Crusader invasions of Egypt

| Crusader invasion of Egypt | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crusades | ||||||

Crusader invasions of Egypt | ||||||

| ||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||

|

|

| Zengid Emirate | ||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||

|

|

Al-Adid Shawar Dirgham |

Nur ad-Din Shirkuh Saladin | ||||

The Crusader invasions of Egypt (1163–1169) were a series of campaigns undertaken by the Kingdom of Jerusalem to strengthen its position in the Levant by taking advantage of the weakness of Fatimid Egypt.

The war began as part of a succession crisis in the Fatimid Caliphate, which began to crumble under the pressure of Muslim Syria ruled by the Zengid dynasty and the Christian Crusader states. While one side called for help from the emir of Syria, Nur ad-Din Zangi, the other called for Crusader assistance. As the war progressed, however, it became a war of conquest. A number of Syrian campaigns into Egypt were stopped short of total victory by the aggressive campaigning of Amalric I of Jerusalem. Even so, the Crusaders generally speaking did not have things go their way, despite several sackings. A combined Byzantine-Crusader siege of Damietta failed in 1169, the same year that Saladin took power in Egypt as vizier. In 1171, Saladin became sultan of Egypt and the crusaders thereafter turned their attention to the defence of their kingdom, which, despite being surrounded by Syria and Egypt, held for another 16 years. Later crusades tried to support the Kingdom of Jerusalem by targeting the danger that was Egypt, but to no avail.

Background[]

Following the capture of Jerusalem by the forces of the First Crusade, the Fatimids of Egypt launched regular raids into Palestine against the Crusaders, while Zengi of Syria launched a series of successful attacks against the County of Edessa and Principality of Antioch. The Second Crusade aimed to reverse the gains of Zengi, ironically with an assault on Damascus, Zengi's most powerful rival. The siege failed and forced the Kingdom to turn south for better fortunes.

The Fatimid Caliphate in the 12th century was riddled with internal squabbles. In the 1160s, power lay not in the hands of the Fatimid caliph Al-'Āḍid, but in the hands of the vizier of Egypt, Shawar. The situation in Egypt made it ripe for conquest, either by crusaders or by the forces of Zengi's successor, Nur ad-Din. The first Crusader invasion of Egypt culminated in the siege of Ascalon, resulting in the capture of the city in 1154. This meant that the kingdom was now at war in two fronts, but Egypt now had an enemy supply base close at hand.

Amalric invades and intervention of Nur ad-Din, 1163–1164[]

In 1163, Shawar, the ousted Fatimid vizier, who had fled to Syria called Nur ad-Din for support in reinstating him to his former position as the de facto ruler of Egypt against the new vizier, Dirgham. Dirgham attempted to thwart his rival's plans by opening negotiations with Nur al-Din for an alliance against the Crusaders, but the Syrian ruler's reply was non-committal, and on his way to Egypt, Dirgham's envoy was arrested by the Crusaders, possibly on the instigation of Nur al-Din himself.[1]

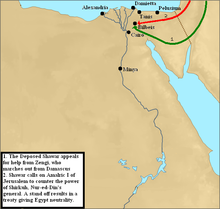

First Crusader invasion, 1163[]

In 1163, King Amalric went to invade Egypt, claiming that the Fatimids had not paid the yearly tribute that had begun during the reign of Baldwin III. The vizier, Dirgham, who had recently overthrown the vizier Shawar, marched out to meet Amalric at Pelusium, but was defeated and forced to retreat to Bilbeis. The Egyptians then opened up the Nile dams and let the river flood, hoping to prevent Amalric from invading any further, thus he returned home.[2] However, Dirgham preferred to negotiate with Amalric, offering him a peace treaty guaranteed by the surrender of hostages, and the payment of an annual tribute.[1] Meanwhile, Nur ad-Din agreed to support Shawar who offered to hand over one third of the annual land tax (kharāj) revenue to Nur al-Din. The latter manoeuvred to attract the Crusaders' attention away from the expeditionary force, as his general Shirkuh accompanied by his nephew, Saladin, crossed the lands of the Kingdom of Jerusalem to enter Egypt.[1]

Dirgham appealed to Amalric for help, but the King of Jerusalem was unable to intervene in time, and in late April 1164, the Syrians surprised and defeated Dirgham's brother Mulham at Bilbeis, opening the way to Cairo.[1] In May 1164, Shawar became vizier of Egypt, and Dirgham was killed, after he had been abandoned by the people and the army. Shawar was, however, a mere figurehead to Nur ad-Din, who had installed Shirkuh as ruler of Egypt. Shawar became unsatisfied with this and called upon the enemy of the Sunni Muslims, King Amalric I of Jerusalem.

Second Crusader invasion, 1164[]

Shawar then argued with Shirkuh, and allied with the Crusader king, Amalric I, who attacked Shirkuh at Bilbeis,[3] in August–October 1164. The siege ended with a stalemate, and both Shirkuh and Amalric agreed to withdraw from Egypt. In the meantime, Nur ad-Din moved his forces against the Crusader state of Antioch and despite being a Byzantine protectorate,[a] defeated and captured Bohemond III of Antioch and Raymond III of Tripoli at the Battle of Harim. Amalric immediately raced north to rescue his vassal. Even so, Shirkuh evacuated Egypt too so it was a victory for Shawar who retained Egypt.

Letter to King of France[]

In 1164, Latin Patriarch of Antioch Aimery of Limoges had sent a letter to King Louis VII of France, in which he described the events in the Crusader States:

[Shirkuh] having gotten possession of Damascus, the latter entered Egypt with a great force of Turks, in order to conquer the country. Accordingly, the king of Egypt, who is also called the sultan of Babylon, distrusting his own valor and that of his men, held a most warlike council to determine how to meet the advancing Turks and how he could obtain the aid of the king of Jerusalem. For he wisely preferred to rule under tribute rather than to be deprived of both life and kingdom.

The former, therefore, as we have said, entered Egypt and favored by certain men of that land, captured and fortified a certain city. In the meantime the sultan made an alliance with the lord king [Amalric] by promising to pay tribute each year and to release all the Christian captives in Egypt, and obtained the aid of the lord king. The latter, before setting out, committed the care of his kingdom and land, until his return, to us and to our new prince, his kinsman Bohemond, son of the former prince Raymond.

Therefore, the great devastator of the Christian people, who rules near us, collected together from all sides the kings and races of the infidels arid offered a peace and truce to our prince and very frequently urged it. His reason was that he wished to traverse our land with greater freedom in order to devastate the kingdom of Jerusalem and to be able to bear aid to his vassal fighting in Egypt. But our prince was unwilling to make peace with him until the return of our lord king.

— [4]

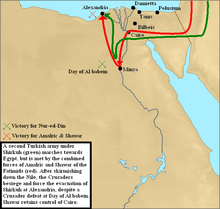

Shirkuh returns and third Crusader invasion, 1166–1167[]

Shawar's rule in Egypt did not last long before Shirkuh returned in 1166 to take back Egypt. Shawar played his crusader card again and this time Amalric believed an open battle would be able to settle the scores. Unlike Shirkuh, Amalric had naval supremacy in the Mediterranean (though to be fair there were few Syrian ports to the Mediterranean under Nur ad-Din) and took a quick coastal route to Egypt, allowing him to link up with his ally Shawar just as Nur ad-Din's deputy Shirkuh arrived in January 1167. Shirkuh who had marched through the Desert of Tih south of Sinai Peninsula, preferring to face a sand storm there rather than alerting the Crusaders,[5] camped at Giza opposite to Cairo. Amalric troops had tried to intercept Shirkuh's army, but failed to surprise the convoy. While in Bilbeis, Amalric had an agreement with Shawar to not leave the country as long as Shirkuh remained there, for a sum of 400,000 bezants. Hugh Grenier and William of Tyre were sent on an embassy to ratify the treaty.[6]

Afterwards, the Crusaders started to build a bridge over the Nile in March 1167, but the Syrian archers prevent the end of the work. However, Shirkuh's army remained garrisoned outside the pyramids of Giza, because leaving the place would allow the crusaders to cross the Nile and take it from behind. A Syrian detachment sent for supplies north of Cairo was defeated by Miles of Plancy, causing discouragement in Shirkuh's army, as reinforcements arrive led by Humphrey II of Toron and Philip of Milly. The combined Fatimid-crusader army contemplated the next move and tried to cross the Nile further north using an island, and Shirkuh, deeming his position very precarious, withdrew to Upper Egypt.[7]

Amalric and Shawar left two detachments in Lower Egypt, one commanded by Hugh of Ibelin[b] to defend Cairo along with the sultan's son Kamil, while the other commanded by Gérard de Pougy, marshal of Jerusalem and another son of Shawar to hold Giza and set out in pursuit of Shirkuh. The Fatimid-crusader army followed to the Battle of al-Babein, where fighting was bloody but inconclusive. Even so, the crusader-Fatimids pursued the Syrians, whose plan to use Alexandria as a port came to nothing when the crusader fleet arrived. The people of Alexandria decided to open the city gates to Shirkuh without resistance, as Shawar was not popular there. The city was not ready for war, supplies were rapidly depleting, and the besieged was threatened with famine. Leaving the city to his nephew Saladin, Shirkuh left to Upper Egypt, hoping that part of the opposing army would follow him, but the maneuver did not materialize. At Alexandria, the besieged troops agreed to leave Egypt alone in return for a crusader withdrawal in August 1167.[8] Amalric left with a favorable treaty resulting in Egyptian tribute to Jerusalem and a friendly Shawar in control. The Crusaders had also left a small garrison in Alexandria, and Shawar had to pay King Amalric, 100,000 bezants each year, through the Alexandrian garrison.[9] However, while waiting for the payment of the agreed sum, Amalric delegated a representative to the court of Cairo and also installed a garrison there, putting Egypt under a Crusader protectorate.[10]

Fourth Crusader invasion, 1168–1169[]

The presence of a Frankish adviser at the court of the Caliph, a garrison in Cairo, as well as officials responsible for collecting the indemnities increased the discontent of the Egyptian people, because it implied additional taxes. Members of the court began to regard the alliance with Nur ad-Din as a lesser evil. The Frankish knights and officials became worried and began to send distress messages to Amalric. The latter hesitated, because he was negotiating an alliance with Byzantines for the conquest of Egypt, but a large fraction of his entourage pushed him to intervene immediately.[11]

At this point in time the crusaders should have focused on strengthening their position against Syria, but instead Amalric was tempted by Gilbert of Assailly, Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller, who provided five hundred knights and five hundred Turcopoles to attack Egypt and take it.[12] Manuel Komnenos received the idea well. However, the Venetian fleet, which at that time often operated in the eastern Mediterranean, refused to take part in the Egyptian campaigns because they did not want to jeopardize their trade relations with Egypt by war.

The alliance between the Crusaders and Byzantines was still being finalized when Amalric who utilized the fact that the vizier did not pay the agreed tribute to the Crusaders in Alexandria in time as an excuse, launched a quick attack against Bilbeis in November 1168,[c] massacring the population.[d] This outraged the Coptic population of Egypt and led to them ending their support of the Crusaders.[14] Shawar appealed to Damascus and Shirkuh returned. Meanwhile, Amalric's fleet after taking Tanis, where the bloodshed was repeated, could not go up the Nile and was ordered to withdraw. When faced with an imminent attack by Amalric, Shawar ordered the burning of his own capital city, Fustat, to keep it from falling into Amalric's hands. According to the Egyptian historian Al-Maqrizi (1346–1442):

Shawar ordered that Fustat be evacuated. He forced [the citizens] to leave their money and property behind and flee for their lives with their children. In the panic and chaos of the exodus, the fleeing crowd looked like a massive army of ghosts.... Some took refuge in the mosques and bathhouses...awaiting a Christian onslaught similar to the one in Bilbeis. Shawar sent 20,000 naphtha pots and 10,000 lighting bombs [mish'al] and distributed them throughout the city. Flames and smoke engulfed the city and rose to the sky in a terrifying scene. The blaze raged for 54 days.

— [15]

Later on, Amalric demanded tribute from Shawar for exchange for his withdrawal, which would be a million bezants, but the approach of Shirkuh forces forced him to lower his demands and give up half of the tribute.[16] On 2 January 1169, the troops of Amalric withdrew from the vicinity of Cairo.[17][e] Later that month, Shirkuh entered Cairo and had the untrustworthy Shawar executed. He himself died two months later and his nephew, Saladin, took power as regent.

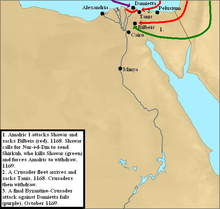

Siege of Damietta[]

In 1169, Andronikos Kontostephanos was appointed commander of a fleet carrying a Byzantine army to invade Egypt in alliance with the forces of Amalric. The campaign had been planned possibly since the marriage of Amalric with Manuel's great-niece Maria in 1167.

According to the chronicler William of Tyre: 150 galleys, sixty horse-carriers and a dozen dromons specially constructed to carry siege engines. The fleet set sail from the port of in the Dardanelles on 8 July 1169. After defeating a small Egyptian scouting squadron near Cyprus, Kontostephanos arrived at Tyre and Acre in late September to find that Amalric had undertaken no preparations whatsoever. The delays on the part of the Crusaders infuriated Kontostephanos and sow mistrust among the ostensible allies.[18][f]

It was not until mid-October that the combined armies and fleets set forth, arriving at Damietta two weeks later. The Christians delayed three days in attacking the city, allowing Saladin[g] to hastily move in troops and supplies. Damietta's defenders stretched strong chains across the Nile to prevent the Navy from attacking directly.[21] The siege was prosecuted with vigour on both sides, with Kontostephanos and his men constructing huge siege towers, but the besiegers were hampered by the growing mistrust between Byzantines and Crusaders, especially as the Byzantines' supplies dwindled, and Amalric refused to share his own with them but sold them at exorbitant prices.[22] However, Byzantines had urged the Franks to attack the city, but Amalric hesitated and did not want to risk great losses.[20] In addition, winter rains occurred in December weakened the attackers' combat readiness.

Exasperated by the dragging-on of the siege and the suffering of his troops, Kontostephanos once again disobeyed Manuel's instructions ordering him to obey Amalric in all things, and launched with his troops a final attack on the city. As the Byzantines were about to storm the walls, Amalric stopped them by announcing that a negotiated surrender of Damietta had just taken place.[23] The discipline and cohesion of the Byzantine army almost instantly disintegrated after the news of the peace deal were announced, with troops burning the engines and boarding the ships in groups without order. Left with only six ships, Kontostephanos accompanied Amalric back to Palestine, returning home with part of his army by land through the crusader states of the Levant, while about half of the Byzantine ships that had sailed from Damietta was lost in a series of storms on its return journey, with the last ships arriving in their home ports only in late spring 1170.[24]

Aftermath[]

In 1171, after the death of Caliph Al-Adid, Saladin proclaimed himself Sultan while the crusaders under Amalric were forced to retreat, having lost many men due to disease and warfare. The Knights Hospitaller became bankrupt after the operation but made a quick recovery financially. The same could not be said for the kingdom.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem, surrounded by enemies, now faced inevitable defeat. Saladin could raise armies potentially numbering 100,000 or more with Syria and Egypt under his control. Nur ad-Din however was still alive until 1174 and Saladin's power in Egypt was seen as a rebellion against his vassalage to Nur ad-Din. After the latter's death Syria and Egypt remained united. A few crusader victories, notably at Montgisard and a failed Ayyubid siege of Tiberias allowed the crusaders to stave off defeat until 1187. By 1189 the crusader realm had been diminished beyond all strength and relied increasingly on politically motivated and inexperienced western reinforcements.

However, after the fall of Jerusalem in 1187, the focus of the crusaders shifted decisively towards Egypt and less so towards the Levant. This can be seen in the Third Crusade, where Richard the Lionheart recognized the importance of Egypt and twice suggested an invasion of the region. An assault against the Levant could not succeed without the resources and manpower of Egypt, which currently gave the Islamic powers in the region a decisive advantage. The Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, Ninth and Alexandrian crusades all had Egypt as the intended target.

During the Fifth Crusade (1218–1221) a large force of crusaders led by the papal legate Pelagio Galvani and John of Brienne took Damietta. The expeditionary force included French, German, Flemish and Austrian crusaders and a Frisian fleet. The army marched on Cairo but was cut off by flooding of the Nile and the campaign ended in disaster with Pelagio forced to surrender with what remained of his army.

During the Seventh Crusade King Louis IX of France invaded Egypt (1249–1250) and after occupying Damietta he marched towards Cairo. However the forces led by Robert I, Count of Artois were defeated at the Battle of Al Mansurah and then King Louis and his main army were defeated at the Battle of Fariskur where his entire army was either killed or captured. The king suffered the humiliation of having to pay an enormous ransom for his freedom.

The temporary victories were followed by defeats, evacuations or negotiations—ultimately amounting to nothing. By 1291, Acre, the last major crusader fortress in the Holy Land, fell to the forces of the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt, and any remaining territories on the mainland were lost over the next decade.

Notes[]

- ^ In the meantime, Manuel Komnenos was in the Balkans.

- ^ Hugh was the first crusader ever to see the Fatimid sultan's palace in Cairo.

- ^ At the siege of Bilbeis during the same Egyptian campaign, according to Ibelin family tradition, Hugh's life was saved by Philip of Milly, after breaking his leg and falling under his horse.[13]

- ^ William IV, Count of Nevers intended to join the invasion, but died shortly afterwards in Acre. However, most of his knights participated in Amalric's campaign, and were probably responsible for the massacre of the population of Bilbeis.

- ^ Amalric's army had fought a pitched battle against the Muslims at Cairo, but they did not have the resources to conquer Egypt and were forced to retreat.

- ^ Having suffered heavy losses in the last campaign, the Crusaders needed some time to replenish their troops.[19]

- ^ Saladin was surprised by the attack on Damietta, as he was expecting an attack on Bilbeis.[20]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Canard 1965, p. 318.

- ^ Grousset 1935, pp. 430–431.

- ^ Gibb 2006, p. 8.

- ^ "Letter from Aymeric, Patriarch of Antioch, to Louis VII, King of France (1164)". De Re Militari. 4 March 2013.

- ^ Grousset 1935, pp. 456–458.

- ^ Grousset 1935, pp. 458–460.

- ^ Grousset 1935, pp. 464–466.

- ^ Grousset 1935, pp. 466–476.

- ^ Duggan 1963, p. 113.

- ^ Grousset 1935, pp. 479–480.

- ^ Grousset 1935, pp. 484–497.

- ^ Delaville Le Roulx 1904, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Barber 2003, p. 61.

- ^ Bridge 1982, p. 131.

- ^ Zayn Bilkadi (January–February 1995). "The Oil Weapons". Saudi Aramco World. pp. 20–27. Archived from the original on 2011-06-09. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ Delaville Le Roulx 1904, p. 72.

- ^ Josserand 2009, p. 390.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 261–263.

- ^ Bridge 1982, p. 132.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bridge 1982, p. 133.

- ^ Duggan 1963, p. 115.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 262–266.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 266–269.

- ^ Varzos 1984b, pp. 269–270.

Sources[]

- Barber, Malcolm (2003). Peter Edbury; Jonathan Phillips (eds.). The career of Philip of Nablus in the kingdom of Jerusalem. The Experience of Crusading, vol. 2: Defining the Crusader Kingdom. Cambridge University Press.

- Bridge, Antony (1982). The Crusades. Franklin Watts.

- Canard, Marius (1965). "Ḍirg̲h̲ām". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 317–319. OCLC 495469475.

- Duggan, Alfred (1963). The Story of the Crusades 1097–1291. Faber & Faber.

- Gibb, Sir Hamilton (2006). The Life of Saladin. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-86356-928-9.

- Grousset, René (1935). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem - II. 1131-1187 (in French). Paris: Perrin.

- Delaville Le Roulx, Joseph (1904). Les Hospitaliers en Terre Sainte et à Chypre (1100-1310) (in French). Paris E. Leroux.

- Josserand, Philippe (2009). Prier et combattre: dictionnaire européen des ordres militaires au Moyen Âge (in French). Fayard. ISBN 9782213627205.

- Varzos, Konstantinos (1984). Η Γενεαλογία των Κομνηνών [The Genealogy of the Komnenoi] (PDF) (in Greek). B. Thessaloniki: Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Thessaloniki. OCLC 834784665.

- Invasions of Egypt

- 12th-century conflicts

- 12th century in the Fatimid Caliphate

- Military history of the Fatimid Caliphate

- Wars involving the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Battles involving the Byzantine Empire

- Battles involving the Principality of Antioch

- Battles involving the Knights Hospitaller

- Battles involving the Knights Templar

- Battles of Saladin

- 1160s in the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Egypt under the Fatimid Caliphate