Bradbury Building

Bradbury Building | |

From the corner of West 3rd Street and South Broadway (2005) | |

| |

| Location | 304 South Broadway Los Angeles, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°3′1.93″N 118°14′52.30″W / 34.0505361°N 118.2478611°WCoordinates: 34°3′1.93″N 118°14′52.30″W / 34.0505361°N 118.2478611°W |

| Built | 1893[1] |

| Architect | Sumner Hunt, George Wyman |

| Architectural style | Italian Renaissance Revival, Romanesque Revival, Chicago School |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000144 |

| LAHCM No. | 6 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 14, 1971[3] |

| Designated NHL | May 5, 1977[4] |

| Designated LAHCM | September 21, 1962[2] |

The Bradbury Building is an architectural landmark in downtown Los Angeles, California. Built in 1893,[1] the five-story office building is best known for its extraordinary skylit atrium of access walkways, stairs and elevators, and their ornate ironwork. The building was commissioned by Los Angeles gold-mining millionaire Lewis L. Bradbury and constructed by draftsman George Wyman from the original design by Sumner Hunt.[5] It appears in many works of fiction and has been the site of many movie and television shoots and music videos.

The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971, and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1977, one of only four office buildings in Los Angeles to be so honored.[6] It was also designated a landmark by the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission[7] and is the city's oldest landmarked building.[8]

History[]

19th century[]

Lewis L. Bradbury (November 6, 1823 – July 15, 1892)[9][10][11] was a gold-mining millionaire[6] – he owned the Tajo mine in Sinaloa, Mexico – who became a real estate developer in the later part of his life.[12] In 1892 he began planning to construct a five-story building at Broadway and Third Street in Los Angeles, close to the Bunker Hill neighborhood. A local architect, Sumner Hunt, was hired to design the building, and turned in a completed design,[5] but Bradbury dismissed Hunt's plans as inadequate to the grand building he wanted. He then hired George Wyman, one of Hunt's draftsmen, to do the design.[13] Bradbury supposedly felt that Wyman understood his own vision of the building better than Hunt did, but there is no concrete evidence that Wyman changed Hunt's design, which has raised some controversy about who should be considered to be the architect of the building.[5] Wyman had no formal education as an architect, and was working for Hunt for $5 a week at the time.[6]

The building opened in 1893, some months after Bradbury's death in 1892,[9] and was completed in 1894, at the total cost of $500,000,[6] about three times the original budget of $175,000.[14]

20th century[]

The building has operated as an office building for most of its history. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1977.[4][15] It was purchased by noted developer and champion of downtown restoration Ira Yellin[16] in the early 1980s,[17] who invested $7 million in restoration,[6] preservation, and seismic retrofitting between 1989-1991. As part of the restoration, a storage area at the south end of the building was converted to a new rear entrance portico, connecting the building more directly to Biddy Mason Park and the adjacent Broadway Spring Center parking garage. The building's lighting system was also redesigned, bringing in alabaster wall sconces from Spain.

Since 1996, the building has served as the headquarters for the Los Angeles Police Department's Internal Affairs division[18] and other government agencies. The LAPD Board of Rights holds officer discipline hearings here, and within the force it is given the nickname "the Ovens", because officers see it as the place they "get burned."[19] The LAPD has a 50-year lease on their space.[18]

21st century[]

The building was purchased for $6 million in 2003 by a Hong Kong investor, less than the $7 million Ira Yellin invested just to rehabilitate and seismically retrofit the structure after acquiring it in 1989,[20] a reflection of Yellin's commitment to downtown preservation and restoration.[20] It was never listed for sale, only offered to a select group of potential buyers who would respect its legacy and retain its character. The building, according to Yellin’s widow, Adele, at the time, was “in very good hands”.[20]

From 2001 to 2003 the Museum of Architecture and Design had its home there.[21][22][23] In 2007, the Morono Kiang Gallery of Chinese art opened in the building.[24]

Several of the offices are rented out to private concerns, including Red Line Tours. The retail spaces on the first floor currently house Ross Cutlery, where O. J. Simpson purchased a stiletto that figured in his murder trial, a Subway sandwich restaurant, a Blue Bottle Coffee shop, and a real estate sales office for loft conversions in other nearby historic buildings.

As of 2018, the Berggruen Institute maintains its offices in the building.[25]

Architecture[]

The building's undistinguished exterior facade of brown brick, sandstone and terra cotta detailing was designed in the commercial vernacular Italian Renaissance Revival style current at the time. Its interior is its most notable part.[26]

The narrow entrance lobby, with its low ceiling and minimal light "has the look of a Parisian alley of arched windows", and opens into a bright naturally lit great "awe-inspiring cathedral-like"[14] center court. Robert Forster, star of the TV series Banyon that used the building for his office, described it as "one of the great interiors of L.A. Outside it doesn't look like much, but when you walk inside, suddenly you're back a hundred and twenty years."[27]

The five-story central court features glazed and unglazed yellow and pink bricks,[14] ornamental cast iron,[20] tiling, Italian marble, Mexican tile,[6] decorative terra cotta[14] and polished wood, capped by a skylight that allows the court to be flooded with natural rather than artificial light, creating ever-changing shadows and accents during the day. At the time the building was completed, it featured the largest plate-glass windows in Los Angeles.[6]

Open "bird-cage" elevators surrounded by wrought-iron grillwork go up to the fifth floor.[6]

Geometric patterned staircases and wrought-iron and polished oak railings are used abundantly throughout. The wrought-iron was created in France and displayed at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair before being installed in the building. Freestanding mail-chutes also feature ironwork. The overall effect, according to a Los Angeles Times writer, is "a mesmerizing degree of symmetry and visual complexity".[14]

Tourism[]

The building is a popular tourist attraction. It is open daily and staffed by a government worker who provides historical background on it. Casual visitors are only permitted up to the first landing. Brochures and tours are also available. It is close to three other downtown Los Angeles landmarks: the Grand Central Market, the Million Dollar Theater (across the street) and Angels Flight (two blocks away). Access is via the Los Angeles MTA Red Line's Civic Center exit, three blocks distant.

Gallery[]

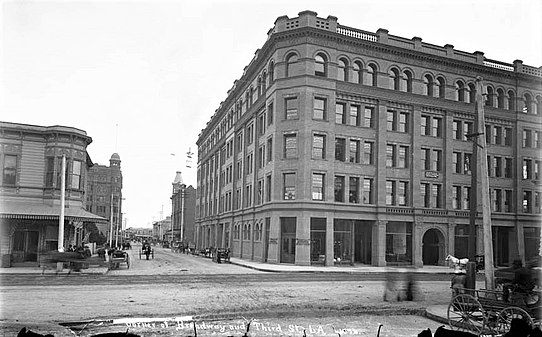

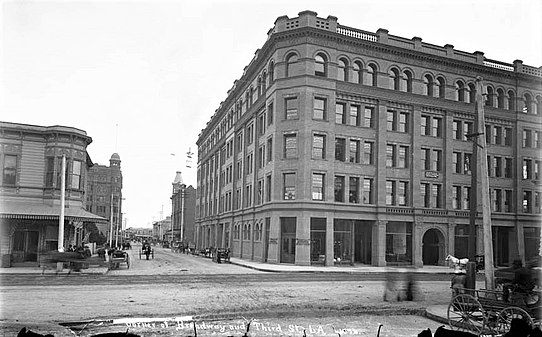

When it opened in 1894, the Bradbury Building towered above its neighbors and became the southwestern anchor of the business district, then centered around First and Main.[28]

Front entrance

Oblique view of central court from balcony

Detail of stairway ironwork

A fire in the building in 1947

The building's distinctive open elevators and large glass atrium

In popular culture[]

The Bradbury Building made a memorable place in film history as the insurance office central to the 1945 film noir classic Double Indemnity.[29] It has subsequently been featured prominently as a setting in many films, television shows, and in literature – particularly in the science fiction genre.[30] Most notably, the building is a setting in the 1982 science fiction film Blade Runner, for the character J. F. Sebastian's apartment, and the climactic rooftop scene.[31]

The Bradbury Building appeared in the noir films The Unfaithful (1947), Shockproof (1949), D.O.A. (1949), and I, The Jury (1953) [32] (the latter filmed in 3-D). M (1951), a remake of the 1931 German film, contains a long search sequence filmed in the building, and a notable shot through the roof's skylight. The five-story atrium also substituted for the interior of the seedy skid row hotel depicted in the climax of Good Neighbor Sam (1964).

The building is also featured in China Girl (1942), The White Cliffs of Dover (1944),[33] Indestructible Man (1956), Caprice (1967),[33] Marlowe (1969),[32] the 1972 made-for-television movie The Night Strangler,[30] Chinatown (1974), The Cheap Detective (1978),[33] Avenging Angel (1985),[34] Murphy's Law (1986), The Dreamer of Oz (1990 TV movie), 1994's Wolf and Disclosure, Lethal Weapon 4 (1998), Pay It Forward (2000), What Women Want (2000),[35] (500) Days of Summer (2009), and The Artist (2011).

Television series that featured the building include the 1964 The Outer Limits episode "Demon with a Glass Hand", and the 1962 Perry Mason episode "The Case of the Double-Entry Mind." During the season six episodes (1963–64) of the series 77 Sunset Strip, the Stuart "Stu" Bailey character had his office in the Bradbury. In Quantum Leap the building is seen carrying the name "Gotham Towers" in "Play It Again, Seymour", the last episode of the first season (1989). The building appeared in at least one episode of the television series Banyon (1972–73), where it was used as Robert Forster's office,[36] City of Angels (1976) and Mission: Impossible (1966–73),[34] as well as Ned and Chuck's Apartment in Pushing Daisies, which debuted in 2007.[30] The building was also the setting for a scene from the series FlashForward in the episode "Let No Man Put Asunder". In 2010 the building was transplanted to New York City for a two-part episode of CSI NY. The Bradbury Building and a fake New York City subway entrance across the street were also used to represent the exterior of New York's High School for the Performing Arts in the opening credits of the television series Fame. The building appears as itself in multiple episodes of the fourth season of Amazon Studios' original series Bosch, in both exterior establishing shots, and interior shots.

The Bradbury appeared in a 1979 music video by Cher called "Take Me Home" in addition to music videos from the 1980s by Heart, Janet Jackson, Earth Wind and Fire and Genesis, and a Pontiac Pursuit commercial. Part of Janet Jackson's 1989 film short Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1814 was filmed in the building as well. The interior appears in the music video for the Pointer Sisters' 1980 song, "He's So Shy". The Bradbury Building was prominently featured in Monica's 1998 single "The First Night" as well in Tony! Toni! Toné!'s "Let's Get Down" music video. In 2016, the interiors were featured in the music video for "The Road" by Chinese musician Huang Zitao.[37]

The Bradbury has frequently appeared in popular literature. In the "Nathan Heller" series of detective novels by Max Allan Collins, Heller's A-1 Detective Agency's Los Angeles offices are housed in the Bradbury, as shown in the novel Angel in Black. In the Star Trek novel The Case of the Colonist's Corpse: A Sam Cogley Mystery, the protagonist works from the Bradbury Building four hundred years in the future. Other appearances occur in The Man With The Golden Torc by Simon R. Green, Angels Flight and The Black Box by Michael Connelly, and the science fiction multiple novel series The World Of Tiers by Philip Jose Farmer.[30]

DC Comics and Marvel Comics – the latter of which has offices in the real Bradbury Building – both published comic book series based on characters that work in the historic landmark. The building serves as the headquarters for the Marvel Comics team The Order, and in the DC universe, the Human Target runs his private investigation agency from the building.[30]

The building was used for the music video for "Say Something", a song released on January 25, 2018 by Justin Timberlake featuring Chris Stapleton.

The Bradbury Building was featured in "On Location", episode 172 of the podcast 99% Invisible.[38]

The building interior was shown in the title sequence for the TV series The Ray Bradbury Theater, which aired from 1985 to 1992.[citation needed]

See also[]

- List of Registered Historic Places in Los Angeles

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Nomination Form. The National Register of Historic Places" (PDF).

- ^ Los Angeles Department of City Planning (2007-09-07). "Historic - Cultural Monuments (HCM) Listing: City Declared Monuments" (PDF). City of Los Angeles. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2008-05-28. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Bradbury Building". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2007-10-20. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Bradbury Building" on the Los Angeles Conservancy website

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "New Shine for an Old Gem: Renovated Bradbury Building is a credit to Los Angeles architecture". Los Angeles Times. October 5, 1991.

- ^ Muchnich, Suzanne. "Old Friends Meet Again : Bradbury Building, 98, Sits for Photographer, 80" Los Angeles Times (August 3, 1991)

- ^ "Bradbury Building Renovation" Los Angeles Times (November 12, 1989)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wakim, Marielle. "It Happened This Week in L.A. History: The City Mourns Lewis L. Bradbury" Los Angeles (July 16, 1892)

- ^ "Louis L. Bradbury" on the Family History Machine" website

- ^ "Bradbury Family Papers: A Mexican-American Family's Story, 1876-1965" Archived 2014-01-12 at the Wayback Machine on the University of California, Davis University Library website

- ^ "Special Collections Exhibits". www.library.ucdavis.edu.

- ^ Tarr, Jeremy (2019-03-23). "10 Incredible, Insane, and Mostly True Stories About Downtown Los Angeles". Fodors Travel Guide. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Ferrell, David. "The Bradbury Sparkles as Jewel in City Landscape" Los Angeles Times (October 10, 2002)

- ^ Pitts, Carolyn (February 22, 1977). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Bradbury Building". National Park Service. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) and Accompanying 12 photos, exterior and interior, from 1971, 1965, and undated. (4.42 MB) - ^ "Ira Yellin, 62; Civic Leader and Longtime Champion of the City's Historic Core". Los Angeles Times. September 11, 2002.

- ^ Latker, Loren. "Elevators at the Bradbury" on the Shamus Town website

- ^ Jump up to: a b "LAPD Unit to Move to Historic Building" Los Angeles Times (February 13, 1996)

- ^ Christopher Goffard; Joel Rubin & Kurt Streeter (2013-12-08). "The Manhunt for Christopher Dorner". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Vincent, Roger (July 30, 2003). "Hong Kong Investor With Eye on the Past Acquires Landmark Bradbury Building". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- ^ "About A+D" Archived January 10, 2014, at the Wayback Machine on the Architecture and Design Museum: Los Angeles website

- ^ Stevens, James. "Back to the Bradbury" Los Angeles Times (February 9, 2001)

- ^ Roug, Louise. "Another location for A + D" Los Angeles Times (December 21, 2003)

- ^ Muchnic, Suzanne. "An artful addition to Bradbury's interior" Los Angeles Times (June 24, 2007)

- ^ "This Star Trek Federation-Style Org Examines Human Transformation". PCMAG. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- ^ "The Bradbury Building" Archived 2014-01-12 at the Wayback Machine on the American Institute of Architects, Los Angeles Chapter website

- ^ Etter, Jonathan (2008). Quinn Martin, Producer: A Behind-the-scenes History of Qm Productions and Its Founder. McFarland & Company. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7864-3867-9.

- ^ "The Opening of North Broadway". Los Angeles Times. October 9, 1895. p. 6.

- ^ "Setting the scene in L.A." Los Angeles Times. November 4, 2003.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "The Most Famous Building In Science Fiction". io9. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ^ Bukatman, Scott (1997). Blade Runner. British Film Institute. ISBN 978-0-85170-623-8. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bible, Karie; Wanamaker, Marc; Medved, Harry (2010). Location Filming in Los Angeles. Arcadia Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7385-8132-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Smith, Leon (1988). Hollywood Goes on Location. Los Angeles: Pomegranate Press. p. 184. ISBN 0-938817-07-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Blade Runner Film Locations: Bradbury Building". BRmovie.com. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ^ "What Women Want". Retrieved 2021-05-23.

- ^ MobileReference. Travel Los Angeles: City Guide and Map 2007. ISBN 9781605010366

- ^ "ZTAO - The Road" – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "On Location - 99% Invisible". 99% Invisible. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bradbury Building, Los Angeles. |

- Public Art in L.A. – Bradbury Building, A History

- Los Angeles Conservancy

- BRmovie.com Blade Runner Film Locations

- University of Southern California's L.A. Walking Tour

- Inside the Bradbury Building webinar

- Office buildings in Los Angeles

- Buildings and structures in Downtown Los Angeles

- Commercial buildings completed in 1893

- Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments

- Commercial buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Los Angeles

- National Historic Landmarks in California

- Office buildings completed in 1893

- 1893 establishments in California

- 19th century in Los Angeles

- Historic American Buildings Survey in California

- Sumner Hunt buildings

- Italian Renaissance Revival architecture in the United States

- Renaissance Revival architecture in California

- Romanesque Revival architecture in California

- Chicago school architecture in California

- Broadway (Los Angeles)

- 3rd Street (Los Angeles)