Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were a historical group of people living in Central Europe and Scandinavia. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and early medieval Germanic languages and are thus equated at least approximately with Germanic-speaking peoples, although different academic disciplines have their own definitions of what makes someone or something "Germanic".[1] The Romans named the area in which Germanic peoples lived Germania, stretching West to East between the Vistula and Rhine rivers and north to south from Southern Scandinavia to the upper Danube.[2] In discussions of the Roman period, the Germanic peoples are sometimes referred to as Germani or ancient Germans, although many scholars consider the second term problematic, since it suggests identity with modern Germans. The very concept of "Germanic peoples" has become the subject of controversy among modern scholars, with some calling for its total abandonment.[3]

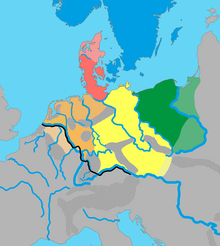

The earliest material culture that may be confidently ascribed to Germanic-speaking peoples is the Iron Age Jastorf Culture (6th to 1st centuries BCE), located in what is now Denmark and northeastern Germany; during this period metallurgy technology expanded in several directions. In contrast, Roman authors first described Germanic peoples near the Rhine at the time the Roman Empire established its dominance in that region. Under their influence the term came to cover a broader region stretching to the Elbe and beyond, which developed close relations both internally, and with the Romans. From the beginning of the Roman empire, the Germanic peoples were recruited into the Roman military where they often rose to the highest ranks. Roman efforts to integrate the large area between Rhine and Elbe ended around 16 CE, following the major Roman defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE. After their withdrawal from Germania, the Romans built a long fortified border known as the Limes Germanicus to defend against any incursions.[4] Further conflicts with the Germanic peoples include the Marcomannic Wars of Marcus Aurelius (166-180 CE). In the 3rd century the Germanic-speaking Goths dominated the Pontic Steppe, outside Germania, and launched a series of sea expeditions into the Balkans and Anatolia as far as Cyprus.[5][6] In the late 4th century CE, often termed the Migration period, many Germanic peoples entered the Roman Empire, where they eventually established their own independent kingdoms.

Archaeological sources suggest that Roman-era sources are not entirely accurate in their depiction of the Germanic way of life, which they portray as more primitive and simpler than it was. Archaeology instead shows a complex society and economy throughout Germania. Germanic-speaking peoples originally shared a common religion, Germanic paganism, which varied widely throughout the territory occupied by Germanic-speaking peoples. Over the course of Late Antiquity, most continental Germanic peoples and the Anglo-Saxons of Britain converted to Christianity, with the Saxons and Scandinavians only converting much later. Traditionally, the Germanic peoples have been seen as possessing a law dominated by the concepts of feuding and blood compensation. The precise details, nature, and origin of what is still normally called "Germanic law" are now controversial. Roman sources say that the Germanic peoples made decisions in a popular assembly (the thing), but also had kings and war-leaders. The ancient Germanic-speaking peoples probably shared a common poetic tradition, alliterative verse, and later Germanic peoples also shared legends originating in the Migration Period.

The publishing of Tacitus's Germania by humanists in the 1400s greatly influenced the emergent idea of "Germanic peoples". Later, scholars of the Romantic period such as Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm developed several theories about the nature of the Germanic peoples that were highly influenced by romantic nationalism. For such scholars, the "Germanic" and modern "German" were identical. Ideas about the early Germans were also highly influential among—and influenced and co-opted by—the Nazis, leading in the second half of the 20th century to a backlash against many aspects of earlier scholarship.

Terminology[]

Etymology[]

The etymology of the Latin word "Germani", from which Latin Germania and English "Germanic" are derived, is unknown, although several different proposals have been made for the origin of the name. Even the language from which it derives is a subject of dispute, with proposals of Germanic, Celtic, and Latin, and Illyrian origins.[7] Herwig Wolfram, for example, thinks "Germani" must be Gaulish.[8] Historian Wolfgang Pfeifer more or less concurs with Wolfram and surmises that the name Germani is likely of Celtic etymology, related in this case to the Old Irish word gair (neighbors) or could be tied to the Celtic word for their war cries gairm, which simplifies into "the neighbors" or "the screamers".[9] Regardless of its language of origin, the name was transmitted to the Romans via Celtic speakers.[10]

It is unclear that any people group ever referred to themselves as Germani.[11] Among German historians of classical antiquity, it is commonly supposed that Julius Caesar either invented or redefined the term as an ethnographical category.[12] By late antiquity, only peoples near the Rhine, especially the Franks, and sometimes the Alemanni, were called Germani by Latin or Greek writers.[13] By the end of the twentieth century, scholarship had demonstrated that authors in antiquity used the terms Germani, gentes Germani or Germania from ill-defined tradition rather than as a description of actual circumstances, basing them on very limited contemporary knowledge of the peoples described and their actual geographical locations.[14] Germani subsequently ceased to be used as a name for any group of people, and was only revived as such by the humanists in the 16th century.[11] Previously, scholars during the Carolingian period (8th-11th century) had already begun using Germania and Germanicus in a territorial sense to refer to East Francia.[15]

In modern English, the adjective "Germanic" is generally distinct from "German" in referring not to modern Germans but ancient Germani or the broader Germanic group.[16] In modern German, the ancient Germani are referred to as Germanen and Germania as Germanien, as distinct from modern Germans (Deutsche) and modern Germany (Deutschland). The direct equivalents in English are, however, "Germans" for Germani and "Germany" for Germania,[17] although the Latin "Germania" is also used. To avoid ambiguity, the Germani may instead be called "ancient Germans" or Germani, using the Latin term in English.[18][16]

Modern definitions and controversies[]

The modern definition of Germanic peoples developed in the 19th century, when the term "Germanic" was linked to the newly discovered Germanic languages, giving a new way of defining the Germanic peoples which came to be used in historiography and archaeology.[19][1] While Roman authors did not consistently exclude Celtic speaking-people, or treat the Germanic peoples as the name of a people, this new definition, by using Germanic language as the main criterion, understood the Germani as a people or nation (Volk) with a stable group identity linked to language. Some scholars have subsequently gone so far as to treat Roman-era Germanic people as non-Germanic if it seems they spoke Celtic languages.[20] Germanic peoples as "speakers of a Germanic language" are sometimes referred to as "Germanic-speaking peoples".[1]

Apart from the linguistic designation (Germanic languages), the use of the terms "Germanic" and "Germanic peoples/Germani" has become controversial in modern scholarship.[1] Recent work in archaeology and historiography has questioned the fundamental categories behind the notion, namely the existence of stable "peoples/nations" (Völker) as an important element of history and the connection of archaeological assemblages to ethnicity.[21] This has resulted in different disciplines developing different definitions of "Germanic".[1] Some scholars studying the Early Middle Ages now stress the question of whether the Germanic peoples saw themselves as an ethnic unity, while others point to the existence of Germanic languages as a historical fact that can be used to identify Germanic peoples, regardless of whether they saw themselves as "Germanic".[22]

Reacting to these debates, the editors of Germanische Altertumskunde Online stated in 2013 that the term "Germanic" "remains important for linguistics, but is no longer useful for archaeology or history."[23] Historians of the Toronto school such Walter Goffart and Alexander Callander Murray have argued that there is no indication of any Germanic identity in late antiquity, and that most ideas about Germanic culture are taken from far later epochs and projected backwards to antiquity.[24] For such reasons, Goffart argues that the term Germanic should be avoided entirely in favor of "barbarian" except in the linguistic sense,[25] and historians such as Walter Pohl have also called for the term to be avoided or used with careful explanation.[26] Guy Halsall has argued that it is "fundamentally absurd" to assume that Germanic peoples as geographically distant as the Frisians and Goths all shared a mentality and cultural traits, just as much as it would be to assume this between geographically distant modern Romance-speakers such as the Portuguese and Romanians.[27]

Linguists and philologists have generally reacted skeptically to claims that there was no Germanic identity or cultural unity.[28] Nelson Goering has argued on the basis of the spread of Germanic alliterative verse and Germanic heroic legend that we should find a "middle ground between, on the one hand, the assumption of a clear and distinct Germanic 'national' identity [...] and on the other a perhaps overly strong rejection of any possible validity of the term 'Germanic' when applied to poetic and legendary traditions."[29] Some archaeologists have also argued in favor of retaining the term "Germanic" due to its broad recognizability.[30] Archaeologist Heiko Steuer defines his own work on the Germani in geographical terms (covering Germania) rather than in ethnic terms.[2] He nevertheless argues for some sense of shared identity between the Germani, noting the use of a common language, a common runic script, various common objects of material culture such as bracteates and gullgubber (art-objects, amulets, or offerings), and the confrontation with Rome as things that could cause a sense of shared "Germanic" culture.[31] Another possible sign of a perceived difference between the Germanic-speaking peoples and their neighbors is the use of the terms walhaz to refer to Romance or Celtic speakers and Wends for Slavic speakers; these terms are, however, absent in Gothic and only appear in regions where Germanic speakers bordered other peoples.[32]

Classical terminology[]

The first author to describe the Germani as a large category of peoples distinct from the Gauls and Scythians was Julius Caesar, writing around 55 BCE during his governorship of Gaul.[33] Before this time, only a relatively small group of people along the Rhine seem to have been called Germani,[34] and Caesar's division of the Germani from the Celts was not taken up by most writers in Greek.[35] According to Herbert Schutz, although the peoples to the east of the Rhine included Celts and mixed populations, as a political contrivance Caesar defined a population boundary along the Rhine ignoring cultural lines, invented a people and denominated all of them to the east as Germani, grouping them with the unrelated Cimbri and Teutones and giving their lands the name Germania, as opposed to Gallia (Gaul).[14] When defining the Germani ancient authors did not differentiate consistently between a territorial definition ("those living in Germania") and an ethnic definition ("having Germanic ethnic characteristics"), although the two definitions did not always align.[36]

In Caesar's account, the clearest defining characteristic of the Germani people was that they lived east of the Rhine,[37] opposite Gaul on the west side, an observation he made with historical digressions in his writing. Caesar sought to explain both why his legions stopped at the Rhine and also why the Germani were more dangerous than the Gauls and a constant threat to the empire.[38] He also classified the Cimbri and Teutons, peoples who had previously invaded Italy, as Germani, and examples of this threat to Rome.[39][40] Similarly, Caesar classified his own opponents east of the Rhine, most notably the Suebi, as Germanic.[41] Caesar and, following him, the Roman writer Tacitus in his Germania (c. 98 CE), depicted the Germani as sharing elements of a common culture.[42]A small number of passages by Tacitus and other Roman authors (Caesar, Suetonius) mention Germanic tribes or individuals speaking a language distinct from Gaulish. For Tacitus (Germania 43, 45, 46), language was a characteristic, but not defining feature of the Germanic peoples.[43] Much of this description represented them as typically "barbarian", including the possession of stereotypical vices such as "wildness" and of virtues such as chastity.[44] Tacitus was at times unsure whether a people were Germanic or not, expressing his uncertainty about the Bastarnae, who he says looked like Sarmatians but spoke like the Germani, about the Osi and the Cotini, and about the Aesti, who were like Suebi but spoke a different language.[45]

Caesar and authors following him regarded Germania as stretching east of the Rhine for an indeterminate distance, bounded by the Baltic Sea and the Hercynian Forest.[46] Pliny the Elder and Tacitus placed the eastern border at the Vistula.[47] The Upper Danube served as a southern border. Between there and the Vistula Tacitus described an unclear boundary, describing Germania as separated in the south and east from the Dacians and the Sarmatians by mutual fear or mountains (Latin: Germania omnis... a Sarmatis Dacisque mutuo metu aut montibus separatur).[48] This undefined eastern border is related to a lack of stable frontiers in this area such as were maintained by Roman armies along the Rhine and Danube.[35] The geographer Ptolemy (2nd century CE) applied the name Germania magna ("Greater Germania", Greek: Γερμανία Μεγάλη) to this area, contrasting it with the Roman provinces of Germania Prima and Germania Secunda (on the west bank of the Rhine).[49] In modern scholarship, Germania magna is sometimes also called Germania libera ("free Germania"), a name that became popular among German nationalists in the 19th century.[50]

Although Caesar described the Rhine as the border between Germani and Celts, he also describes a group of people he identifies as Germani who live on the west bank of the Rhine in the northeast of Gall, the Germani cisrhenani.[51] It is unclear if these Germani spoke a Germanic language, and they may have been Celtic speakers instead. Some of their names do not have good Celtic or Germanic etymologies, leading to the hypothesis of a third Indo-European language in the area between the rivers Meuse and Rhine.[52] According to Tacitus, it was among this group, specifically the Tungri, that the name Germani first arose, and was spread to further groups.[53] Tacitus continues to mention Germanic tribes on the west bank of the Rhine in the period of the early Empire, such as the Tungri, Nemetes, Ubii, and the Batavi.[54]

The Romans did not regard the eastern Germanic-speakers such as Goths, Gepids, and Vandals as Germani, but rather connected them with other non-Germanic-speaking peoples such as the Huns, Sarmatians, and Alans.[35] Romans described these peoples, including those who did not speak a Germanic language, as "Gothic people" (gentes Gothicae) and most often classified them as "Scythians".[55] The writer Procopius, describing the Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Vandals, Alans, and Gepids, derived the Gothic peoples from the ancient Getae and described them as sharing similar customs, beliefs, and a common language.[56]

Classical subdivisions[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

By the 1st century CE, the writings of Pliny the Elder and Tacitus reported a division of Germanic peoples into large groupings.[57][58] Tacitus, in his Germania, specifically stated that one such division mentioned "in old songs" (carminibus antiquis)[59] derived three such groups (genera) from three sons of Mannus, who was son of an earth-born god called Tuisco.[60][61] (Inspired by this, these three groups are also sometimes used in older modern linguistic terminology, attempting to describe the divisions of later Germanic languages.) Pliny the Elder, believed to be one of the main sources of Tacitus, named two more races of Germani in his Historia Naturalis, with the same basic three groups as Tacitus, plus two more eastern blocks of Germans, the Vandals, and further east the Bastarnae.[62]

- Ingvaeones or Ingævones, nearest to the Ocean according to Tacitus, and including the Cimbri, Teutoni, and Chauci according to Pliny.

- Herminones or Hermiones in the interior, included the Suevi, the Hermunduri, the Chatti, the Cherusci according to Pliny. They had been mentioned in one earlier source, Pomponius Mela, in his slightly earlier source, but in a different more remote location: "the farthest people of Germania, the Hermiones" somewhere to the east of the Cimbri and the Teutones, apparently on the Baltic.[63]

- Istvaeones, the remainder, "join up to the Rhine" according to Pliny, and included the Cimbri - which appears to be an error because they were already listed as Ingvaeones.

- The Vandili, mentioned only by Pliny in this list, are believed to be predecessors of the later Vandals, and their group included the Burgundiones, the Varini, Carini, and Gutones. (The Varini were listed by Tacitus as being Suebic, and the Gutones are described by him as a remote Germanic group.)

- The Peucini, who are also the Basternæ, adjoining the Daci.

On the other hand, Tacitus wrote in the same passage that some believe that there are other groups which are just as old as these three, including "the Marsi, Gambrivii, Suevi, Vandilii". Of these, Tacitus discussed only the Suebi (Suevi) in detail, specifying that they were a very large grouping covering the greater part of Germania, but they were not a single people (gens) but rather many tribes (nationes) with their own names.[64] The largest, he said, was the Semnones near the Elbe, who "claim that they are the oldest and the noblest of the Suebi."[65]

Strabo, who focused mainly on Germani between the Elbe and Rhine, and does not mention the sons of Mannus, also set apart the names of Germani who are not Suevian, in two other groups, similarly implying three main divisions: "smaller German tribes, as the Cherusci, Chatti, Gamabrivi, Chattuarii, and next the ocean the Sicambri, Chaubi, Bructeri, Cimbri, Cauci, Caulci, Campsiani".[66]

These accounts and others from the period emphasize that the Suevi formed an especially large and powerful group. Tacitus speaks also of a geographical "Suebia" with two halves either side of the Sudetes.[67]

Languages[]

Proto-Germanic[]

All Germanic languages derive from the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE), which is generally reckoned to have been spoken between 4500 and 2500 BCE.[68] The ancestor of Germanic languages is referred to as Proto- or Common Germanic,[69] and likely represented a group of mutually intelligible dialects.[70] They share distinctive characteristics which set them apart from other Indo-European sub-families of languages, such as Grimm's and Verner's law, the conservation of the PIE ablaut system in the Germanic verb system (notably in strong verbs), or the merger of the vowels a and o qualities (ə, a, o > a; ā, ō > ō).[71] During the Pre-Germanic linguistic period (2500–500 BCE), the proto-language has almost certainly been influenced by linguistic substrates still noticeable in the Germanic phonology and lexicon.[72][a] Shared grammatical innovations suggest also very early contacts between Germanic and the Indo-European Baltic languages.[75] The leading theory, suggested by archaeological and genetic evidence,[76] postulates a diffusion of Indo-European languages from the Pontic–Caspian steppe towards Northern Europe during the third millennium BCE, via linguistic contacts and migrations from the Corded Ware culture towards modern-day Denmark, resulting in cultural mixing with the indigenous Funnelbeaker culture.[77][b]

Between around 500 BCE and the beginning of the Common Era, archeological and linguistic evidence suggest that the Urheimat ('original homeland') of the Proto-Germanic language, the ancestral idiom of all attested Germanic dialects, was primarily situated in the southern Jutland peninsula, from which Proto-Germanic speakers migrated towards bordering parts of Germany and along the sea-shores of the Baltic and the North Sea, an area corresponding to the extent of the late Jastorf culture.[78][c] One piece of evidence is the presence of early Germanic loanwords in the Finnic and Sámi languages (e.g. Finnic kuningas, from Proto-Germanic *kuningaz 'king'; rengas, from *hringaz 'ring'; etc.),[79] with the older loan layers possibly dating back to an earlier period of intense contacts between pre-Germanic and Finno-Permic (i.e. Finno-Samic) speakers.[80] There is also a great deal of influence in vocabulary from the Celtic languages, but most of this appears to be much later,[81] with most loanwords occurring either before or during the sound shift described by Grimm's Law.[82] Germanic also shows some similarities in vocabulary to the Italic languages, similarities which are often shared with Celtic.[75] An archeological continuity can also be demonstrated between the Jastof culture and populations defined as Germanic by Roman sources.[83]

Although Proto-Germanic is reconstructed without dialects via the comparative method, it is almost certain that it never was a uniform proto-language.[84] The late Jastorf culture occupied so much territory that it is unlikely that Germanic populations spoke a single dialect, and traces of early linguistic varieties have been highlighted by scholars.[85] Sister dialects of Proto-Germanic itself certainly existed, as evidenced by the absence of the First Germanic Sound Shift (Grimm's law) in some "Para-Germanic" recorded proper names, and the reconstructed Proto-Germanic language was only one among several dialects spoken at that time by peoples identified as "Germanic" by Roman sources or archeological data.[83] Although Roman sources name various Germanic tribes such as Suevi, Alemanni, Bauivari, etc., it is unlikely that the members of these tribes all spoke the same dialect.[86]

Early attestations[]

Definite and comprehensive evidence of Germanic lexical units only occurred after Caesar's conquest of Gaul in the 1st century BCE, after which contacts with Proto-Germanic speakers began to intensify. The Alcis, a pair of brother gods worshipped by the Nahanarvali, are given by Tacitus as a Latinized form of *alhiz (a kind of 'stag'), and the word sapo ('hair dye') is certainly borrowed from Proto-Germanic *saipwōn- (English soap), as evidenced by the parallel Finnish loanword saipio.[87] The name of the framea, described by Tacitus as a short spear carried by Germanic warriors, most likely derives from the compound *fram-ij-an- ('forward-going one'), as suggested by comparable semantical structures found in early runes (e.g., raun-ij-az 'tester', on a lancehead) and linguistic cognates attested in the later Old Norse, Old Saxon and Old High German languages: fremja, fremmian and fremmen all meant 'to carry out'.[88]

In the absence of evidence earlier than the 2nd century CE, it must be assumed that Proto-Germanic speakers living in Germania were members of preliterate societies.[90] The only pre-Roman inscriptions that could be interpreted as Proto-Germanic, written in the Etruscan alphabet, have not been found in Germania but rather in the Venetic region. The inscription harikastiteiva\\\ip, engraved on the Negau helmet in the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE, possibly by a Germanic-speaking warrior involved in combat in northern Italy, has been interpreted by some scholars as Harigasti Teiwǣ (*harja-gastiz 'army-guest' + *teiwaz 'god, deity'), which could be an invocation to a war-god or a mark of ownership engraved by its possessor.[89] The inscription Fariarix (*farjōn- 'ferry' + *rīk- 'ruler') carved on tetradrachms found in Bratislava (mid-1st c. BCE) may indicate the Germanic name of a Celtic ruler.[91]

The earliest attested runic inscriptions (Vimose comb, Øvre Stabu spearhead), initially concentrated in modern Denmark and written with the Elder Futhark system, are dated to the second half of the 2nd century CE.[92] Their language, named Primitive Norse, Proto-Norse, or similar terms, and still very close to Proto-Germanic, has been interpreted as a northern variant of the Northwest Germanic dialects and the ancestor of the Old Norse language of the Viking Age (8th–11th c. CE).[93] Based upon its dialect-free character and shared features with West Germanic languages, some scholars have contended that it served as a kind of koiné language in (parts of) the Northwest Germanic area.[94] However, the merging of unstressed Proto-Germanic vowels, attested in runic inscriptions from the 4th and 5th centuries CE, also suggests that Primitive Norse could not have been a direct predecessor of West Germanic dialects.[95]

Longer texts in Germanic languages post-date the Proto-Germanic period. They begin with the Gothic Bible, written in the Gothic alphabet in the 6th century, and then with texts in the Latin alphabet beginning in the 8th century in modern England and shortly thereafter in modern Germany.[96]

Linguistic disintegration[]

By the time Germanic speakers entered written history, their linguistic territory had stretched farther south, since a Germanic dialect continuum (where neighbouring language varieties diverged only slightly between each other, but remote dialects were not necessarily mutually intelligible due to accumulated differences over the distance) covered a region roughly located between the Rhine, the Vistula, the Danube, and southern Scandinavia during the first two centuries of the Common Era.[97] East Germanic speakers dwelled on the Baltic sea coasts and islands, while speakers of the Northwestern dialects occupied territories in present-day Denmark and bordering parts of Germany at the earliest date when they can be identified.[98]

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, migrations of East Germanic gentes from the Baltic Sea coast southeastwards into the hinterland led to their separation from the dialect continuum.[99] By the late 3rd century CE, linguistic divergences like the West Germanic loss of the final consonant -z had already occurred within the "residual" Northwest dialect continuum.[95] The latter definitely ended after the 5th- and 6th-century migrations of Angles, Jutes and part of the Saxon tribes towards modern-day England.[100] In view of the later linguistic situation of modern-day Denmark, populated by North Germanic-speakers, it is assumed that the original dialects of Jutland were assimilated by speakers of a more northerly dialect (Danes) after the Anglo-Saxon migrations, breaking the continuum between Scandinavia and the more southerly Germanic-speaking regions; however, this cannot be shown in the archaeological or historical record.[101][102]

Classification[]

Although they have certainly influenced academic views on ancient Germanic languages up until the 20th century, the traditional groupings given by contemporary authors like Pliny and Tacitus are no longer regarded as reliable by modern linguists, who base their reasoning on the attested sound changes and shared mutations which occurred in geographically distant groups of dialects.[103] The Germanic languages are traditionally divided between East, North and West Germanic branches.[104] The modern prevailing view is that North and West Germanic were also encompassed in a larger subgroup called Northwest Germanic.[105]

- Northwest Germanic: mainly characterized by the i-umlaut, and the shift of the long vowel *ē towards a long *ā in accented syllables;[106] it remained a dialect continuum following the migration of East Germanic speakers in the 2nd–3rd century CE;[107]

- North Germanic or Primitive Norse: initially characterized by the monophthongization of the sound ai to ā (attested from ca. 400 BCE);[108] a uniform northern dialect or koiné attested in runic inscriptions from the 2nd century CE onward,[109] it remained practically unchanged until a transitional period that started in the late 5th century;[110] and Old Norse, a language attested by runic inscriptions written in the Younger Fuþark from the beginning of the Viking Age (8th–9th centuries CE);[111]

- West Germanic: including Old Saxon (attested from the 5th c. CE), Old English (late 5th c.), Old Frisian (6th c.), Frankish (6th c.), Old High German (6th c.), and possibly Langobardic (6th c.), which is only scarcely attested;[112] they are mainly characterized by the loss of the final consonant -z (attested from the late 3rd century),[113] and by the j-consonant gemination (attested from ca. 400 BCE);[94] early inscriptions from the West Germanic areas found on altars where votive offerings were made to the Matronae Vacallinehae (Matrons of Vacallina) in the Rhineland dated to ca. 160−260 CE; West Germanic remained a "residual" dialect continuum until the Anglo-Saxon migrations in the 5th–6th centuries CE;[100]

- East Germanic, of which only Gothic is attested by both runic inscriptions (from the 3rd c. CE) and textual evidence (principally Wulfila's Bible; ca. 350−380). It became extinct after the fall of the Visigothic Kingdom in the early 8th century.[99] The inclusion of the Burgundian and Vandalic languages within the East Germanic group, while plausible, is still uncertain due to their scarce attestation.[114] The latest attested East Germanic language, Crimean Gothic, has been partially recorded in the 16th century.[115]

Further internal classifications are still debated among scholars, as it is unclear whether the internal features shared by several branches are due to early common innovations or to the later diffusion of local dialectal innovations.[116][d] The West Germanic group remains somewhat problematic linguistically, and appears more diverse in the early period than North or East Germanic.[117] Seebold Elmar proposes the existence of an English, Frisian, and Continental group within West Germanic.[118] According to Ludwig Rübekeil, if Old English and Old Frisian certainly share distinctive characteristics such as the Anglo-Frisian nasal spirant law, attested by the 6th century in inscriptions on both sides of the North Sea, and the use of the fuþorc system with additional runes to convey innovative and shared sound changes, it is unclear whether those common features are really inherited or have rather emerged by connections over the North Sea.[119]

The linguist Friedrich Maurer rejected the traditional three-way division of the Germanic languages by breaking up West Germanic and proposed a five-way division, partially following then current archaeological finds, and partially following divisions among the ancient Germanic peoples found in Tacitus. Thus Maurer proposed the existence of Rhine-Weser Germanic (Tacitus's Istvaeones), North Sea Germanic (Tacitus's Ingvaeones), Elbe Germanic (Tacitus's Irminones), (East Germanic), and North Germanic. Although influential, Maurer's thesis failed to replace the older model.[120] Aside from "North Sea Germanic", Maurer's groupings within West Germanic ("Rhine-Weser" "Elbe Germanic") do not hold up to linguistic scrutiny.[121]

Archaeology[]

The pre-Roman Iron Age Jastorf culture (sixth to first centuries BCE), which was located on the North German Plain and in Jutland is associated with Germanic-speaking peoples.[122] Assuming that the Jastorf Culture is the origin of the Germanic peoples, then the Scandinavian peninsula would have become Germanic either via migration or assimilation over the course of the same period.[123] Alternatively, Hermann Ament has stressed that two other archaeological groups must have belonged to the people called Germani by Caesar, one on either side of the Lower Rhine and reaching to the Weser, and another in Jutland and southern Scandinavia. These groups would thus show a "polycentric origin" for the Germanic peoples.[124] The neighboring Przeworsk culture in modern Poland is also taken to be Germanic, while the La Tène culture, found in southern Germany and the modern Czech Republic, is taken to be Celtic.[125] The identification of the Jastorf culture with the Germani has been criticized by Sebastian Brather, who notes that it seems to be missing areas such as southern Scandinavia and the Rhine-Weser area, which linguists argue to have been Germanic, while also not according with the Roman era definition of Germani, which included Celtic-speaking peoples further south and west.[126]

For latter periods, archaeologists, following a terminology developed by the philologist and linguist Friedrich Maurer, divide the Germanic area roughly following Tacitus's divisions of the Germanic peoples, into Rhine-Weser Germanic, North Sea Germanic, Elbe Germanic, and East Germanic. This division does not, however, accurately represent the archaeology of the Germanic area.[127] The distributions of distinct material cultures discovered by archaeologists working in Germania do not correspond to the locations of Germanic tribes as given by Tacitus.[128] New archaeological finds have tended to show that the boundaries between these groups were very permeable, and scholars now assume that migration and the collapse and formation of cultural units were constant occurrences within Germania.[129]

According to Heiko Steuer, archaeology shows that, contrary to the assertion of Roman authors, only about thirty percent of Central Europe was covered with thick forest in Antiquity, about the same percentage as today. Villages were not distant from each other but often within sight, revealing a fairly high population density.[130] Germanic wooden construction was not "primitive", but rather adapted to the local conditions. Although Roman authors claimed that the Germani had no fortresses or temple structures, archaeology has revealed the existence of both. Archaeology also shows that from at least the turn of the 3rd century CE larger regional settlements existed that were not exclusively involved in an agrarian economy, and that the main settlements of the Germani were connected by paved roads. The entirety of Germania was within a system of long-distance trade.[131] Nor was the Germanic economy too primitive to be worth conquering by the Romans; every village seems to have produced its own iron, which sometimes was even exported to Rome, and frequently produced its own salt and lead as well.[130] Steuer argues that Rome failed to conquer Germania after Tiberius not because of the uselessness of such a conquest, but rather because the population was too large and could assemble too many warriors, either as opponents or as foreign auxiliaries for the Roman army.[132]

History[]

The Germanic cultural area appears to have become established in the first millennium BCE with the crystallization of the archaeological Jastorf culture and the Germanic consonantal shift.[133] Generally, scholars agree that it is possible to speak of Germanic-speaking peoples after 500 BCE, although the first attestation of the name "Germani" is not until much later.[134]

Earliest attestations[]

Possible earliest contacts with the classical world (4th–3rd centuries BCE)[]

Before Julius Caesar, Romans and Greeks had very little contact with northern Europe itself. Pytheas, who travelled to Northern Europe some time in the late 4th century BCE, was one of the few sources of information for later historians.[e] The Romans and Greeks however had contact with northerners who came south, but for the cultured Greco-Romans, these "barbarians" were conceived in archetypal terms as being poor, brutish, uncivilized, and ignorant of higher civilization, albeit physically hardened by their rugged lives.[135]

The Bastarnae or Peucini are mentioned in historical sources going back as far as the 3rd century BCE through the 4th century CE.[136] These Bastarnae were described by Greek and Roman authors as living in the territory east of the Carpathian Mountains, and north of the Danube's delta at the Black Sea. They were variously described as Celtic or Scythian, but much later Tacitus, in disagreement with Livy, said they were similar to the Germani in language. According to some authors then, the Bastarnae and Sciri were the first Germani to reach the Greco-Roman world and the Black Sea area.[137]

In 201–202 BCE, the Macedonians, under the leadership of King Philip V, conscripted the Bastarnae as soldiers to fight against the Roman Republic in the Second Macedonian War.[138] They remained a presence in that area until late in the Roman Empire. The Peucini were a part of this people who lived on Peuce Island, at the mouth of the Danube on the Black Sea.[138] King Perseus enlisted the service of the Bastarnae in 171–168 BCE to fight the Third Macedonian War. By 29 BCE, they had been subdued by the Romans and those that remained presumably merged into various groups of Goths into the 2nd century CE.[138]

Another eastern people known from about 200 BCE, and sometimes believed to be Germanic-speaking, are the Sciri (Greek: Skiroi), because they appear in the text of a decree of Olbia, a city on the Black Sea, which records the names of the barbarians who threatened the city, including the Galatians, Sciri, and Scythians (Galatai, Skiroi, and Skythia), among others.[139] There is a theory that the name of the Sciri, perhaps meaning pure, was intended to contrast with that of the Bastarnae, perhaps meaning mixed, or "bastards".[140] Much later, Pliny the Elder placed them to the north near the Vistula together with an otherwise unknown people called the Hirrii.[141] The Hirrii are sometimes equated with the Harii mentioned by Tacitus in this region, whom he considered to be Germanic Lugians. These names have also been compared to that of the Heruli,[citation needed] another eastern Germanic people.[142]

Cimbrian War (2nd century BCE)[]

Late in the 2nd century BCE, Roman and Greek sources recount the migrations of the far northern "Gauls", i.e., the Cimbri, Teutones and Ambrones whom Caesar later classified as Germanic. They first appeared in eastern Europe where some researchers propose they may have been in contact with the Bastarnae and Scordisci. In 113 BCE, they defeated the Boii at the Battle of Noreia in Noricum.[143]

The movements of these groups through parts of Gaul, Italy and Hispania resulted in the Cimbrian War, led primarily by its Consul, Gaius Marius.[144]

In Gaul, a combined force of Cimbri and Teutoni and others defeated the Romans in the Battle of Burdigala (107 BCE) at Bordeaux, in the Battle of Arausio (105) at Orange in France, and in the Battle of Tridentum (102) at Trento in Italy.[145] Their further incursions into Roman Italy were repelled by the Romans at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae (Aix-en-Provence) in 102 BCE, and the Battle of Vercellae in 101 BCE (in Vercelli in Piedmont).[146]

One classical source, Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus, mentions the northern Gauls somewhat later, associating them with eastern Europe, saying that both the Bastarnae and the Cimbri were allies of Mithridates VI.[147]

Germano-Roman contacts[]

Julius Caesar (1st century BCE)[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Caesar campaigned in Gaul (what is now France) from 58 to 50 BCE, in the period of the late Roman Republic.[148] His recording of his exploits during this campaign introduced the term "Germanic" to refer to peoples such as the Cimbri and Suevi.[149]

- 63 BCE Ariovistus, described by Caesar as a Germanic king,[150] led mixed forces over the Rhine into Gaul as an ally of the Sequani and Averni in their battle against the Aedui, who they defeated at the Battle of Magetobriga. He stayed there on the west of the Rhine. He was also accepted as an ally by the Roman senate.

- 58 BCE. Caesar, as governor of Gaul, took the side of the Aedui against Ariovistus and his allies. He reported that Ariovistus had already settled 120,000 of his people, was demanding land for 24,000 Harudes who subsequently defeated the Aedui,[151] and had 100 clans of Suevi coming into Gaul. Caesar defeated Ariovistus at the Battle of Vosges (58 BC).[152]

- 55-53 BCE. Controversially, Caesar moved his attention to Northern Gaul. In 55 BCE he made a show of strength on the Lower Rhine, crossing it with a quickly made bridge, and then massacring a large migrating group of Tencteri and Usipetes who crossed the Rhine from the east.[155] In the winter of 54/53 the Eburones, the largest group of Germani cisrhenani, revolted against the Romans and then dispersed into forests and swamps.

Still in the 1st century BCE the term Germani was used by Strabo (see above) and Cicero in ways clearly influenced by Caesar.[156] Of the peoples encountered by Caesar, the Tribocci, Vangiones, Nemetes and Ubii were all to be found later, on the east of the Rhine, along the new frontier of the Roman empire.

Julio-Claudian dynasty (27 BCE – 68 CE) and the Year of Four Emperors (69 CE)[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

During the reign of Augustus from 27 BCE until 14 CE, the Roman empire became established in Gaul, with the Rhine as a border.[157] From 12 to 9 BCE, the Roman Empire dominated the region between the Rhine and the Weser, and possibly also the region between the Weser and Elbe, creating the short-lived Roman province in Germania.[158] Following the Roman defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE, Rome gave up on the possibility of fully integrating this region into their empire.[159] In the reign of his successor Tiberius it became state policy to expand the empire no further than the frontier based roughly upon the Rhine and Danube. The Julio-Claudian dynasty, the extended family of Augustus, paid close personal attention to management of this Germanic frontier, establishing a tradition followed by many future emperors. Major campaigns were led from the Rhine personally by Nero Claudius Drusus, step-son of Augustus, then by his brother the future emperor Tiberius; next by the son of Drusus, Germanicus (father of the future emperor Caligula and grandfather of Nero).[160]

In 38 BCE, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, consul of Transalpine Gaul, became the second Roman to lead forces over the Rhine.[161] In 31 BCE Gaius Carrinas repulsed an attack by Suevi from east of the Rhine.[162] In 25 BCE Marcus Vinicius took vengeance on some Germani in Germania, who had killed Roman traders.[163] In 17/16 BCE at the Battle of Bibracte the Sugambri, Usipetes, and Tencteri crossed the Rhine and defeated the 5th legion under Marcus Lollius, capturing the legion's eagle.

From 13 BCE until 17 CE there were major Roman campaigns across the Rhine nearly every year, often led by members of the family of Augustus. First came the pacification of the Usipetes, Sicambri, and Frisians near the Rhine, then attacks increased further from the Rhine, on the Chauci, Cherusci, Chatti and Suevi (including the Marcomanni). These campaigns eventually reached and even crossed the Elbe, and in 5 CE Tiberius was able to show strength by having a Roman fleet enter the Elbe and meet the legions in the heart of Germania. However, within this period two Germanic kings formed large anti-Roman alliances. Both of them had spent some of their youth in Rome:

- After 9 BCE, Maroboduus of the Marcomanni had led his people away from the Roman activities into the Bohemian area, which was defended by forests and mountains, and formed alliances with other peoples. Tacitus referred to him as king of the Suevians.[164] In 6 CE Rome planned an attack but forces were needed for the Illyrian revolt in the Balkans, until 9 CE, at which time another problem arose in the north...

- In 9 CE, Arminius of the Cherusci, initially an ally of Rome, drew the a large unsuspecting Roman force into a trap in northern Germany, and defeated Publius Quinctilius Varus at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Tiberius and Germanicus spent the next few years recovering their dominance of northern Germany. They made Maroboduus an ally, and he did not assist Arminius.

- 17-18 CE, war broke out between Arminius and Maroboduus, with indecisive results.

- 19 CE, Maroboduus was deposed by a rival claimant, perhaps supported by the Romans, and fled to Italy. He died in 37 CE. Germanicus also died, in Antioch.

- 21 CE. Arminius died, murdered by opponents within his own group.

Strabo, writing in this period in Greek, mentioned that apart from the area near the Rhine itself, the areas to the east were now inhabited by the Suevi, "who are also named Germans, but are superior both in power and number to the others, whom they drove out, and who have now taken refuge on this side the Rhine". Various peoples had fallen "prey to the flames of war".[165]

The Julio-Claudian dynasty also recruited northern Germanic warriors, particularly men of the Batavi, as personal bodyguards to the Roman emperor,[166] forming the so-called Numerus Batavorum. After the end of the dynasty in 68 CE with the suicide of the emperor Nero, the Germanic bodyguard (custodes corporis) were dissolved by Galba in the same year[167] because he suspected they were loyal to the old dynasty.[168] The decision caused deep offense to the Batavi, and contributed to the outbreak of the Revolt of the Batavi in the following year which united Germani and Gauls, all connected to Rome but living both within the empire and outside it, over the Rhine.[169] Their indirect successors were the Equites singulares Augusti which were, likewise, mainly recruited from the Germani. They were apparently so similar to the Julio-Claudians' earlier German Bodyguard that they were given the same nickname, the "Batavi".[170] Gaius Julius Civilis, a Roman military officer of Batavian origin, orchestrated the Revolt. The revolt lasted nearly a year and was ultimately unsuccessful.[171]

Flavian and Antonine dynasties (70–192 CE)[]

The Emperor Domitian of the Flavian dynasty faced attacks from the Chatti in Germania superior, with its capital at Mainz, a large group which had not been in the alliance of Arminius or Maroboduus. The Romans claimed victory by 84 CE, and Domitian also improved the frontier defenses of Roman Germania, consolidating control of the Agri Decumates, and converting Germania Inferior and Germania Superior into normal Roman provinces. In 89 CE the Chatti were allies of Lucius Antonius Saturninus in his failed revolt.[172][173] Domitian, and his eventual successor Trajan, also faced increasing concerns about an alliance on the Danube of the Suevian Marcomanni and Quadi, with the neighbouring Sarmatian Iazyges; it was in this area that dramatic events unfolded over the next few generations. Trajan himself expanded the empire in this region, taking over Dacia. Between 162 and 163, the Chatti once again attacked the Roman provinces of Raetia (with its capital at Augsburg) and Germania Superior.[174]

Up until their confrontation, the Marcomanni and Quadi lived in amicitia (friendship/alliance) with the Empire.[175] However, Emperor Domitian attacked them as punishment for not aiding him against the Dacians. Then, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, a dispute arose between Rome and the Quadi concerning the installation of a new king and by 166, the tensions became a conflict when a group of allied Langobardi and Orbii invaded Pannonia.[175] Thus began the Marcomannic Wars, which were prosecuted by Aurelius; a series of conflicts with a related chronology that is "difficult to reconstruct" according to historian Walter Pohl, even when one takes into consideration the treasures found, the related legends, inscriptions, and the reliefs of the Marcus Column.[176] By 168 (during the Antonine plague), barbarian hosts consisting of Marcomanni, Quadi, and Sarmatian Iazyges, attacked and pushed their way to Italy.[177] They advanced as far as Upper Italy, destroyed Opitergium/Oderzo and besieged Aquileia. Eventually, the Roman armies were able to push the barbarians back, but it was not until 178/179 that the Emperor succeeded in forcing the Marcomanni and Quadi north of the Danube and got the situation under control.[176]

By 180 CE, the Marcommanic Wars were finally brought to a conclusion.[178] Dio Cassius called it the war against the Germani, noting that Germani was the term used for people who dwell up in those parts (in the north).[g] A large number of peoples from north of the Danube were involved, not all Germanic-speaking, and there is much speculation about what events or plans led to this situation. Many scholars believe causative pressure was being created by aggressive movements of peoples further north, for example with the apparent expansion of the Wielbark culture of the Vistula, probably representing Gothic peoples who may have pressured Vandal peoples towards the Danube.[179]

Other peoples, perhaps not all of them Germanic, were involved in various actions—these included the Costoboci, the Hasdingi and Lacringi Vandals, the Varisci (or Naristi) and the Cotini (who Tacitus claimed spoke Gallic, which "proves that they are not Germans"),[180] and possibly also the Buri.[181]

After these Marcomannic wars, the Middle Danube began to change, and in the next century the peoples living there generally tended to be referred to as Gothic by the Romans, rather than Germanic, at least for those living north of the Black Sea.[182]

New names on the frontiers (170–370)[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

By the early 3rd century AD, large new groupings of Germanic people appeared near the Roman frontier, though they were not strongly unified. The first of these conglomerations mentioned in the historical sources were the Alamanni (a term meaning "all men") who appear in Roman texts sometime in the 3rd century CE.[183] These are believed to have been a mixture of mainly Suevian peoples, who coalesced in the Agri Decumates. Emperor Severus Alexander was killed by his own soldiers in 235 CE for paying for peace with the Alamanni, following which the anti-aristocratic general Maximinus Thrax was elected to be emperor by the Pannonian army.[184] According to the notoriously unreliable Augustan History (Historia Augusta), he was born in Thrace or Moesia to a Gothic father and an Alanic mother,[185]

Secondly, soon after the appearance of the Alamanni on the Upper Rhine, the Franks began to be mentioned as occupying the land at the bend of the lower Rhine. In this case, the collective name was new, but the original peoples who composed the group were largely local, and their old names were still mentioned occasionally. The Franks were still sometimes called Germani as well.

Thirdly, the Goths and other "Gothic peoples" from the area of today's Poland and Ukraine, many of whom were Germanic-speaking peoples, began to appear in records of this period.

- In 238, Goths crossed the Danube and invaded Histria. The Romans made an agreement with them, giving them payment and receiving prisoners in exchange.[186] The Dacian Carpi, who had been paid off by the Romans before then, complained to the Romans that they were more powerful than the Goths.[187][188]

- After his victory in 244, Persian ruler Shapur I recorded his defeat of the Germanic and Gothic soldiers who were fighting for emperor Gordian III. Possibly this recruitment resulted from the agreements made after Histria.[186]

- After attacks by the Carpi into imperial territory in 246 and 248, Philip the Arab defeated them and then cut off payments to the Goths.[188] In 250 CE a Gothic king Cniva led Goths with Bastarnae, Carpi, Vandals, and Taifali into the empire, laying siege to Philippopolis. He followed his victory there with another on the marshy terrain at Abrittus, a battle which cost the life of Roman emperor Decius.[186]

- In 253/254, further attacks occurred reaching Thessalonica and possibly Thrace.[189]

- In approximately 255-257 there were several raids from the Black sea coast by "Scythian" peoples, apparently first led by the Boranes, who were probably a Sarmatian people.[190] These were followed by bigger raids led by the Herules in 267/268, and a mixed group of Goths and Herules in 269/270.

In 260 CE, as the Roman Imperial Crisis of the Third Century reached its climax, Postumus, a Germanic soldier in Roman service, established the Gallic Empire, which claimed suzerainty over Germania, Gaul, Hispania and Britannia. Postumus was eventually assassinated by his own followers, after which the Gallic Empire quickly disintegrated.[191] The traditional types of border battles with Germani, Sarmatians and Goths continued on the Rhine and Danube frontiers after this.

- In the 270s the emperor Probus fought several Germanic peoples who breached territory on both the Rhine and the Danube, and tried to maintain Roman control over the Agri Decumates. He fought not only the Franks and Alamanni, but also Vandal and Burgundian groups now apparently near the Danube.

- In the 280s, Carus fought Quadi and Sarmatians.

- In 291, the 11th panegyric praising emperor Maximian was given in Trier; this marked the first time the Gepids, Tervingi and Taifali were mentioned. The passage described a battle outside the empire where the Gepids were fighting on the side of the Vandals, who had been attacked by Taifali and a "part" of the Goths. The other part of the Goths had defeated the Burgundians who were supported by Tervingi and Alemanni.[192]

In the 350s Julian campaigned against the Alamanni and Franks on the Rhine. One result was that Julian accepted that the Salian Franks could live within the empire, north of Tongeren.

By 369, the Romans appear to have ceded their large province of Dacia to the Tervingi, Taifals and Victohali.[189]

Migration Period (ca. 375–568)[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Since its very beginning, the Roman empire had proactively kept the northern peoples and the potential danger they represented under control, just as Caesar had proposed. However, the ability to handle the barbarians in the old way broke down in the late 4th century and the western part of the empire itself broke down. In addition to the Franks on the Rhine frontier, and Suevian peoples such as the Alamanni, a sudden movement of eastern Germanic-speaking "Gothic peoples" now played an increasing role both inside and outside imperial territory.

Gothic entry into the empire[]

The Gothic wars of the late 4th century saw a rapid series of major events: the entry of a large number of Goths in 376; the defeat of a major Roman army and killing of emperor Valens at the Battle of Adrianopolis in 378; and a subsequent major settlement treaty for the Goths which seems to have allowed them significant concessions compared to traditional treaties with barbarian peoples. While the eastern empire eventually recovered, the subsequent long-reigning western emperor Honorius (reigned 393–423) was unable to impose imperial authority over much of the empire for most of his reign.[193] In contrast to the eastern empire, in the west the "attempts of its ruling class to use the Roman-barbarian kings to preserve the res publica failed".[194]

The Gothic wars were affected indirectly by the arrival of the nomadic Huns from Central Asia in the Ukrainian region. Some Gothic peoples, such as the Gepids and the Greuthungi (sometimes seen as predecessors of the later Ostrogoths), joined the newly forming Hunnish faction, and played a prominent role in the Hunnic Empire, where Gothic became a lingua franca.[195] Based on the description of Socrates Scholasticus, Guy Halsall has argued that the Hunnish hegemony developed after a major campaign by Valens against the Goths, which had caused great damage, but failed to achieve a decisive victory.[196] Peter Heather has argued that Socrates should be rejected on this point, as inconsistent with the testimony of Ammianus.[197]

The Gothic Thervingi, under the leadership of Athanaric, had in any case borne the impact of the campaign of Valens, and were also losers against the Huns, but clients of Rome. A new faction under leadership of Fritigern, a Christian, were given asylum inside the Roman Empire in 376 CE. They crossed the Danube and became foederati.[198] With the emperor occupied in the Middle East, the Tervingi were treated badly and becoming desperate; significant numbers of mounted Greuthungi, Alans and others were able to cross the river and support a Tervingian uprising leading to the massive Roman defeat at Adrianople.[199]

Around 382, the Romans and the Goths now within the empire came to agreements about the terms under which the Goths should live. There is debate over the exact nature of such agreements, and for example whether they allowed the continuous semi-independent existence of pre-existing peoples; however the Goths do appear to have been allowed more privileges than in traditional settlements with such outside groups.[200] One result of the comprehensive settlement was that the imperial army now had a larger number of Goths, including Gothic generals.[201]

Imperial turmoil[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

By 383 a new emperor, Theodosius I, was seen as victorious over the Goths and having brought the situation back under control. Goths were a prominent but resented part of the eastern military. The Greutungi and Alans had been settled in Pannonia by the western co-emperor Gratian (assassinated in 383) who was himself a Pannonian. Theodosius died 395, and was succeeded by his sons: Arcadius in the east, and Honorius, who was still a minor, in the west. The Western empire had however become destabilized since 383, with several young emperors including Gratian having previously been murdered. Court factions and military leaders in the east and west attempted to control the situation.

Alaric was a Roman military commander of Gothic background, who first appears in the record in the time of Theodosius. After the death of Theodosius, he became one of the various Roman competitors for influence and power in the difficult situation. The forces he led were described as mixed barbarian forces, and clearly included many other people of Gothic background, a phenomenon which had become common in the Balkans. In an important turning point for Roman history, during the factional turmoil, his army came to act increasingly as an independent political entity within the Roman empire, and at some point he came to be referred to as their king, probably around 401 CE, when he lost his official Roman title.[202] This is the origin of the Visigoths, whom the empire later allowed to settle in what is now southwestern France. While military units had often had their own ethnic history and symbolism, this is the first time that such a group established a new kingdom. There is disagreement about whether Alaric or his family had a royal background, but there is no doubt that this kingdom was a new entity, very different from any previous Gothic kingdoms.

Invasions of 401–411[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

In the aftermath of the large-scale Gothic entries into the empire, the Germanic Rhine peoples, the Franks and Alemanni, became more secure in their positions in 395, when Stilicho made agreements with them; these treaties allowed him to withdraw the imperial forces from the Rhine frontier in order to use them in his conflicts with Alaric and the Eastern empire.[203]

The reasons that these invasions apparently all dispersed from the same area, the Middle Danube, are uncertain. It is most often argued that the Huns must have already started moving west, and consequently pressuring the Middle Danube. Peter Heather for example writes that around 400, "a highly explosive situation was building up in the Middle Danube, as Goths, Vandals, Alans and other refugees from the Huns moved west of the Carpathians" into the area of modern Hungary on the Roman frontier.[204]

Whatever the chain of events, the Middle Danube later became the centre of Attila's loose empire containing many East Germanic people from the east, who remained there after the death of Attila. The makeup of peoples in that area, previously the home of the Germanic Marcomanni, Quadi and non-Germanic Iazyges, changed completely in ways which had a significant impact on the Roman empire and its European neighbours. Thereafter, though the new peoples ruling this area still included Germanic-speakers, as discussed above, they were not described by Romans as Germani, but rather "Gothic peoples".

- In 401, Claudian mentions a Roman victory over a large force including Vandals, in the province of Raëtia. It is possible that this group was involved in the later crossing of the Rhine.[205]

- In 405–406, Radagaisus, who was probably Gothic, entered the empire on the Middle Danube with a very large force of unclearly defined, but apparently Gothic, composition, and invaded Italy.[206] He was captured and killed in 406 near Florence and 12000 of his men recruited into Roman forces.

- A more successful invasion, apparently also originating from the Middle Danube, reached the Rhine a few months later. As described by Halsall: "On 31 December 405 a huge body from the interior of Germania crossed the Rhine: Siling and Hasding Vandals, Sueves and Alans. [...] The Franks in the area fought back furiously and even killed the Vandal king. Significantly no source mentions any defense by Roman troops."[207] The composition of this group of barbarians, who were not all Germanic-speaking, indicates that they had traveled from the area north of the Middle Danube. (The Suevians involved may well have included remnants of the once powerful Marcomanni and Quadi.) The non-Germanic Alans were the largest group, and one part of them under King Goar settled with Roman acquiescence in Gaul, while the rest of these peoples entered Roman Iberia in 409 and established kingdoms there, with some travelling further to establish the Vandal kingdom of North Africa.

- In 411 a Burgundian group established themselves in northern Germania Superior on the Rhine, between Frankish and Alamanni groups, holding the cities of Worms, Speyer, and Strassburg. They and a group of Alans helped establish yet another short-lived claimant to the throne, Jovinus, who was eventually defeated by the Visigoths cooperating with Honorius.

Motivated by the ensuing chaos in Gaul, in 406 the Roman army in Britain elected Constantine "III" as emperor and they took control there.

In 408, the eastern emperor Arcadius died, leaving a child as successor, and the west Roman military leader Stilicho was killed. Alaric, wanting a formal Roman command but unable to negotiate one, invaded Rome itself, twice, in 401 and 408.

Constantius III, who became Magister militum by 411, restored order step-by-step, eventually allowing the Visigoths to settle within the empire in southwest Gaul. He also committed to retaking control of Iberia, from the Rhine-crossing groups. When Constantius died in 421, having been co-emperor himself for one year, Honorius was the only emperor in the West. However, Honorius died in 423 without an heir. After this, the Western Roman empire steadily lost control of its provinces.

From Western Roman Empire to medieval kingdoms (420–568)[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

The Western Roman Empire declined gradually in the 5th and 6th centuries, and the eastern emperors had only limited control over events in Italy and the western empire. Germanic speakers, who by now dominated the Roman military in Europe, and lived both inside and outside the empire, played many roles in this complex dynamic. Notably, as the old territory of the western empire came to be ruled on a regional basis, the barbarian military forces, ruled now by kings, took over administration with differing levels of success. With some exceptions, such as the Alans and Bretons, most of these new political entities identified themselves with a Germanic-speaking heritage.

In the 420s, Flavius Aëtius was a general who successfully used Hunnish forces on several occasions, fighting Roman factions and various barbarians including Goths and Franks.[208][209] In 429 he was elevated to the rank of magister militum in the western empire, which eventually allowed him to gain control of much of its policy by 433.[210] One of his first conflicts was with Boniface, a rebellious governor of the province of Africa in modern Tunisia and Libya. Both sides sought an alliance with the Vandals based in southern Spain who had acquired a fleet there. In this context, the Vandal and Alan kingdom of North Africa and the western Mediterranean would come into being.[211][212]

- In 433 Aëtius was in exile and spent time in the Hunnish domain.

- In 434, the Vandals were granted the control of some parts of northwest Africa, but Aëtius defeated Boniface using Hunnish forces.

- In 436 Aëtius defeated the Burgundians on the Rhine with the help of Hunnish forces.[213]

- In 439 the Vandals and their allies captured Carthage. The Romans made a new agreement recognizing the Visigothic kingdom.

- In 440, the Hunnish "empire" as it could now be called, under Attila and his brother Bleda began a series of attacks over the Danube into the eastern empire, and the Danubian part of the western empire. They received enormous payments from the eastern empire and then focused their attentions to the west, where they were already familiar with the situation, and in friendly contact with the African Vandals.

- In 442 Aëtius seems to have granted the Alans who had remained in Gaul a kingdom, apparently including Orléans, possibly to counter local independent Roman groups (so called Bagaudae, who also competed for power in Iberia).

- In 443 Aëtius settled the Burgundians from the Rhine deeper in the empire, in Savoy in Gaul.

- In 451, the large mixed force of Attila crossed the Rhine but was defeated by Aetius with forces from the settled barbarians in Gaul: Visigoths, Franks, Burgundians and Alans.

- In 452 Attila attacked Italy, but had to retreat to the Middle Danube because of an outbreak of disease.

- In 453, Aëtius and Attila both died.

- In 454, the Hunnish alliance divided and the Huns fought the Battle of Nedao against their former Germanic vassals. The names of the peoples who had made up the empire appear in records again. Several of them were allowed to become federates of the eastern empire in the Balkans, and others created kingdoms in the Middle Danube.

In the subsequent decades, the Franks and Alamanni tended to remain in small kingdoms but these began to extend deeper into the empire. In northern Gaul, a Roman military "King of Franks" also seems to have existed, Childeric I, whose successor Clovis I established dominance of the smaller kingdoms of the Franks and Alamanni, whom they defeated at the Battle of Zülpich in 496.

Compared to Gaul, what happened in Roman Britain, which was similarly both isolated from Italy and heavily Romanized, is less clearly recorded. However the result was similar, with a Germanic-speaking military class, the Anglo-Saxons, taking over administration of what remained of Roman society, and conflict between an unknown number of regional powers. While major parts of Gaul and Britain redefined themselves ethnically on the basis of their new rulers, as Francia and England, in England the main population also became Germanic-speaking. The exact reasons for the difference are uncertain, but significant levels of migration played a role.[214][215]

In 476 Odoacer, a Roman soldier who came from the peoples of the Middle Danube in the aftermath of the Battle of Nedao, became King of Italy, removing the last of the western emperors from power. He was murdered and replaced in 493 by Theoderic the Great, described as King of the Ostrogoths, one of the most powerful Middle Danube peoples of the old Hun alliance. Theoderic had been raised up and supported by the eastern emperors, and his administration continued a sophisticated Roman administration, in cooperation with the traditional Roman senatorial class.[216] Similarly, culturally Roman lifestyles continued in North Africa under the Vandals, in Savoy under the Burgundians, and within the Visigothic realm.

The Ostrogothic kingdom ended in 542 when the eastern emperor Justinian made a last great effort to reconquer the Western Mediterranean. The conflicts destroyed the Italian senatorial class,[217] and the eastern empire was also unable to hold Italy for long. In 568 the Lombard king Alboin, a Suevian people who had entered the Middle Danubian region from the north conquering and partly absorbing the frontier peoples there, entered Italy and created the Italian Kingdom of the Lombards there. These Lombards now included Suevi, Heruli, Gepids, Bavarians, Bulgars, Avars, Saxons, Goths, and Thuringians. As Peter Heather has written these "peoples" were no longer peoples in any traditional sense.[218]

Older accounts which describe a long period of massive movements of peoples and military invasions are oversimplified, and describe only specific incidents. According to Herwig Wolfram, the Germanic peoples did not and could not "conquer the more advanced Roman world" nor were they able to "restore it as a political and economic entity"; instead, he asserts that the empire's "universalism" was replaced by "tribal particularism" which gave way to "regional patriotism".[219] The Germanic peoples who overran the Western Roman Empire probably numbered less than 100,000 people per group, including approximately 15,000-20,000 warriors. They constituted a tiny minority of the population in the lands over which they seized control.[220]

Apart from the common history many of them had in the Roman military, and on Roman frontiers, a new and longer-term unifying factor for the new kingdoms was that by 500, the start of the Middle Ages, most of the old Western empire had converted to the same Rome-centred Catholic form of Christianity. A key turning point was the conversion of Clovis I in 508. Before this point, many of the Germanic kingdoms, such as those of the Goths and Burgundians, now adhered to Arian Christianity, a form of Christianity which they perhaps took up in the time of the Arian emperor Valens, but which was now considered a heresy.

Early Middle Ages[]

The transition of the Migration period to the Middle Ages proper took place over the course of the second half of the 1st millennium. It was marked by the Christianization of the Germanic peoples and the formation of stable kingdoms replacing the mostly tribal structures of the Migration period. Some of this stability is discernible in the fact that the Pope recognized Theodoric's reign when the Germanic conqueror entered Rome in CE 500, despite that Theodoric was a known practitioner of Arianism, a faith which the First Council of Nicaea condemned in CE 325.[221] Theodoric's Germanic subjects and administrators from the Roman Catholic Church cooperated in serving him, helping establish a codified system of laws and ordinances which facilitated the integration of the Gothic peoples into a burgeoning empire, solidifying their place as they appropriated a Roman identity of sorts.[222] The foundations laid by the Empire enabled the successor Germanic kingdoms to maintain a familiar structure and their success can be seen as part of the lasting triumph of Rome.[223]

In continental Europe, this Germanic evolution saw the rise of Francia in the Merovingian period under the rule of Clovis I who had deposed the last emperor of Gaul, eclipsing lesser kingdoms such as Alemannia.[224] The Merovingians controlled most of Gaul under Clovis, who, through conversion to Christianity, allied himself with the Gallo-Romans. While the Merovingians were checked by the armies of the Ostrogoth Theodoric, they remained the most powerful kingdom in Western Europe and the intermixing of their people with the Romans through marriage rendered the Frankish people less a Germanic tribe and more a "European people" in a manner of speaking.[225] Most of Gaul was under Merovingian control as was part of Italy and their overlordship extended into Germany where they reigned over the Thuringians, Alamans, and Bavarians.[226] Evidence also exists that they may have even had suzerainty over south-east England.[227] Frankish historian Gregory of Tours relates that Clovis converted to Christianity partly as a result of his wife's urging and even more so due to having won a desperate battle after calling out to Christ. According to Gregory, this conversion was sincere but it also proved politically expedient as Clovis used his new faith as a means to consolidate his political power by Christianizing his army.[228][h] Against Germanic tradition, each of the four sons of Clovis attempted to secure power in different cities but their inability to prove themselves on the battlefield and intrigue against one another led the Visigoths back to electing their leadership.[229]

When Merovingian rule eventually weakened, they were supplanted by another powerful Frankish family, the Carolingians, a dynastic order which produced Charles Martel, and Charlemagne.[230] The coronation of Charlemagne as emperor by Pope Leo III in Rome on Christmas Day, CE 800 represented a shift in the power structure from the south to the north. Frankish power ultimately laid the foundations for the modern nations of Germany and France.[231] For historians, Charlemagne's appearance in the historical chronicle of Europe also marks a transition where the voice of the north appears in its own vernacular thanks to the spread of Christianity, after which the northerners began writing in Latin, Germanic, and Celtic; whereas before, the Germanic people were only known through Roman or Greek sources.[232]

In England, the Germanic Anglo-Saxon tribes reigned over the south of Great Britain from approximately 519 to the 10th century until the Wessex hegemony became the nucleus for the unification of England.[233][234]

Scandinavia was in the Vendel period and eventually entered the Viking Age, with expansion to Britain, Ireland and Iceland in the west and as far as Russia and Greece in the east.[235][236][237] Swedish Vikings, known locally as the Rus', had ventured deep into Russia, where they founded the state of Kievan Rus'. In cooperation with Crimean Goths, the Rus' destroyed the Khazar Khaganate and became the dominant power in Eastern Europe. They were eventually assimilated by the local East Slavic population.[238] By CE 900 the Vikings secured for themselves a foothold on Frankish soil along the Lower Seine River valley in what is now France that became known as Normandy. Hence they became the Normans. They established the Duchy of Normandy, a territorial acquisition which provided them the opportunity to expand beyond Normandy into Anglo-Saxon England.[239]

The various Germanic tribal cultures began their transformation into the larger nations of later history, English, Norse and German, and in the case of Burgundy, Lombardy and Normandy blending into a Romano-Germanic culture. Many of these later nation states started originally as "client buffer states" for the Roman Empire so as to protect it from its enemies further away.[240] Eventually they carved out their own unique historical paths.

Religion[]

Germanic paganism[]

Like their neighbors and other historically related peoples, the ancient Germanic peoples venerated numerous indigenous deities. These deities are attested throughout literature authored by or written about Germanic-speaking peoples, including runic inscriptions, contemporary written accounts, and in folklore after Christianization. As an example, the second of the two Merseburg charms (two Old High German examples of alliterative verse from a manuscript dated to the ninth century) mentions six deities: Woden, Balder, Sinthgunt, Sunna, Frija, and Volla.[241]

With the exception of Sinthgunt, cognates to these deities occur in other Germanic languages, such as Old English and Old Norse. By way of the comparative method, philologists are then able to reconstruct and propose early Germanic forms of these names from early Germanic mythology. Compare the following table:

| Old High German | Old Norse | Old English | Proto-Germanic reconstruction | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wuotan[242] | Óðinn[242] | Wōden[242] | *Wōđanaz[242] | A deity similarly associated with healing magic in the Old English Nine Herbs Charm and particular forms of magic throughout the Old Norse record. This deity is strongly associated with extensions of *Frijjō (see below). |

| Balder[243] | Baldr[243] | Bældæg[243] | *Balđraz[243] | In Old Norse texts, where the only description of the deity occurs, Baldr is a son of the god Odin and is associated with beauty and light. |

| Sunne[244] | Sól[244] | Sigel[244] | *Sowelō ~ *Sōel[245][246] | A theonym identical to the proper noun 'Sun'. A goddess and the personified Sun. |

| Volla[247] | Fulla[247] | Unattested | *Fullōn[247] | A goddess associated with extensions of the goddess *Frijjō (see below). The Old Norse record refers to Fulla as a servant of the goddess Frigg, while the second Merseburg Charm refers to Volla as Friia's sister. |

| Friia[248] | Frigg[248] | Frīg[248] | *Frijjō[248] | Associated with the goddess Volla/Fulla in both the Old High German and Old Norse records, this goddess is also strongly associated with the god Odin (see above) in both the Old Norse and Langobardic records. |