D.O.A. (1950 film)

| D.O.A. | |

|---|---|

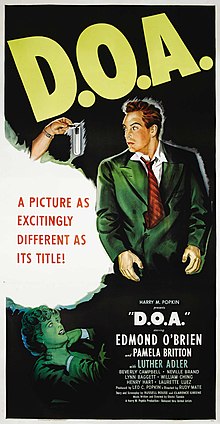

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Rudolph Maté |

| Written by | |

| Produced by | Leo C. Popkin |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Ernest Laszlo |

| Edited by | Arthur H. Nadel |

| Music by | Dimitri Tiomkin |

| Color process | Black and white |

Production companies | Harry Popkin Productions Cardinal Pictures |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 84 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

D.O.A. is a 1950 American film noir directed by Rudolph Maté, starring Edmond O'Brien and Pamela Britton. It is considered a classic of the genre. A fatally poisoned man tries to find out who has poisoned him and why. It was the film debuts of Beverly Garland (as Beverly Campbell) and Laurette Luez.

Leo C. Popkin produced D.O.A. for his short-lived Cardinal Pictures. Due to a filing error, the copyright to the film was not renewed on time,[1] causing it to fall into the public domain.

Plot[]

A long, behind-the-back tracking sequence features Frank Bigelow walking through the hallway of a police station to report his own murder. Oddly, the police have been expecting him and already know who he is.

A flashback begins with Bigelow in his hometown of Banning, California, where he is an accountant and notary public. He decides to take a one-week vacation in San Francisco, but this does not sit well with Paula Gibson, his confidential secretary and girlfriend, as he does not want her to accompany him.

Bigelow goes out to a nightclub; unnoticed, a stranger swaps his drink for another one.[a] The next morning, Bigelow feels ill. A doctor determines he swallowed a "luminous toxin" for which there is no antidote. Bigelow gets a second opinion, which confirms the fatal diagnosis. The second doctor states that the poisoning must have been deliberate. Bigelow remembers that his drink at the nightclub tasted strange.

With only a few days to live, Bigelow sets out to untangle the events behind his impending death, interrupted by occasional phone calls from Paula. She provides the first clue: a man named Eugene Phillips had been urgently trying to contact Bigelow for the last few days, but died suddenly. Bigelow travels to Phillips' import-export company in Los Angeles, first meeting Miss Foster, a secretary, and then Mr. Halliday, the comptroller, who tells him that Phillips committed suicide a day earlier. From there, the trail leads to Phillips' widow and his brother Stanley. He learns that Eugene had been arrested two days ago, but had made bail the next day. Six months earlier, he had sold some rare iridium, which turned out to be stolen, to a dealer named Majak. Eugene bought the iridium from George Reynolds, but two months ago he had grown suspicious that something was wrong. Bigelow had notarized the bill of sale. Phillips could have cleared himself with the bill, but it is missing. Philips thought George Reynolds took it, but was unable to find him.

In trying to find George Reynolds, Bigelow manages to connect Phillips' mistress to gangsters led by Majak. Bigelow is soon taken to Majak, where he learns that George Reynolds — actually Majak's nephew, Raymond Rakubian — died of poisoning about a month after the sale. Originally Majak had no reason to kill Bigelow, but now Bigelow knows too much. Majak orders his psychopathic henchman Chester to kill Bigelow, but Bigelow escapes, and Chester is killed by the police while attempting to kill Bigelow.

Bigelow now thinks Stanley Philips and Miss Foster are his killers, but when he confronts them, he finds out that Stanley has just been poisoned too. Stanley produces a letter found in Eugene's desk that very day by Miss Foster, a letter which proves that Halliday and Mrs. Phillips have been having an affair. Bigelow tells Miss Foster to call an ambulance, and to tell them what the poison is.

Upon confronting Mrs. Phillips, Bigelow learns that she originally diverted him with the theft of the iridium ... and that Eugene Philips died because he had discovered the affair and then quarreled with Halliday. Halliday threw him off a 6th floor balcony to make it look like Eugene committed suicide to avoid going to prison. However, when they discovered that there was evidence of his innocence, Halliday targeted Bigelow. Bigelow tracks Halliday to the Phillips company. Halliday is wearing the same distinctive coat and scarf as the man who switched the drinks. Halliday draws a gun and fires first, but Bigelow fatally shoots him.

The flashback ends. Bigelow finishes telling his story ... and dies, his last word being "Paula." The police detective taking down the report instructs that his file be marked "D.O.A."

Cast[]

|

Edmond O'Brien as Frank Bigelow |  |

Pamela Britton as Paula Gibson |

|

Luther Adler as Majak |  |

Lynn Baggett as Mrs. Phillips |

|

William Ching as Halliday |  |

Henry Hart as Stanley Phillips |

|

Beverly Garland (credited Beverly Campbell) as Miss Foster |  |

Neville Brand as Chester |

|

Laurette Luez as Marla Rakubian |  |

Virginia Lee as Jeannie |

Additional cast members:

- Jess Kirkpatrick as Sam

- Cay Forrester as Sue

- Frank Jaquet as Dr. Matson

- Lawrence Dobkin as Dr. Schaefer

- Frank Gerstle as Dr. MacDonald

- Carol Hughes as Kitty

- Frank Cady as Eddie the bartender in Banning (uncredited)

- Michael Ross as Dave the bartender in San Francisco

- Donna Sanborn as the nurse

Reception[]

Critical reception[]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 88% based on reviews from 25 critics.[2]

The New York Times, in its May 1950 review, described it as a "fairly obvious and plodding recital, involving crime, passion, stolen iridium, gangland beatings and one man's innocent bewilderment upon being caught up in a web of circumstance that marks him for death". O'Brien's performance had a "good deal of drive", while Britton adds a "pleasant touch of blonde attractiveness".[3]

In 1981 Foster Hirsch carried on a trend of more positive reviews, calling Bigelow's search for his own killer noir irony at its blackest. He wrote, "One of the film's many ironies is that his last desperate search involves him in his life more forcefully than he has ever been before... Tracking down his killer just before he dies — discovering the reason for his death — turns out to be the triumph of his life."[4] Critic A. K. Rode notes Rudolph Maté's technical background, writing:

D.O.A. reflects the photographic roots of director Rudolph Maté. He compiled an impressive resume as a cinematographer in Hollywood from 1935 (Dante's Inferno, Stella Dallas, The Adventures of Marco Polo, Foreign Correspondent, Pride of the Yankees, and Gilda, among others) until turning to directing in 1947. The lighting, locations, and atmosphere of brooding darkness were captured expertly by Mate and director of photography Ernest Lazlo.[5]

David Wood of the BBC described the opening as "perhaps one of cinema's most innovative opening sequences."[6] Michael Sragow, in a Salon web review (2000) of a DVD release of the film, characterized it as a "high-concept movie before its time."[7] Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide (2008) gave D.O.A. 3½ stars (out of 4).[citation needed]

Accolades[]

In 2004, D.O.A. was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[8][9]

The film was nominated for two American Film Institute lists:

- 2001: AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills[10]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10 mystery[11]

Production[]

The shot of Edmond O'Brien running down Market Street (between 4th and 6th Streets) in San Francisco was a "stolen shot," taken without city permits, with some pedestrians visibly confused as O'Brien bumps into them. D.O.A. producer Harry Popkin owned the Million Dollar Theater at the southwest corner of Broadway and Third Street in downtown Los Angeles, directly across the street from the Bradbury Building at 304 South Broadway, where O'Brien's character confronted his murderer. Director Rudolph Maté liberally used Broadway and the Bradbury Building during location shooting and included the Million Dollar Theater's blazing marquee in the background. The theater would later serve the same function when Ridley Scott filmed Blade Runner at the Bradbury Building.

After "The End" and before the listing of the cast, a credit states the medical aspects of this film are based on scientific fact, and that "luminous toxin is a descriptive term for an actual poison."

The bop jazz band playing at the Fisherman's Club while O'Brien's glass is being spiked was filmed on a Los Angeles soundstage after principal photography was completed. According to Jim Dawson in his 1995 book Nervous Man Nervous: Big Jay McNeely and the Rise of the Honking Tenor Sax, the sweating tenor saxophone player was James Streeter, also known as James Von Streeter. Other band members were Shifty Henry (bass), Al "Cake" Wichard (drums), Ray LaRue (piano), and Teddy Buckner (trumpet). However, rather than use the live performance, the music director went back and rerecorded the soundtrack with a big band, not a quintet as seen in the film, led by saxophonist Maxwell Davis.[12] Film score was composed by Dimitri Tiomkin.[13]

Remakes and influence[]

The March 16, 1951, radio episode of The Adventures of Sam Spade features a victim reporting his own murder at police headquarters.[14] D.O.A. was dramatized as an hour-long radio play on the June 21, 1951, broadcast of Screen Director's Playhouse, starring Edmond O'Brien in his original role.

The film was remade in Australia in 1969 as Color Me Dead, directed by Eddie Davis.

In 1988 it was filmed again as D.O.A., directed by Annabel Jankel and Rocky Morton, with Dennis Quaid as the protagonist.

In 2011, the Overtime Theater staged a world-premiere musical based on the classic film noir. D.O.A. a Noir Musical was written and adapted by Jon Gillespie and Matthew Byron Cassi, directed by Cassi, with original jazz and blues music composed by Jaime Ramirez and lyrics by Ramirez and Gillespie. The new musical played to sold-out audiences during its five-week run, and received two ATAC Globe Awards in 2012 for "Best Adapted Script" and "Best Original Score."[15]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Hayes, David P. (2008). "The Copyright Office Records an Invalid Renewal — Then Corrects Its Error". The Copyright Registration and Renewal Information Chart and Web Site. Retrieved 2015-06-14.

- ^ "D.O.A. (1950)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "Melodrama Opens at Criterion (Published 1950)". The New York Times. May 1, 1950.

- ^ Hirsch, Foster (1981). Film Noir: The Dark Side of the Screen. ISBN 0-306-81039-5.

- ^ Rode, A.K. (August 30, 2000). "D.O.A. (1949)". Film Monthly. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ Wood, David (February 26, 2001). "BBC review: D.O.A." BBC. Archived from the original on 2001-03-04.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (August 1, 2000). ""D.O.A.": A murdered man tracks his own killer in this ahead-of-its-time 1950 noir thriller". Salon. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- ^ "Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-09-24.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2016.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Dawson, Jim. Nervous Man Nervous: Big Jay McNeely and the Rise of the Honking Tenor Sax. Big Nickel Publishing, 1995.

- ^ D.O.A. [Soundtrack]: Amazon.co.uk: Music

- ^ Spier, William (March 16, 1951). "The Sinister Siren Caper". The Adventures of Sam Spade. NBC. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "22nd Annual ATAC Globe Awards: 2011-2012". Retrieved 2016-07-02.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to D.O.A. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: D.O.A. (1950 film) |

- D.O.A. at IMDb

- D.O.A. at Rotten Tomatoes

- D. O. A. is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- D.O.A. at the TCM Movie Database

- D.O.A. at AllMovie

- D.O.A. at the American Film Institute Catalog

- D.O.A. essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 434-435

- 1950 films

- English-language films

- 1949 films

- 1940s crime drama films

- 1940s psychological thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- American films

- American black-and-white films

- Film noir

- Films scored by Dimitri Tiomkin

- Films directed by Rudolph Maté

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set in Palm Springs, California

- Films set in San Francisco

- Films set in the San Francisco Bay Area

- United Artists films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Films adapted into radio programs

- Poisoning in film

- 1940s crime thriller films

- American crime drama films

- 1949 drama films