold model of statistical modeling.

The term critical mass is borrowed from nuclear physics and in that field, it refers to the amount of a substance needed to sustain a chain reaction. Within social sciences, critical mass has its roots in sociology and is often used to explain the conditions under which reciprocal behavior is started within collective groups, and how it becomes self-sustaining. Recent technology research in platform ecosystems shows that apart from the quantitative notion of a “sufficient number” critical mass is also influenced by qualitative properties such as reputation, interests, commitments, capabilities, goals, consensuses, and decisions, all of which are crucial in determining whether reciprocal behavior can be started to achieve sustainability to a commitment such as an idea, new technology, or innovation.[1][2]

Other social factors that are important include the size, inter-dependencies and level of communication in a society or one of its subcultures. Another is social stigma, or the possibility of public advocacy due to such a factor. Critical mass is a concept used in a variety of contexts, including physics, group dynamics, politics, public opinion, and technology.

History[]

The concept of critical mass was originally created by game theorist Thomas Schelling and sociologist Mark Granovetter to explain the actions and behaviors of a wide range of people and phenomenon. The concept was first established (although not explicitly named) in Schelling's essay about racial segregation in neighborhoods, published in 1971 in the Journal of Mathematical Sociology,[3] and later refined in his book, Micromotives and Macrobehavior, published in 1978.[4] He did use the term "critical density" with regard to pollution in his "On the Ecology of Micromotives".[5] Mark Granovetter, in his essay "Threshold models of collective behavior", published in the American Journal of Sociology in 1978[6] worked to solidify the theory.[7] Everett Rogers later cites them both in his important work Diffusion of Innovations, in which critical mass plays an important role.

Predecessors[]

The concept of critical mass had existed before it entered a sociology context. It was an established concept in medicine, specifically epidemiology, since the 1920s, as it helped to explain the spread of illnesses.

It had also been a present, if not solidified, idea in the study of consumer habits and economics, especially in General Equilibrium Theory. In his papers, Schelling quotes the well-known "The Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism" paper written in 1970 by George Akerlof.[8] Similarly, Granovetter cited the Nash Equilibrium game in his papers.

Finally, Herbert A. Simon's essay, "Bandwagon and underdog effects and the possibility of election predictions", published in 1954 in Public Opinion Quarterly,[9] has been cited as a predecessor to the concept we now know as critical mass.

Logic of collective action and common good[]

Critical mass and the theories behind it help us to understand aspects of humans as they act and interact in a larger social setting. Certain theories, such as Mancur Olson's Logic of Collective Action[10] or Garrett Hardin's Tragedy of the Commons,[11] work to help us understand why humans do or adopt certain things which are beneficial to them, or, more importantly, why they do not. Much of this reasoning has to do with individual interests trumping that which is best for the collective whole, which may not be obvious at the time.

Oliver, Marwell, and Teixeira tackle this subject in relation to critical theory in a 1985 article published in the American Journal of Sociology.[12] In their essay, they define that action in service of a public good as "collective action". "Collective Action" is beneficial to all, regardless of individual contribution. By their definition, then, "critical mass" is the small segment of a societal system that does the work or action required to achieve the common good. The "Production Function" is the correlation between resources, or what individuals give in an effort to achieve public good, and the achievement of that good. Such function can be decelerating, where there is less utility per unit of resource, and in such a case, resource can taper off. On the other hand, the function can be accelerating, where the more resources that are used the bigger the payback. "Heterogeneity" is also important to the achievement of a common good. Variations (heterogeneity) in the value individuals put on a common good or the effort and resources people give is beneficial, because if certain people stand to gain more, they are willing to give or pay more.

Gender politics[]

Critical mass theory in gender politics and collective political action is defined as the critical number of personnel needed to affect policy and make a change not as the token but as an influential body.[13] This number has been placed at 30%, before women are able to make a substantial difference in politics.[14][15] However, other research suggests lower numbers of women working together in legislature can also affect political change.[16][17] Kathleen Bratton goes so far as to say that women, in legislatures where they make up less than 15% of the membership, may actually be encouraged to develop legislative agendas that are distinct from those of their male colleagues.[18] Others argue that we should look more closely at parliamentary and electoral systems instead of critical mass.[19][20]

Interactive media[]

While critical mass can be applied to many different aspects of sociodynamics, it becomes increasingly applicable to innovations in interactive media such as the telephone, fax, or email. With other non-interactive innovations, the dependence on other users was generally sequential, meaning that the early adopters influenced the later adopters to use the innovation. However, with interactive media, the interdependence was reciprocal, meaning both users influenced each other. This is due to the fact that interactive media have high network effect,[21] where in the value and utility of a good or service increases the more users it has. Thus, the increase of adopters and quickness to reach critical mass can therefore be faster and more intense with interactive media, as can the rate at which previous users discontinue their use. The more people that use it, the more beneficial it will be, thus creating a type of snowball effect, and conversely, if users begin to stop using the innovation, the innovation loses utility, thus pushing more users to discontinue their use.[22]

Markus essay[]

In M. Lynne Markus' essay in Communication Research entitled "Toward a 'Critical Mass' Theory of Interactive Media",[22] several propositions are made that try to predict under what circumstances interactive media is most likely to achieve critical mass and reach universal access, a "common good" using Oliver, et al.'s terminology. One proposition states that such media's existence is all or nothing, where in if universal access is not achieved, then, eventually, use will discontinue. Another proposition suggests that a media's ease of use and inexpensiveness, as well as its utilization of an "active notification capability" will help it achieve universal access. The third proposition states that the heterogeneity, as discussed by Oliver, et al. is beneficial, especially if users are dispersed over a larger area, thus necessitating interactivity via media. Fourth, it is very helpful to have highly sought-after individuals to act as early adopters, as their use acts as incentive for later users. Finally, Markus posits that interventions, both monetarily and otherwise, by governments, businesses, or groups of individuals will help a media reach its critical mass and achieve universal access.

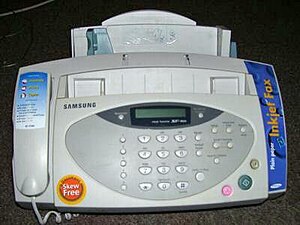

Fax machine example[]

An example put forth by Rogers in Diffusion of Innovations was that of the fax machine, which had been around for almost 150 years before it became popular and widely used. It had existed in various forms and for various uses, but with more advancements in the technology of faxes, including the use of existing phone lines to transmit information, coupled with falling prices in both machines and cost per fax, the fax machine reached a critical mass in 1987, when "Americans began to assume that 'everybody else' had a fax machine".[23]

Social media example[]

Critical mass is fundamental for social media sites to maintain a significant userbase. Reaching a sustainable population is dependent on the collective use of the technology rather than the individual’s use. The adoption of the platform creates the effects of positive externalities whereby each additional user provides additional perceived benefits to previous and potential adopters. [24]

Facebook provides a good illustration of critical mass. The initial stages of Facebook had limited value to users due to the lack of network effects and critical mass. [25] The principle behind the strategy is that at each time Facebook enlarged the size of the community, the saturation never drops below the critical mass, reaching the desired diffusion effect discussed in Rogers, Diffusion of innovations.[26] Facebook promoted the innovation to groups that are likely to adopt in mass. Between 2003-2004 Facebook was exclusive to universities such as Harvard, Yale and 34 other schools. Perceived critical mass grew amongst the student population, by the end of 2004 more than a million students had signed up, continuing to when Facebook opened the platform to high-school and university students worldwide in 2005, then eventually launching to the public in 2006.[27] By obtaining critical mass in each relative population before advancing to the next audience, Facebook developed enough saturation to become self-sustaining. Becoming self-sustained helps grow and maintain network size, whilst also enhancing the perceived critical mass of those yet to adopt.

See also[]

- Bandwagon effect

- Network effect

- One-third hypothesis

- Positive feedback

- Tipping point (sociology)

- Viral phenomenon

- Metcalfe's law

References[]

- ^ Evans, D. S., & Schmalensee, R. (2010). “Failure to launch: Critical mass in platform businesses.” Review of Network Economics, 9(4), 1-33.

- ^ David, R., Aubert, B.A., Bernard, J-G., & Luczak-Roesch, M. (2020). Critical Mass in Inter-Organizational Platforms. Americas Conference of Information Systems (AMCIS), Salt Lake City, UT. 10-12 August, 2020. https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1055&context=amcis2020

- ^ Schelling, Thomas C. (1971). "Dynamic models of segregation". The Journal of Mathematical Sociology. Informa UK Limited. 1 (2): 143–186. doi:10.1080/0022250x.1971.9989794. ISSN 0022-250X.

- ^ Schelling, Thomas C. Micromotives and Macrobehavior. New York: Norton, 1978. Print.

- ^ Schelling, Thomas C. "On the Ecology of Micromotives," The Public Interest, No. 25, Fall 1971.

- ^ Granovetter, Mark (1978). "Threshold Models of Collective Behavior". American Journal of Sociology. 83 (6): 1420. doi:10.1086/226707. S2CID 49314397.

- ^ Krauth, Brian. "Notes for a History of the Critical Mass Model." SFU.ca. Web. 29 November 2011. https://www.sfu.ca/~bkrauth/papers/critmass.htm.

- ^ Akerlof, George A. The Market for "lemons": Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. 2003. Print.

- ^ Kuran, Timur (1987). "Chameleon Voters and Public Choice". Public Choice. 53 (1): 53–78. doi:10.1007/bf00115654. S2CID 154483266.

- ^ Olson, Mancur. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1971. Print.

- ^ Hardin, G (1968). "The Tragedy of the Commons". Science. 162 (3859): 1243–248. Bibcode:1968Sci...162.1243H. doi:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243. PMID 5699198.

- ^ Oliver, P.; Marwell, G.; Teixeira, R. (1985). "A Theory of Critical Mass: I. Interdependence, Group Heterogeneity, and the Production of Collective Action". American Journal of Sociology. 91 (3): 522–56. doi:10.1086/228313. S2CID 16390125.

- ^ Kanter, Rosabeth Moss (March 1977). "Some effects of proportions on group life: skewed sex ratios and responses to token women". American Journal of Sociology. 82 (5): 965–990 for the University of Chicago Press. doi:10.1086/226425. JSTOR 2777808. S2CID 144140263. Pdf from Norges Handelshøyskole (NHH), the Norwegian School of Economics. Archived 28 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dahlerup, Drude (December 1988). "From a small to a large minority: women in Scandinavian politics". Scandinavian Political Studies. 11 (4): 275–297. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9477.1988.tb00372.x.

- ^ Dahlerup, Drude (December 2006). "The story of the theory of critical mass". Politics & Gender. 2 (4): 511–522. doi:10.1017/S1743923X0624114X.

- ^ Childs, Sarah; Krook, Mona Lena (December 2006). "Should feminists give up on critical mass? A contingent yes". Politics & Gender. 2 (4): 522–530. doi:10.1017/S1743923X06251146.

- ^ Childs, Sarah; Krook, Mona Lena (October 2008). "Critical mass theory and women's political representation". Political Studies. 56 (3): 725–736. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00712.x. Pdf.

- ^ Bratton, Kathleen A. (March 2005). "Critical mass theory revisited: the behavior and success of token women in state legislatures". Politics & Gender. 1 (1): 97–125. doi:10.1017/S1743923X0505004X.

- ^ Tremblay, Manon (December 2006). "The substantive representation of women and PR: some reflections on the role of surrogate representation and critical mass". Politics & Gender. 2 (4): 502–511. doi:10.1017/S1743923X06231143.

- ^ Grey, Sandra (December 2006). "Numbers and beyond: the relevance of critical mass in gender research". Politics & Gender. 2 (4): 492–502. doi:10.1017/S1743923X06221147.

- ^ Rogers, Everett M. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003. Print.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Markus, M. Lynne (1987). "Toward a "Critical Mass" Theory of Interactive Media: Universal Access, Interdependence and Diffusion". Communication Research. SAGE Publications. 14 (5): 491–511. doi:10.1177/009365087014005003. ISSN 0093-6502. S2CID 57147797.

- ^ Holmlov, Kramer and Karl-Eric Warneryd (1990). Adoption and Use of Fax in Sweden. Elmservier Science.

- ^ Rauniar, Rupak; Rawski, Greg; Yang, Jei; Johnson, Ben (4 February 2014). "Technology acceptance model (TAM) and social media usage: an empirical study on Facebook". Journal of Enterprise Information Management. 27 (1): 6–30. doi:10.1108/JEIM-04-2012-0011. ISSN 1741-0398.

- ^ Van Slyke, Craig; Ilie, Virginia; Lou, Hao; Stafford, Thomas (2007). "Perceived critical mass and the adoption of a communication technology". European Journal of Information Systems. 16 (3): 270-283. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000680. S2CID 12566191.

- ^ "DIFFUSION OF INNOVATIONS. By Everett M. Rogers. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1962. 367". Social Forces. 41 (4): 415–416. 1 May 1963. doi:10.2307/2573300. ISSN 0037-7732. JSTOR 2573300.

- ^ "Facebook | Overview, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

Further reading[]

- Philip Ball: Critical Mass: How One Thing Leads to Another, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 0-374-53041-6

- Mancur Olson: The Logic of Collective Action, Harvard University Press, 1971

- Motion (physics)

- Social systems

- Systems theory

- Social dynamics