Cross

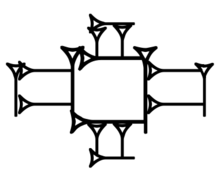

A cross is a geometrical figure consisting of two intersecting lines or bars, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of the Latin letter X, is also termed a saltire in heraldic terminology.

Throughout centuries the cross in its various shapes and forms was a symbol of various beliefs. In pre-Christian times it was a pagan religious symbol throughout Europe and western Asia. In ancient times, the effigy of a man hanging on a cross was set up in the fields to protect the crops. The cross was even considered a male symbol of the phallic Tree of Life; thus it often appeared in conjunction with the female-genital circle or oval, to signify the sacred marriage, as in Egyptian amulet Nefer[1] with male cross and female orb, considered as an amulet of blessedness, a charm of sexual harmony.[2]

Name[]

The word cross is recorded in 11th-century Old English as cros, exclusively for the instrument of Christ's crucifixion, replacing the native Old English word rood. The word's history is complicated; it appears to have entered English from Old Irish, possibly via Old Norse, ultimately from the Latin crux (or its accusative crucem and its genitive crucis), "stake, cross". The English verb to cross arises from the noun c. 1200, first in the sense "to make the sign of the cross"; the generic meaning "to intersect" develops in the 15th century. The Latin word was, however, influenced by popular etymology by a native Germanic word reconstructed as *krukjo (English crook, Old English crycce, Old Norse krokr, Old High German krucka). This word, by conflation with Latin crux, gave rise to Old French crocier (modern French crosse), the term for a shepherd's crook, adopted in English as crosier.

Latin crux referred to the gibbet where criminals were executed, a stake or pole, with or without transom, on which the condemned were impaled or hanged, but more particularly a cross or the pole of a carriage.[3] The derived verb cruciāre means "to put to death on the cross" or, more frequently, "to put to the rack, to torture, torment", especially in reference to mental troubles.[4] In the Roman world, furca replaced crux as the name of some cross-like instruments for lethal and temporary punishment,[5][6] ranging from a forked cross to a gibbet or gallows.[7]

The field of etymology is of no help in any effort to trace a supposed original meaning of crux.[8] A crux can be of various shapes: from a single beam used for impaling or suspending (crux simplex) to the various composite kinds of cross (crux compacta) made from more beams than one. The latter shapes include not only the traditional †-shaped cross (the crux immissa), but also the T-shaped cross (the crux commissa or tau cross), which the descriptions in antiquity of the execution cross indicate as the normal form in use at that time, and the X-shaped cross (the crux decussata or saltire).

The Greek equivalent of Latin crux "stake, gibbet" is stauros, found in texts of four centuries or more before the gospels and always in the plural number to indicate a stake or pole. From the first century BC, it is used to indicate an instrument used in executions. The Greek word is used in descriptions in antiquity of the execution cross, which indicate that its normal shape was similar to the Greek letter tau (Τ).[9][10][11][12]

History[]

Pre-Christian[]

Due to the simplicity of the design (two intersecting lines), cross-shaped incisions make their appearance from deep prehistory; as petroglyphs in European cult caves, dating back to the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic, and throughout prehistory to the Iron Age.[13] Also of prehistoric age are numerous variants of the simple cross mark, including the crux gammata with curving or angular lines, and the Egyptian crux ansata with a loop.

Speculation has associated the cross symbol – even in the prehistoric period – with astronomical or cosmological symbology involving "four elements" (Chevalier, 1997) or the cardinal points, or the unity of a vertical axis mundi or celestial pole with the horizontal world (Koch, 1955). Speculation of this kind became especially popular in the mid- to late-19th century in the context of comparative mythology seeking to tie Christian mythology to ancient cosmological myths. Influential works in this vein included G. de Mortillet (1866),[14] L. Müller (1865),[15] W. W. Blake (1888),[16] Ansault (1891),[17] etc.