Cultural impact of Madonna

Since the beginning of her career in the early 1980s, American singer and songwriter Madonna has had a social-cultural impact on the world through her recordings, attitude, clothing and lifestyle. Over the course of her career, Madonna has been described by multiple international authors as the "greatest" woman in music or arguably the most "influential" female recording artist. She also attained the status of "cultural icon" as was noted by cultural theorist Stuart Sim.

Madonna has built a legacy that goes beyond music and has been studied by sociologists, historians and other social scientists,[1][2][3] encompassed in a large part from Madonna studies. Her musical influence has been compared with that of older and long-established icons like Elvis Presley and The Beatles. In terms of record sales, Madonna is regarded as the best-selling woman in music history recognized by Guinness World Records. Many critics have retrospectively credited her presence, success and contributions with paving the way for female artists and changing the music scene for women in music, most notorious for pop and dance stages. Reviews of her work have also served "as a roadmap for scrutinizing women at each stage in their music career".[4]

According to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Madonna is the first multimedia pop icon in history. Frenchman scholar Georges Claude Guilbert felt she has a greater cultural importance and proposes her as a postmodern myth, that has apparent universality and timelessness. Academic Camille Paglia called her a "major historical figure". References to Madonna in popular culture are found in the arts, literature, the music and even science. In a general sense, journalist Peter Robinson noted that "Madonna invented contemporary pop fame so there is a little bit of her in the DNA of every modern pop thing."[5]

She is also a polarizing figure. During her career, Madonna has attracted contradictory cultural social attention from family organizations, feminist anti-porn and religious groups worldwide with boycott and protests.

General overview[]

She's a major historical figure and when she passes, the retrospectives will loom larger and larger in history because right now we just see the present Madonna and it's, like, cringe-making.

—Academic Camille Paglia on Madonna (2017) in a feminist perspective.[6]

Multiple academics and authors have noted Madonna's cultural impact since she appeared on the scene in the 1980s and have commented her continued influence and legacy in the following decades. In the late-2010s, musicologist Eduardo Viñuela of University of Oviedo in a conversation with Radio France Internationale commented that "analyzing Madonna" is to delve into the evolution of many of the most relevant aspects of society in recent decades.[7]

Madonna was suggested by Ann Powers of The New York Times in 1998 as a "secular goddess, designated by her audience and pundits alike as the human face of social change".[8] Around this time, some academics described her as "a barometer of culture that directs the attention to cultural shifts, struggles and changes".[9] British author George Pendle writing for Bidoun explained that she defined a way of living in the 1980s and 1990s and this led to consistently described her as a "cultural icon".[10] In 2002, British academic researcher Brian McNair proposed that "Madonna more than made up for in iconic status and cultural influence".[11]

Canadian professor Karlene Faith gave her point of view saying that Madonna's peculiarity is that "she has cruised so freely through so many cultural terrains" and she "has been a 'cult figure' within self-propelling subcultures just as she became a major".[12] Within the compedium The Madonna companion: two decades of commentary, American poet Jane Miller proposes that "Madonna functions as an archetype directly inside contemporary culture" and she compared its with the Black Virgin.[13] In the description of American author Strawberry Saroyan, Madonna is a "storyteller" and a "cultural pioneer". She stated: "Madonna's ability to take her message beyond music and impact women's lives has been her legacy".[14] Romanian professor Doru Pop at Babeș-Bolyai University described in his book The Age of Promiscuity (2018) that Madonna is an "amalgamated cultural icon" and noted that she was once suggested by other authors like professor John Izod, as a "hero of our times".[15] Professors and authors of Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World, Volume 1 (2011), described:

Madonna's cultural influence has been profound and pervasive, as her multiple transformations and controversies have attracted the attention of numerous scholars working in a variety of fields, namely feminist and queer theory, cultural studies, film and media studies. Scholarly debates about Madonna encompass a broad of spectrum of topics [...] Critical studies of Madonna reveal her—as symbol, image, and brand—[16]

Commentaries about Madonna's cultural influence or legacy can be also found in traditional newspapers and other media outlets. In this line, Janice Min of Billboard declared in 2016 that "Madonna is one of a miniscule number of super-artists whose influence and career transcended music".[1] In further retrospect views, The Cut editor Rebecca Harrington paraphrasing said "Madonna's actual accomplishments are too much for the modern human to even contemplate".[17] William Langley from The Daily Telegraph feels that "Madonna has changed the world's social history, has done more things as more different people than anyone else is ever likely to."[18] Contributor from company Spin Media concluded that "Madonna has changed society through her fiery ambition and unwillingness to compromise".[19] Marissa G. Muller from W remarked that "Madonna has left her mark on every facet of culture".[20]

In United States[]

Madonna has been called an "American icon". Both her early impact and legacy in the culture of United States have been noted either by Americans or international authors. Academics in American Icons (2006) felt that like Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley or Coca-Cola, Madonna image "is immediately recognizable around the world and instantly communicates many of the values of U.S. culture".[21] A gender consultant and musicologist in a course dedicated to Madonna at the University of Oviedo in 2015, proposes that her history and evolution is "comparable" and can be "useful to analyze the historical development of the United States".[22] Argentine essayist and writer, Rodrigo Fresán viewed her as one of the "classic symbols of Made in USA".[23] Another external perception came from French academic Georges Claude Guilbert whose expressed (c. 2002) that "today, America knows more about Madonna than about any passage of the Bible".[24] American editor Annalee Newitz stated that the singer has given to American culture, and culture throughout the world, "is not a collection of songs; rather, it is a collection of images".[2] As a self-made case, U.S. cultural historian and author Jim Cullen wrote that "few figures in American life have managed to exert as much control over their destinies as she has, and the fact that she has done so as a woman is all the more remarkable". Cullen also expressed "that Madonna has done this is indisputable".[25]

Professor Beretta E. Smith-Shomade felt that only Madonna rivaled the space Oprah Winfrey occupied in the late twentieth century and in the psyche of national culture.[26] In 20th century American society, she was referenced by her sexual feminist political movement. Ann Powers summarized that "intellectuals described her as embodying sex, capitalism and celebrity itself".[8] Retrospectively, Sara Marcus described with the height of her career, "the singer brought the changes to American culture". Marcus felt "her revelatory spreading of sexual liberation to Middle America, changed this country for the better. And that's not old news; we're still living it" and also ends saying that Madonna "remade American culture".[27] Historian professor Glen Jeansonne gives his point saying that she "freed Americans from their inhibitions and made them feel good about having fun".[28] For Scottish author Andrew O'Hagan "Madonna is like a heroic opponent of cultural and political authoritarianism of the American "establishment".[29]

Madonna as an icon[]

Marcel Danesi, a professor of semiotics and linguistic anthropology at the University of Toronto cited in Language, Society, and New Media: Sociolinguistics that the word "icon" is a "term of religious origin and used for the first time in celebrity culture to describe the American pop singer Madonna".[30] Following description asserts that the word "is now used in reference to any widely known celebrity, male or female".[30] Some dictionaries around the world such as Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary and the Diccionario panhispánico de dudas included her name to illustrate the new meaning of that word.[31][32]

Madonna has been called an "icon" in many fields where she received a great treatment of analysis such as feminist, sexual, queer or gender studies largely derived from the Madonna studies. Associate professor Diane Pecknold documented in American Icons (2006) that "the fact that not only her work but her person was open to multiple interpretations contributed to the rise of Madonna studies".[33] Also, Rolling Stone staff commented that "she is a living icon not just for her contrivances" but she "as idea, example, archetype exits simultaneously with the real woman".[34]

Feminism[]

Madonna as a feminist icon has generated variety of opinions worldwide over the decades. Canadian commentator Mark Steyn explained that "she has her feminist significance pondered by college courses" and named her a "metaphor for the industry".[35] Richard Appignanesi and Chris Garratt wrote in Introducing Postmodernism: A Graphic Guide (2014) that for some "Madonna is the cyber-model of the New Woman".[36] In 2012, activist and writer Jennifer Baumgardner felt that Madonna "gave birth to 'femme-inism'".[37] Professor Sut Jhally said that the singer "is as an almost sacred feminist icon".[38] In 1990, academic Camille Paglia called Madonna a "true feminist" and labeled as "the future of feminism".[39] Retrospectively, Paglia asserted in 2017 that "it happened".[6]

In 2011, The Guardian included Madonna in its "Top 100 women" list, with editor Homa Khaleeli declaring "no matter the decade or the fashion, she has always been frank about her toughness and ambition". She further added that Madonna "inspires not because she gives other women a helping hand, but because she breaks the boundaries of what's considered acceptable for women".[40] In 2012, Spanish cultural critic Víctor Lenore convened a researchers panel discussion her as a feminist icon.[41] One of the comments, included that "she democratized the idea of women as protagonists and as agents of their own action", while some ambiguous ones stated that she contributed to women's empowerment of a few Western women, straight and gay middle class, but that empowerment is not feminism, because it is individualistic.[41] For others, such as feminist Australian commentator Melinda Tankard Reist, "Madonna has turned her back on the cause of women" and also advised in her 2016 article she has been described as "threat to the status quo".[42]

Sex symbol[]

Madonna has been referred to as a sexual icon, and sex symbol.[26][43] Some references such as American Masters suggested that Madonna's continued to be a sexual icon as "she's gotten older".[44] Sexual connotation has been a part of her career, while Courtney E. Smith in the book Record Collecting for Girls (2011) documented that most people associate Madonna with sex.[45] Essayist Chuck Klosterman in Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs (2003) commented that "whenever I hear intellectuals talk about sexual icons of the present day, the name mentioned most is Madonna".[46] About those widely perceptions, physicist Stephen Hawking once joked: "I have sold more books on physics than Madonna has on sex".[47]

Madonna's usage of her sexuality since the start of her career was documented and highlighted by some for being part of a musical scene generally dominated by male. Professor Santiago Fouz-Hernandez and author of Madonna's Drowned Worlds (2004) wrote that Madonna "emerged as a role model for women in many different cultures, symbolizing professional and personal independence in a male-dominated society, as well as sexual liberation".[48] Among contemporary views, her sexuality was perceived by biographers Wendy Leigh and Stephen Karten noting that she "dominated and manipulated any man within her reach" while scholars Shari Benstock and Suzanne Ferriss also commented that "boys are toys for her".[49][50] This perception shared by many, was commented by psychiatrist and author Jule Eisenbud whose stated Madonna's refusal to accept that power and femininity "is equivalent to masculinity" and "has allowed her to maintain her status as a sex symbol".[51] Academics and authors continued revisiting her sexuality in the following decades, and Dr. Susan Hopkins in her book Girl Heroes: The New Force in Popular Culture (2002) viewed a Madonna at 43 saying that she "is ageing before the world" but she keeps presenting herself as a kind of "sexual revolutionary".[52] Freya Jarman, a music scholar at the University of Liverpool told in 2018 that Madonna "was now demonstrating a new kind of relevance" and emphasized that "as an aging, female popular musician who is still so much in the public eye, she is absolutely relevant".[53]

Among reassessments in regards both her impact and legacy, American editor Janice Min confirmed that "Madonna owned her sexuality" and further explained that "she made people cringe but also think differently about female performers" and viewed "her role as a provocateur changed boundaries for ensuing generations".[54] However, some like Jewish rabbi Shmuley Boteach criticized Madonna, expressing: "Before Madonna, it was possible for women more famous for their voices than their cleavage[,] to emerge as music superstars" and ends saying that in "the post-Madonna universe" many artists "now feel the pressure to expose their bodies on national television to sell albums".[55] In further comments culture columnist Robin Meltzer for New Statesman assured that the singer "irrevocably changed the media image of female sexuality".[56] Jaime Anderson taught at the European School of Management and Technology that she is one of the world's first performers to "manipulate the juxtaposition of sexual and religious themes".[57]

Fashion and image[]

Musicologist Susan McClary wrote that "great deal of ink has been spilled in the debate over Madonna's visual image".[59] British professor and linguist Sara Mills in her book Gendering the Reader (1994) noted that "academic writing on Madonna has seen her as innovative largely in her use of images, and has concentrated overwhelmingly on her video work".[60] Two decades later, writing for The Journal of Popular Culture in 2014, associate professor Jose F. Blanco confirmed that academics and fashion critics have commented Madonna's influence in fashion.[61]

Blanco further add his view on Madonna in this terrain saying that she uses clothes as a "cultural signifier to communicate her persona du jour" as well "she is the creator of numerous personae".[61] Professors in Oh Fashion (1994) wrote that "fashion and identity for Madonna are inseparable from her aesthetic practices" including several cultural interventions from her cultivation of her image such as her music videos, films, TV appearances or concerts.[62] Sabrina Barr of The Independent noted reviews by academic Douglas Kellner on Madonna's fashion and identity usage with her clothes and she emphasized "that way in which the singer used her style to represent her identity was a fresh concept when she first came into the music scene".[63]

From the start of her career, Madonna has been noted for her constantly image and style changes, while Australian scholar McKenzie Wark assured that alongside David Bowie both "raised this to a fine art".[64] New Zealand fashion academic Vicki Karaminas and Australian lecturer and artist, Adam Geczy authors of Queer Style (2013), explained: She "transmogrified from virgin to dominatrix to Über Fran, each time achieving iconic status". They also asserted that Madonna is "the first woman to do so-and with mainstream panache and approbation".[65]

Her influence in the fashion scene was appreciated by author and teacher Diane Asitimbay whose declared that "Madonna changed fashion forever when she brought bras out [and] wore them publicly".[66] Asistimbay further suggested that Madonna and Michael Jordan "did more for the fashion industry in the United States than many of our fashion models put together".[66] British author and historian Michael Pye felt that the singer "not only makes fashion, she is fashion".[67] As Anna Wintour, editor-in-chief of fashion magazine Vogue also declared: She "makes fashion happen" and stated that "Madonna has been one of the most potent style setters of our time".[67] Under Wintour's control, Madonna became the first celebrity (or non-model) to be pictured on the cover of Vogue.[68] She was recognized by Time as one of the Top 100 icons of all time in fashion, style and design in 2012.[69]

Queer and gay[]

Associate professor Judith A. Peraino proposes that "no one has worked harder to be a gay icon than Madonna, and she has done so by using every possible taboo sexual in her videos, performances, and interviews".[70] Scholars Carmine Sarracino and Kevin Scott in The Porning of America (2008), wrote that the singer "gained particular popularity with gay audiences, signaling the creation of a career-long fan base that would lead to her being hailed as the biggest gay icon of all time".[71] Her impact was also remarked by numerous LGBT publications and organizations with The Advocate naming Madonna "the greatest gay icon".[72] Out magazine pondered that she "positioned herself to be a gay icon before it was cool to be one".[73] President and CEO of organization GLAAD, Sarah Kate Ellis stated in 2019 that Madonna "always has and always will be the LGBTQ community's greatest ally".[74]

Madonna is also referred to as a queer icon and icon of queerness. Theologian Robert Goss expressed: "For me, Madonna has been not only a queer icon but also a Christ icon who has dissolved the boundaries between queer culture and queer faith communities".[75] Musicologist Sheila Whiteley wrote in her book Sexing the Groove: Popular Music and Gender (2013) that "Madonna came closer to any other contemporary celebrity in being an above-ground queer icon".[76]

Postmodernism[]

According to Lucy O'Brien "much has been made of Madonna as a postmodern icon".[77] Madonna is suggested by assistant professor Olivier Sécardin of Utrecht University to epitomise postmodernism.[78] Christian writer Graham Cray gives his point of view saying that "Madonna is perhaps the most visible example of what is called post-modernism",[79] while for Martin Amis she is "perhaps the most postmodern personage on the planet".[79] However, academics Sudhir Venkatesh and Fuat Firat deemed her as "representative of postmodern rebellion".[78] Senior lecturers Stéphanie Genz and Benjamin Brabon in Postfeminism: Cultural Texts and Theories (2009) felt that "whether it is as a woman, mother, pop icon or fifty year old, the American singer challenges our preconceptions of who 'Madonna' is and, more broadly, what these identity categories mean within a postmodern context".[80]

Music[]

The history of pop music can essentially be divided into two eras: pre-Madonna and post-Madonna

—Staff of Billboard on Madonna (2018).[81]

Categorized as a musical icon,[83] her contributions on music has been appreciated by multiple critics, which have also been known to induce controversy.

Diverse authors and music critics such as Roger Blackwell and Stephen Thomas Erlewine credited her as the "first female" to have complete control of her music and image.[54][84][85] Ana Laglere, an editor of Batanga Media explained that before Madonna, record labels determined every step of artists but she introduced her style and conceptually directed every part of her career.[3] Associate professor Carol Benson alongside Allen Metz commented that Madonna entered the music business with definite ideas about her image, but "it was her track record that enabled her to increase her level of creative control over her music".[86] Many years after, she founded Maverick Records and was recognized by Spin as the most successful "vanity label". While under Madonna's control it generated well over $1 billion for Warner Bros. Records, more money than any other recording artist's record label at that time.[87]

Multiple international critics and media outlets felt in retrospect that Madonna's presence is defined for "changing" or "revolutionize" contemporary music history for women's, mainly dance and pop scene.[19][88][89][90][91] While reasons given varies, related-unrelated illustrative commentaries in the point of view of international media include Deutsche Welle, as they documented her as "the first woman to dominate the male world of pop".[92] Further explanations came from sources such as The Times: "Madonna, whether you like her or not, started a revolution amongst women in music".[93] Similarly Joe Levy, Blender editor-in-chief said that she "opened the door for what women could achieve and were permitted to do".[54] In the perception of actress and activist, Susan Sarandon: "The history of women in popular music can, pretty much, be divided into before and after Madonna".[94] Billboard staff also recognized that "the history of pop music can essentially be divided into two eras: pre-Madonna and post-Madonna".[81] Furthermore, Marissa Muller from W felt that she "normalized the idea that pop stars could and should write their own songs".[20]

She has been also discussed with euphemism by various international authors and media outlets as the most "greatest" female artist or arguably the most "influential" in music history.[95][96][97][98] Ben Kelly writing for The Independent gave his thoughts saying that she has "ensured her legacy as the greatest female artist of all time".[97] British musicologist David Nicholls also suggested: "Madonna became the most successful woman in music history by skillfully evoking, inflecting, and exploiting the tensions implicit in a variety of stereotypes and images of women".[99]

Madonna in the contemporary arts[]

Madonna's impact includes her influence on the art world and "has been made almost entirely behind the scenes" according to Stephanie Eckardt from the publication W.[101] Both her contributions and reception in this area can be found in diverse examples. She donated money, contributed or sponsored to various art exhibitions with positive reviews among art critics, including the first major retrospective of Tina Modotti which curator and art historian, Anne d'Harnoncourt commented that "introduces the artist to a broader public".[102] Similar feelings came from Rosie Millard, BBC art correspondent, when she presented the Turner Prize at Tate Britain in 2001.[103] She also sponsored Untitled Film Stills by Cindy Sherman at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1997.[104] As an art collector her possessions are estimated at worth $100 million according to website Artnet,[105] which include over 300 pieces of artists such as Salvador Dali and Frida Kahlo.[106] She appeared in the 100 biggest collectors (c. 1996) by Art & Antiques,[107] and in the Top 25 Art Collectors by The Hollywood Reporter in 2013.[106]

Art critics and art historians such as John A. Walker have also reviewed her career in the perspective of the arts.[108] Aside her related-activities in the art scene, Madonna's notorious involved presence in the process of her work since her early career with video-makers, designers and fashion photographers as well her relationships with plastic artists such as Andy Warhol, Keith Haring and her former boyfriend Jean-Michel Basquiat have been positively remarked.[108][101][109] Within this context, The Irish Times mentioned that Madonna "was the first female pop star to fully engage with the visual elements of her art" while they highlighted her collaborations.[109] A contributor from W said that the singer was "the first to make collaborations between pop artists and designers routine".[20] Curator and photographic critic Vince Aletti focused the attention in his area noting that "the photographic image has been at the forefront of Madonna's rise to iconic status".[110]

As a female performer, she was noted by a W magazine contributor to "pioneering" the crossover between pop and art.[101] She is credited by others as "the first female artist to exploit fully the potential of the music video", a statement included in her profile at Encyclopædia Britannica written by Lucy O'Brien.[111] In the terrain of the video as an art form, film critic Armond White proposes that her concepts led some artists have "art-consciousness" and felt that "they'll never repeat the moment when Madonna's connection to the zeitgeist became historic".[112]

Her art and artistic persona has been also commented by authors which pondered her cultural significance. In the perception of graffiti artist and cultural commentator, Fab Five Freddy "she is the perfect example of the visual artist".[113] Following Michael Jackson's death, a panel of Argentines art critics deemed her as "the only universal artist left standing". Those critics, including Daniel Molina, Graciela Speranza and Alicia de Arteaga explained that she is herself "a multimedia expression that condenses fashion, dance, photography, sculpture, music, video and painting".[114] A similar perception was noted back in the 1990s by Jon Pareles when he invited audience to see her as a "continuous multi-media art project".[115] Writing for Interview in 2014, American artist and illusionist David Blaine described that perhaps Madonna "is herself her own greatest work of art—something so vastly influential as to be unfathomable".[116] Professor John R. May of English and religious studies concludes that the singer is a contemporary "gesamtkunstwerk",[117] and Scottish music writer Alan McGee proposes that she is "post-modern art, the likes of which we will never see again".[118]

Commercial influence[]

Madonna's semiotic and influence also extended to business schools sphere and marketing community. More than one economist, marketer, entrepreneur or other business expert made analysis or dedicated courses to her studying her "success" and commercial "strategies" with academic Douglas Kellner saying that "one cannot fully grasp the Madonna phenomenon without analyzing her marketing strategies".[120]

Economist and scholar Robert M. Grant dedicated a class on her in 2008 highlighting the context of "intensely competitive" and "volatile world of entertainment".[121] Marketer expert and professor Stephen Brown from University of Ulster named her a "marketing genius" while studied her case.[122] Business professor Oren Harari coined the expression "Madonna effect" inspired in her business tactics and changes while deems its use for both individuals and organizations.[123] Doctor Peter van Ham writing for NATO Review explained the "Madonna-curve", an expression used by some business analysts to describe the "adapting to new tasks whilst staying true to one's own principles". He further explained that "businesses use Madonna as a role model of self-reinvention".[124] Athlete turned science writer, Christopher Bergland writing for Psychology Today in 2013 analyzed her success from the perspective of neuroscience.[125]

She also received appreciation from a varied of industry experts in her role as a businesswoman and some of them named her "America's smartest businesswoman".[126] Kelley School of Business said that she is more than a "pop cult icon" and has been "an empire from day one".[127] Professor Robert Miklitsch described that "[she] is herself a corporation and a rather diverse one at that" in his book From Hegel to Madonna (1998) where he talks from the perspectives of the political economy and commodity fetishism.[128] Colin Barrow a visiting scholar at the Cranfield School of Management viewed her as "an organisation unto herself".[126] Writing for London Business School, Martin Kupp an expert in entrepreneurship alongside organizational theorist, Jamie Anderson concluded that she "is a born entrepreneur".[129] In 2018, Patricia Lippe Davis writing for business magazine Campaign also discussed Madonna at 60 while suggested her case as a good example for marketers focusing in older demographics groups of women.[130]

Her contributions in helping to shape music business was appreciated by Lucy O'Brien whose said that Madonna became the first one "to exploit the idea" of pop artist as a brand in the 1980s.[131] Editor Gerald Marzorati proposes that "Madonna's contribution has been to usher in the phenomenon of star as multimedia impresario".[132]

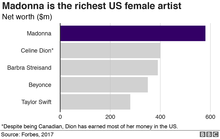

In the 20th and 21st centuries, Guinness World Records have referred to her as "the most successful female artist".[133] The same or similar description has been used in academic fields. A summary of this point could be found from scholars writing for Journal of Business Research in 2020, when they concluded that "she's probably the most successful female music artist ever in terms of her record sales, tour receipts, brand recognition and longevity".[78] In 2015, gender consultant and musicologist Laura Viñuela taught in a course dedicated to Madonna at University of Oviedo that "is the only woman who has such a long and massively successful career in the world of music".[22] Madonna became the first woman entrepreneur to appear on a Forbes cover according to themselves.[134] In addition, she has been included in several of their earnings and fortune lists since her early career in the 1980s and once named the richest woman in music.[135][136] American business magazine, Fast Company discussed her in a 2015 article as "the biggest pop brand on the planet".[137]

Cultural trends[]

- Nota bene: This section only include illustrative examples

In most part of her career, the relationship with Madonna and trends attracted commentaries from multiple observers, including media commentaries and academics alike. Canadian assistant professor Ken McLeod of University of Toronto, confirmed in his book We Are the Champions (2011) that "she has played a part in several cultural trends".[139] Art historian John A. Walker deemed her as an "acute observer of trends" (in terrains such as art or film) and professor Mary Cross observed as well her "appropriation of cultural trends".[140][141] However, lecturer Susan Hopkins from University of Southern Queensland writing for The Conversation in 2016, said that Madonna "pioneered a lot of cultural trends that didn't do average working women a lot of favour".[142]

In a general sense, over the course of her career Madonna has been reported or cited as a help or motivation for the rise, introduction or populary of several things such as terms, places, cultural practices, fashion trends or products with MuchMusic deemed her as "the world's top trend-maker" (c. 2006).[143] Some illustrative credits or related examples include:

Manuel Heredia, minister of tourism in Belize, discussed with El Heraldo de México how "La Isla Bonita" has helped to attract tourists to the San Pedro Town.[144] A similar example occurred when she moved to Lisbon around 2017, and Portuguese or Spanish outlets credited her presence as a boost and help for the tourism industry within sectors such as "luxury tourism" or real estate business.[145][146] Numerous sources such as The Independent credited Madonna to popularise the Jewish mysticism in the Western world.[147] American novelist and former educator Alison Strobel commented that "Madonna had popularized it to the point where it was simple to find a place to go learn".[148] The New York Times (NYT) contributors concluded she "brought" yoga to the masses.[149] The same perception of NYT is shared by others, while professors Isabel Dyck and Pamela Moss particularly credited her the popularity of Ashtanga Yoga.[150] She is also credited in popularising voguing. MFA Stephen Ursprung from Smith College felt that "Madonna created a market for voguing" and further asserted "voguing has left its mark on the world" through a "close connection" with the singer.[151] Danish lecturer Henrik Vejlgaard, also commented both her song and video made "voguing a popular dance concept in many parts of the world".[152]

Professors in American Icons (2006) commented she helped to popularize words and phrases in the English lexicon. They included the term "wannabe" used by Time magazine back in 1985 to describe the Madonna wannabe phenomenon. Another inclusion was the title of her first feature film Desperately Seeking Susan which produced a new idiomatic phrase considering the newspaper headlines.[153] Her position in the raise of idiomatic term fauxmosexual was noted by Kristin Lieb of BuzzFeed News whose remarked in 2018 that this phenomenon started with her kissing both Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera at the 2003 MTV Video Music Awards.[154] The "Madonna-Britney influence" in this term was early mentioned by MedicineNet in 2004.[155]

Academic Juliana Tzvetkova noted that Dolce & Gabbana "received their first international recognition thanks" to Madonna,[156] while journalists such as Lynn Hirschberg wrote that the attention around fashion designer Olivier Theyskens was intensified thanks to the singer.[157] The Daily Telegraph explained that Madonna helped transform Frida Kahlo into a collector's darling.[158] Another commentary came from Mexican art magazine Artes de México whose staff notated in 1991 the importance of Madonna for the "Fridomania".[159] Scholars Rhonda Hammer and Douglas Kellner felt that the phenomenon of femininity inspired by South Asia as a tendency in Western media could go back to February 1998 when Madonna released her video for "Frozen". They wrote that "although Madonna did not initiate the Indian fashion accessories beauty [...] she did propel it into the public eye by attracting the attention of the worldwide media".[160] She has carried the burlesque to mass culture according to Latin critics.[41]

As is cited that MTV helped her, some writers like Mark Bego stated that Madonna helped make MTV (alongside Michael Jackson).[161] Music critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine said that she had a "huge role in popularizing dance music".[162] In another illustrative example, she has credit for the introduction of electronic music to the stage of popular music.[163] Authors such as Lucy O'Brien give credit to Madonna in innovating rave culture (mainly in the 1990s).[164][165] According to the company The Vinyl Factory, her single "Vogue" popularized the usage of Korg M1.[166]

Madonna in popular culture[]

Madonna as a pop icon and figure on popular culture has generated numerous analysis across her career. She is the first multimedia figure in popular culture according to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[167] In the 1990s, academic Douglas Kellner deemed her as "a highly influential pop culture icon" and "the most discussed female singer in popular music".[168] The continued perception of Madonna as a topic in popular culture was expressed by media consultants and scholars of Media Studies: The Essential Resource (2013): "Madonna continues to be a challenging presence within popular culture".[169]

In 2012, Latin critics such as Víctor Lenore perceived Madonna as the most influential presence of popular culture at that time.[41] In 2015, a scholar from program "Research in the Disciplines" of Rutgers University said that "Madonna has become the world's biggest and most socially significant pop icon, as well as the most controversial".[170] When she turned 60 years old in 2018, The Guardian presented a serie of articles discussing her figure in the point of views of multiple authors, including columnists or musicians. Within these comments, The Observer columnist Barbara Ellen notes that "she wanted to define the zeitgeist, not merely reflect it" and defined that "popular culture still reeks of her influence". In her article, it was also notated as "pop's greatest survivor".[171]

Frenchman Georges Claude Guilbert noted that long-time accepted as a pop icon proposes her as a postmodern myth that has apparent "universality" and "timelessness".[24] Also, Russell Iliffe from PRS for Music wrote that "during her career, Madonna has transcended the term 'pop star' to become a global cultural icon".[172]

Public and media figure[]

Authors in academic compendium The Madonna Connection found that "other scholars analyze media-Madonna discourses and representations".[173] In the late-1980s, John Fiske, a media scholar and cultural theorist perceived Madonna as a "site of meanings" for performance purposes.[10] Professor Ann Cvetkovich remarked that figures such as Madonna, reveals the "global reach of media culture".[174] Various academics also noted a commentary from The Village Voice editor Steven Anderson on Madonna, whose said in 1989: "She's become a repository for all our ideas about fame, money, sex, feminism, pop culture, even death". In a retroactively view of this point, British reader Deborah Jermyn of Roehampton University commented in 2016 that Madonna "does age and rather than retire from view Madonna continues to function as a repository".[175]

In the perception of Spanish philosopher, Ana Marta González Madonna doesn't have a "cultural" prominence but proposes in her 2009 essay that with her media appearances the singer "would be more culturally significant than most of the people who have changed the course of history".[176] Around 1993, author David Tetzlaff commented that her "omnipresent" appeal "has to do with hyperreality, but an infinite accumulation of simulacra, an overabundance of information".[177] More than two decades later, music writer and teacher T. Cole Rachel writing for Pitchfork in 2015 commented that "if you aren't a super fan—or even a fan at all—there's no escaping Madonna. She is everywhere".[178] In addition to having been perceived as "omnipresent" by different outlets and for different reasons, other sources felt that beyond music industry she is one of the most "recognizable names in the world".[167][179][57]

She has elicited a number of public perceptions regarding her personality and media manipulation during a part of her career. Music critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine wrote for her profile in Allmusic and MTV that "one of Madonna's greatest achievements is how she has manipulated the media and the public with her music, her videos, her publicity, and her sexuality".[84] Becky Johnston from Interview magazine commented: "[F]ew public figures are such wizards at manipulating the press and cultivating publicity as Madonna is. She has always been a great tease with journalists, brash and outspoken when the occasion demanded it".[180] In more approaches political activist, Jasmina Tešanović called Madonna as "one of the most honest performers in pop culture" and further asserted that her changes "are well-calculated".[181] In 2013, lecturer Becca Cragin said that "Madonna has managed to hold the public's attention for 30 years" with skills such as "expressing herself".[181] Music editor Bill Friskics-Warren wrote that "Madonna's megastardom and cultural ubiquity had made her as much a social construct" and a "person-turned-idea".[182]

"Many different kinds of people[,] appreciate Madonna for many different reasons. Madonna has zealous fans who are young and old, straight and gay, educated and unschooled, First and Third World, black, white, brown, and yellow, and of every sexual preference, demografic category, and lifestyle imaginable. People who differ from one another in every way can all still find something relevant in Madonna's multidimensional, multimediated public imagery.

— Social scientist James Lull (2000)[183]

Fame[]

Stan Hawkins from University of Leeds said that Madonna was the first female solo artist to gain superstar status in the 1980s.[184] Historian Gil Troy confirmed Madonna as "the 1980's dominant female star".[185] A point of contrast is that her popularity declined in the 1990s according to academic Lynn Spigel while Andrew Ferguson argued that her "real crime" had been longevity.[186] Overseas, British author Mark Watts writing for academic journal New Theatre Quarterly in 1996, felt that the rise and (perceived) decline of Madonna has gone, so to say, hand-in-hand with that of postmodern theory — "but none the less pervasively influential for that".[187]

Beyond divided perceptions, Erin Skarda wrote for Time in 2012 that "she essentially redefined what it meant to be famous in America".[69] British author Peter Robinson also proposes that "Madonna pretty much invented contemporary pop fame so there is a little bit of her in the DNA of every modern pop thing".[5] Also, at one time editor Annalee Newitz notated in the 1990s that the "fields of theology to queer studies have written literally volumes about what Madonna's stardom means for gender relations, for American culture and for the future".[2]

Madonna has been slightly described as "the most famous women" or "the most famous female artist" (other relative titles applies) by numerous international media outlets during four consecutive decades.[188] In an intellectual response of this point, French academic Georges Claude Guilbert documented that "in the American, British, Australian and French press" (his four principal sources) "it is generally taken for granted that Madonna is the most famous female in the world".[24] In similar approaches, British scholar and economist Robert M. Grant described her as "the best known woman on the planet" in a class about her in 2008.[121] More context and similar perceptions were provided by multiple authors, with political advisor Aaron Klein commenting in 2007 that she is probably "the most well-known American celebrity in the Middle East".[189] When she was living in the United Kingdom Rosie Millard from BBC described her as "arguably the most famous persona currently residing in the UK".[103] British author Matt Cain summarized in 2018: "she's one of the most famous women ever to have lived".[190] According to Orlando Sentinel, Cornell University ranked Madonna in 2014 as the "most influential woman in history" based in a study of Wikipedia algorithms.[191] Furthermore, financial adviser Alvin Hall placed Madonna in 2003 as the "world's most powerful celebrity" at that time.[192]

Honorific nicknames for Madonna[]

Madonna has been called many things.[193] In regards her titles, honorific nicknames and epithets, Chilean magazine Qué Pasa stated in 1996 that "to Madonna can be attributed many titles and never be exaggerated. She is the undisputed Queen of Pop, sex goddess, and of course marketing".[194] Australian professor Robert Clarke of University of Tasmania wrote in Celebrity Colonialism (2009) that Madonna is identified with a "range of nicknames such as 'The Material Girl' or 'The Queen of Pop' referring to her big business pop career".[195] Scottish music writer Alan McGee asserted that Madonna and Michael Jackson invented the terms "Queen and King of Pop",[118] while American journalist Edna Gundersen described Michael Jackson, Prince and Madonna as a "durable pop triumvirate" in their half-centenary in 2009.[54]

In academic fields of the 1990s, she was referred to as a "modern Medusa" and by some as the "queen of gender disorder" and "racial deconstruction".[9] She was also named "Queen of appropriation".[36] Discussing her then 30-year career in 2013, professor Mathew Donahue which lectures about Madonna in many of his classes at the Department of Popular Culture of Bowling Green State University called her "Queen of all Media".[181] British press dubbed her "Madge" when she moved to London in the late-1990s.[196] She was also referred to as the Queen of MTV and CNN commented that MTV could stand for "Madonna Television".[197][198]

Madonna's influence on other performers[]

Influences for Madonna[]

The National Geographic Society found that historians or anthropologists trace "her influences" from several cultural inspirations such as the Middle Eastern spirituality to feminist art history.[199] She has been also inspired by other performers and celebrities, while many biographers documented that her main inspirations came from the world of arts and cinema, instead music.[200][201] Observers commented her influence she had from other performers with Howard Kramer, curatorial director of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum saying that "although Madonna had her influences, she created her own unmistakable style". He added that the singer "wrote her own ticket; she didn't have to follow anybody's formula".[202]

Madonna's influence[]

"Madonna's influence reigns supreme on today's artists, her impact on pop culture through film and fashion may never be topped, and Madonna changed the role of women in pop music. She gave women power, the ability to do more than just record dance hits, and brought about change in the industry that gave birth to every single pop star today."

—Culture columnist Art Tavana writing for company Spin Media (2014).[19]

A large number of international authors and music journalists have noted and commented Madonna's influence on others, mainly amongst female artists. MTV contributor Jocelyn Vena said that "she's influenced others" and "even herself".[203] Reviewing her then 20-year career in 2003, Ian Youngs from BBC wrote that "her influence on others has come as much from her image as her music". Both Youngs and Paul Rees from Q noted that Madonna "is aware of the influence she has" on others.[204] Continuing with the international media attention of her influence on female artists, authors such as Ann Powers from NPR Music,[205] or newspapers such la Repubblica from Italy have called and lumped many of these musicians as "the heirs of Madonna" or her "musical daughters".[206] This treatment have generated the creation of listicles from diverse sources, including a 2013 ranking by MTV Latin American with the intention to find her "heir".[207]

Music journalist Diego A. Manrique writing for the Portuguese version of El País in 2014, noted the dominance on record charts of her "heirs" noting that in "terms of pop culture" we are living in a "Madonna era".[208] Essayist Gillian Branstetter writing for The Daily Dot also shared similar thoughts and found a greater significance commenting that one of the "biggest factors in this influence" is the context in which Madonna thrived when she appeared in the 1980s where "the vast majority of the top artists in the world were men". Branstetter felt that the singer "is scattered through every major act" and her influence is "almost smothering in its totality".[209] Sources and authors such as Branstetter are aware of the influence of other contemporaries artists beyond Madonna,[209] while i-D contribuitor Nick Levine explained in 2018 that "she didn't set the template alone" but further explained that "more than anyone else, Madonna created the rules of engagement now followed by everyone".[210] The same year, 2018, Billboard staff compared her to Michael Jackson and Prince adding that "Madonna is still the one who most set the template for what a pop star could and should be".[81]

In a larger overview, Michelle Castillo from Time summarized in 2010 that "every pop star (of the past two or three decades) has Madonna to thank in some part for his or her success".[211] Similar thoughts came from professor Mary Cross whose wrote that "new pop icons owe Madonna a debt of thanks" adding that her "influence is undeniable and far reaching".[212] Tony Sclafani writing for MSNBC in 2008, explained what he calls Madonna's impact and effect on the future direction of music after she emerged saying that "artists still use her ideas and seem modern and edgy doing so".[88] Madonna's widespread influence on female artists and the impact she have had in their literature was noted by a contributor from Vice whose said: "Reviews of her work have served as a roadmap for scrutinizing women at each stage in their music career".[4]

Outside the music industry, Madonna has been the subject of numerous books, essays and other literary works while more than a writer cited her as an influence. Writer Maura Johnston gave contex of this point saying that "the appetite for books on Madonna is large, and the variety of approaches writers, editors, and photographers have taken to craft their portraits is a testament to how her career has both inspired and provoked".[213] Examples include Italian writer Francesco Falconi whose reported that she inspired his writing career.[214] Photographer Mario Testino is another example. In an interview with Nigel Farndale he commented Madonna is the first non-model in collaborating with him and credited: "With her I knew I had discovered my style because I like to believe what I am photographing".[215] Fashion designer Anna Sui cited Madonna as an influence in her career. She commented that an encounter with the singer gave her "confidence" and "boosted" the idea to start her first own runway show.[216]

Her influence has been also found in contemporary artists. A general example include a 2014 article from Dazed by curator Jefferson Hack when she was "interpreted by contemporary artists" with portraits in art forms and their feelings about Madonna. One of them was Silvia Prada whose said: "For me, Madonna has became even more important than any art movement in terms of history and popular culture".[217] Scottish painter Peter Howson whose dedicated numerous pieces to the singer once commented that "she's a subject everyone is drawn to".[218] Mexican painter Alberto Gironella dedicated almost all his works in his latest days to Madonna and he described that "more than pop [she] is the last surrealist".[219]

"Madonna" as a nickname or title for others[]

Since the 1980s diverse artists (mainly female musicians) around the world have been called a "Madonna" by the press, critics or intellectuals. That treatment has also received significant coverage in the literature of some of them. Taking Britney Spears as example, Canadian philosopher Paul Thagard explained that "when people say that [Spears] is the new Madonna, they do not literally mean that [she] is Madonna. Rather, they are pointing out some systematic similartities between the two".[221] In a general overview of this title, Billboard magazine explained in 2017 that a Madonna "has to assume the role of a commander standing at the frontlines for womanhood" as well "the controversial complexities of human sexuality, despite the inevitable blacklash to ensue".[220] They added other elements such as a Madonna "has to be a trend-setter" or a muse for producers, songwriters, fashion designers or directors alike and match both her record sales or achievements.[220] Givin another general sense of this treatment applied to several artists, biographers Isa Muguruza and Los Prieto Flores wrote in 2021, that every so often "there is a Mexican Madonna, a Latina Madonna and even a Black Madonna" and that's because she "transcended her own figure" and because she is "almost a powerful adjective that translates into a way of doing things".[222]

As illustrative examples starting in the 1980s, a couple of female performers were planned or initially promoted by their record labels as "a Madonna", including artists such as Martika by CBS Records or La India by Reprise, which this led to chose her stage name for the latter.[223][224] Ana Curra said that in her case Hispavox planned to promote her as the "Spanish Madonna".[225] In the early-1990s, this phenomenon was described by Gloria Trevi in an interview with Los Angeles Times: "Many artists in Mexico fight to be the Latina Madonna".[226] Trevi also received the tag of "Latina Madonna" or "Mexican Madonna".[226] In the following three decades: 2000s, 2010s and 2020s a varied artists such as Rihanna, Anitta or Dua Lipa have received the tag by multiple international publications.[220][227][228] Additional illustrative examples across different region and continents, include German singer Sandra whose was called "the Madonna of Europe" as reported publications such as Music & Media in the mid-1980s.[229] Singer Alisha Chinai gained notoriety as "the Indian Madonna" according to professors of ethnomusicology, Gregory D. Booth and Bradley Shope,[230] while South African artist, Brenda Fassie was nicknamed a "Madonna" and that treatment received significant attention by sources such as Time magazine.[231] In 2015, Madonna herself called Kanye West either the "new" or "Black Madonna".[232]

Many of these artists have commented the comparison or nickname with mixed responses with Lady Gaga saying: "I always used to say to people, when they would say, 'Oh, she's the next Madonna.' No, I'm the next Iron Maiden".[233] Beyond commentaries from media and own artists, references in musical pieces include songs or albums. For example, artists such as Venus D-Lite, Sarit Hadad or Hi Fashion released songs with the title "I'm Not Madonna".[234][235] Indian rapper Baba Sehgal titled an album Main Bhi Madonna (I Am Also Madonna),[230] while Eminem included a verse in "Fubba U cubba cubba".

Contradictory perspective[]

Associate professor Diane Pecknold wrote in American Icons (2006) that Madonna "was not only an omnipresent figure but a polarizing one".[33] Critical theorist, Stuart Sim wrote that "Madonna now attained the status of cultural icon, she is however, an extremely problematic one" concluding that "makes her exceedingly difficult to categorize; depending on one's point of view".[236] Scholar Audra Gaugler from Lehigh University also explained that "there exists a large band of critics that at first praised her, but then became disillusioned with her as she became more and more controversial".[34]

During her career, Madonna attracted the attention of family organizations, feminist anti-porn and religious groups worldwide with boycott or protests. For authors like Jock McGregor of Christian organization L'Abri "the sector of society most offended by Madonna, has been Christian community".[79] Professor and minister Bruce Forbes expressed that "some of the most important and interesting texts in recent American culture which have overlapping concerns with liberation theologies are by Madonna".[237]

As some critics found that Madonna has proved a master of cultural appropriation,[181] professor of sociology and author David Chaney documented in his book The Cultural Turn (1994) that "for many political activists, the more unsettling implication is that Madonna has destabilised fundamental signs of subcultural membership. Even if her stardom is now exhausted". He further asserted that "the possibility of her existence" (as with other figures) is that "all marks of identity are arbitrary, then any form of being becomes pastiche".[238] Sociologist John Shepherd wrote that Madonna's cultural practices highlight the "sadly continuing social realities of dominance and subordination".[239] Educator John R. Silber lumped Madonna with Adolf Hitler and Saddam Hussein.[240]

Author of Sex symbols (1999) commented that Madonna "has pushed the boundaries that most women do not wish to broach".[51] In the height of her career, some observers such as Italian critic Achille Bonito Oliva and academic Camille Paglia found that for some "Madonna restored the [image of] Whore of Babylon, the pagan goddess banned by the last book of the Bible".[241][61] Authors of the academic compendium The Madonna Connection explained "another mythical feminine monster summoned up to make sense of Madonna is the succubus".[242] Many years after, Jewish rabbi Shmuley Boteach said in 2004: "For more than two decades, Madonna has been allowed to destroy the female recording industry by erasing the line that separates music from pornography" which he described as a "truly frightening" and added that "Madonna and her ilk have spawned a tragic world".[55] Similarly, professor Sheila Jeffreys and Cheryl Overs agreed that "Madonna was an important element in normal-izing the prostitute look as high fashion" and aided in the normalization of prostitution in the malestream culture.[243]

Authors in Representing gender in cultures (2004) noted that "Madonna has been consistently denied a status of a 'real' musician",[244] while for Belgian critic Luc Sante she is "a barely adequate singer".[132] Ludovic Hunter-Tilney from Financial Times noted that to her critics she "is right to describe herself as a businesswoman but wrong to call herself an artist".[245] Writer Michael Campbell felt that "neither Jackson nor Madonna has been a musical innovator", although explained that "their most influential and innovative contributions have come in other areas".[246] In another ambivalent point, Australian public intellectual Germaine Greer admitted she is of the opinion shared by many that "she can neither dance nor sing" but described that "Madonna has the one talent that really matters in the 21st century" which is "marketing".[247]

Criticisms around the world[]

Scottish music writer Alan McGee observed that she "has been banned by countries",[118] while professor Ann Cvetkovich once remarked that a global figure such as Madonna "can be articulated in highly contradictory ways".[174] Contradictory social attention to Madonna can be found in numerous facets around the world, while is particular visible in some groups and regions. In 2016, head of British pro-North Korea group blamed Madonna for the collapse of the Soviet Union by making people listen to "the most rubbishy aspects of bourgeois imperialist pop culture".[248] Another allegation within this context came from Russian journalist Maksim Shevchenko whose wrote in 2012 that she is part of "a vivid symbol of everything superficial, deceitful and hateful that the West exhibits toward Russia".[249]

Political advisor Aaron Klein in his book Schmoozing with Terrorists (2007) informed that in the Middle East "everyone has heard of her" and "the terrorists know Madonna because she is regularly referenced" for "corrupting humanity on earth". He also pointed "when sheikhs cite samples of the U.S. attempting to pervert young Muslims with our demonic culture, they speak of Madonna".[189] In the following decade, International Music Council informed in 2015 that Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) classified both her music and performances as haram stating that "represent anti-Islamic values".[250] Middle East scholar Patrick Clawson also found that "Iranian radicals reject" Madonna.[251] Her decision to perform at the Eurovision Song Contest 2019 raised criticism among a group of activists, academics and intellectuals Palestinian from PACBI to BDS.[252]

She has received death threats by numerous groups as her cultural influence is largely perceived as negative by them. The Australian Associated Press (AAP) observed in 2004, that Palestinian terrorists threatened to kill her "because she represents many things they hate about the West". After this, she cancelled three concerts in Israel.[253] In 2006, it was reported that crime bosses from Russian mafia threatened to kill her when she was on tour.[254] In 2009, she also received threats from Muslim extremists in Israel as informed historian and journalist Yossi Melman,[255] and same situation occurred in Serbia according to the agency IANS.[256]

Researchers at the University of Liverpool labelled the "Madonna effect" to the international adoptions and social issues followed by her first process in 2006. At that time, the child psychologist Kevin Browne found that closely related with the Madonna-style process, there were a rise in the number of children in orphanages across Europe due the trend of international adoptions. They also perceived that some parents in poor countries were giving up their children "in the belief that they will have a 'better life in the west' with a more wealthy family".[257] When she planned to adopt again in 2017, some activists warned that Madonna's act "would facilitate the child trafficking in Africa".[258] As an Italian American figure, Italian sculptor Walter Pugni planned in 1988 a statue of Madonna in Pacentro, where are from her paternal grandparents, noting that "Madonna is a symbol of our children and represents a better world in the year 2000". The then mayor of the comune opposed to that idea as well Madonna's Italian relatives.[259][260]

Counter-responses[]

British reader Deborah Jermyn of Roehampton University wrote in 2016, that "numerous academic studies have considered the way Madonna polarises views".[175] While her criticism have generated significant analysis and counter-responses, Maria Gallagher wrote for The Philadelphia Inquirer in 1992, that "there is no avoiding Madonna, so we might as well study her". She found sociologist Cindy Patton described that "[Madonna is] a social critic in a certain way" and "has an instinct for not just what's going to get people upset, but what's going to get people thinking".[261] Many years after, Süddeutsche Zeitung journalist Caroline von Lowtzow asserted in the late-2000s that interpreting Madonna has never been only a domain of tabloid media.[262]

Musicologist Susan McClary suggests that Madonna is engaged in rewriting some very fundamental levels of Western thought.[239] Scholar Gaugler advocated for the singer expressing that "she has faced much criticism throughout her career, but much of it is unjust".[34] In the perception of marketer and professor Stephen Brown from University of Ulster "what people say about Madonna says more about them than it says about the singer".[122] Stan Hawkins from University of Leeds expressed in the late-1990s that "Madonna's act[s] can only infuriate those who are unfamiliar with the everyday forms of human expression visible in commercials, films, videos, fashion, literature, art and journalism".[184]

Another consideration came from Canadian scholar Samantha C. Thrift of Simon Fraser University whose said "the body of criticism inspired by Madonna's cultural production opened avenues for feminist analysis" for other figures such as Martha Stewart.[263] Professor and economist Robert C. Allen summarized that Madonna is "the site of whole series of discourses, many of which contradict each other but which together produce the divergent images of circulation".[264] Dutch academics in the article Madonna as a symbol of reflexive modernisation (2013) viewed her as a "symbol" and "representation" and propose that "the communication of social and cultural tensions embodied in Madonna, explain the unparalleled public and scientific fascination for this cultural phenomenon".[265] In a 2005 international congress, Catalan translator and assistant professor Lydia Brugué of Universitat de Vic gives her sympathetic view:

Madonna is an artist with multiple message leading frequently to ambiguity. It provokes, it's true, but it goes beyond creating controversy. Her influence in society is titanic and raises criticism not only among madonophobic and madonophilic feminist groups, but also in most of world population.[266]

The statement of Norman Mailer when he "defended" Madonna calling her as "our greatest living female artist" has been also cited by others.[107] In her article You Don't Know Madonna (2002) American novelist Jennifer Egan questioned commentaries from others critics such those arguing that "Madonna has no real talent". While she confessed was part of that general perception retrospectively viewed them as an "old one".[132] She also found sense remarking that "music per se has never encompassed the full range of Madonna's aspirations" when she once commented to the media: "I know I'm not the best singer, and I know I'm not the best dancer. But I'm not interested in that" but in being "political".[132]

Critics' lists and polls[]

As she appeared in various listicles during her career, associate professor Diane Pecknold shared her observation in 2006 saying that "nearly any poll of the biggest, greatest, or best in popular culture includes her name".[153] Similarly, The Daily Telegraph editor William Langley documented in 2011 that she has been a fixture of several "list of world's most powerful/admired/influential women".[267] According to Acclaimed Music, which statistically aggregates hundreds of critics' lists, Madonna is the most acclaimed woman in music history.[268] Some illustrative examples include:

| Year | Publication | List or Work | Rank | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Adams Media | 365 Women Who Made Difference | n/a | [269] |

| 1998 | Ladies' Home Journal | 100 Most Important Women of the 20th Century | n/a | [270] |

| 1998 | Friedman/Fairfax Publishers | 100 Remarkable Women of the 20th Century | n/a | [271] |

| 1999 | ABC-Clio | Notable Women in American History 500 of the most notable women in American history |

n/a | [272] |

| 2002 | VH1 | 100 Greatest Women in Music (Poll) | 1 | [273] |

| 2003 | VH1 | 50 Greatest Women of the Video Era | 1 | [274] |

| 2003 | People/VH1 | 200 Greatest Pop Culture Icons | n/a | [275] |

| 2005 | Discovery Channel | 100 Greatest Americans | n/a | [276] |

| 2005 | Variety | 100 Icons of the Century | n/a | [277] |

| 2007 | Quercus | 50 Women Who Changed the World | n/a | [278] |

| 2008 | Encyclopædia Britannica | 100 Most Influential Americans | n/a | [279] |

| 2009 | Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. | The 100 Most Influential Musicians of All Time | n/a | [280] |

| 2010 | Time | 25 Most Powerful Women of the Past Century | n/a | [211] |

| 2011 | The Guardian | Top 100 women: art, film, music and fashion | n/a | [40] |

| 2012 | VH1 | 100 Greatest Women in Music | 1 | [281] |

| 2012 | Time | All-Time 100 Fashion Icons | n/a | [69] |

| 2014 | Smithsonian Institution | 100 Most Significant Americans of All Time | n/a | [282] |

| 2014 | University of Toulouse | Wikipedia's most influential people (Based on all languages ranked) |

n/a | [283] |

| 2015 | The Daily Telegraph | Pop's 20 Greatest Female Artists | 1 | [284] |

| 2016 | Esquire | The 75 Greatest Women of All Time | n/a | [285] |

| 2019 | Encyclopædia Britannica | 100 Women | n/a | [111] |

| 2019 | Time | 100 Women of the Year: 1989 (100 women who defined the last century) |

n/a | [286] |

| 2019 | Laurence King Publishing | 100 Women 100 Styles (The Women Who Changed the Way We Look) |

n/a | [287] |

Cultural depictions[]

- Nota bene: This section only include some examples

Madonna's life and career have been depicted in film, television, literature, music, arts, and even science. In a general sense, academic Georges Claude Guilbert found that she "is the ultimate reference in several domains" and her "likeness" has been exhibited in museums.[24]

In 2006, a new water bear species, Echiniscus madonnae, was named after her. The paper with the description of E. madonnae was published in the international journal of animal taxonomy Zootaxa in March 2006 (Vol. 1154, pp. 1–36). The Zoologists commented: "We take great pleasure in dedicating this species to one of the most significant artists of our times, Madonna Louise Veronica Ritchie".[288][289] Numerous contemporary artists have been inspired in Madonna. A book called Madonna In Art (2004) compiled pictures of the singer in art form by over 116 artists from 23 countries, including Andrew Logan, Sebastian Krüger, Al Hirschfeld, and Peter Howson.[290]

Madonna has been subject of music collectors and was classified at number one in the 100 Most Collectable Divas by Record Collector in 2008.[291] Her songs have been covered by numerous performers in multiple languages and she also inspired the creation of new musical singles. In 2002, Australian rock band The Androids scored a top-five hit single on the ARIA Chart with "Do It with Madonna".[292] English singer Robbie Williams released "She's Madonna" in 2006, which reached the top five in many European countries. The song talks about his fascination with Madonna, and is a reference to Guy Ritchie who left his ex-girlfriend Tania Strecker for Madonna.[293] In 2010, South Korean girl group Secret reached number one on the Gaon Singles Chart with the song "Madonna" from the EP of the same name.[294] According to its songwriters, the song is about "living with confidence by becoming an icon in this generation, like the American star Madonna".[295]

See also[]

- Madonna studies: Madonna's impact on academia

- Madonna wannabe

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hughes, Hilary (October 14, 2016). "MADONNA IS THE QUEEN OF POP (AND ALSO 2016, ACCORDING TO BILLBOARD)". MTV. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Annalee, Newitz (November 1993). "Madonna's Revenge". EServer.org. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ana, Laglere (April 14, 2015). "9 razones que explican por qué Madonna es la Reina del Pop de todos los tiempos" [9 reasons explain why Madonna is the Queen of Pop of all time] (in Spanish). Batanga.com. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b von Aue, Mary (October 24, 2014). "WHY MADONNA'S UNAPOLOGETIC 'BEDTIME STORIES' IS HER MOST IMPORTANT ALBUM". Vice. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Robinson, Peter (March 5, 2011). "Madonna inspired modern pop stars". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Boesveld, Sarah (June 27, 2017). "Camille Paglia cuts the 'malarkey': Women just need to toughen up". Chatelaine. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Ospina, Ana María (August 21, 2018). "Madonna, un paradigma de la post-modernidad" (in Spanish and French). Radio France Internationale. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Powers, Ann (March 1, 1998). "POP VIEW; New Tune for the Material Girl: I'm Neither". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kakutani, Michiko (October 21, 1992). "Books of The Times; Madonna Writes; Academics Explore Her Erotic Semiotics". The New York Times. pp. 1–3. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pendle, George (2005). "I'm Looking Through You On the slip of the icon". Bidoun. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ McNair 2002, p. 69

- ^ Faith, Karlene (1997). Madonna, Bawdy & Soul. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 1442676884. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt2tv4xw#.

- ^ Benson & Metz 1999, p. 240

- ^ Saroyan, Strawberry; Goldberg, Michelle (October 10, 2000). "So-called Chaos". Salon. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Duro Pop (2018). The Transformation of Ancient Heroes and the Reappropriation of Myths. The Age of Promiscuity. Lexington Books. p. 91. ISBN 978-1498580618. Retrieved May 4, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Stange, Mary Zeiss; Oyster, Carol K.; Sloan, Jane E. (2011). Madonna. SAGE Publishing. p. 877. ISBN 978-1412976855. Retrieved May 4, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Harrington, Rebecca (July 26, 2013). "Madonna's Diet Is the Hardest I Have Ever Tried". The Cut. Archived from the original on May 16, 2020.

- ^ Langley, William (August 9, 2008). "Madonna, mistress of metamorphosis". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on September 1, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tavana, Art (May 15, 2014). "Madonna was better than Michael Jackson". Death & Taxes. SpinMedia. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Muller, Marissa G. (August 16, 2018). "The 9 Things Madonna Invented That You Didn't Realize Madonna Invented". W. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ Hall & Hall 2006, p. 51

- ^ Jump up to: a b García, Sergio (October 9, 2015). ""Madonna usa los videoclips para dar mensajes diferentes a los de sus canciones"". El Comercio. Archived from the original on October 20, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Aguilar Guzmán 2010, p. 88

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Guilbert, Georges Claude (2015) [1st pub. 2002]. "1". Madonna as Postmodern Myth. McFarland & Company. pp. 1–22, 88–89. ISBN 978-0786480715. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Cullen 2001, p. 86

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith-Shomade 2002, p. 162

- ^ Marcus, Sara (February 3, 2012). "How Madonna liberated America". Salon. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ Jeansonne 2006, p. 446

- ^ Guilbert 2002, pp. 41–43

- ^ Jump up to: a b Danesi, Marcel (2020). "4.1.3 Vocabulary". Language, Society, and New Media: Sociolinguistics Today. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-0000-4876-6. Retrieved March 31, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ "icon". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "icono o ícono". Diccionario panhispánico de dudas (in Spanish). Royal Spanish Academy. 2005. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hall & Hall 2006, p. 446

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gaugler, Audra (2000). "Madonna, an American pop icon of feminism and counter-hegemony : blurring the boundaries [sic] of race, gender, and sexuality by Audra Gaugler". Lehigh University. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Steyn, Mark (July 10, 2014) [1st pub. 1996]. Broadway Babies Say Goodnight Musicals Then and Now. ISBN 978-1-1366-8508-8. Retrieved March 29, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Appignanesi & Garratt 2014, p. 148

- ^ Barcella, Laura; Valenti, Jessica (March 6, 2012). Madonna and Me: Women Writers on the Queen of Pop. ISBN 978-1-5937-6429-6. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021.

- ^ Jhally 2006, p. 194

- ^ Paglia, Camille (December 14, 1990). "Madonna – Finally, A Real Feminist". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Khaleeli, Homa (March 8, 2011). "Madonna". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Lenore, Victor; Rubio, Irene G. (June 26, 2012). "Madonna: ¿icono feminista o tótem consumista?" [Madonna: feminist icon or consumerist totem?]. Diagonal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Reist, Melinda Tankard (March 16, 2016). "Madonna: Turning her back on the cause of women". SBS Australia. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ "Madonna". New Internationalist (222). August 5, 1991. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ "How Madonna May Have Been Influenced by Mae West: CLOSED CAPTIONS". American Masters. PBS. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Smith 2011, p. 119

- ^ Klosterman 2003, p. 83

- ^ Gross, Alan G. (2018). From Black Holes to the Big Bang. The Scientific Sublime: Popular Science Unravels the Mysteries of the Universe. Oxford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0190637774. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Fouz-Hernandez, Santiago; Jarman, Freya (2017) [1st pub. 2004]. "Introduction". Madonna's drowned worlds resurface. Madonna's Drowned Worlds: New Approaches to Her Cultural Transformations, 1983-2003. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-1351559539. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Leigh, Wendy; Karten, Stephen (1999) [1st pub. 1993]. Prince Charming: The John F. Kennedy Jr. Story. Signet Press. p. 253. ISBN 0451409213. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Benstock & Ferriss 1994, p. 168

- ^ Jump up to: a b Leigh-Kile 1999, p. 15

- ^ Hopkins, Dr. Susan (2002). Girl Heroes: The New Force in Popular Culture. Pluto Press. p. 41. ISBN 1864031573. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ "Putting sex in sexagenarian: Madonna still shocks at 60". France 24. August 12, 2018. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Gundersen, Edna (August 17, 2008). "Pop icons at 50: Madonna". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sorry, but you cant be a kabbalist and strip on stage". J. The Jewish News of Northern California. July 24, 2004. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "Material whirl". New Statesman. September 18, 2000. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anderson, Jaime; Kupp, Martin (2006). "Madonna – Strategy on the Dance Floor" (PDF). European School of Management and Technology (ESMT). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ Garde-Hansen, Joanne (2011). Media and Memory. Edinburgh University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0748688883. Retrieved April 3, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ McClary, Susan (1991). "Chapter 7 Living to Tell: Madonna's Resurrection of the Fleshly". Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality: 148–166. JSTOR 10.5749/j.ctttt886. Retrieved March 29, 2021 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Mills, Sara (1994). Freedom, Feeling and Dancing. Gendering the Reader. Harvester Wheatsheaf. p. 71. ISBN 978-0745011301. Retrieved May 10, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Blanco, José F. (December 2014). "How to Fashion an Archetype: Madonna as Anima Figure". The Journal of Popular Culture. 47 (6): 1153–1166. doi:10.1111/jpcu.12203. Retrieved March 29, 2021 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ^ Benstock & Ferriss 1994, p. 176

- ^ "Madonna Birthday: How the 'Material Girl' has shaped modern fashion trends". The Independent. August 16, 2020. Archived from the original on August 21, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ Wark 1999, p. 80

- ^ Karaminas & Geczy 2013, p. 38

- ^ Jump up to: a b Asitimbay 2005, p. 148

- ^ Jump up to: a b Guilbert 2002, p. 37