Curiosity (rover)

| Curiosity | |

|---|---|

| Part of Mars Science Laboratory | |

Self-portrait of Curiosity located at the foothill of Mount Sharp (6 October 2015) | |

| Type | Mars rover |

| Manufacturer |

|

| Technical details | |

| Dry mass | 899 kg (1,982 lb) [1] |

| Flight history | |

| Launch date | 26 November 2011, 15:02:00 UTC[2][3][4] |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral (CCAFS), SLC-41 |

| Landing date | 6 August 2012, 05:17:57 UTC [5][6] MSD 49269, 05:53 AMT MSD 49269, 14:53 LMST (Sol 0) |

| Landing site | Gale crater 4°35′22″S 137°26′30″E / 4.5895°S 137.4417°ECoordinates: 4°35′22″S 137°26′30″E / 4.5895°S 137.4417°E |

| Total hours | 79321 since landing [7] |

| Distance traveled | 26.06 km (16.19 mi) [8] as of 10 August 2021 |

Mars Science Laboratory mission patch NASA Mars rovers | |

Curiosity is a car-sized Mars rover designed to explore the Gale crater on Mars as part of NASA's Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission.[2] Curiosity was launched from Cape Canaveral (CCAFS) on 26 November 2011, at 15:02:00 UTC and landed on Aeolis Palus inside Gale crater on Mars on 6 August 2012, 05:17:57 UTC.[5][6][9] The Bradbury Landing site was less than 2.4 km (1.5 mi) from the center of the rover's touchdown target after a 560 million km (350 million mi) journey.[10][11]

The rover's goals include an investigation of the Martian climate and geology, assessment of whether the selected field site inside Gale has ever offered environmental conditions favorable for microbial life (including investigation of the role of water), and planetary habitability studies in preparation for human exploration.[12][13]

In December 2012, Curiosity's two-year mission was extended indefinitely,[14] and on 5 August 2017, NASA celebrated the fifth anniversary of the Curiosity rover landing.[15][16] The rover is still operational, and as of August 24, 2021, Curiosity has been active on Mars for 3217 sols (3305 total days; 9 years, 18 days) since its landing (see current status).

The NASA/JPL Mars Science Laboratory/Curiosity Project Team was awarded the 2012 Robert J. Collier Trophy by the National Aeronautic Association "In recognition of the extraordinary achievements of successfully landing Curiosity on Mars, advancing the nation's technological and engineering capabilities, and significantly improving humanity's understanding of ancient Martian habitable environments."[17] Curiosity's rover design serves as the basis for NASA's 2021 Perseverance mission, which carries different scientific instruments.

Mission[]

Goals and objectives[]

As established by the Mars Exploration Program, the main scientific goals of the MSL mission are to help determine whether Mars could ever have supported life, as well as determining the role of water, and to study the climate and geology of Mars.[12][13] The mission results will also help prepare for human exploration.[13] To contribute to these goals, MSL has eight main scientific objectives:[18]

- Biological

- Determine the nature and inventory of organic carbon compounds

- Investigate the chemical building blocks of life (carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur)

- Identify features that may represent the effects of biological processes (biosignatures and biomolecules)

- Geological and geochemical

- Investigate the chemical, isotopic, and mineralogical composition of the Martian surface and near-surface geological materials

- Interpret the processes that have formed and modified rocks and soils

- Planetary process

- Assess long-timescale (i.e., 4-billion-year) Martian atmospheric evolution processes

- Determine present state, distribution, and cycling of water and carbon dioxide

- Surface radiation

- Characterize the broad spectrum of surface radiation, including galactic and cosmic radiation, solar proton events and secondary neutrons. As part of its exploration, it also measured the radiation exposure in the interior of the spacecraft as it traveled to Mars, and it is continuing radiation measurements as it explores the surface of Mars. This data would be important for a future crewed mission.[19]

About one year into the surface mission, and having assessed that ancient Mars could have been hospitable to microbial life, the MSL mission objectives evolved to developing predictive models for the preservation process of organic compounds and biomolecules; a branch of paleontology called taphonomy.[20] The region it is set to explore has been compared to the Four Corners region of the North American west.[21]

Name[]

A NASA panel selected the name Curiosity following a nationwide student contest that attracted more than 9,000 proposals via the Internet and mail. A sixth-grade student from Kansas, 12-year-old Clara Ma from Sunflower Elementary School in Lenexa, Kansas, submitted the winning entry. As her prize, Ma won a trip to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, where she signed her name directly onto the rover as it was being assembled.[22]

Ma wrote in her winning essay:

Curiosity is an everlasting flame that burns in everyone's mind. It makes me get out of bed in the morning and wonder what surprises life will throw at me that day. Curiosity is such a powerful force. Without it, we wouldn't be who we are today. Curiosity is the passion that drives us through our everyday lives. We have become explorers and scientists with our need to ask questions and to wonder.[22]

Cost[]

Adjusted for inflation, Curiosity has a life-cycle cost of US$3.2 billion in 2020 dollars. By comparison, the 2021 Perseverance rover has a life-cycle cost of US$2.9 billion.[23]

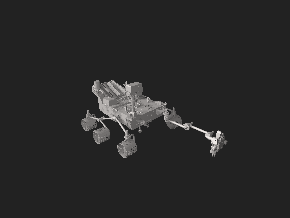

Rover and lander specifications[]

Curiosity is 2.9 m (9 ft 6 in) long by 2.7 m (8 ft 10 in) wide by 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) in height,[24] larger than Mars Exploration Rovers, which are 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) long and have a mass of 174 kg (384 lb) including 6.8 kg (15 lb) of scientific instruments.[25][26][27] In comparison to Pancam on the Mars Exploration Rovers, the MastCam-34 has 1.25× higher spatial resolution and the MastCam-100 has 3.67× higher spatial resolution.[28]

Curiosity has an advanced payload of scientific equipment on Mars.[29] It is the fourth NASA robotic rover sent to Mars since 1996. Previous successful Mars rovers are Sojourner from the Mars Pathfinder mission (1997), and Spirit (2004–2010) and Opportunity (2004–2018) rovers from the Mars Exploration Rover mission.

Curiosity comprised 23% of the mass of the 3,893 kg (8,583 lb) spacecraft at launch. The remaining mass was discarded in the process of transport and landing.

- Dimensions: Curiosity has a mass of 899 kg (1,982 lb) including 80 kg (180 lb) of scientific instruments.[25] The rover is 2.9 m (9 ft 6 in) long by 2.7 m (8 ft 10 in) wide by 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) in height.[24]

The main box-like chassis forms the Warm Electronics Box (WEB).[30]:52

- Power source: Curiosity is powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), like the successful Viking 1 and Viking 2 Mars landers in 1976.[31][32]

- Radioisotope power systems (RPSs) are generators that produce electricity from the decay of radioactive isotopes, such as plutonium-238, which is a non-fissile isotope of plutonium. Heat given off by the decay of this isotope is converted into electric voltage by thermocouples, providing constant power during all seasons and through the day and night. Waste heat is also used via pipes to warm systems, freeing electrical power for the operation of the vehicle and instruments.[31][32] Curiosity's RTG is fueled by 4.8 kg (11 lb) of plutonium-238 dioxide supplied by the U.S. Department of Energy.[33]

- Curiosity's RTG is the Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG), designed and built by Rocketdyne and Teledyne Energy Systems under contract to the U.S. Department of Energy,[34] and fueled and tested by the Idaho National Laboratory.[35] Based on legacy RTG technology, it represents a more flexible and compact development step,[36] and is designed to produce 110 watts of electrical power and about 2,000 watts of thermal power at the start of the mission.[31][32] The MMRTG produces less power over time as its plutonium fuel decays: at its minimum lifetime of 14 years, electrical power output is down to 100 watts.[37][38] The power source generates 9 MJ (2.5 kWh) of electrical energy each day, much more than the solar panels of the now retired Mars Exploration Rovers, which generated about 2.1 MJ (0.58 kWh) each day. The electrical output from the MMRTG charges two rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. This enables the power subsystem to meet peak power demands of rover activities when the demand temporarily exceeds the generator's steady output level. Each battery has a capacity of about 42 ampere hours.

- Heat rejection system: The temperatures at the landing site can vary from −127 to 40 °C (−197 to 104 °F); therefore, the thermal system warms the rover for most of the Martian year. The thermal system does so in several ways: passively, through the dissipation to internal components; by electrical heaters strategically placed on key components; and by using the rover heat rejection system (HRS).[30] It uses fluid pumped through 60 m (200 ft) of tubing in the rover body so that sensitive components are kept at optimal temperatures.[39] The fluid loop serves the additional purpose of rejecting heat when the rover has become too warm, and it can also gather waste heat from the power source by pumping fluid through two heat exchangers that are mounted alongside the RTG. The HRS also has the ability to cool components if necessary.[39]

- Computers: The two identical on-board rover computers, called Rover Compute Element (RCE) contain radiation hardened memory to tolerate the extreme radiation from space and to safeguard against power-off cycles. The computers run the VxWorks real-time operating system (RTOS). Each computer's memory includes 256 kilobyte (kB) of EEPROM, 256 Megabyte (MB) of Dynamic random-access memory (DRAM), and 2 Gigabyte (GB) of flash memory.[40] For comparison, the Mars Exploration Rovers used 3 MB of EEPROM, 128 MB of DRAM, and 256 MB of flash memory.[41]

- The RCE computers use the RAD750 Central processing unit (CPU), which is a successor to the RAD6000 CPU of the Mars Exploration Rovers.[42][43] The IBM RAD750 CPU, a radiation-hardened version of the PowerPC 750, can execute up to 400 Million instructions per second (MIPS), while the RAD6000 CPU is capable of up to only 35 MIPS.[44][45] Of the two on-board computers, one is configured as backup and will take over in the event of problems with the main computer.[40] On 28 February 2013, NASA was forced to switch to the backup computer due to a problem with the active computer's flash memory, which resulted in the computer continuously rebooting in a loop. The backup computer was turned on in safe mode and subsequently returned to active status on 4 March 2013.[46] The same problem happened in late March, resuming full operations on 25 March 2013.[47]

- The rover has an inertial measurement unit (IMU) that provides 3-axis information on its position, which is used in rover navigation.[40] The rover's computers are constantly self-monitoring to keep the rover operational, such as by regulating the rover's temperature.[40] Activities such as taking pictures, driving, and operating the instruments are performed in a command sequence that is sent from the flight team to the rover.[40] The rover installed its full surface operations software after the landing because its computers did not have sufficient main memory available during flight. The new software essentially replaced the flight software.[11]

- The rover has four processors. One of them is a SPARC processor that runs the rover's thrusters and descent-stage motors as it descended through the Martian atmosphere. Two others are PowerPC processors: the main processor, which handles nearly all of the rover's ground functions, and that processor's backup. The fourth one, another SPARC processor, commands the rover's movement and is part of its motor controller box. All four processors are single core.[48]

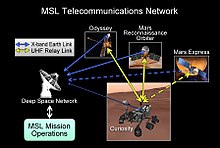

Communications[]

- Communications: Curiosity is equipped with significant telecommunication redundancy by several means: an X band transmitter and receiver that can communicate directly with Earth, and a Ultra high frequency (UHF) Electra-Lite software-defined radio for communicating with Mars orbiters.[30] Communication with orbiters is the main path for data return to Earth, since the orbiters have both more power and larger antennas than the lander, allowing for faster transmission speeds.[30] Telecommunication included a small deep space transponder on the descent stage and a solid-state power amplifier on the rover for X-band. The rover also has two UHF radios,[30] the signals of which orbiting relay satellites are capable of relaying back to Earth. Signals between Earth and Mars take an average of 14 minutes, 6 seconds.[49] Curiosity can communicate with Earth directly at speeds up to 32 kbit/s, but the bulk of the data transfer is being relayed through the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Odyssey orbiter. Data transfer speeds between Curiosity and each orbiter may reach 2000 kbit/s and 256 kbit/s, respectively, but each orbiter is able to communicate with Curiosity for only about eight minutes per day (0.56% of the time).[50] Communication from and to Curiosity relies on internationally agreed space data communications protocols as defined by the Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems.[51]

- Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) is the central data distribution hub where selected data products are provided to remote science operations sites as needed. JPL is also the central hub for the uplink process, though participants are distributed at their respective home institutions.[30] At landing, telemetry was monitored by three orbiters, depending on their dynamic location: the 2001 Mars Odyssey, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and ESA's Mars Express satellite.[52] As of February 2019, the MAVEN orbiter is being positioned to serve as a relay orbiter while continuing its science mission.[53]

Mobility systems[]

- Mobility systems: Curiosity is equipped with six 50 cm (20 in) diameter wheels in a rocker-bogie suspension. These are scaled versions of those used on Mars Exploration Rovers (MER).[30] The suspension system also served as landing gear for the vehicle, unlike its smaller predecessors.[54][55] Each wheel has cleats and is independently actuated and geared, providing for climbing in soft sand and scrambling over rocks. Each front and rear wheel can be independently steered, allowing the vehicle to turn in place as well as execute arcing turns.[30] Each wheel has a pattern that helps it maintain traction but also leaves patterned tracks in the sandy surface of Mars. That pattern is used by on-board cameras to estimate the distance traveled. The pattern itself is Morse code for "JPL" (·--- ·--· ·-··).[56] The rover is capable of climbing sand dunes with slopes up to 12.5°.[57] Based on the center of mass, the vehicle can withstand a tilt of at least 50° in any direction without overturning, but automatic sensors limit the rover from exceeding 30° tilts.[30] After six years of use, the wheels are visibly worn with punctures and tears.[58]

- Curiosity can roll over obstacles approaching 65 cm (26 in) in height,[29] and it has a ground clearance of 60 cm (24 in).[59] Based on variables including power levels, terrain difficulty, slippage and visibility, the maximum terrain-traverse speed is estimated to be 200 m (660 ft) per day by automatic navigation.[29] The rover landed about 10 km (6.2 mi) from the base of Mount Sharp,[60] (officially named Aeolis Mons) and it is expected to traverse a minimum of 19 km (12 mi) during its primary two-year mission.[61] It can travel up to 90 m (300 ft) per hour but average speed is about 30 m (98 ft) per hour.[61] The vehicle is 'driven' by several operators led by Vandi Verma, group leader of Autonomous Systems, Mobility and Robotic Systems at JPL,[62][63] who also cowrote the PLEXIL language used to operate the rover.[64][65][66]

Landing[]

Curiosity landed in Quad 51 (nicknamed Yellowknife) of Aeolis Palus in the crater Gale.[67][68][69][70] The landing site coordinates are: 4°35′22″S 137°26′30″E / 4.5895°S 137.4417°E.[71][72] The location was named Bradbury Landing on 22 August 2012, in honor of science fiction author Ray Bradbury.[10] Gale, an estimated 3.5 to 3.8 billion-year-old impact crater, is hypothesized to have first been gradually filled in by sediments; first water-deposited, and then wind-deposited, possibly until it was completely covered. Wind erosion then scoured out the sediments, leaving an isolated 5.5 km (3.4 mi) mountain, Aeolis Mons ("Mount Sharp"), at the center of the 154 km (96 mi) wide crater. Thus, it is believed that the rover may have the opportunity to study two billion years of Martian history in the sediments exposed in the mountain. Additionally, its landing site is near an alluvial fan, which is hypothesized to be the result of a flow of ground water, either before the deposition of the eroded sediments or else in relatively recent geologic history.[73][74]

According to NASA, an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 heat-resistant bacterial spores were on Curiosity at launch, and as much as 1,000 times that number may not have been counted.[75]

Rover's landing system[]

Previous NASA Mars rovers became active only after the successful entry, descent and landing on the Martian surface. Curiosity, on the other hand, was active when it touched down on the surface of Mars, employing the rover suspension system for the final set-down.[76]

Curiosity transformed from its stowed flight configuration to a landing configuration while the MSL spacecraft simultaneously lowered it beneath the spacecraft descent stage with a 20 m (66 ft) tether from the "sky crane" system to a soft landing—wheels down—on the surface of Mars.[77][78][79][80] After the rover touched down it waited 2 seconds to confirm that it was on solid ground then fired several pyrotechnic fasteners activating cable cutters on the bridle to free itself from the spacecraft descent stage. The descent stage then flew away to a crash landing, and the rover prepared itself to begin the science portion of the mission.[81]

Travel status[]

As of 9 December 2020, the rover was 23.32 km (14.49 mi) away from its landing site.[82] As of 17 April 2020, the rover has been driven on fewer than 800 of its 2736 sols (Martian days).

Duplicate[]

Curiosity has a twin rover used for testing and problem solving, MAGGIE (Mars Automated Giant Gizmo for Integrated Engineering), a vehicle system test bed (VSTB). It is housed at the JPL Mars Yard for problem solving on simulated Mars terrain.[83][84]

Scientific instruments[]

The general sample analysis strategy begins with high-resolution cameras to look for features of interest. If a particular surface is of interest, Curiosity can vaporize a small portion of it with an infrared laser and examine the resulting spectra signature to query the rock's elemental composition. If that signature is intriguing, the rover uses its long arm to swing over a microscope and an X-ray spectrometer to take a closer look. If the specimen warrants further analysis, Curiosity can drill into the boulder and deliver a powdered sample to either the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) or the CheMin analytical laboratories inside the rover.[85][86][87] The MastCam, Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI), and Mars Descent Imager (MARDI) cameras were developed by Malin Space Science Systems and they all share common design components, such as on-board digital image processing boxes, 1600 × 1200 charge-coupled device (CCDs), and an RGB Bayer pattern filter.[88][89][90][91][28][92]

In total, the rover carries 17 cameras: HazCams (8), NavCams (4), MastCams (2), MAHLI (1), MARDI (1), and ChemCam (1).[93]

Mast Camera (MastCam)[]

The MastCam system provides multiple spectra and true-color imaging with two cameras.[89] The cameras can take true-color images at 1600×1200 pixels and up to 10 frames per second hardware-compressed video at 720p (1280×720).[94]

One MastCam camera is the Medium Angle Camera (MAC), which has a 34 mm (1.3 in) focal length, a 15° field of view, and can yield 22 cm/pixel (8.7 in/pixel) scale at 1 km (0.62 mi). The other camera in the MastCam is the Narrow Angle Camera (NAC), which has a 100 mm (3.9 in) focal length, a 5.1° field of view, and can yield 7.4 cm/pixel (2.9 in/pixel) scale at 1 km (0.62 mi).[89] Malin also developed a pair of MastCams with zoom lenses,[95] but these were not included in the rover because of the time required to test the new hardware and the looming November 2011 launch date.[96] However, the improved zoom version was selected to be incorporated on the Mars 2020 mission as Mastcam-Z.[97]

Each camera has eight gigabytes of flash memory, which is capable of storing over 5,500 raw images, and can apply real time lossless data compression.[89] The cameras have an autofocus capability that allows them to focus on objects from 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) to infinity.[28] In addition to the fixed RGBG Bayer pattern filter, each camera has an eight-position filter wheel. While the Bayer filter reduces visible light throughput, all three colors are mostly transparent at wavelengths longer than 700 nm, and have minimal effect on such infrared observations.[89]

Chemistry and Camera complex (ChemCam)[]

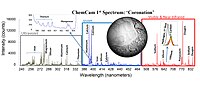

ChemCam is a suite of two remote sensing instruments combined as one: a laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) and a Remote Micro Imager (RMI) telescope. The ChemCam instrument suite was developed by the French CESR laboratory and the Los Alamos National Laboratory.[98][99][100] The flight model of the mast unit was delivered from the French CNES to Los Alamos National Laboratory.[101] The purpose of the LIBS instrument is to provide elemental compositions of rock and soil, while the RMI gives ChemCam scientists high-resolution images of the sampling areas of the rocks and soil that LIBS targets.[98][102] The LIBS instrument can target a rock or soil sample up to 7 m (23 ft) away, vaporizing a small amount of it with about 50 to 75 5-nanosecond pulses from a 1067 nm infrared laser and then observes the spectrum of the light emitted by the vaporized rock.[103]

ChemCam has the ability to record up to 6,144 different wavelengths of ultraviolet, visible, and infrared light.[104] Detection of the ball of luminous plasma is done in the visible, near-UV and near-infrared ranges, between 240 nm and 800 nm.[98] The first initial laser testing of the ChemCam by Curiosity on Mars was performed on a rock, N165 ("Coronation" rock), near Bradbury Landing on 19 August 2012.[105][106][107] The ChemCam team expects to take approximately one dozen compositional measurements of rocks per day.[108] Using the same collection optics, the RMI provides context images of the LIBS analysis spots. The RMI resolves 1 mm (0.039 in) objects at 10 m (33 ft) distance, and has a field of view covering 20 cm (7.9 in) at that distance.[98]

[]

The rover has two pairs of black and white navigation cameras mounted on the mast to support ground navigation.[109][110] The cameras have a 45° angle of view and use visible light to capture stereoscopic 3-D imagery.[110][111]

Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS)[]

REMS comprises instruments to measure the Mars environment: humidity, pressure, temperatures, wind speeds, and ultraviolet radiation.[112] It is a meteorological package that includes an ultraviolet sensor provided by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science. The investigative team is led by Javier Gómez-Elvira of the Spanish Astrobiology Center and includes the Finnish Meteorological Institute as a partner.[113][114] All sensors are located around three elements: two booms attached to the rover's mast, the Ultraviolet Sensor (UVS) assembly located on the rover top deck, and the Instrument Control Unit (ICU) inside the rover body. REMS provides new clues about the Martian general circulation, micro scale weather systems, local hydrological cycle, destructive potential of UV radiation, and subsurface habitability based on ground-atmosphere interaction.[113]

Hazard avoidance cameras (hazcams)[]

The rover has four pairs of black and white navigation cameras called hazcams, two pairs in the front and two pairs in the back.[109][115] They are used for autonomous hazard avoidance during rover drives and for safe positioning of the robotic arm on rocks and soils.[115] Each camera in a pair is hardlinked to one of two identical main computers for redundancy; only four out of the eight cameras are in use at any one time. The cameras use visible light to capture stereoscopic three-dimensional (3-D) imagery.[115] The cameras have a 120° field of view and map the terrain at up to 3 m (9.8 ft) in front of the rover.[115] This imagery safeguards against the rover crashing into unexpected obstacles, and works in tandem with software that allows the rover to make its own safety choices.[115]

Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI)[]

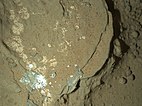

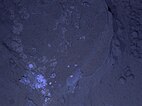

MAHLI is a camera on the rover's robotic arm, and acquires microscopic images of rock and soil. MAHLI can take true-color images at 1600×1200 pixels with a resolution as high as 14.5 µm per pixel. MAHLI has an 18.3 to 21.3 mm (0.72 to 0.84 in) focal length and a 33.8–38.5° field of view.[90] MAHLI has both white and ultraviolet Light-emitting diode (LED) illumination for imaging in darkness or fluorescence imaging. MAHLI also has mechanical focusing in a range from infinite to millimeter distances.[90] This system can make some images with focus stacking processing.[116] MAHLI can store either the raw images or do real time lossless predictive or JPEG compression. The calibration target for MAHLI includes color references, a metric bar graphic, a 1909 VDB Lincoln penny, and a stair-step pattern for depth calibration.[117]

Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS)[]

The APXS instrument irradiates samples with alpha particles and maps the spectra of X-rays that are re-emitted for determining the elemental composition of samples.[118] Curiosity's APXS was developed by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).[118] MacDonald Dettwiler (MDA), the Canadian aerospace company that built the Canadarm and RADARSAT, were responsible for the engineering design and building of the APXS. The APXS science team includes members from the University of Guelph, the University of New Brunswick, the University of Western Ontario, NASA, the University of California, San Diego and Cornell University.[119] The APXS instrument takes advantage of particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE) and X-ray fluorescence, previously exploited by the Mars Pathfinder and the two Mars Exploration Rovers.[118][120]

Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin)[]

CheMin is the Chemistry and Mineralogy X-ray powder diffraction and fluorescence instrument.[122] CheMin is one of four spectrometers. It can identify and quantify the abundance of the minerals on Mars. It was developed by David Blake at NASA Ames Research Center and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory,[123] and won the 2013 NASA Government Invention of the year award.[124] The rover can drill samples from rocks and the resulting fine powder is poured into the instrument via a sample inlet tube on the top of the vehicle. A beam of X-rays is then directed at the powder and the crystal structure of the minerals deflects it at characteristic angles, allowing scientists to identify the minerals being analyzed.[125]

On 17 October 2012, at "Rocknest", the first X-ray diffraction analysis of Martian soil was performed. The results revealed the presence of several minerals, including feldspar, pyroxenes and olivine, and suggested that the Martian soil in the sample was similar to the "weathered basaltic soils" of Hawaiian volcanoes.[121] The paragonetic tephra from a Hawaiian cinder cone has been mined to create Martian regolith simulant for researchers to use since 1998.[126][127]

Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM)[]

The SAM instrument suite analyzes organics and gases from both atmospheric and solid samples. It consists of instruments developed by the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, the Laboratoire Inter-Universitaire des Systèmes Atmosphériques (LISA) (jointly operated by France's CNRS and Parisian universities), and Honeybee Robotics, along with many additional external partners.[86][128][129] The three main instruments are a Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (QMS), a gas chromatograph (GC) and a tunable laser spectrometer (TLS). These instruments perform precision measurements of oxygen and carbon isotope ratios in carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) in the atmosphere of Mars in order to distinguish between their geochemical or biological origin.[86][129][130][131][132]

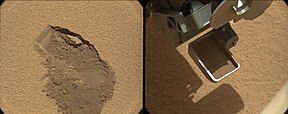

Dust Removal Tool (DRT)[]

The Dust Removal Tool (DRT) is a motorized, wire-bristle brush on the turret at the end of Curiosity's arm. The DRT was first used on a rock target named Ekwir_1 on 6 January 2013. Honeybee Robotics built the DRT.[133]

Radiation assessment detector (RAD)[]

The role of the Radiation assessment detector (RAD) instrument is to characterize the broad spectrum of radiation environment found inside the spacecraft during the cruise phase and while on Mars. These measurements have never been done before from the inside of a spacecraft in interplanetary space. Its primary purpose is to determine the viability and shielding needs for potential human explorers, as well as to characterize the radiation environment on the surface of Mars, which it started doing immediately after MSL landed in August 2012.[134] Funded by the Exploration Systems Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters and Germany's Space Agency (DLR), RAD was developed by Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) and the extraterrestrial physics group at Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Germany.[134][135]

Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN)[]

The DAN instrument employs a neutron source and detector for measuring the quantity and depth of hydrogen or ice and water at or near the Martian surface.[136] The instrument consists of the detector element (DE) and a 14.1 MeV pulsing neutron generator (PNG). The die-away time of neutrons is measured by the DE after each neutron pulse from the PNG. DAN was provided by the Russian Federal Space Agency[137][138] and funded by Russia.[139]

Mars Descent Imager (MARDI)[]

MARDI is fixed to the lower front left corner of the body of Curiosity. During the descent to the Martian surface, MARDI took color images at 1600×1200 pixels with a 1.3-millisecond exposure time starting at distances of about 3.7 km (2.3 mi) to near 5 m (16 ft) from the ground, at a rate of four frames per second for about two minutes.[91][140] MARDI has a pixel scale of 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) at 2 km (1.2 mi) to 1.5 mm (0.059 in) at 2 m (6 ft 7 in) and has a 90° circular field of view. MARDI has eight gigabytes of internal buffer memory that is capable of storing over 4,000 raw images. MARDI imaging allowed the mapping of surrounding terrain and the location of landing.[91] JunoCam, built for the Juno spacecraft, is based on MARDI.[141]

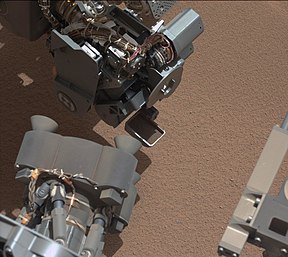

Robotic arm[]

The rover has a 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) long robotic arm with a cross-shaped turret holding five devices that can spin through a 350° turning range.[143][144] The arm makes use of three joints to extend it forward and to stow it again while driving. It has a mass of 30 kg (66 lb) and its diameter, including the tools mounted on it, is about 60 cm (24 in).[145] It was designed, built, and tested by MDA US Systems, building upon their prior robotic arm work on the Mars Surveyor 2001 Lander, the Phoenix lander, and the two Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity.[146]

Two of the five devices are in-situ or contact instruments known as the X-ray spectrometer (APXS), and the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI camera). The remaining three are associated with sample acquisition and sample preparation functions: a percussion drill; a brush; and mechanisms for scooping, sieving, and portioning samples of powdered rock and soil.[143][145] The diameter of the hole in a rock after drilling is 1.6 cm (0.63 in) and up to 5 cm (2.0 in) deep.[144][147] The drill carries two spare bits.[147][148] The rover's arm and turret system can place the APXS and MAHLI on their respective targets, and also obtain powdered sample from rock interiors, and deliver them to the SAM and CheMin analyzers inside the rover.[144]

Since early 2015 the percussive mechanism in the drill that helps chisel into rock has had an intermittent electrical short.[149] On 1 December 2016, the motor inside the drill caused a malfunction that prevented the rover from moving its robotic arm and driving to another location.[150] The fault was isolated to the drill feed brake,[151] and internal debris is suspected of causing the problem.[149] By 9 December 2016, driving and robotic arm operations were cleared to continue, but drilling remained suspended indefinitely.[152] The Curiosity team continued to perform diagnostics and testing on the drill mechanism throughout 2017,[153] and resumed drilling operations on 22 May 2018.[154]

Media, cultural impact and legacy[]

Live video showing the first footage from the surface of Mars was available at NASA TV, during the late hours of 6 August 2012 PDT, including interviews with the mission team. The NASA website momentarily became unavailable from the overwhelming number of people visiting it,[155] and a 13-minute NASA excerpt of the landings on its YouTube channel was halted an hour after the landing by an automated DMCA takedown notice from Scripps Local News, which prevented access for several hours.[156] Around 1,000 people gathered in New York City's Times Square, to watch NASA's live broadcast of Curiosity's landing, as footage was being shown on the giant screen.[157] Bobak Ferdowsi, Flight Director for the landing, became an Internet meme and attained Twitter celebrity status, with 45,000 new followers subscribing to his Twitter account, due to his Mohawk hairstyle with yellow stars that he wore during the televised broadcast.[158][159]

On 13 August 2012, U.S. President Barack Obama, calling from aboard Air Force One to congratulate the Curiosity team, said, "You guys are examples of American know-how and ingenuity. It's really an amazing accomplishment".[160] (Video (07:20))

Scientists at the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles, California, viewed the CheMin instrument aboard Curiosity as a potentially valuable means to examine ancient works of art without damaging them. Until recently, only a few instruments were available to determine the composition without cutting out physical samples large enough to potentially damage the artifacts. CheMin directs a beam of X-rays at particles as small as 400 μm (0.016 in)[161] and reads the radiation scattered back to determine the composition of the artifact in minutes. Engineers created a smaller, portable version named the X-Duetto. Fitting into a few briefcase-sized boxes, it can examine objects on site, while preserving their physical integrity. It is now being used by Getty scientists to analyze a large collection of museum antiques and the Roman ruins of Herculaneum, Italy.[162]

Prior to the landing, NASA and Microsoft released Mars Rover Landing, a free downloadable game on Xbox Live that uses Kinect to capture body motions, which allows users to simulate the landing sequence.[163]

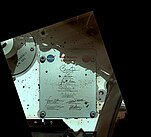

NASA gave the general public the opportunity from 2009 until 2011 to submit their names to be sent to Mars. More than 1.2 million people from the international community participated, and their names were etched into silicon using an electron-beam machine used for fabricating micro devices at JPL, and this plaque is now installed on the deck of Curiosity.[164] In keeping with a 40-year tradition, a plaque with the signatures of President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden was also installed. Elsewhere on the rover is the autograph of Clara Ma, the 12-year-old girl from Kansas who gave Curiosity its name in an essay contest, writing in part that "curiosity is the passion that drives us through our everyday lives".[165]

On 6 August 2013, Curiosity audibly played "Happy Birthday to You" in honor of the one Earth year mark of its Martian landing, the first time for a song to be played on another planet. This was also the first time music was transmitted between two planets.[166]

On 24 June 2014, Curiosity completed a Martian year — 687 Earth days — after finding that Mars once had environmental conditions favorable for microbial life.[167] Curiosity served as the basis for the design of the Perseverance rover for the Mars 2020 rover mission. Some spare parts from the build and ground test of Curiosity are being used in the new vehicle, but it will carry a different instrument payload.[168]

On 5 August 2017, NASA celebrated the fifth anniversary of the Curiosity rover mission landing, and related exploratory accomplishments, on the planet Mars.[15][16] (Videos: Curiosity's First Five Years (02:07); Curiosity's POV: Five Years Driving (05:49); Curiosity's Discoveries About Gale Crater (02:54))

As reported in 2018, drill samples taken in 2015 uncovered organic molecules of benzene and propane in 3 billion year old rock samples in Gale.[169][170][171]

Images[]

Components of Curiosity[]

Mast head with ChemCam, MastCam-34, MastCam-100, NavCam.

One of the six wheels on Curiosity

High-gain (right) and low-gain (left) antennas

UV sensor

Orbital images[]

Curiosity descending under its parachute (6 August 2012; MRO/HiRISE).

Curiosity's parachute flapping in Martian wind (12 August 2012 to 13 January 2013; MRO).

Gale crater - surface materials (false colors; THEMIS; 2001 Mars Odyssey).

Curiosity's landing site is on Aeolis Palus near Mount Sharp (north is down).

Mount Sharp rises from the middle of Gale; the green dot marks Curiosity's landing site (north is down).

Green dot is Curiosity's landing site; upper blue is Glenelg; lower blue is base of Mount Sharp.

Curiosity's landing ellipse. Quad 51, called Yellowknife, marks the area where Curiosity actually landed.

Quad 51, a 1-mile-by-1-mile section of the crater Gale - Curiosity landing site is noted.

Curiosity's landing site, Bradbury Landing, as seen by MRO/HiRISE (14 August 2012)

Curiosity's first tracks viewed by MRO/HiRISE (6 September 2012)

Rover images[]

Ejected heat shield as viewed by Curiosity descending to Martian surface (6 August 2012).

Curiosity's first image after landing (6 August 2012). The rover's wheel can be seen.

Curiosity's first image after landing (without clear dust cover, 6 August 2012)

Curiosity landed on 6 August 2012 near the base of Aeolis Mons (or "Mount Sharp")[172]

Curiosity's first color image of the Martian landscape, taken by MAHLI (6 August 2012)

Curiosity's self-portrait - with closed dust cover (7 September 2012)

Curiosity's self-portrait (7 September 2012; color-corrected)

Calibration target of MAHLI (9 September 2012; alternate 3-D version)

U.S. Lincoln penny on Mars (Curiosity; 10 September 2012)

(3-D; 2 October 2013)

U.S. Lincoln penny on Mars (Curiosity; 4 September 2018)

Curiosity's tracks on first test drive (22 August 2012), after parking 6 m (20 ft) from original landing site[10]

Comparison of color versions (raw, natural, white balance) of Aeolis Mons on Mars (23 August 2012)

Curiosity's view of Aeolis Mons (9 August 2012; white-balanced image)

Layers at the base of Aeolis Mons. The dark rock in inset is the same size as Curiosity.

Self-portraits[]

(October 2012)

(May 2013)

(May 2014)

(January 2015)

(August 2015)

(October 2015)

(January 2016)

(September 2016)

(January 2018)

(June 2018)

(January 2019)

(May 2019)

(October 2019)

(March 2021)

Wide images[]

See also[]

- Experience Curiosity

- InSight – Mars lander, arrived November 2018

- Life on Mars – Scientific assessments on the microbial habitability of Mars

- Viking program – Pair of NASA landers and orbiters sent to Mars in 1976

- Timeline of Mars Science Laboratory

- Mars Express

- 2001 Mars Odyssey

- Mars Orbiter Mission – Indian Mars orbiter, launched in 2013

- Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

- Mars 2020 – Astrobiology Mars rover mission by NASA

- Sojourner (rover)

- Spirit (rover)

- Opportunity (rover)

- Perseverance (rover)

- Rosalind Franklin (rover)

- Zhurong (rover)

References[]

- ^ "Rover Fast Facts". NASA. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nelson, Jon. "Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity Rover". NASA. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ "Curiosity: NASA's Next Mars Rover". NASA. 6 August 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Beutel, Allard (19 November 2011). "NASA's Mars Science Laboratory Launch Rescheduled for Nov. 26". NASA. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Abilleira, Fernando (2013). 2011 Mars Science Laboratory Trajectory Reconstruction and Performance from Launch Through Landing. 23rd AAS/AIAA Spaceflight Mechanics Meeting. February 10–14, 2013. Kauai, Hawaii.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Amos, Jonathan (8 August 2012). "Nasa's Curiosity rover lifts its navigation cameras". BBC News. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Wall, Mike (6 August 2012). "Touchdown! Huge NASA Rover Lands on Mars". Space.com. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ "Where Is Curiosity?". mars.nasa.gov. NASA. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "MSL Sol 3 Update". NASA Television. 8 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brown, Dwayne; Cole, Steve; Webster, Guy; Agle, D.C. (22 August 2012). "NASA Mars Rover Begins Driving at Bradbury Landing". NASA. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Impressive' Curiosity landing only 1.5 miles off, NASA says". CNN. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Overview". JPL, NASA. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Mars Science Laboratory: Mission Science Goals". NASA. August 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "Curiosity's mission extended indefinitely". Newshub. 5 December 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Webster, Guy; Cantillo, Laurie; Brown, Dwayne (2 August 2017). "Five Years Ago and 154 Million Miles Away: Touchdown!". NASA. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wall, Mike (5 August 2017). "After 5 Years on Mars, NASA's Curiosity Rover Is Still Making Big Discoveries". Space.com. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ Bosco, Cassandro (12 March 2013). "NASA/JPL Mars Curiosity Project Team Receive 2012 Robert J. Collier Trophy" (PDF). National Aeronautic Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ "MSL Objectives". NASA.

- ^ Phillips, Tony (24 February 2012). "Curiosity, The Stunt Double". NASA. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ Grotzinger, John P. (24 January 2014). "Habitability, Taphonomy, and the Search for Organic Carbon on Mars". Science. 343 (6169): 386–387. Bibcode:2014Sci...343..386G. doi:10.1126/science.1249944. PMID 24458635.

- ^ "PIA16068". NASA.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brown, Dwayne C.; Buis, Alan; Martinez, Carolina (27 May 2009). "NASA Selects Student's Entry as New Mars Rover Name". NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Dreier, Casey (29 July 2020). "The Cost of Perseverance, in Context". The Planetary Society.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "MSL at a glance". CNES. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Watson, Traci (14 April 2008). "Troubles parallel ambitions in NASA Mars project". USA Today. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ^ Mars Rovers: Pathfinder, MER (Spirit and Opportunity), and MSL (video). Pasadena, California. 12 April 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ "Mars Exploration Rover Launches" (PDF). NASA. June 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Mars Science Laboratory (MSL): Mast Camera (MastCam): Instrument Description". Malin Space Science Systems. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Mars Science Laboratory - Facts" (PDF). Jet Propulsion Laboratory, NASA. March 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Makovsky, Andre; Ilott, Peter; Taylor, Jim (November 2009). Mars Science Laboratory Telecommunications System Design (PDF). DESCANSO Design and Performance Summary Series. 14. NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG)" (PDF). NASA/JPL. October 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Mars Exploration: Radioisotope Power and Heating for Mars Surface Exploration" (PDF). NASA/JPL. 18 April 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (17 November 2011). "Nuclear power generator hooked up to Mars rover". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Ritz, Fred; Peterson, Craig E. (2004). Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG) Program Overview (PDF). 2004 IEEE Aerospace Conference. March 6–13, 2004. Big Sky, Montana. doi:10.1109/AERO.2004.1368101. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2011.

- ^ Campbell, Joseph (2011). "Fueling the Mars Science Laboratory" (PDF). Idaho National Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ "Technologies of Broad Benefit: Power". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 14 June 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory – Technologies of Broad Benefit: Power". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ Misra, Ajay K. (26 June 2006). "Overview of NASA Program on Development of Radioisotope Power Systems with High Specific Power" (PDF). NASA/JPL. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Watanabe, Susan (9 August 2009). "Keeping it Cool (...or Warm!)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Mars Science Laboratory: Mission: Rover: Brains". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ Bajracharya, Max; Maimone, Mark W.; Helmick, Daniel (December 2008). "Autonomy for Mars rovers: past, present, and future". Computer. 41 (12): 45. doi:10.1109/MC.2008.515. ISSN 0018-9162.

- ^ "BAE Systems Computers to Manage Data Processing and Command For Upcoming Satellite Missions" (Press release). SpaceDaily. 17 June 2008.

- ^ "E&ISNow — Media gets closer look at Manassas" (PDF). BAE Systems. 1 August 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ^ "RAD750 radiation-hardened PowerPC microprocessor". BAE Systems. 1 July 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ "RAD6000 Space Computers" (PDF). BAE Systems. 23 June 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ Webster, Guy (4 March 2013). "Curiosity Rover's Recovery on Track". NASA. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ Webster, Guy (25 March 2013). "Curiosity Resumes Science Investigations". NASA. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Gaudin, Sharon (8 August 2012). "NASA: Your smartphone is as smart as the Curiosity rover". Computerworld. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ "Mars-Earth distance in light minutes". WolframAlpha. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ "Curiosity's data communication with Earth". NASA. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ "NASA's Curiosity Rover Maximizes Data Sent to Earth by Using International Space Data Communication Standards" (PDF). Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "ESA spacecraft records crucial NASA signals from Mars". Mars Daily. 7 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ NASA Mars exploration efforts turn to operating existing missions and planning sample return. Jeff Foust, Space News. 23 February 2018.

- ^ "Next Mars Rover Sports a Set of New Wheels". NASA/JPL. July 2010.

- ^ "Watch NASA's Next Mars Rover Being Built Via Live 'Curiosity Cam'". NASA. 13 September 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ "New Mars Rover to Feature Morse Code". National Association for Amateur Radio.

- ^ Marlow, Jeffrey (29 August 2012). "Looking Toward the Open Road". JPL - Martian Diaries. NASA. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (19 August 2014). "Curiosity wheel damage: The problem and solutions". The Planetary Society Blogs. The Planetary Society. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ "First drive".

- ^ Gorman, Steve (8 August 2011). "Curiosity beams Mars images back". Stuff - Science. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mars Science Laboratory". NASA. Archived from the original on July 30, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ "Vandi Verma". ResearchGate. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Dr. Vandi Verma Group Supervisor". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. CIT. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Estlin, Tara; Jonsson, Ari; Pasareanu, Carina; Simmons, Reid; Tso, Kam; Verma, Vandi. "Plan Execution Interchange Language (PLEXIL)" (PDF). NASA Technical Reports Server. NASA. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Bibliography of PLEXIL-related publications, organized by category". plexil,souceforge. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "Main page: NASA applications". plexil.sourceforge. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "Curiosity's Quad - IMAGE". NASA. 10 August 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ Agle, DC; Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (9 August 2012). "NASA's Curiosity Beams Back a Color 360 of Gale Crate". NASA. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (9 August 2012). "Mars rover makes first colour panorama". BBC News. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Halvorson, Todd (9 August 2012). "Quad 51: Name of Mars base evokes rich parallels on Earth". USA Today. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ "Video from rover looks down on Mars during landing". MSNBC. 6 August 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ Young, Monica (7 August 2012). "Watch Curiosity Descend onto Mars". SkyandTelescope.com. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ Hand, Eric (3 August 2012). "Crater mound a prize and puzzle for Mars rover". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11122. S2CID 211728989. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ "Gale Crater's History Book". Mars Odyssey THEMIS. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (5 October 2015). "Mars Is Pretty Clean. Her Job at NASA Is to Keep It That Way". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ "Why NASA's Mars Curiosity Rover landing will be "Seven Minutes of Absolute Terror"". NASA. Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES). 28 June 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Final Minutes of Curiosity's Arrival at Mars". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ Teitel, Amy Shira (28 November 2011). "Sky Crane – how to land Curiosity on the surface of Mars". Scientific American. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Snider, Mike (17 July 2012). "Mars rover lands on Xbox Live". USA Today. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory: Entry, Descent, and Landing System Performance" (PDF). NASA. March 2006. p. 7.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (12 June 2012). "NASA's Curiosity rover targets smaller landing zone". BBC News. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ "MSL Notebook - Curiosity Mars Rover data". an.rsl.wustl.edu. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ Amanda Kooser (5 September 2020). "NASA's Perseverance Mars rover has an Earth twin named Optimism". C/Net.

- ^ Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) (4 September 2020). "NASA Readies Perseverance Mars Rover's Earthly Twin". Mars Exploration Program. NASA.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (3 August 2012). "Gale Crater: Geological 'sweet shop' awaits Mars rover". BBC News. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "MSL Science Corner: Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM)". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ "Overview of the SAM instrument suite". NASA. Archived from the original on 22 February 2007.

- ^ Malin, M. C.; Bell, J. F.; Cameron, J.; Dietrich, W. E.; Edgett, K. S.; et al. (2005). The Mast Cameras and Mars Descent Imager (MARDI) for the 2009 Mars Science Laboratory (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVI. p. 1214. Bibcode:2005LPI....36.1214M.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Mast Camera (MastCam)". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 18 February 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI)". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Mars Descent Imager (MARDI)". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ^ Stern, Alan; Green, Jim (8 November 2007). "Mars Science Laboratory Instrumentation Announcement from Alan Stern and Jim Green, NASA Headquarters". SpaceRef.com. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Mann, Adam (7 August 2012). "The Photo-Geek's Guide to Curiosity Rover's 17 Cameras". Wired. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Klinger, Dave (7 August 2012). "Curiosity says good morning from Mars (and has busy days ahead)". Ars Technica. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) Mast Camera (MastCam)". Malin Space Science Systems. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ David, Leonard (28 March 2011). "NASA Nixes 3-D Camera for Next Mars Rover". Space.com. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Bell III, J. F.; Maki, J. N.; Mehall, G. L.; Ravine, M. A.; Caplinger, M. A. (2014). Mastcam-Z: A Geologic, Stereoscopic, and Multispectral Investigation on the NASA Mars-2020 Rover (PDF). International Workshop on Instrumentation for Planetary Missions, 4–7 November 2014, Greenbelt, Maryland. NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "MSL Science Corner: Chemistry & Camera (ChemCam)". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ Salle, B.; Lacour, J. L.; Mauchien, P.; Fichet, P.; Maurice, S.; et al. (2006). "Comparative study of different methodologies for quantitative rock analysis by Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy in a simulated Martian atmosphere" (PDF). Spectrochimica Acta Part B: Atomic Spectroscopy. 61 (3): 301–313. Bibcode:2006AcSpe..61..301S. doi:10.1016/j.sab.2006.02.003.

- ^ Wiens, R.C.; Maurice, S.; Engel, A; Fabry, V. J.; Hutchins, D. A.; et al. (2008). "Corrections and Clarifications, News of the Week". Science. 322 (5907): 1466. doi:10.1126/science.322.5907.1466a. PMC 1240923.

- ^ "ChemCam Status". Los Alamos National Laboratory. April 2008. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ "Spacecraft: Surface Operations Configuration: Science Instruments: ChemCam". Archived from the original on 2 October 2006.

- ^ Vieru, Tudor (6 December 2013). "Curiosity's Laser Reaches 100,000 Firings on Mars". Softpedia. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Rover's Laser Instrument Zaps First Martian Rock". 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Webster, Guy; Agle, D.C. (19 August 2012). "Mars Science Laboratory/Curiosity Mission Status Report". NASA. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ "'Coronation' Rock on Mars". NASA. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (17 August 2012). "Nasa's Curiosity rover prepares to zap Martian rocks". BBC News. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ "How Does ChemCam Work?". ChemCam Team. 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mars Science Laboratory Rover in the JPL Mars Yard". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 10 May 2009. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ^ "First NavCam mosaic".

- ^ Gómez-Elvira, J.; Haberle, B.; Harri, A.; Martinez-Frias, J.; Renno, N.; Ramos, M.; Richardson, M.; de la Torre, M.; Alves, J.; Armiens, C.; Gómez, F.; Lepinette, A.; Mora, L.; Martín, J.; Martín-Torres, J.; Navarro, S.; Peinado, V.; Rodríguez-Manfredi, J. A.; Romeral, J.; Sebastián, E.; Torres, J.; Zorzano, M. P.; Urquí, R.; Moreno, J.; Serrano, J.; Castañer, L.; Jiménez, V.; Genzer, M.; Polko, J. (February 2011). "Rover Environmental Monitoring Station for MSL mission" (PDF). 4th International Workshop on the Mars Atmosphere: Modelling and Observations: 473. Bibcode:2011mamo.conf..473G. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "MSL Science Corner: Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS)". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory Fact Sheet" (PDF). NASA/JPL. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Mars Science Laboratory: Mission: Rover: Eyes and Other Senses: Four Engineering Hazcams (Hazard Avoidance Cameras)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ Edgett, Kenneth S. "Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI)". NASA. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2012.

- ^ "3D View of MAHLI Calibration Target". NASA. 13 September 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "MSL Science Corner: Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS)". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ "40th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference" (PDF). 2009.

"41st Lunar and Planetary Science Conference" (PDF). 2010. - ^ Rieder, R.; Gellert, R.; Brückner, J.; Klingelhöfer, G.; Dreibus, G.; et al. (2003). "The new Athena alpha particle X-ray spectrometer for the Mars Exploration Rovers". Journal of Geophysical Research. 108 (E12): 8066. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.8066R. doi:10.1029/2003JE002150.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brown, Dwayne (30 October 2012). "NASA Rover's First Soil Studies Help Fingerprint Martian Minerals". NASA. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ "MSL Chemistry & Mineralogy X-ray diffraction(CheMin)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ Sarrazin, P.; Blake, D.; Feldman, S.; Chipera, S.; Vaniman, D.; et al. (2005). "Field deployment of a portable X-ray diffraction/X-ray fluorescence instrument on Mars analog terrain". Powder Diffraction. 20 (2): 128–133. Bibcode:2005PDiff..20..128S. doi:10.1154/1.1913719.

- ^ Hoover, Rachel (24 June 2014). "Ames Instrument Helps Identify the First Habitable Environment on Mars, Wins Invention Award". NASA. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ^ Anderson, Robert C.; Baker, Charles J.; Barry, Robert; Blake, David F.; Conrad, Pamela; et al. (14 December 2010). "Mars Science Laboratory Participating Scientists Program Proposal Information Package" (PDF). NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Beegle, L. W.; Peters, G. H.; Mungas, G. S.; Bearman, G. H.; Smith, J. A.; et al. (2007). "Mojave Martian Simulant: A New Martian Soil Simulant" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (1338): 2005. Bibcode:2007LPI....38.2005B. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ Allen, C. C.; Morris, R. V.; Lindstrom, D. J.; Lindstrom, M. M.; Lockwood, J. P. (March 1997). JSC Mars-1: Martian regolith simulant (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Exploration XXVIII. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ Cabane, M.; Coll, P.; Szopa, C.; Israël, G.; Raulin, F.; et al. (2004). "Did life exist on Mars? Search for organic and inorganic signatures, one of the goals for "SAM" (sample analysis at Mars)" (PDF). Advances in Space Research. 33 (12): 2240–2245. Bibcode:2004AdSpR..33.2240C. doi:10.1016/S0273-1177(03)00523-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) Instrument Suite". NASA. October 2008. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ Tenenbaum, D. (9 June 2008). "Making Sense of Mars Methane". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ Tarsitano, C. G.; Webster, C. R. (2007). "Multilaser Herriott cell for planetary tunable laser spectrometers". Applied Optics. 46 (28): 6923–6935. Bibcode:2007ApOpt..46.6923T. doi:10.1364/AO.46.006923. PMID 17906720.

- ^ Mahaffy, Paul R.; Webster, Christopher R.; Cabane, Michel; Conrad, Pamela G.; Coll, Patrice; et al. (2012). "The Sample Analysis at Mars Investigation and Instrument Suite". Space Science Reviews. 170 (1–4): 401–478. Bibcode:2012SSRv..170..401M. doi:10.1007/s11214-012-9879-z. S2CID 3759945.

- ^ Moskowitz, Clara (7 January 2013). "NASA's Curiosity Rover Brushes Mars Rock Clean, a First". Space.com. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "SwRI Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) Homepage". Southwest Research Institute. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ "RAD". NASA.

- ^ "Laboratory for Space Gamma Spectroscopy - DAN". Laboratory for Space Gamma Spectroscopy. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ "MSL Science Corner: Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN)". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ^ Litvak, M. L.; Mitrofanov, I. G.; Barmakov, Yu. N.; Behar, A.; Bitulev, A.; et al. (2008). "The Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) Experiment for NASA's 2009 Mars Science Laboratory". Astrobiology. 8 (3): 605–12. Bibcode:2008AsBio...8..605L. doi:10.1089/ast.2007.0157. PMID 18598140.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory: Mission". NASA JPL. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ "Mars Descent Imager (MARDI) Update". Malin Space Science Systems. 12 November 2007. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ "Junocam, Juno Jupiter Orbiter". Malin Space Science Systems. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Anderson, Paul Scott (3 February 2013). "Curiosity 'hammers' a rock and completes first drilling tests". themeridianijournal.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Curiosity Rover - Arm and Hand". JPL. NASA. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jandura, Louise. "Mars Science Laboratory Sample Acquisition, Sample Processing and Handling: Subsystem Design and Test Challenges" (PDF). JPL. NASA. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Curiosity Stretches its Arm". JPL. NASA. 21 August 2012. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ Billing, Rius; Fleischner, Richard. "Mars Science Laboratory Robotic Arm" (PDF). MDA US Systems. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b "MSL Participating Scientists Program - Proposal Information Package" (PDF). Washington University. 14 December 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ Billing, Rius; Fleischner, Richard (2011). "Mars Science Laboratory Robotic Arm" (PDF). 15th European Space Mechanisms and Tribology Symposium 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clark, Stephen (29 December 2016). "Internal debris may be causing problem with Mars rover's drill". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ "NASA Is Trying to Get Mars Rover Curiosity's Arm Unstuck". Popular Mechanics. Associated Press. 13 December 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ Wall, Mike (15 December 2016). "Drill Issue Continues to Afflict Mars Rover Curiosity". SPACE.com. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "Sols 1545-1547: Moving again!". NASA Mars Rover Curiosity: Mission Updates. NASA. 9 December 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (6 September 2017). "Curiosity's balky drill: The problem and solutions". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Curiosity Rover is Drilling Again David Dickinon, Sky and Telescope, 4 June 2018

- ^ "Curiosity Lands on Mars". NASA TV. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ "NASA's Mars Rover Crashed Into a DMCA Takedown". Motherboard. Motherboard.vice.com. 6 August 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Huge Crowds Watched NASA Rover Land on Mars from NYC's Times Square". Space.com. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Mars Rover 'Mohawk Guy' a Space Age Internet Sensation | Curiosity Rover". Space.com. 7 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Mars landing proves memes now travel faster than the speed of light (gallery)". VentureBeat. 18 June 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (13 August 2012). "Mars Looks Quite Familiar, if Only on the Surface". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ Boyer, Brad (10 March 2011). "inXitu co-founder wins NASA Invention of the Year Award for 2010" (PDF) (Press release). InXitu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ "Martian rover tech has an eye for priceless works of art". 10 August 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Thomen, Daryl (6 August 2012). "'Mars Rover Landing' with Kinect for the Xbox 360". Newsday. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Send Your Name to Mars". NASA. 2010. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ "NASA's Curiosity rover flying to Mars with Obama's, others' autographs on board". collectSPACE. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ Dewey, Caitlin (6 August 2013). "Lonely Curiosity rover sings 'Happy Birthday' to itself on Mars". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ^ Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (23 June 2014). "NASA's Mars Curiosity Rover Marks First Martian Year". NASA. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Harwood, William (4 December 2012). "NASA announces plans for new $1.5 billion Mars rover". CNET. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

Using spare parts and mission plans developed for NASA's Curiosity Mars rover, the space agency says it can build and launch a new rover in 2020 and stay within current budget guidelines.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (7 June 2018). "Life on Mars? Rover's Latest Discovery Puts It "On the Table"". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

The identification of organic molecules in rocks on the red planet does not necessarily point to life there, past or present, but does indicate that some of the building blocks were present.

- ^ Ten Kate, Inge Loes (8 June 2018). "Organic molecules on Mars". Science (journal). 360 (6393): 1068–1069. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1068T. doi:10.1126/science.aat2662. PMID 29880670. S2CID 46952468.

- ^ Eigenbrode, Jennifer L.; et al. (8 June 2018). "Organic matter preserved in 3-billion-year-old mudstones at Gale crater, Mars" (PDF). Science (journal). 360 (6393): 1096–1101. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1096E. doi:10.1126/science.aas9185. PMID 29880683. S2CID 46983230.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams, John (15 August 2012). "A 360-degree 'street view' from Mars". PhysOrg. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ Bodrov, Andrew (14 September 2012). "Mars Panorama - Curiosity rover: Martian solar day 2". 360Cities. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

External links[]

| Look up Curiosity in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

- Curiosity - NASA's Mars Exploration Program

- The search for life on Mars and elsewhere in the Solar System: Curiosity update - Video lecture by Christopher P. McKay

- MSL - Curiosity Design and Mars Landing - PBS Nova (14 November 2012) - Video (53:06)

- MSL - "Curiosity 'StreetView'" (Sol 2 - 8 August 2012) - NASA/JPL - 360° Panorama

- MSL - Curiosity Rover - Learn About Curiosity - NASA/JPL

- MSL - Curiosity Rover - Virtual Tour - NASA/JPL

- MSL - NASA Image Gallery

- Weather Reports from the Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS)

- Curiosity on Twitter

- MSL - NASA Update - AGU Conference (3 December 2012) Video (70:13)

- Panorama (via Universe Today)

- Curiosity's Proposed Path up Mount Sharp NASA May 2019

- 2011 robots

- 2012 on Mars

- Aeolis quadrangle

- American inventions

- Astrobiology space missions

- Individual space vehicles

- Mars rovers

- Mars Science Laboratory

- NASA space probes

- Nuclear-powered robots

- Nuclear power in space

- Robots of the United States

- Six-wheeled robots

- Soft landings on Mars

- Space probes launched in 2011