Cthulhu

| Cthulhu | |

|---|---|

| Cthulhu Mythos character | |

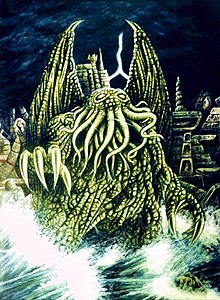

Illustration of Cthulhu from 2006 | |

| First appearance | "The Call of Cthulhu" (1928) |

| Created by | H. P. Lovecraft |

| In-universe information | |

| Species | Great Old One |

| Title |

|

| Family |

|

Cthulhu is a fictional cosmic entity created by writer H. P. Lovecraft. It was first introduced in his short story "The Call of Cthulhu",[2] published by the American pulp magazine Weird Tales in 1928. Considered a Great Old One within the pantheon of Lovecraftian cosmic entities, this creature has since been featured in numerous popular culture references. Lovecraft depicts it as a gigantic entity worshipped by cultists, in a shape like a green octopus, dragon, and a caricature of human form. Its name was given to the Lovecraft-inspired universe, the Cthulhu Mythos, where it exists with its fellow entities.

Etymology, spelling, and pronunciation[]

Invented by Lovecraft in 1928, the name Cthulhu was probably chosen to echo the word chthonic (Ancient Greek "of the earth"), as apparently suggested by Lovecraft himself at the end of his 1923 tale "The Rats in the Walls".[3] The chthonic, or earth-dwelling, spirit has precedents in numerous ancient and medieval mythologies, often guarding mines and precious underground treasures, notably in the Germanic dwarfs and the Greek Chalybes, Telchines, or Dactyls.[4]

Lovecraft transcribed the pronunciation of Cthulhu as Khlûl′-hloo, and said, "the first syllable pronounced gutturally and very thickly. The 'u' is about like that in 'full', and the first syllable is not unlike 'klul' in sound, hence the 'h' represents the guttural thickness"[5] (see discussion linked below). S. T. Joshi points out, however, that Lovecraft gave different pronunciations on different occasions.[6] According to Lovecraft, this is merely the closest that the human vocal apparatus can come to reproducing the syllables of an alien language.[7] Cthulhu has also been spelled in many other ways, including Tulu, Katulu, and Kutulu.[8] The name is often preceded by the epithet Great, Dead, or Dread.

Long after Lovecraft's death, Chaosium, publishers of the Call of Cthulhu role-playing game, influenced modern pronunciation with the statement, "we say it kuh-THOOL-hu", even while noting that Lovecraft said it differently.[9] Others use the pronunciation Katulu or Kutulu or /kəˈtuːluː/[10]

Description[]

In "The Call of Cthulhu", H. P. Lovecraft describes a statue of Cthulhu as: "A monster of vaguely anthropoid outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind."[11]

Cthulhu is said to resemble a green octopus, dragon, and a human caricature, hundreds of meters tall, with webbed, human-looking arms and legs and a pair of rudimentary wings on its back.[11] Its head is depicted as similar to the entirety of a gigantic octopus, with an unknown number of tentacles surrounding its supposed mouth.

Publication history[]

The short story that first mentions Cthulhu, "The Call of Cthulhu", was published in Weird Tales in 1928, and established the character as a malevolent entity, hibernating within R'lyeh, an underwater city in the South Pacific. The imprisoned Cthulhu is apparently the source of constant subconscious anxiety for all mankind, and is also the object of worship, both by many human cults (including within New Zealand, Greenland, Louisiana, and the Chinese mountains) and by other Lovecraftian monsters (called Deep Ones[12] and Mi-Go[13]). The short story asserts the premise that, while currently trapped, Cthulhu will eventually return. His worshippers chant "Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah'nagl fhtagn" ("In his house at R'lyeh, dead Cthulhu waits dreaming.")[11]

Lovecraft conceived a detailed genealogy for Cthulhu (published as "Letter 617" in Selected Letters)[1] and made the character a central reference in his works.[14] The short story "The Dunwich Horror" (1928)[15] refers to Cthulhu, while "The Whisperer in Darkness" (1930) hints that one of his characters knows the creature's origins ("I learned whence Cthulhu first came, and why half the great temporary stars of history had flared forth.")[13] The 1931 novella At the Mountains of Madness refers to the "star-spawn of Cthulhu", who warred with another race called the Elder Things before the dawn of man.[16]

August Derleth, a correspondent of Lovecraft's, used the creature's name to identify the system of lore employed by Lovecraft and his literary successors, the Cthulhu Mythos. In 1937, Derleth wrote the short story "The Return of Hastur", and proposed two groups of opposed cosmic entities:

the Old or Ancient Ones, the Elder Gods, of cosmic good, and those of cosmic evil, bearing many names, and themselves of different groups, as if associated with the elements and yet transcending them: for there are the Water Beings, hidden in the depths; those of Air that are the primal lurkers beyond time; those of Earth, horrible animate survivors of distant eons.[17]:256

According to Derleth's scheme, "Great Cthulhu is one of the Water Elementals" and was engaged in an age-old arch-rivalry with a designated air elemental, Hastur the Unspeakable, described as Cthulhu's "half-brother."[17]:256, 266 Based on this framework, Derleth wrote a series of short stories published in Weird Tales (1944–'52) and collected as The Trail of Cthulhu, depicting the struggle of a Dr. Laban Shrewsbury and his associates against Cthulhu and his minions. In addition, Cthulhu is referenced in Derleth's 1945 novel The Lurker at the Threshold published by Arkham House. The novel can also be found in The Watchers Out of Time and Others, a collection of stories from Derleth's interpretations of Lovecraftian Mythos published by Arkham House in 1974.

Derleth's interpretations have been criticized by Lovecraft enthusiast Michel Houellebecq, among others. Houellebecq's H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life (2005) decries Derleth for attempting to reshape Lovecraft's strictly amoral continuity into a stereotypical conflict between forces of objective good and evil.[18]

In John Glasby's "A Shadow from the Aeons", Cthulhu is seen by the narrator roaming the riverbank near Dominic Waldron's castle, and roaring.[19] The god appears totally different from its depiction by other authors.[citation needed]

The character's influence also extended into gaming literature; games company TSR included an entire chapter on the Cthulhu mythos (including character statistics)

in the first printing of Dungeons & Dragons sourcebook Deities & Demigods (1980). TSR, however, were unaware that Arkham House, which asserted copyright on almost all Lovecraft literature, had already licensed the Cthulhu property from game company Chaosium. Although Chaosium stipulated that TSR could continue to use the material if each future edition featured a published credit to Chaosium, TSR refused and the material was removed from all subsequent editions.[20]

Legacy[]

This article appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. (July 2021) |

Games[]

In 1981, Chaosium released their role-playing game Call of Cthulhu. This game may have greatly contributed to making the works of Lovecraft known to a bigger audience. It has now reached its seventh edition with a large amount of supplementary material also available, and has won several major gaming awards. In 1987, Chaosium published the co-operative adventure board game Arkham Horror, based on the same background, which has since been reissued by other publishers. In 1996, they released a collectible card game, Mythos.

In 2004, Fantasy Flight Games began a long-term relationship with Chaosium and released a collectible card game, which has been remarketed in a new format (living card game) in 2008 as Call of Cthulhu: The Card Game. This was the first of a collection of games by this publisher, and the only one in its family that was not co-operative. The company have followed since a fully rebuilt Arkham Horror (2005, 2018), the dice game Elder Sign (2011), the dungeon (or mansion) crawler Mansions of Madness (2011, 2016), a pulp version of Arkham Horror with Eldritch Horror (2013), a storytelling living card game Arkham Horror: The Card Game (2016), and a deduction game Arkham Horror: Final Hour (2019).[21]

In 2006, Bethesda Softworks, Ubisoft, and 2K Games jointly published a game by Headfirst Productions, Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth, based on the works of Lovecraft. Cthulhu himself does not appear, as the main antagonists of the game are the Deep Ones from The Shadow Over Innsmouth, and the sea god Dagon, but his presence is alluded to several times, and viewing a statue of him in one of the temples will undermine the player's sanity. Also, one of Cthulhu's Star Spawn, of similar hideous appearance, appears as a late-game enemy.[22]

On March 19, 2007, Steve Jackson Games released an iteration of their card game Munchkin called Munchkin Cthulhu.[23] The game presents Cthulhu and its surrounding mythos with a cartoon-art style and comedic tone, heavily playing upon themes of madness and cultism. Great Cthulhu features as a standalone monster in the deck, alongside various parodies of Lovecraft's creatures.[24] Cthulhu is depicted as an overweight, bright green creature with a large, bulbous head, and a pair of disproportionately small wings.[25]

The Ukrainian video game series S.T.A.L.K.E.R. has a Cthulhu-inspired mutant called Bloodsucker.

Cthulhu is the main inspiration for the zombies in the video game Call of Duty: Black Ops 3.[26]

The massively multiplayer online role-playing game World of Warcraft has numerous references to Cthulhu and the Mythos, including an early raid boss called C'Thun, and more recently, one of the game's "Old Gods" named N'Zoth resting in a sunken city.[27]

In Scribblenauts (2009), Cthulhu is summonable. He is much smaller than described in Lovecraft's works, but is much stronger than most other aggressive objects.

Cthulhu Saves the World (2010) features Cthulhu in the unusual role of protagonist. A prequel, Cthulhu Saves Christmas, was released in 2019.

In 2013, Treefrog Games released A Study in Emerald, a board game based upon a short story written by Neil Gaiman that blends Cthulhu Mythos and Sherlock Holmes.[28]

In 2014, the spell "Call of Khrulhu" was added to Wizard101, a massively multiplayer online role-playing game. While not spelled the same, the spell takes inspiration from Lovecraft's aforementioned tale, "The Call of Cthulhu."

In 2015, the author of Chaosium's 1981 role-playing game, Sandy Petersen, designed an asymmetrical board game: Cthulhu Wars.

In the 2015 video game Bloodborne, game director Hidetaka Miyazaki decided to incorporate ideas and themes from Lovecraft's novels such as creatures based on Lovecraft's Great Old Ones.[29]

In 2016, Z-Man Games released an alternate version of the board game Pandemic. This new adaptation, Pandemic: Reign of Cthulhu, is set in the Cthulhu Mythos and explorers race to save the world before Cthulhu returns.[30]

In the 2016 Android video game Flappy monsters of Lovecraft, a flappy style game, players can take control of Cthulhu.

In September 2017 Alessandro Guzzo released The Land of Pain, a first person survival horror game set in the Cthulhu universe

In 2018, a survival horror role-playing video game called Call of Cthulhu: The Official Video Game was developed for PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and Windows PC.

On 2 April 2018, an asymmetrical survival horror video game called Identity V was launched by NetEase. The game includes hunter characters from Cthulhu Mythos. The game can be played through both mobile and PC.

In 2019, CMON Limited released the board game Cthulhu: Death May Die.

In June 2019, an open-world horror detective game called The Sinking City, which is based on Cthulhu Mythos, was released for Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 4, and Xbox One. It was also released for Nintendo Switch in September of that year.

In 2020, Cthulhu was released as a playable character in the MOBA Smite.

Politics[]

Cthulhu has appeared as a parody candidate in several elections, including the 2010 Polish presidential election and the 2012 and 2016 US presidential elections.[31][32] The faux campaigns usually satirize voters who claim to vote for the "lesser evil". In 2016, the troll account known as "The Dark Lord Cthulhu" submitted an official application to be on the Massachusetts Presidential Ballot. The account also raised over $4000 from fans to fund the campaign through a gofundme.com page. Gofundme removed the campaign page and refunded contributions. The Cthulhu Party[33] (UK), another pseudo-political organisation, claim to be 'Changing Politics for Evil', parodying the Brexit Party's 'Changing Politics for Good'; a member of The Cthulhu Party holds the position of Mayor of Blists Hill. Another organization, Cthulhu for America, ran during the 2016 American presidential election, drawing comparisons with other satirical presidential candidates such as Vermin Supreme.[34] The organization had a platform that included the legalization of human sacrifice, driving all Americans insane, and an end to peace.[35]

Science[]

The Californian spider species Pimoa cthulhu, described by Gustavo Hormiga in 1994,[36] and the New Guinea moth species Speiredonia cthulhui, described by Alberto Zilli and Jeremy D. Holloway in 2005,[37] are named after Cthulhu.

Two microorganisms that assist in the digestion of wood by termites have been named after Cthulhu and Cthulhu's "daughter" Cthylla: Cthulhu macrofasciculumque and Cthylla microfasciculumque.[38]

In 2014, science and technology scholar Donna Haraway gave a talk entitled "Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Staying with the Trouble", in which she proposed the term "Chthulucene" as an alternative for the concept of the Anthropocene era, due to the entangling interconnectedness of all supposedly individual beings.[39] Haraway has denied any indebtedness to Lovecraft's Cthulhu, claiming that her "chthulu" is derived from Greek khthonios, "of the earth".[40] However, the Lovecraft character is much closer to her coined term than the Greek root, and her description of its meaning coincides with Lovecraft's idea of the apocalyptic, multitentacled threat of Cthulhu to collapse civilization into an endless dark horror: "Chthulucene does not close in on itself; it does not round off; its contact zones are ubiquitous and continuously spin out loopy tendrils."[41]

In 2015, an elongated, dark region along the equator of Pluto, initially referred to as "the Whale", was proposed to be named "Cthulhu Regio", by the NASA team responsible for the New Horizons mission.[42] It is now known as "Cthulhu Macula".[43][44]

In April 2019, Imran A. Rahman and a team announced in Proceedings of the Royal Society B the discovery of Sollasina cthulhu, an extinct member of the ophiocistioids group.[45]

Film and TV[]

Several films and television programs feature the threat of Cthulhu returning to dominate the Universe. A notable example is three episodes of the adult cartoon series South Park in which Eric Cartman turns out to be so irredeemably evil that he is able to tame Cthulhu and direct him to annihilate personal enemies. In those episodes ("Coon 2: Hindsight", "Mysterion Rises", and "Coon vs. Coon & Friends") Cthulhu is faithfully represented as the monstrous tentacle-mouthed god-like being Lovecraft describes.

In the popular adult animated science-fiction sitcom Rick and Morty, a depiction of Cthulhu can be seen in the opening sequence, immediately prior to the title card.[46] In Cartoon Network's animated show The Grim Adventures of Billy and Mandy, Cthulhu has a dedicated double-length episode called "Prank Call of Cthulhu". Cthulhu also made a short appearance at the beginning of The Simpsons episode "Treehouse of Horror XXIX".

In the Justice League animated series episode "The Terror Beyond" under Warner Bros, Cthulhu is shown as an invader from an interdimensional world to earth where Justice League team members fight with Cthulhu. In season two, episodes 18 and 19 of Gravity Falls, Cthulhu is briefly seen destroying a giant ear with a mouth-laser and then walking, respectively.[47][48]

On October 27, 1987, Cthulhu appeared in season two, episode 28 of The Real Ghostbusters animated cartoon entitled "The Collect Call of Cathulhu", in which the Ghostbusters went up against the Spawn, and Cult, of Cthulhu.[49]

Cthulhu is featured in Arcana Studio's Howard Lovecraft animated trilogy beginning with Howard Lovecraft and the Frozen Kingdom, and ending with the upcoming Kingdom of Madness.[50][51]

The Call of Cthulhu is a 2005 independent silent-film adaptation of the eponymous short story, produced by Sean Branney and Andrew Leman.[citation needed]

Cast a Deadly Spell is a 1991 noir film featuring private detective H. Philip Lovecraft, in a fictional Los Angeles, where magic is real, monsters and mythical beasts stalk the back alleys, zombies are used as cheap labor, and everyone—except Lovecraft—uses magic every day. The plot revolves around a scheme to use a copy of the Necronomicon to summon an ancient god that might be Cthulhu.[citation needed]

The 2007 film Cthulhu is loosely based on Lovecraft's 1936 novella The Shadow over Innsmouth, which is a part of the Cthulhu Mythos.[citation needed]

The creatures in the 2018 Netflix film Bird Box are strongly implied to be related to Cthulhu.[52]

Cthulhu appears in season four, episode seven of The Venture Bros., battling the Order of the Triad.[citation needed]

Cthulhu is mentioned in season two, episode 14 of Night Gallery, "Professor Peabody's Last Lecture".[citation needed]

Cthulhu appears in the climax of the film Underwater, worshipped by a civilization of underwater humanoids.[53]

Cthulhu, or at least his star-spawn, is set to appear in Lovecraft Country.[54]

Music[]

Heavy metal band Metallica referenced Cthulhu in the song "Dream No More" from their 2016 album Hardwired... To Self-Destruct,[55] as well as on the 1984 album Ride the Lightning with the instrumental track "The Call of Ktulu", inspired by H. P. Lovecraft's novella The Shadow over Innsmouth, which was introduced to the rest of the band by Cliff Burton,[56] and on the 1986 album Master of Puppets with the song "The Thing That Should Not Be" (whose lyrics are inspired by The Shadow over Innsmouth and contain partial quotes from "The Call of Cthulhu").[57]

The fifth studio album by Canadian electronic music producer deadmau5 features the song "Cthulhu Sleeps".

American metal band The Acacia Strain features a song titled "Cthulhu" on their album Continent.

The second album of British steampunk band The Men That Will Not Be Blamed for Nothing features the song "Margate Fhtagn". The song describes the band's meeting with Cthulhu while on holiday in Margate.[58]

English extreme metal band Cradle of Filth's fourth album, Midian, features a song titled "Cthulhu Dawn",[59] although the lyrics seem to have nothing to do with Lovecraft's sea-monster.

The songs "The Watchman" and "Last Exit for the Lost", by British gothic rock band Fields of the Nephilim, both reference Cthulhu (or Kthulhu as it is spelled on the album's inner sleeve).[60]

British progressive rock band CARAVAN released the song "C'Thlu Thlu" on the album For Girls Who Grow Plump in the Night (1973).

The penultimate track on the 2011 self-titled debut album by New Zealand sludge metal band Beastwars is titled "Cthulhu".

The album Stairway To Valhalla by Nanowar of Steel features a song titled "The Call of Cthulhu".

The song "Cthulhu" by German power metal and "SUPERHEROMETAL" band mentions the city of Rlyeh.

The song "Angel of Disease" by American death metal band Morbid Angel references the Ancient Ones, Cthulhu, and Shub-Niggurath.

British synthwave band, Gunship, released the song "Cthulhu" in 2019, featuring a quote from Lovecraft's The Call of Cthulhu and Other Dark Tales[61] narrated by horror-film director, Corin Hardy. [62]

Theater[]

The story was adapted for the stage by Oregon-based theater company Puppeteers for Fears, who performed "The Call of Cthulhu" as Cthulhu: the Musical! a feature-length rock-and-roll musical comedy performed with puppets, with the Cthulhu puppet being the largest and most complex. The script and songs were written by playwright Josh Gross,[63] and after a successful run in Ashland, Oregon, the production toured the west coast in 2018, including a sold-out run at the Hollywood Fringe Festival. Of the show, The Portland Mercury wrote, "You haven't truly experienced Lovecraft's madness until you've experienced it in its truest form: As a puppet musical."[64]

The 2019 StarKid Productions horror-comedy musical Black Friday's main antagonist is an entity named Wiggly who takes the form of a plush toy that strongly resembles Cthulhu. The opening number "Wiggly Jingle" features the lyric "He's an underwater creature from outta this world", which is a direct reference to Cthulhu's origins.[65] In the second act, Wiggly is revealed to be a much larger cosmic entity who was using the plush toys and the hysteria they caused to destroy humanity. Wiggly's larger form is a loose-form puppet made out of the set dressing, but still has the recognizable Cthulhu shape.[66] The musical was written by Matt and Nick Lang with lyrics and music by Jeff Blim. Black Friday successfully ran at the Hudson Mainstage Theater in Los Angeles, California from October 31, 2019 to December 8, 2019.

Other[]

Toy versions of Cthulhu have been released in support of games. A plush Cthulhu has become a kawaii cultural meme.[67]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lovecraft, H. P. (1967). Selected Letters of H. P. Lovecraft IV (1932–1934). Sauk City, Wisconsin: Arkham House. Letter 617. ISBN 0-87054-035-1.

- ^ "{title}". Archived from the original on 2018-08-02. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ^ Callaghan, Gavin (2013). H. P. Lovecraft's Dark Arcadia: The Satire, Symbology and Contradiction. McFarland. p. 192. ISBN 978-1476602394.

- ^ Kearns, Emily (2011). Finkelberg, Margalit (ed.). "Chthonic deities". The Homer encyclopedia. Wiley. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Lovecraft, H. P. Selected Letters V. pp. 10–11.

- ^ Joshi, S. T. "The Call of Cthulhu". The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. note 9.

- ^ "Cthul-Who?: How Do You Pronounce 'Cthulhu'?", Crypt of Cthulhu #9

- ^ Harms, Thomas. "Cthulhu" and "PanCthulhu". The Encyclopedia Cthulhiana. p. 64.

- ^ Petersen, Sandy; Willis, Lynn; Herber, Keith (1981). Call of Cthulhu (2 ed.). Oakland, California: Chaosium.:What's in this box?

- ^ e.g. the video game Call of Cthulhu[1] Archived 2020-09-01 at the Wayback Machine and season 14 of South Park.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c s:The Call of Cthulhu

- ^ s:The Shadow Over Innsmouth

- ^ Jump up to: a b s:The Whisperer in Darkness

- ^ Angell, George Gammell (1982). Price, Robert M. (ed.). "Cthulhu Elsewhere in Lovecraft". Crypt of Cthulhu (9): 13–15. ISSN 1077-8179.

- ^ s:The Dunwich Horror

- ^ Lovecraft, H. P. At the Mountains of Madness. p. 66. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2011-04-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Derleth, August. "The Return of Hastur". In Price, Robert M. (ed.). The Hastur Cycle.

- ^ Bloch, Robert. "Heritage of Horror". The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre.

- ^ Glasby, John S. (2015-08-09). The Brooding City and Other Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos. Ramble House.

- ^ "Deities & Demigods, Legends & Lore". The Acaeum. Archived from the original on 2010-09-03. Retrieved 2010-05-10.

- ^ "Arkham Horror Files at Fantasy Flight Games". www.fantasyflightgames.com. Archived from the original on 2020-11-23. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "Bethesda to publish Call of Cthulhu". Archived from the original on 2018-08-02. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ^ "Steve Jackson Games: Previously Shipped". www.sjgames.com. Archived from the original on 2018-05-10. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

- ^ "Munchkin® Cthulhu™ – Card List". www.worldofmunchkin.com. Archived from the original on 2018-05-10. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

- ^ "Daily Illuminator: Munchkin Cthulhu Guest Artist Edition: Then And Now". www.sjgames.com. Archived from the original on 2018-05-10. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

- ^ Fulton, Will (July 10, 2015). "Jeff Goldblum, Heather Graham, and Ron Perlman lead Black Ops 3's Lovecraft Noir Zombie mode". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Patch 4.3 Raid Preview: Dragon Soul - WoW". World of Warcraft. Archived from the original on 2018-09-14. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ^ "Neil Gaiman short stories". www.neilgaiman.com. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "[Bloodborne] Exclusive Interview with Jun Yoshino!". playstation.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- ^ "Pandemic: ROC - The Old Ones Series - Hastur". zmangames.com. Z-Man Games. April 14, 2016. Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ^ "Cthulhu for America". Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 3 Aug 2016.

- ^ "Cthulhu Dagon 2012". Archived from the original on 2016-10-14. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ "Log In or Sign Up to View". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 2019-09-29. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

- ^ Watson, Zebbie (June 16, 2016). "Who Is Behind Cthulhu For America?". Inverse. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Barnett, David (March 1, 2016). "Could Cthulhu trump the other Super Tuesday contenders?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Hormiga, G. (1994). "A revision and cladistic analysis of the spider family Pimoidae (Araneoidea: Araneae)" (PDF). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 549 (549): 1–104. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.549. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-13. Retrieved 2011-05-09.

- ^ Zilli, Alberto; Holloway, Jeremy D. & Hogenes, Willem (2005). "An Overview of the Genus Speiredonia with Description of Seven New Species (Insecta, Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)". Aldrovandia. 1: 17–36. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ James, Erick R.; Okamoto, Noriko; Burki, Fabien; Scheffrahn, Rudolf H.; Keeling, Patrick J. (2013-03-18). Badger, Jonathan H. (ed.). "Cthulhu Macrofasciculumque n. g., n. sp. and Cthylla Microfasciculumque n. g., n. sp., a Newly Identified Lineage of Parabasalian Termite Symbionts". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e58509. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...858509J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058509. PMC 3601090. PMID 23526991.

- ^ Donna Haraway (9 May 2014). Donna Haraway, "Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene: Staying with the Trouble", 5/9/14. Vimeo, Inc. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-06.

- ^ Haraway, Donna (2016). Staying with the Trouble. Durham and London: Duke University Press. pp. 174n4. ISBN 978-0-8223-6224-1.

- ^ Wark, McKenzie (September 8, 2016). "Chthulucene, Capitalocene, Anthropocene". PublicSeminar.org. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-30.

- ^ Feltman, Rachel (14 July 2015). "New data reveals that Pluto's heart is broken". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2015-07-15. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ Amanda M. Zangari; et al. (November 2015). "New Horizons disk-integrated approach photometry of Pluto and Charon". AAS/Division for Planetary Sciences Meeting Abstracts #47. American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting #47, id.210.01. 47: 210.01. Bibcode:2015DPS....4721001Z.

- ^ Stern, S. A.; Grundy, W.; McKinnon, W. B.; Weaver, H. A.; Young, L. A. (2018). "The Pluto System After New Horizons". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 56: 357–392. arXiv:1712.05669. Bibcode:2018ARA&A..56..357S. doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-081817-051935. S2CID 119072504.

- ^ Rahman, Imran A.; Thompson, Jeffrey R.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Siveter, David J.; Siveter, Derek J.; Sutton, Mark D. (2019). "A new ophiocistioid with soft-tissue preservation from the Silurian Herefordshire Lagerstätte, and the evolution of the holothurian body plan" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1900): 20182792. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2792. PMC 6501687. PMID 30966985. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- ^ Pilot (Television production). Adult Swim. 2 December 2013. Event occurs at 2:30-2:33.

- ^ "Weirdmageddon Part 1". Gravity Falls (Television production). Disney XD. 26 October 2015. Event occurs at 5:30-5:35.

[Gideon Gleeful sees Cthulhu mouth-laser a giant ear to death]

- ^ "Weirdmageddon Part 2". Gravity Falls (Television production). Disney XD. 23 November 2015. Event occurs at 0:03-0:08.

[Cthulhu is seen walking, with the caption stating, ‘Weirdmageddon Day 4’]

- ^ "The Ghostbusters are an Antidote to Lovecraft's Dismal Worldview". 2014-09-11. Archived from the original on 2018-08-02. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ^ Howard Lovecraft and the Frozen Kingdom, archived from the original on 2018-08-20, retrieved 2018-09-17

- ^ Busch, Anita (2015-10-07). "Shout! Acquires All U.S. Rights To Arcana Studios' H.P. Lovecraft Animated Film". Deadline. Archived from the original on 2019-11-11. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- ^ Kyle Anderson (January 9, 2019). "Just How Cosmic Is BIRD BOX's Cosmic Horror?". Nerdist. Archived from the original on September 2, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Shannon Lewis (January 17, 2020). "Underwater Movie's Monster Is Cthulhu". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ John Squires (July 24, 2020). "Enough Teasing, Here's Cthulhu: New Trailer for HBO's "Lovecraft Country" is the One You've Been Waiting For". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on August 18, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ "Dream No More - Metallica". Metallica. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- ^ Joel., McIver (2009). To live is to die : the life and death of Metallica's Cliff Burton. Hammett, Kirk. (1st ed.). London: Jawbone Press. ISBN 9781906002244. OCLC 290435379.

- ^ "The Thing That Should Not Be - Metallica". Metallica. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- ^ "The Men That Will Not Be Blamed For Nothing". Wicked Spins Radio. 2012-03-19. Archived from the original on 2017-12-05. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- ^ "Cradle Of Filth - Midian". Discogs. Archived from the original on 2018-02-21. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- ^ Fields of the Nephilim, The Nephilim album, released 1988 by Situation Two/Beggars Banquet Records.

- ^ Lovecraft, H. P. (1999-10-01). S. T. Joshi (ed.). The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. London: Penguin Classics.

- ^ "Gunship feat. Corin Hardy - Cthulhu". Bandcamp. Retrieved 2021-03-26.

- ^ "Cthulhu: the Musical, Original Cast Recording, by Puppeteers for Fears". The Many Projects of Josh Gross. Archived from the original on 2018-07-18. Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- ^ "Cthulhu: The Musical!". Portland Mercury. Archived from the original on 2018-07-18. Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- ^ "Team StarKid – Tickle-Me Wiggly Jingle".

- ^ "Black Friday". Archived from the original on 2021-02-05. Retrieved 2021-01-09.

- ^ Ward, Rachel Mizsei (Summer 2013). "Plushies, My Little Cthulhu and Chibithulhu: The Transformation of Cthulhu from Horrific Body to Cute Body" (PDF). Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies. Trinity College Dublin (12): 87–106. ISSN 2009-0374. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

Further reading[]

- Bloch, Robert (1982). "Heritage of Horror". The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre (1st ed.). Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-35080-4.

- Burleson, Donald R. (1983). H. P. Lovecraft, A Critical Study. Westport, CT / London, England: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-23255-5.

- Burnett, Cathy (1996). Spectrum No. 3:The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art. Nevada City, CA, 95959 USA: Underwood Books. ISBN 1-887424-10-5.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Harms, Daniel (1998). "Cthulhu". The Encyclopedia Cthulhiana (2nd ed.). Oakland, CA: Chaosium. pp. 64–7. ISBN 1568821190.

- "Idh-yaa", p. 148. Ibid.

- "Star-spawn of Cthulhu", pp. 283 – 4. Ibid.

- Joshi, S. T.; Schultz, David E. (2001). An H. P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313315787.

- Lovecraft, Howard P. (1999) [1928]. "The Call of Cthulhu". In S. T. Joshi (ed.). The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. London, UK; New York, NY: Penguin Books. Archived from the original on November 26, 2009.

- Lovecraft, Howard P. (1968). Selected Letters II. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House. ISBN 0870540297.

- Lovecraft, Howard P. (1976). Selected Letters V. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House. ISBN 087054036X.

- Marsh, Philip. R'lyehian as a Toy Language – on psycholinguistics. Lehigh Acres, FL 33970-0085 USA: Philip Marsh.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Mosig, Yozan Dirk W. (1997). Mosig at Last: A Psychologist Looks at H. P. Lovecraft (1st ed.). West Warwick, RI: Necronomicon Press. ISBN 0940884909.

- Pearsall, Anthony B. (2005). The Lovecraft Lexicon (1st ed.). Tempe, AZ: New Falcon Pub. ISBN 1561841293.

- "Other Lovecraftian Products" Archived 2008-07-23 at the Wayback Machine, The H.P. Lovecraft Archive

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cthulhu (entity). |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Lovecraft, H. P. "The Call of Cthulhu". www.hplovecraft.com. Donovan K. Loucks. Retrieved 2020-04-15.

- Schema on Lovecraft’s »The Call of Ctuhulhu« and the Cthulhu Mythos

- Cthulhu Mythos deities

- Fictional characters with dream manipulation abilities

- Fictional monsters

- Fictional giants

- Fictional priests and priestesses

- Fictional telepaths

- Literary characters introduced in 1928

- Male literary villains

- New religious movement deities