Politics

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

Politics (from Greek: Πολιτικά, politiká, 'affairs of the cities') is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations between individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies politics and government is referred to as political science.

It may be used positively in the context of a "political solution" which is compromising and non-violent,[1] or descriptively as "the art or science of government", but also often carries a negative connotation.[2] For example, abolitionist Wendell Phillips declared that "we do not play politics; anti-slavery is no half-jest with us."[3] The concept has been defined in various ways, and different approaches have fundamentally differing views on whether it should be used extensively or limitedly, empirically or normatively, and on whether conflict or co-operation is more essential to it.

A variety of methods are deployed in politics, which include promoting one's own political views among people, negotiation with other political subjects, making laws, and exercising force, including warfare against adversaries.[4][5][6][7][8] Politics is exercised on a wide range of social levels, from clans and tribes of traditional societies, through modern local governments, companies and institutions up to sovereign states, to the international level. In modern nation states, people often form political parties to represent their ideas. Members of a party often agree to take the same position on many issues and agree to support the same changes to law and the same leaders. An election is usually a competition between different parties.

A political system is a framework which defines acceptable political methods within a society. The history of political thought can be traced back to early antiquity, with seminal works such as Plato's Republic and Aristotle's Politics in the West, and Confucius's political manuscripts and Chanakya's Arthashastra and Chanakya Niti in the East.[9]

Etymology[]

The English politics has its roots in the name of Aristotle's classic work, Politiká, which introduced the Greek term politiká (Πολιτικά, 'affairs of the cities'). In the mid-15th century, Aristotle's composition would be rendered in Early Modern English as Polettiques [sic],[a][10] which would become Politics in Modern English.

The singular politic first attested in English in 1430, coming from Middle French politique—itself taking from politicus,[11] a Latinization of the Greek πολιτικός (politikos) from πολίτης (polites, 'citizen') and πόλις (polis, 'city').[12]

Definitions[]

- In the view of Harold Lasswell, politics is "who gets what, when, how."[13]

- For David Easton, it is about "the authoritative allocation of values for a society."[14]

- To Vladimir Lenin, "politics is the most concentrated expression of economics."[15]

- Bernard Crick argued that "politics is a distinctive form of rule whereby people act together through institutionalized procedures to resolve differences, to conciliate diverse interests and values and to make public policies in the pursuit of common purposes."[16]

- According to Adrian Leftwich:

Politics comprises all the activities of co-operation, negotiation and conflict within and between societies, whereby people go about organizing the use, production or distribution of human, natural and other resources in the course of the production and reproduction of their biological and social life.[17]

Approaches[]

There are several ways in which approaching politics has been conceptualized.

Extensive and limited[]

Adrian Leftwich has differentiated views of politics based on how extensive or limited their perception of what accounts as 'political' is.[18] The extensive view sees politics as present across the sphere of human social relations, while the limited view restricts it to certain contexts. For example, in a more restrictive way, politics may be viewed as primarily about governance,[19] while a feminist perspective could argue that sites which have been viewed traditionally as non-political, should indeed be viewed as political as well.[20] This latter position is encapsulated in the slogan the personal is political, which disputes the distinction between private and public issues. Instead, politics may be defined by the use of power, as has been argued by Robert A. Dahl.[21]

Moralism and realism[]

Some perspectives on politics view it empirically as an exercise of power, while others see it as a social function with a normative basis.[22] This distinction has been called the difference between political moralism and political realism.[23] For moralists, politics is closely linked to ethics, and is at its extreme in utopian thinking.[23] For example, according to Hannah Arendt, the view of Aristotle was that "to be political…meant that everything was decided through words and persuasion and not through violence;"[24] while according to Bernard Crick "[p]olitics is the way in which free societies are governed. Politics is politics and other forms of rule are something else."[25] In contrast, for realists, represented by those such as Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hobbes, and Harold Lasswell, politics is based on the use of power, irrespective of the ends being pursued.[26][23]

Conflict and co-operation[]

Agonism argues that politics essentially comes down to conflict between conflicting interests. Political scientist Elmer Schattschneider argued that "at the root of all politics is the universal language of conflict,"[27] while for Carl Schmitt the essence of politics is the distinction of 'friend' from foe'.[28] This is in direct contrast to the more co-operative views of politics by Aristotle and Crick. However, a more mixed view between these extremes is provided by Irish political scientist Michael Laver, who noted that:

Politics is about the characteristic blend of conflict and co-operation that can be found so often in human interactions. Pure conflict is war. Pure co-operation is true love. Politics is a mixture of both.[29]

History[]

The history of politics spans human history and is not limited to modern institutions of government.

Prehistoric[]

Frans de Waal argued that already chimpanzees engage in politics through "social manipulation to secure and maintain influential positions."[30] Early human forms of social organization—bands and tribes—lacked centralized political structures.[31] These are sometimes referred to as stateless societies.

Early states[]

In ancient history, civilizations did not have definite boundaries as states have today, and their borders could be more accurately described as frontiers. Early dynastic Sumer, and early dynastic Egypt were the first civilizations to define their borders. Moreover, up to the 12th century, many people lived in non-state societies. These range from relatively egalitarian bands and tribes to complex and highly stratified chiefdoms.

State formation[]

There are a number of different theories and hypotheses regarding early state formation that seek generalizations to explain why the state developed in some places but not others. Other scholars believe that generalizations are unhelpful and that each case of early state formation should be treated on its own.[32]

Voluntary theories contend that diverse groups of people came together to form states as a result of some shared rational interest.[33] The theories largely focus on the development of agriculture, and the population and organizational pressure that followed and resulted in state formation. One of the most prominent theories of early and primary state formation is the hydraulic hypothesis, which contends that the state was a result of the need to build and maintain large-scale irrigation projects.[34]

Conflict theories of state formation regard conflict and dominance of some population over another population as key to the formation of states.[33] In contrast with voluntary theories, these arguments believe that people do not voluntarily agree to create a state to maximize benefits, but that states form due to some form of oppression by one group over others. Some theories in turn argue that warfare was critical for state formation.[33]

Ancient history[]

The first states of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from the Uruk period and Predynastic Egypt respectively around approximately 3000 BCE.[35] Early dynastic Egypt was based around the Nile River in the north-east of Africa, the kingdom's boundaries being based around the Nile and stretching to areas where oases existed.[36] Early dynastic Sumer was located in southern Mesopotamia with its borders extending from the Persian Gulf to parts of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.[35]

Although state-forms existed before the rise of the Ancient Greek empire, the Greeks were the first people known to have explicitly formulated a political philosophy of the state, and to have rationally analyzed political institutions. Prior to this, states were described and justified in terms of religious myths.[37]

Several important political innovations of classical antiquity came from the Greek city-states (polis) and the Roman Republic. The Greek city-states before the 4th century granted citizenship rights to their free population; in Athens these rights were combined with a directly democratic form of government that was to have a long afterlife in political thought and history.[citation needed]

Modern states[]

The Peace of Westphalia (1648) is considered by political scientists to be the beginning of the modern international system,[38][39][40] in which external powers should avoid interfering in another country's domestic affairs.[41] The principle of non-interference in other countries' domestic affairs was laid out in the mid-18th century by Swiss jurist Emer de Vattel.[42] States became the primary institutional agents in an interstate system of relations. The Peace of Westphalia is said to have ended attempts to impose supranational authority on European states. The "Westphalian" doctrine of states as independent agents was bolstered by the rise in 19th century thought of nationalism, under which legitimate states were assumed to correspond to nations—groups of people united by language and culture.[43]

In Europe, during the 18th century, the classic non-national states were the multinational empires: the Austrian Empire, Kingdom of France, Kingdom of Hungary,[44] the Russian Empire, the Spanish Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the British Empire. Such empires also existed in Asia, Africa, and the Americas; in the Muslim world, immediately after the death of Muhammad in 632, Caliphates were established, which developed into multi-ethnic trans-national empires.[45] The multinational empire was an absolute monarchy ruled by a king, emperor or sultan. The population belonged to many ethnic groups, and they spoke many languages. The empire was dominated by one ethnic group, and their language was usually the language of public administration. The ruling dynasty was usually, but not always, from that group. Some of the smaller European states were not so ethnically diverse, but were also dynastic states, ruled by a royal house. A few of the smaller states survived, such as the independent principalities of Liechtenstein, Andorra, Monaco, and the republic of San Marino.

Most theories see the nation state as a 19th-century European phenomenon, facilitated by developments such as state-mandated education, mass literacy, and mass media. However, historians[who?] also note the early emergence of a relatively unified state and identity in Portugal and the Dutch Republic.[46] Scholars such as Steven Weber, David Woodward, Michel Foucault, and Jeremy Black have advanced the hypothesis that the nation state did not arise out of political ingenuity or an unknown undetermined source, nor was it an accident of history or political invention.[47][33][48] Rather, the nation state is an inadvertent byproduct of 15th-century intellectual discoveries in political economy, capitalism, mercantilism, political geography, and geography[49][50] combined with cartography[51][52] and advances in map-making technologies.[53]

Some nation states, such as Germany and Italy, came into existence at least partly as a result of political campaigns by nationalists, during the 19th century. In both cases, the territory was previously divided among other states, some of them very small. Liberal ideas of free trade played a role in German unification, which was preceded by a customs union, the Zollverein. National self-determination was a key aspect of United States President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, leading to the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire after the First World War, while the Russian Empire became the Soviet Union after the Russian Civil War. Decolonization lead to the creation of new nation states in place of multinational empires in the Third World.

Globalization[]

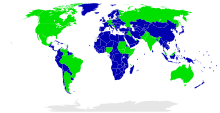

Political globalization began in the 20th century through intergovernmental organizations and supranational unions. The League of Nations was founded after World War I, and after World War II it was replaced by the United Nations. Various international treaties have been signed through it. Regional integration has been pursued by the African Union, ASEAN, the European Union, and Mercosur. International political institutions on the international level include the International Criminal Court, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization.

Political science[]

This section does not cite any sources. (December 2020) |

The study of politics is called political science, or politology. It comprises numerous subfields, including comparative politics, political economy, international relations, political philosophy, public administration, public policy, gender and politics, and political methodology. Furthermore, political science is related to, and draws upon, the fields of economics, law, sociology, history, philosophy, geography, psychology/psychiatry, anthropology, and neurosciences.

Comparative politics is the science of comparison and teaching of different types of constitutions, political actors, legislature and associated fields, all of them from an intrastate perspective. International relations deals with the interaction between nation-states as well as intergovernmental and transnational organizations. Political philosophy is more concerned with contributions of various classical and contemporary thinkers and philosophers.

Political science is methodologically diverse and appropriates many methods originating in psychology, social research, and cognitive neuroscience. Approaches include positivism, interpretivism, rational choice theory, behavioralism, structuralism, post-structuralism, realism, institutionalism, and pluralism. Political science, as one of the social sciences, uses methods and techniques that relate to the kinds of inquiries sought: primary sources such as historical documents and official records, secondary sources such as scholarly journal articles, survey research, statistical analysis, case studies, experimental research, and model building.

Political system[]

The political system defines the process for making official government decisions. It is usually compared to the legal system, economic system, cultural system, and other social systems. According to David Easton, "A political system can be designated as the interactions through which values are authoritatively allocated for a society."[14] Each political system is embedded in a society with its own political culture, and they in turn shape their societies through public policy. The interactions between different political systems are the basis for global politics.

Forms of government[]

Forms of government can be classified by several ways. In terms of the structure of power, there are monarchies (including constitutional monarchies) and republics (usually presidential, semi-presidential, or parliamentary).

The separation of powers describes the degree of horizontal integration between the legislature, the executive, the judiciary, and other independent institutions.

Source of power[]

The source of power determines the difference between democracies, oligarchies, and autocracies.

In a democracy, political legitimacy is based on popular sovereignty. Forms of democracy include representative democracy, direct democracy, and demarchy. These are separated by the way decisions are made, whether by elected representatives, referendums, or by citizen juries. Democracies can be either republics or constitutional monarchies.

Oligarchy is a power structure where a minority rules. These may be in the form of anocracy, aristocracy, ergatocracy, geniocracy, gerontocracy, kakistocracy, kleptocracy, meritocracy, noocracy, particracy, plutocracy, stratocracy, technocracy, theocracy, or timocracy.

Autocracies are either dictatorships (including military dictatorships) or absolute monarchies.

Vertical integration[]

In terms of level of vertical integration, political systems can be divided into (from least to most integrated) confederations, federations, and unitary states.

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governing status of the component states, as well as the division of power between them and the central government, is typically constitutionally entrenched and may not be altered by a unilateral decision of either party, the states or the federal political body. Federations were formed first in Switzerland, then in the United States in 1776, in Canada in 1867 and in Germany in 1871 and in 1901, Australia. Compared to a federation, a confederation has less centralized power.

State[]

All the above forms of government are variations of the same basic polity, the sovereign state. The state has been defined by Max Weber as a political entity that has monopoly on violence within its territory, while the Montevideo Convention holds that states need to have a defined territory; a permanent population; a government; and a capacity to enter into international relations.

A stateless society is a society that is not governed by a state.[54] In stateless societies, there is little concentration of authority; most positions of authority that do exist are very limited in power and are generally not permanently held positions; and social bodies that resolve disputes through predefined rules tend to be small.[55] Stateless societies are highly variable in economic organization and cultural practices.[56]

While stateless societies were the norm in human prehistory, few stateless societies exist today; almost the entire global population resides within the jurisdiction of a sovereign state. In some regions nominal state authorities may be very weak and wield little or no actual power. Over the course of history most stateless peoples have been integrated into the state-based societies around them.[57]

Some political philosophies consider the state undesirable, and thus consider the formation of a stateless society a goal to be achieved. A central tenet of anarchism is the advocacy of society without states.[54][58] The type of society sought for varies significantly between anarchist schools of thought, ranging from extreme individualism to complete collectivism.[59] In Marxism, Marx's theory of the state considers that in a post-capitalist society the state, an undesirable institution, would be unnecessary and wither away.[60] A related concept is that of stateless communism, a phrase sometimes used to describe Marx's anticipated post-capitalist society.

Constitutions[]

Constitutions are written documents that specify and limit the powers of the different branches of government. Although a constitution is a written document, there is also an unwritten constitution. The unwritten constitution is continually being written by the legislative and judiciary branch of government; this is just one of those cases in which the nature of the circumstances determines the form of government that is most appropriate.[61] England did set the fashion of written constitutions during the Civil War but after the Restoration abandoned them to be taken up later by the American Colonies after their emancipation and then France after the Revolution and the rest of Europe including the European colonies.

Constitutions often set out separation of powers, dividing the government into the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary (together referred to as the trias politica), in order to achieve checks and balances within the state. Additional independent branches may also be created, including civil service commissions, election commissions, and supreme audit institutions.

Political culture[]

Political culture describes how culture impacts politics. Every political system is embedded in a particular political culture.[62] Lucian Pye's definition is that "Political culture is the set of attitudes, beliefs, and sentiments, which give order and meaning to a political process and which provide the underlying assumptions and rules that govern behavior in the political system".[62]

Trust is a major factor in political culture, as its level determines the capacity of the state to function.[63] Postmaterialism is the degree to which a political culture is concerned with issues which are not of immediate physical or material concern, such as human rights and environmentalism.[62] Religion has also an impact on political culture.[63]

Political dysfunction[]

Political corruption[]

Political corruption is the use of powers for illegitimate private gain, conducted by government officials or their network contacts. Forms of political corruption include bribery, cronyism, nepotism, and political patronage. Forms of political patronage, in turn, includes clientelism, earmarking, pork barreling, slush funds, and spoils systems; as well as political machines, which is a political system that operates for corrupt ends.

When corruption is embedded in political culture, this may be referred to as patrimonialism or neopatrimonialism. A form of government that is built on corruption is called a kleptocracy ('rule of thieves').

Political conflict[]

Political conflict entails the use of political violence to achieve political ends. As noted by Carl von Clausewitz, "War is a mere continuation of politics by other means."[64] Beyond just inter-state warfare, this may include civil war; wars of national liberation; or asymmetric warfare, such as guerrilla war or terrorism. When a political system is overthrown, the event is called a revolution: it is a political revolution if it does not go further; or a social revolution if the social system is also radically altered. However, these may also be nonviolent revolutions.

Levels of politics[]

Macropolitics[]

Macropolitics can either describe political issues that affect an entire political system (e.g. the nation state), or refer to interactions between political systems (e.g. international relations).[65]

Global politics (or world politics) covers all aspects of politics that affect multiple political systems, in practice meaning any political phenomenon crossing national borders. This can include cities, nation-states, multinational corporations, non-governmental organizations, and/or international organizations. An important element is international relations: the relations between nation-states may be peaceful when they are conducted through diplomacy, or they may be violent, which is described as war. States that are able to exert strong international influence are referred to as superpowers, whereas less-powerful ones may be called regional or middle powers. The international system of power is called the world order, which is affected by the balance of power that defines the degree of polarity in the system. Emerging powers are potentially destabilizing to it, especially if they display revanchism or irredentism.

Politics inside the limits of political systems, which in contemporary context correspond to national borders, are referred to as domestic politics. This includes most forms of public policy, such as social policy, economic policy, or law enforcement, which are executed by the state bureaucracy.

Mesopolitics[]

Mesopolitics describes the politics of intermediary structures within a political system, such as national political parties or movements.[65]

A political party is a political organization that typically seeks to attain and maintain political power within government, usually by participating in political campaigns, educational outreach, or protest actions. Parties often espouse an expressed ideology or vision, bolstered by a written platform with specific goals, forming a coalition among disparate interests.[66]

Political parties within a particular political system together form the party system, which can be either multiparty, two-party, dominant-party, or one-party, depending on the level of pluralism. This is affected by characteristics of the political system, including its electoral system. According to Duverger's law, first-past-the-post systems are likely to lead to two-party systems, while proportional representation systems are more likely to create a multiparty system.

Micropolitics[]

Micropolitics describes the actions of individual actors within the political system.[65] This is often described as political participation.[67] Political participation may take many forms, including:

- Activism

- Boycott

- Civil disobedience

- Demonstration

- Petition

- Picketing

- Strike action

- Tax resistance

- Voting (or its opposite, abstentionism)

Political values[]

Democracy[]

| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

|

|

|

Democracy is a system of processing conflicts in which outcomes depend on what participants do, but no single force controls what occurs and its outcomes. The uncertainty of outcomes is inherent in democracy. Democracy makes all forces struggle repeatedly to realize their interests and devolves power from groups of people to sets of rules.[68]

Among modern political theorists, there are three contending conceptions of democracy: aggregative, deliberative, and radical.[69]

Aggregative[]

The theory of aggregative democracy claims that the aim of the democratic processes is to solicit the preferences of citizens, and aggregate them together to determine what social policies the society should adopt. Therefore, proponents of this view hold that democratic participation should primarily focus on voting, where the policy with the most votes gets implemented.

Different variants of aggregative democracy exist. Under minimalism, democracy is a system of government in which citizens have given teams of political leaders the right to rule in periodic elections. According to this minimalist conception, citizens cannot and should not "rule" because, for example, on most issues, most of the time, they have no clear views or their views are not well-founded. Joseph Schumpeter articulated this view most famously in his book Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy.[70] Contemporary proponents of minimalism include William H. Riker, Adam Przeworski, Richard Posner.

According to the theory of direct democracy, on the other hand, citizens should vote directly, not through their representatives, on legislative proposals. Proponents of direct democracy offer varied reasons to support this view. Political activity can be valuable in itself, it socializes and educates citizens, and popular participation can check powerful elites. Most importantly, citizens do not rule themselves unless they directly decide laws and policies.

Governments will tend to produce laws and policies that are close to the views of the median voter—with half to their left and the other half to their right. This is not a desirable outcome as it represents the action of self-interested and somewhat unaccountable political elites competing for votes. Anthony Downs suggests that ideological political parties are necessary to act as a mediating broker between individual and governments. Downs laid out this view in his 1957 book An Economic Theory of Democracy.[71]

Robert A. Dahl argues that the fundamental democratic principle is that, when it comes to binding collective decisions, each person in a political community is entitled to have his/her interests be given equal consideration (not necessarily that all people are equally satisfied by the collective decision). He uses the term polyarchy to refer to societies in which there exists a certain set of institutions and procedures which are perceived as leading to such democracy. First and foremost among these institutions is the regular occurrence of free and open elections which are used to select representatives who then manage all or most of the public policy of the society. However, these polyarchic procedures may not create a full democracy if, for example, poverty prevents political participation.[72] Similarly, Ronald Dworkin argues that "democracy is a substantive, not a merely procedural, ideal."[73]

Deliberative[]

Deliberative democracy is based on the notion that democracy is government by deliberation. Unlike aggregative democracy, deliberative democracy holds that, for a democratic decision to be legitimate, it must be preceded by authentic deliberation, not merely the aggregation of preferences that occurs in voting. Authentic deliberation is deliberation among decision-makers that is free from distortions of unequal political power, such as power a decision-maker obtained through economic wealth or the support of interest groups.[74][75][76] If the decision-makers cannot reach consensus after authentically deliberating on a proposal, then they vote on the proposal using a form of majority rule.

Radical[]

Radical democracy is based on the idea that there are hierarchical and oppressive power relations that exist in society. Democracy's role is to make visible and challenge those relations by allowing for difference, dissent and antagonisms in decision-making processes.

Equality[]

Equality is a state of affairs in which all people within a specific society or isolated group have the same social status, especially socioeconomic status, including protection of human rights and dignity, and equal access to certain social goods and social services. Furthermore, it may also include health equality, economic equality and other social securities. Social equality requires the absence of legally enforced social class or caste boundaries and the absence of discrimination motivated by an inalienable part of a person's identity. To this end there must be equal justice under law, and equal opportunity regardless of, for example, sex, gender, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, origin, caste or class, income or property, language, religion, convictions, opinions, health or disability.

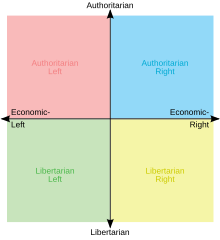

Left–right spectrum[]

A common way of understanding politics is through the left–right political spectrum, which ranges from left-wing politics via centrism to right-wing politics. This classification is comparatively recent and dates from the French Revolution, when those members of the National Assembly who supported the republic, the common people and a secular society sat on the left and supporters of the monarchy, aristocratic privilege and the Church sat on the right.[85]

Today, the left is generally progressivist, seeking social progress in society. The more extreme elements of the left, named the far-left, tend to support revolutionary means for achieving this. This includes ideologies such as Communism and Marxism. The center-left, on the other hand, advocate for more reformist approaches, for example that of social democracy.

In contrast, the right is generally motivated by conservatism, which seeks to conserve what it sees as the important elements of society. The far-right goes beyond this, and often represents a reactionary turn against progress, seeking to undo it. Examples of such ideologies have included Fascism and Nazism. The center-right may be less clear-cut and more mixed in this regard, with neoconservatives supporting the spread of democracy, and one-nation conservatives more open to social welfare programs.

According to Norberto Bobbio, one of the major exponents of this distinction, the left believes in attempting to eradicate social inequality—believing it to be unethical or unnatural,[86] while the right regards most social inequality as the result of ineradicable natural inequalities, and sees attempts to enforce social equality as utopian or authoritarian.[87] Some ideologies, notably Christian Democracy, claim to combine left and right-wing politics; according to Geoffrey K. Roberts and Patricia Hogwood, "In terms of ideology, Christian Democracy has incorporated many of the views held by liberals, conservatives and socialists within a wider framework of moral and Christian principles."[88] Movements which claim or formerly claimed to be above the left-right divide include Fascist Terza Posizione economic politics in Italy and Peronism in Argentina.[89][90]

Freedom[]

Political freedom (also known as political liberty or autonomy) is a central concept in political thought and one of the most important features of democratic societies. Negative liberty has been described as freedom from oppression or coercion and unreasonable external constraints on action, often enacted through civil and political rights, while positive liberty is the absence of disabling conditions for an individual and the fulfillment of enabling conditions, e.g. economic compulsion, in a society. This capability approach to freedom requires economic, social and cultural rights in order to be realized.

Authoritarianism and libertarianism[]

Authoritarianism and libertarianism disagree the amount of individual freedom each person possesses in that society relative to the state. One author describes authoritarian political systems as those where "individual rights and goals are subjugated to group goals, expectations and conformities,"[91] while libertarians generally oppose the state and hold the individual as sovereign. In their purest form, libertarians are anarchists,[92] who argue for the total abolition of the state, of political parties and of other political entities, while the purest authoritarians are, by definition, totalitarians who support state control over all aspects of society.[93]

For instance, classical liberalism (also known as laissez-faire liberalism)[94] is a doctrine stressing individual freedom and limited government. This includes the importance of human rationality, individual property rights, free markets, natural rights, the protection of civil liberties, constitutional limitation of government, and individual freedom from restraint as exemplified in the writings of John Locke, Adam Smith, David Hume, David Ricardo, Voltaire, Montesquieu and others. According to the libertarian Institute for Humane Studies, "the libertarian, or 'classical liberal,' perspective is that individual well-being, prosperity, and social harmony are fostered by 'as much liberty as possible' and 'as little government as necessary.'"[95] For anarchist political philosopher L. Susan Brown (1993), "liberalism and anarchism are two political philosophies that are fundamentally concerned with individual freedom yet differ from one another in very distinct ways. Anarchism shares with liberalism a radical commitment to individual freedom while rejecting liberalism's competitive property relations."[96]

See also[]

- Political history of the world

- Index of law articles

- Index of politics articles – alphabetical list of political subjects

- List of politics awards

- List of years in politics

- Outline of law

- Outline of political science – structured list of political topics, arranged by subject area

- Political lists – lists of political topics

- Politics of present-day states

- List of political ideologies

References[]

Notes[]

Citations[]

- ^ Leftwich 2015, p. 68.

- ^ Hague & Harrop 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Johnston & Woodburn 1903, p. 233.

- ^ Hammarlund 1985, p. 8.

- ^ Brady 2017, p. 47.

- ^ Hawkesworth & Kogan 2013, p. 299.

- ^ Taylor 2012, p. 130.

- ^ Blanton & Kegley 2016, p. 199.

- ^ Kabashima & White III 1986.

- ^ Buhler, C. F., ed. 1961 [1941]. The Dictes and Sayings of the Philosophers. London: Early English Text Society, Original Series No. 211.

- ^ Lewis & Short 1879, online.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "A Greek-English Lexicon". Perseus Digital Library. Tufts Library. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ Lasswell 1963.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Easton 1981.

- ^ Lenin 1965.

- ^ Crick 1972.

- ^ Leftwich 2004.

- ^ Leftwich 2004, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Leftwich 2004, p. 23.

- ^ Leftwich 2004, p. 119.

- ^ Dahl 2003, pp. 1–11.

- ^ Morlino 2017, p. 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Atkinson 2013, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Leftwich 2004, p. 73.

- ^ Leftwich 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Morlino 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Schattschneider, Elmer Eric (1960). The semisovereign people : a realist's view of democracy in America. Dryden P. p. 2. ISBN 0-03-013366-1. OCLC 859587564.

- ^ Mouffe, Chantal (1999). The Challenge of Carl Schmitt. Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-244-7.

- ^ van der Eijk 2018, pp. 11, 29.

- ^ de Waal, Frans (2007). Chimpanzee politics power and sex among apes. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8656-0. OCLC 493546705.

- ^ Fukuyama, Francis (2012). The origins of political order : from prehuman times to the French Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-374-53322-9. OCLC 1082411117.

- ^ Spencer, Charles S.; Redmond, Elsa M. (15 September 2004). "Primary State Formation in Mesoamerica". Annual Review of Anthropology. 33 (1): 173–199. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143823. ISSN 0084-6570.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Carneiro 1970, pp. 733–738.

- ^ Origins of the state : the anthropology of political evolution. Philadelphia : Institute for the Study of Human Issues. 1978. p. 30 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Daniel 2003, p. xiii.

- ^ Daniel 2003, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Nelson & Nelson 2006, p. 17.

- ^ Osiander 2001, p. 251.

- ^ Gross 1948, pp. 20–41.

- ^ Jackson, R. H. 2005. "The Evolution of World Society" in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, edited by P. Owens. J. Baylis and S. Smith. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 1-56584-727-X.[verification needed]

- ^ Kissinger 2014.

- ^ Krasner, Stephen D. (2010). "The durability of organized hypocrisy". In Kalmo, Hent; Skinner, Quentin (eds.). Sovereignty in Fragments: The Past, Present and Future of a Contested Concept. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "From Westphalia, with love – Indian Express". archive.indianexpress.com. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ ^ Eric Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism since 1780 : programme, myth, reality (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990; ISBN 0-521-43961-2) chapter II "The popular protonationalism", pp.80–81 French edition (Gallimard, 1992). According to Hobsbawm, the main source for this subject is Ferdinand Brunot (ed.), Histoire de la langue française, Paris, 1927–1943, 13 volumes, in particular volume IX. He also refers to Michel de Certeau, Dominique Julia, Judith Revel, Une politique de la langue: la Révolution française et les patois: l'enquête de l'abbé Grégoire, Paris, 1975. For the problem of the transformation of a minority official language into a widespread national language during and after the French Revolution, see Renée Balibar, L'Institution du français: essai sur le co-linguisme des Carolingiens à la République, Paris, 1985 (also Le co-linguisme, PUF, Que sais-je?, 1994, but out of print) The Institution of the French language: essay on colinguism from the Carolingian to the Republic. Finally, Hobsbawm refers to Renée Balibar and Dominique Laporte, Le Français national: politique et pratique de la langue nationale sous la Révolution, Paris, 1974.

- ^ Al-Rasheed, Madawi; Kersten, Carool; Shterin, Marat (11 December 2012). Demystifying the Caliphate: Historical Memory and Contemporary Contexts. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-932795-9.

- ^ Richards, Howard (2004). Understanding the Global Economy. Peace Education Books. ISBN 978-0-9748961-0-6.

- ^ Black, Jeremy.1998. Maps and Politics. pp. 59–98, 100–47.

- ^ Foucault, Michel. [1977–1978] 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France.

- ^ Rizaldy, Aldino, and Wildan Firdaus. 2012. "Direct Georeferencing: A New Standard in Photogrammetry for High Accuracy Mapping." International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 39(B1):5–9. doi:10.5194/isprsarchives-XXXIX-B1-5-2012.

- ^ Bellezza, Giuliano. 2013. "On Borders: From Ancient to Postmodern Times." Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 40-4(W3):1–7. doi:10.5194/isprsarchives-XL-4-W3-1-2013.

- ^ Mikhailova, E. V. 2013. "Appearance and Appliance of the Twin-Cities Concept on the Russian-Chinese Border." Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 40-4(W3):105–10. doi:10.5194/isprsarchives-XL-4-W3-105-2013.

- ^ Pickering, S. 2013. "Borderlines: Maps and the spread of the Westphalian state from Europe to Asia Part One – The European Context." Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 40-4(W3):111–16. doi:10.5194/isprsarchives-XL-4-W3-111-2013.

- ^ Branch 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Craig 2005, p. 14.

- ^ Ellis, Stephen (2001). The Mask of Anarchy: The Destruction of Liberia and the Religious Dimension of an African Civil War. NYU Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8147-2219-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Béteille 2002, pp. 1042–1043.

- ^ Faulks, Keith (2000). Political Sociology: A Critical Introduction. NYU Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8147-2709-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sheehan, Sean (2004). Anarchism. London: Reaktion Books. p. 85.

- ^ Slevin, Carl (2003). "Anarchism". In McLean, Iain & McMillan, Alistair (eds.). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280276-7.

- ^ Engels, Frederick (1880). "Part III: Historical Materialism". Socialism: Utopian and Scientific – via Marx/Engels Internet Archive (marxists.org).

State interference in social relations becomes, in one domain after another, superfluous, and then dies out of itself; the government of persons is replaced by the administration of things, and by the conduct of processes of production. The State is not "abolished". It dies out...Socialized production upon a predetermined plan becomes henceforth possible. The development of production makes the existence of different classes of society thenceforth an anachronism. In proportion as anarchy in social production vanishes, the political authority of the State dies out. Man, at last the master of his own form of social organization, becomes at the same time the lord over Nature, his own master—free.

- ^ "Britain's unwritten constitution". The British Library. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Morlino, Berg-Schlosser & Badie 2017, pp. 64–74.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hague 2017, pp. 200–214.

- ^ Von Clausewitz, Carl (1 October 2010). On War – Volume I – Chapter II. The Floating Press. ISBN 978-1-77541-926-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Morlino, Berg-Schlosser & Badie 2017, p. 20.

- ^ Pettitt 2014, p. 60.

- ^ Morlino, Berg-Schlosser & Badie 2017, p. 161.

- ^ Przeworski, Adam (1991). Democracy and the Market. Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–14.

- ^ Springer, Simon (2011). "Public Space as Emancipation: Meditations on Anarchism, Radical Democracy, Neoliberalism and Violence". Antipode. 43 (2): 525–62. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00827.x.

- ^ Joseph Schumpeter, (1950). Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-133008-6.

- ^ Downs 1957.

- ^ Dahl 1989.

- ^ Dworkin, Ronald. 2006. Is Democracy Possible Here? Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13872-5. p. 134.

- ^ Gutmann, Amy, and Dennis Thompson. 2002. Why Deliberative Democracy? Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12019-5

- ^ Cohen, Joshua. 1997. "Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy." In Essays on Reason and Politics: Deliberative Democracy, edited by J. Bohman and W. Rehg. Cambridge: The MIT Press. pp. 72–73.

- ^ Ethan J. 2006. "Can Direct Democracy Be Made Deliberative?" Buffalo Law Review 54.

- ^ Heywood 2017, pp. 14–17.

- ^ Love 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Petrik 2010, p. 4.

- ^ Sznajd-Weron & Sznajd 2005, pp. 593–604.

- ^ Forman, F. N.; Baldwin, N. D. J. (1999). Mastering British Politics. London: Macmillan Education UK. pp. 8 f. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-15045-8. ISBN 978-0-333-76548-7.

- ^ Fenna, Alan; Robbins, Jane; Summers, John (2013). Government Politics in Australia. Robbins, Jane., Summers, John. (10th ed.). Melbourne: Pearson Higher Education AU. pp. 126 f. ISBN 978-1-4860-0138-5. OCLC 1021804010.

- ^ Jones & Kavanagh 2003, p. 259.

- ^ Körösényi, András (1999). Government and Politics in Hungary. Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press. p. 54. ISBN 963-9116-76-9. OCLC 51478878.

- ^ Knapp, Andrew; Wright, Vincent (2006). The Government and Politics of France. London: Routledge.

- ^ Gelderloos, Peter (2010). Anarchy Works.

- ^ Bobbio 1997.

- ^ Roberts & Hogwood 1997.

- ^ Tore 2014.

- ^ "bale p.40" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Kemmelmeier et al. 2003, pp. 304–322.

- ^ "An Anarchist FAQ: 150 years of Libertarian". Anarchists Writers. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ "totalitarian". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 25 September 2018. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018.

- ^ Adams, Ian. 2001. Political Ideology Today. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 20.

- ^ IHS. 2019. "What Is Libertarian?." Institute for Humane Studies. George Mason University. Archived 24 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Brown, L. Susan. 1993. The Politics of Individualism: Liberalism, Liberal Feminism, and Anarchism. Black Rose Books.

Bibliography[]

- Atkinson, Sam (2013). The politics book. DK. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-1-4093-6445-0. OCLC 868135821.

- Béteille, André (2002). "Inequality and Equality". In Ingold, Tim (ed.). Companion Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1042–1043. ISBN 978-0-415-28604-6 – via Google Books.

- Blanton, Shannon L.; Kegley, Charles W. (2016). World Politics: Trend and Transformation, 2016–2017. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-305-50487-5. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- Bobbio, Norberto (1997). Left and Right: The Significance of a Political Distinction. Translated by Cameron, A. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06246-4.

- Brady, Linda P. (2017). The Politics of Negotiation: America's Dealings with Allies, Adversaries, and Friends. University of North Carolina Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-4696-3960-4. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Branch, Jordan (2011). "Mapping the Sovereign State: Technology, Authority, and Systemic Change". International Organization. 65 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1017/S0020818310000299. ISSN 0020-8183. JSTOR 23016102. S2CID 144712038. Retrieved 7 February 2021. Lay summary – Wilson Quarterly.

- Branch, Jordan Nathaniel (2011). Mapping the Sovereign State: Cartographic Technology, Political Authority, and Systemic Change (PhD thesis). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- Carneiro, Robert L. (21 August 1970). "A Theory of the Origin of the State: Traditional theories of state origins are considered and rejected in favor of a new ecological hypothesis". Science. 169 (3947): 733–738. doi:10.1126/science.169.3947.733. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17820299. S2CID 11536431.

- Craig, Edward, ed. (2005). "Anarchism". The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-134-34409-3.

Anarchism is the view that a society without the state, or government, is both possible and desirable.

- Crick, Bernard (1972). In defence of politics. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-12064-3. OCLC 575753.

- Dahl, Robert A. (1989). Democracy and its critics. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04938-2.

- Dahl, Robert A. (2003). Modern political analysis. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-049702-9. OCLC 49611149.

- Daniel, Glyn (2003) [1968]. The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of their Origins. New York: Phoenix Press. xiii. ISBN 1-84212-500-1.

- Downs, Anthony (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper Collins College. ISBN 978-0-06-041750-5.

- Easton, David (1981). The political system: an inquiry into the state of political science (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-18017-5. OCLC 781301164.

- Gross, Leo (January 1948). "The Peace of Westphalia" (PDF). The American Journal of International Law. 42 (1): 20–41. doi:10.2307/2193560. JSTOR 2193560.

- Hague, Rod; Harrop, Martin (2013). Comparative Government and Politics: An Introduction. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 978-1-137-31786-5. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Hague, Rod (14 October 2017). Political Science: A Comparative Introduction. pp. 200–214. ISBN 978-1-137-60123-0. OCLC 970345358.

- Hammarlund, Bo (1985). Politik utan partier: studier i Sveriges politiska liv 1726–1727. Almqvist & Wiksell International. ISBN 978-91-22-00780-7. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Hawkesworth, Mary; Kogan, Maurice (2013). Encyclopedia of Government and Politics: 2-volume Set. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-91332-7. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Heywood, Andrew (2017). Political Ideologies: An Introduction (6th ed.). Basingstoke: Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 978-1-137-60604-4. OCLC 988218349.

- Johnston, Alexander; Woodburn, James Albert (1903) [1903]. American Orations: V. The Anti-Slavery Struggle. G. P. Putnam and Sons. – via Internet Archive.

- Jones, Bill; Kavanagh, Dennis (2003). British Politics Today. Kavanagh, Dennis. (7th ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6509-5. OCLC 52876930.

- Kabashima, Ikuo; White III, Lynn T., eds. (1986). Political System and Change: A World Politics Reader. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-61037-5. JSTOR j.ctt7ztn7s.

- Kemmelmeier, Markus; et al. (2003). "Individualism, Collectivism, and Authoritarianism in Seven Societies". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 34 (3): 304–322. doi:10.1177/0022022103034003005. S2CID 32361036.

- Kissinger, Henry (2014). World Order. ISBN 978-0-698-16572-4.

- Lasswell, Harold D. (1963) [1958]. Politics: who gets what, when how. : With postscript. World. OCLC 61585455.

- Leftwich, Adrian (2004). What is politics? : the activity and its study. Polity. ISBN 0-7456-3055-3. OCLC 1044115261.

- Leftwich, Adrian (2015). What is politics? : the activity and its study. Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-9852-6. OCLC 911200604.

- Lenin, Vladimir I. (1965). Collected works. September 1903 – December 1904. OCLC 929381958.

- Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879). "pŏlītĭcus". A Latin Dictionary. Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2016 – via Perseus Digital Library.

- Love, Nancy Sue (2006). Understanding Dogmas and Dreams (Second ed.). Washington, District of Columbia: CQ Press. ISBN 978-1-4833-7111-5. OCLC 893684473.

- Morlino, Leonardo (2017). Political science. Sage Publications Inc. ISBN 978-1-4129-6213-1. OCLC 951226897.

- Morlino, Leonardo; Berg-Schlosser, Dirk; Badie, Bertrand (6 March 2017). Political science : a global perspective. London, England. pp. 64–74. ISBN 978-1-5264-1303-1. OCLC 1124515503.

- Nelson, B.; Nelson, Brian R. (16 March 2006). The Making of the Modern State: A Theoretical Evolution. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-7189-0.

- Osiander, Andreas (2001). "Sovereignty, International Relations, and the Westphalian Myth". International Organization. 55 (2): 251–287. doi:10.1162/00208180151140577. S2CID 145407931.

- Petrik, Andreas (3 December 2010). "Core Concept 'Political Compass'. How Kitschelt's Model of Liberal, Socialist, Libertarian and Conservative Orientations Can Fill the Ideology Gap in Civic Education". JSSE – Journal of Social Science Education: 4. doi:10.4119/jsse-541. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019.

- Pettitt, Robin T. (2014). Contemporary Party Politics. London: Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 978-1-137-41264-5. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019 – via Google Books.

- Roberts and Hogwood, European Politics Today, Manchester University Press, 1997.

- Sznajd-Weron, Katarzyna; Sznajd, Józef (June 2005). "Who is left, who is right?". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications. 351 (2–4): 593–604. Bibcode:2005PhyA..351..593S. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2004.12.038.

- Taylor, Steven L. (2012). 30-Second Politics: The 50 most thought-provoking ideas in politics, each explained in half a minute. Icon Books Limited. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-84831-427-6. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Tore, Bjorgo (2014). Terror from the Extreme Right. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-20930-8. OCLC 871861016.

- van der Eijk, Cees (2018). "What Is Politics?". The Essence of Politics. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 9–24. doi:10.2307/j.ctvf3w22g.4. JSTOR j.ctvf3w22g.

Further reading[]

- Adcock, Robert. 2014. Liberalism and the Emergence of American Political Science: A Transatlantic Tale. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Adcock, Robert, Mark Bevir, and Shannon Stimson (eds.). 2007. Modern Political Science: Anglo-American Exchanges Since 1870. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Almond, Gabriel A. 1996. “Political Science: The History of the Discipline,” pp. 50–96, in Robert E. Goodin and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (eds.), The New Handbook of Political Science. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Connolly, William (1981). Appearance and Reality in Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- James, Raul; Soguk, Nevzat (2014). Globalization and Politics, Vol. 1: Global Political and Legal Governance. London: Sage Publications. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Mount, Ferdinand, "Ruthless and Truthless" (review of Peter Oborne, The Assault on Truth: Boris Johnson, Donald Trump and the Emergence of a New Moral Barbarism, Simon and Schuster, February 2021, ISBN 978 1 3985 0100 3, 192 pp.; and Colin Kidd and Jacqueline Rose, eds., Political Advice: Past, Present and Future, I.B. Tauris, February 2021, ISBN 978 1 83860 004 4, 240 pp.), London Review of Books, vol. 43, no. 9 (6 May 2021), pp. 3, 5–8.

- Munck, Gerardo L., and Richard Snyder (eds.). Passion, Craft, and Method in Comparative Politics. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

- Ross, Dorothy. 1991. The Origins of American Social Science. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ryan, Alan (2012). On Politics: A History of Political Thought from Herodotus to the Present. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9364-6.

- Politics

- Main topic articles