Progressivism

| Part of a series on |

| Progressivism |

|---|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Party politics |

|---|

|

|

Progressivism is a political philosophy in support of social reform.[1] Based on the idea of progress in which advancements in science, technology, economic development and social organization are vital to the improvement of the human condition, progressivism became highly significant during the Age of Enlightenment in Europe, out of the belief that Europe was demonstrating that societies could progress in civility from uncivilized conditions to civilization through strengthening the basis of empirical knowledge as the foundation of society.[2] Figures of the Enlightenment believed that progress had universal application to all societies and that these ideas would spread across the world from Europe.[2]

The contemporary common political conception of progressivism emerged from the vast social changes brought about by industrialization in the Western world in the late 19th century. Progressives take the view that progress is being stifled by vast economic inequality between the rich and the poor; minimally regulated laissez-faire capitalism with monopolistic corporations; and the intense and often violent conflict between those perceived to be privileged and unprivileged, arguing that measures were needed to address these problems.[3]

The meaning of progressivism has varied over time and differs depending on perspective. Early-20th century progressivism was tied to eugenics and the temperance movement, both of which were promoted in the name of public health and as initiatives toward that goal.[4][5][6][7][8] Contemporary progressives promote public policies that they believe will lead to positive social change. In the 21st century, a movement that identifies as progressive is "a social or political movement that aims to represent the interests of ordinary people through political change and the support of government actions".[9]

History[]

From the Enlightenment to the Industrial Revolution[]

Immanuel Kant identified progress as being a movement away from barbarism towards civilization. 18th-century philosopher and political scientist Marquis de Condorcet predicted that political progress would involve the disappearance of slavery, the rise of literacy, the lessening of sex inequality, prison reforms which at the time were harsh and the decline of poverty.[10]

Modernity or modernization was a key form of the idea of progress as promoted by classical liberals in the 19th and 20th centuries who called for the rapid modernization of the economy and society to remove the traditional hindrances to free markets and free movements of people.[11]

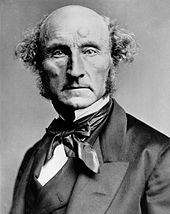

In the late 19th century, a political view rose in popularity in the Western world that progress was being stifled by vast economic inequality between the rich and the poor, minimally regulated laissez-faire capitalism with out-of-control monopolistic corporations, intense and often violent conflict between capitalists and workers, with a need for measures to address these problems.[12] Progressivism has influenced various political movements. Social liberalism was influenced by British liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill's conception of people being "progressive beings".[13] British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli developed progressive conservatism under one-nation Toryism.[14][15]

In France, the space between social revolution and the socially-conservative laissez-faire centre-right was filled with the emergence of radicalism which thought that social progress required anti-clericalism, humanism and republicanism. Especially anti-clericalism was the dominant influence on the centre-left in many French- and Romance-speaking countries until the mid 20th-century. In Imperial Germany, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck enacted various progressive social welfare measures out of paternalistic conservative motivations to distance workers from the socialist movement of the time and as humane ways to assist in maintaining the Industrial Revolution.[16]

In 1891, the Roman Catholic Church encyclical Rerum novarum issued by Pope Leo XIII condemned the exploitation of labour and urged support for labour unions and government regulation of businesses in the interests of social justice while upholding the right to property and criticizing socialism.[17] A Protestant progressive outlook called the Social Gospel emerged in North America that focused on challenging economic exploitation and poverty and by the mid-1890s was common in many Protestant theological seminaries in the United States.[18]

Contemporary mainstream political conception to the philosophy[]

In the United States, progressivism began as an intellectual rebellion against the political philosophy of Constitutionalism[19] as expressed by John Locke and the founders of the American Republic, whereby the authority of government depends on observing limitations on its just powers.[20] What began as a social movement in the 1890s, grew into a popular political movement referred to as the Progressive era; in the 1912 United States presidential election, all three U.S. presidential candidates claimed to be progressives. While the term progressivism represent a range of diverse political pressure groups, not always united, progressives rejected social Darwinism, believing that the problems society faced such as class warfare, greed, poverty, racism and violence could best be addressed by providing good education, a safe environment and an efficient workplace. Progressives lived mainly in the cities, were college educated and believed that government could be a tool for change.[21] President Theodore Roosevelt of the Republican Party and later the Progressive Party declared that he "always believed that wise progressivism and wise conservatism go hand in hand".[22]

President Woodrow Wilson was also a member of the American progressive movement within the Democratic Party. Progressive stances have evolved over time. Imperialism was a controversial issue within progressivism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in the United States, where some progressives supported American imperialism while others opposed it.[23] In response to World War I, President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points established the concept of national self-determination and criticized imperialist competition and colonial injustices. These views were supported by anti-imperialists in areas of the world that were resisting imperial rule.[24]

During the period of acceptance of economic Keynesianism (1930s–1970s), there was widespread acceptance in many nations of a large role for state intervention in the economy. With the rise of neoliberalism and challenges to state interventionist policies in the 1970s and 1980s, centre-left progressive movements responded by adopting the Third Way that emphasized a major role for the market economy.[25] There have been social democrats who have called for the social-democratic movement to move past Third Way.[26] Prominent progressive conservative elements in the British Conservative Party have criticized neoliberalism.[27]

In the 21st century, progressives continue to favour public policy that reduces or ameliorates the harmful effects of economic inequality as well as systemic discrimination such as institutional racism; to advocate for environmentally conscious policies as well as for social safety nets and workers' rights; and to oppose the negative externalities inflicted on the environment and society by monopolies or corporate influence on the democratic process. The unifying theme is to call attention to the negative impacts of current institutions or ways of doing things and to advocate for social progress, i.e. for positive change as defined by any of several standards such as expansion of democracy, increased egalitarianism in the form of economic and social equality as well as improved well being of a population. Proponents of social democracy have identified themselves as promoting the progressive cause.[28]

See also[]

- Australian Progressives

- Affirmative action

- Centre-left politics

- Democracy

- Democratic socialism

- Green politics

- Left-wing politics

- Liberalism

- Jim Anderton's Progressive Party

- Managerial state

- Modern liberalism in the United States

- Progressive conservatism

- Progressive Era

- Progressive Party of Canada

- Progressive Party (United States, 1912)

- Progressive Party (United States, 1924–34)

- Progressive Party (United States, 1948)

- Progressive tax

- Progressivism in the United States

- Radical centrism

- Radicalism (historical)

- Secularism

- Social Justice

- Secular liberalism

- Social democracy

- Socialism

- Transhumanism

- Transhumanist politics

- Techno-progressivism

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ "Progressivism in English". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harold Mah. Enlightenment Phantasies: Cultural Identity in France and Germany, 1750–1914. Cornell University. (2003). p. 157.

- ^ Nugent, Walter (2010). Progressivism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780195311068.

- ^ "Prohibition: A Case Study of Progressive Reform". Library of Congress. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas (2005). "Retrospectives: Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 19 (4): 207–224. doi:10.1257/089533005775196642. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Roll-Hansen, Nils (1989). "Geneticists and the Eugenics Movement in Scandinavia". The British Journal for the History of Science. 22 (3): 335–346. doi:10.1017/S0007087400026194. JSTOR 4026900. PMID 11621984.

- ^ Freeden, Michael (2005). Liberal Languages: Ideological Imaginations and Twentieth-Century Progressive Thought. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 144–165. ISBN 978-0691116778.

- ^ James H. Timberlake, Prohibition and the Progressive Movement, 1900–1920 (1970)

- ^ "Progressivism". The Cambridge English Dictionary. 24 June 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ Nisbet, Robert (1980). History of the Idea of Progress. New York: Basic Books. ch 5

- ^ Joyce Appleby; Lynn Hunt & Margaret Jacob (1995). Telling the Truth about History. p. 78. ISBN 9780393078916.

- ^ Nugent, Walter (2010). Progressivism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780195311068.

- ^ Alan Ryan. The Making of Modern Liberalism. p. 25.

- ^ Patrick Dunleavy, Paul Joseph Kelly, Michael Moran. British Political Science: Fifty Years of Political Studies. Oxford, England, UK; Malden, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell, 2000. pp. 107–08.

- ^ Robert Blake. Disraeli. Second Edition. London, England, UK: Eyre & Spottiswoode (Publishers) Ltd, 1967. p. 524.

- ^ Union Contributions to Labor Welfare Policy and Practice: Past, Present, and Future. Routledge, 16, 2013. p. 172.

- ^ Faith Jaycox. The Progressive Era. New York, New York: Infobase Publishing, 2005. p. 85.

- ^ Charles Howard Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel in American Protestantism, 1865–1915 (1940).

- ^ Waluchow, Wil (17 August 2018). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Watson, Bradley (2020). Progressivism : the strange history of a radical idea. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0268106973.

- ^ "The Progressive Era (1890–1920)". The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project. Archived 20 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 31 September 2014.

- ^ Jonathan Lurie. William Howard Taft: The Travails of a Progressive Conservative. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012. p. 196.

- ^ Nugent, Walter (2010). Progressivism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780195311068.

- ^ Reconsidering Woodrow Wilson: Progressivism, Internationalism, War, and Peace. p. 309.

- ^ Jane Lewis, Rebecca Surender. Welfare State Change: Towards a Third Way?. Oxford University Press, 2004. pp. 3–4, 16.

- ^ After the Third Way: The Future of Social Democracy in Europe. I. B. Taurus, 2012. p. 47.

- ^ Hugh Bochel. The Conservative Party and Social Policy. The Policy Press, 2011. p. 108.

- ^ Henning Meyer, Jonathan Rutherford. The Future of European Social Democracy: Building the Good Society. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. p. 108.

Sources[]

- Tindall, George and Shi, David E. America: A Narrative History. W W Norton & Co Inc; Full Sixth edition, 2003. ISBN 0-393-92426-2.

- Lakoff, George. Don't Think of an Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-931498-71-7.

- Kelleher, William J. Progressive Logic: Framing A Unified Field Theory of Values For Progressives. The Empathic Science Institute, 2005. ISBN 0-9773717-1-9.

- Kloppenberg, James T.. Uncertain Victory: Social Democracy and Progressivism in European and American Thought, 1870–1920. Oxford University Press, US, 1988. ISBN 0-19-505304-4.

- Link, Arthur S. and McCormick, Richard L.. Progressivism (American History Series). Harlan Davidson, 1983. ISBN 0-88295-814-3.

- McGerr, Michael. A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870–1920. 2003.

- Schutz, Aaron. Social Class, Social Action, and Education: The Failure of Progressive Democracy. Palgrave, Macmillan, 2010. ISBN 978-0-230-10591-1.

- Tröhler, Daniel. Progressivism. In book: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford University Press, 2017.

External links[]

- Progressivism — entry at the Encyclopædia Britannica

Media related to Progressivism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Progressivism at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Progressivism at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Progressivism at Wikiquote

- Progressivism

- Critical thinking

- Democratic socialism

- Justice

- Left-wing politics

- Liberalism

- Political ideologies

- Political movements

- Secularism

- Secular humanism

- Social change

- Social democracy

- Social justice

- Social liberalism

- Social movements

- Sociocultural evolution theory