DC Comics

DC Comics' current logo, introduced with the DC Rebirth relaunch in 2016 | |

| Parent company | DC Entertainment (Warner Bros.) (WarnerMedia Studios & Networks) (WarnerMedia) (AT&T) (spin-out into independent entity pending, to be merged with Discovery, Inc.) |

|---|---|

| Status | Active |

| Founded | 1934[1] (as National Allied Publications) |

| Founder | Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Headquarters location | 2900 West Alameda Avenue, Burbank, California |

| Distribution |

|

| Key people |

|

| Publication types | List of publications |

| Fiction genres |

|

| Imprints | List of imprints |

| No. of employees | ~230[3] |

| Official website | www |

DC Comics, Inc. is an American comic book publisher and the flagship unit of DC Entertainment,[4][5] a subsidiary of the Warner Bros. Global Brands and Experiences division of Warner Bros., which itself is a subsidiary of AT&T's WarnerMedia through its Studios & Networks division.

DC Comics is one of the largest and oldest American comic book companies. The majority of its publications take place within the fictional DC Universe and feature numerous culturally iconic heroic characters, such as Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman. It is widely known for some of the most famous and recognizable teams including the Justice League, the Justice Society of America, and the Teen Titans. The universe also features a large number of well-known supervillains who oppose the superheroes such as Lex Luthor, the Joker, and Deathstroke. The company has published non-DC Universe-related material, including Watchmen, V for Vendetta, Fables and many titles under their alternative imprint Vertigo.

Originally in Manhattan at 432 Fourth Avenue, the DC Comics offices have been located at 480 and later 575 Lexington Avenue; 909 Third Avenue; 75 Rockefeller Plaza; 666 Fifth Avenue; and 1325 Avenue of the Americas. DC had its headquarters at 1700 Broadway, Midtown Manhattan, New York City, but DC Entertainment relocated its headquarters to Burbank, California in April 2015.[6]

Penguin Random House Publisher Services distributes DC Comics' books to the bookstore market,[7] while Diamond Comic Distributors supplied the comics shop direct market[6][8] until June 2020, where Lunar Distribution and UCS Comic Distributors, who already distributed to the direct market due to Diamond's distribution interruption as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, replaced Diamond to distribute to that market.[2] DC Comics and its longtime major competitor Marvel Comics (acquired in 2009 by The Walt Disney Company, WarnerMedia's main competitor) together shared approximately 70% of the American comic book market in 2017,[9] though this number may give a distorted view since graphic novels are excluded. With the sales of all books included, DC is the second biggest publisher, after Viz Media, and Marvel is third.[10]

History[]

Golden Age[]

| Pioneers of DC Comics who started in the 1930s.[11] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson | Jerry Siegel | Joe Shuster | Bob Kane | Bill Finger | Sheldon Mayer | Gardner Fox |

| Founder of DC Comics | Creator of Superman | Creator of Superman | Creator of Batman and The Joker | Creator of Batman and The Joker | Early founder | Created various characters |

Entrepreneur Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson founded National Allied Publications in Autumn 1934 intended as an American comic book publishing company.[1][13][14] The first publishing of the company debuted with the tabloid-sized New Fun: The Big Comic Magazine #1 (the first of a comic series later called More Fun Comics) with a cover date of February 1935. An anthology title essential for containing original stories not reprinted from newspaper strips unlike many comic book series before.[12][15] While superhero comics are what DC Comics is known for throughout modern times, the genres in the anthology titles consisted of funnies, Western comics and adventure-related stories starting out. The character Doctor Occult, created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in December 1935 within the issue No. 6 of New Fun Comics, is considered as the earliest recurring superhero created by DC that is still used.[16][17] The company created a second recurring title called New Comics No. 1 released in December 1935 which would be the start of the long-running Adventure Comics series featuring many anthology titles as well.[18]

Wheeler-Nicholson's next and final title, Detective Comics, advertised with a cover illustration dated December 1936, eventually premiered three months late with a March 1937 cover date. The themed anthology that revolved originally on fictional detective stories became in modern times the longest-running ongoing comic series. A notable debut in the first issue was Slam Bradley created in contribution by Malcom-Wheeler-Nicholson, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster.[17] In 1937, in debt to printing-plant owner and magazine distributor Harry Donenfeld — who also published pulp magazines and operated as a principal in the magazine distributorship Independent News — Wheeler-Nicholson had to take Donenfeld on as a partner to publish Detective Comics No. 1. Detective Comics, Inc. (which would help inspire the abbreviation DC) was formed, with Wheeler-Nicholson and Jack S. Liebowitz, Donenfeld's accountant, listed as owners. Major Wheeler-Nicholson remained for a year, but cash-flow problems continued, and he was forced out. Shortly afterwards, Detective Comics, Inc. purchased the remains of National Allied, also known as Nicholson Publishing, at a bankruptcy auction.[19]

Meanwhile, Max Gaines, formed the sister company All-American Publications around 1938.[20] Detective Comics, Inc. soon launched a new anthology title, entitled Action Comics. Issue#1, cover dated in June 1938, first featured characters such as Superman by Siegel and Shuster, Zatara by Fred Guardineer and Tex Thompson by Ken Finch and Bernard Baily. It is considered to be the first comic book to feature the new character archetype—soon known as "superheroes" and was a sales hit bringing to life a new age of comic books with the credit going to the first appearance of Superman both being featured on the cover and within the issue. It is now one of the most expensive and valuable comic book issues of all time.[21] The issue's first featured tale which starred Superman was the first to feature an origin story of superheroes with the reveal of an unnamed planet later known as Krypton that he is said to be from. The issue also contained the first essential supporting character and one of the earliest essential female characters in comics with Lois Lane as Superman's first depicted romantic interest.[22] The Green Hornet-inspired character known as the Crimson Avenger by Jim Chamber was featured in Detective Comics No. 20 (October 1938). The character makes a distinction of being the first masked vigilante published by DC.[23][24] An unnamed "office boy" retconned as Jimmy Olsen's first appearance was revealed in Action Comics #6's (November 1938) Superman story by Siegel and Shuster.[25][26]

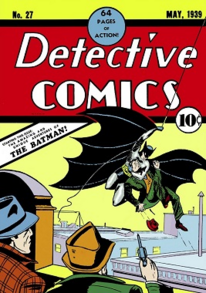

Starting in 1939, Siegel and Shuster's Superman would be the first comic derived character to appear outside of comic magazines and later appear in newspaper strips starring himself which first introduced Superman's biological parents, Jor-El and Lara.[27] All-American Publications' first comic series called All-American Comics was first published in April 1939.[22] The series of Detective Comics would make successful history as first featuring Batman by Bob Kane and Bill Finger in issue#27 (March 1939) with the request of more superhero titles. Batman was depicted as a masked vigilante depicted as wearing a suit known as the Batsuit along with riding a car that would later be referred to as the Batmobile. Also within the Batman story was the supporting character, James Gordon, Police commissioner of what later would be Gotham City Police Department.[28] Despite being a parody, All-American Publications introduced the earliest female character who would later be a female superhero called Red Tornado (though disguised as a male) in Ma Hunkel who first appeared in the "Scribbly" stories in All-American Comics No. 3 (June 1939).[29] Another important Batman debut was the introduction of the fictional mansion known as Wayne Manor first seen in Detective Comics No. 28 (June 1939).[28] The series Adventure Comics would eventually follow in the Action Comics and Detective Comics series footsteps with featuring a new recurring superhero. The superhero called Sandman was first written in issue No. 40 (cover date: July 1939).[30] Action Comics No. 13 (June 1939) introduced the first recurring Superman enemy referred to as the Ultra-Humanite first introduced by Siegel and Shuster, commonly cited as one of the earliest supervillains in comic books.[31] The character Superman had another breakthrough with progress when the character had his own comic book starring him which was unheard of at the time.[32] The first issue introduced in June 1939 helped directly introduce Superman's adoptive parents, Jonathan and Martha Kent by Siegel and Shuster.[25] Detective Comics #29 (July 1939) introduced the Batman's utility belt by Gardner Fox.[33][28] Outside of DC's publishing, a character later integrated as DC was introduced by Fox Feature Syndicate named the Blue Beetle released in August 1939.[34][35] Fictional cities would be a common theme of DC. The first revealed city was Superman's home city, Metropolis, that was originally named in Action Comics No. 16 in September 1939.[36][37] Detective Comics No. 31 in September 1939 by Gardner Fox, Bob Kane and Sheldon Moldoff introduced a romantic interest of Batman called Julie Madison, the weapon known as the Batarang that Batman commonly uses along with the fictional aircraft called the Batplane.[28] Batman's origin would first be used in Detective Comics No. 33 (Nov. 1939) first depicting the death of Thomas Wayne and Martha Wayne by a mugger. The origin story would remain crucial for the fictional character since the inception.[12][38] The Daily Planet (a common setting of Superman) was first named in a newspaper strip of Superman around November 1939.[39] The superhero Doll Man was the first superhero by Quality that DC now owns.[40] Fawcett Comics was formed around 1939 and would end up as DC's original competitor company in the next decade.[41]

National Allied Publications soon merged with Detective Comics, Inc., forming National Comics Publications on September 30, 1946.[a] National Comics Publications absorbed an affiliated concern, Max Gaines' and Liebowitz' All-American Publications. In the same year Gaines let Liebowitz buy him out, and kept only Picture Stories from the Bible as the foundation of his own new company, EC Comics. At that point, "Liebowitz promptly orchestrated the merger of All-American and Detective Comics into National Comics... Next he took charge of organizing National Comics, [the self-distributorship] Independent News, and their affiliated firms into a single corporate entity, National Periodical Publications".[43] National Periodical Publications became publicly traded on the stock market in 1961.[44][45]

Despite the official names "National Comics" and "National Periodical Publications", the company began branding itself as "Superman-DC" as early as 1940, and the company became known colloquially as DC Comics for years before the official adoption of that name in 1977.[46]

The company began to move aggressively against what it saw as copyright-violating imitations from other companies, such as Fox Comics' Wonder Man, which (according to court testimony) Fox started as a copy of Superman. This extended to DC suing Fawcett Comics over Captain Marvel, at the time comics' top-selling character (see National Comics Publications, Inc. v. Fawcett Publications, Inc.). Faced with declining sales and the prospect of bankruptcy if it lost, Fawcett capitulated in 1953 and ceased publishing comics. Years later, Fawcett sold the rights for Captain Marvel to DC—which in 1972 revived Captain Marvel in the new title Shazam! featuring artwork by his creator, C. C. Beck. In the meantime, the abandoned trademark had been seized by Marvel Comics in 1967, with the creation of their Captain Marvel, forbidding the DC comic itself to be called that. While Captain Marvel did not recapture his old popularity, he later appeared in a Saturday morning live action TV adaptation and gained a prominent place in the mainstream continuity DC calls the DC Universe.

When the popularity of superheroes faded in the late 1940s, the company focused on such genres as science fiction, Westerns, humor, and romance. DC also published crime and horror titles, but relatively tame ones, and thus avoided the mid-1950s backlash against such comics. A handful of the most popular superhero-titles, including Action Comics and Detective Comics, the medium's two longest-running titles, continued publication.

Silver Age[]

In the mid-1950s, editorial director Irwin Donenfeld and publisher Liebowitz directed editor Julius Schwartz (whose roots lay in the science-fiction book market) to produce a one-shot Flash story in the try-out title Showcase. Instead of reviving the old character, Schwartz had writers Robert Kanigher and John Broome, penciler Carmine Infantino, and inker Joe Kubert create an entirely new super-speedster, updating and modernizing the Flash's civilian identity, costume, and origin with a science-fiction bent. The Flash's reimagining in Showcase No. 4 (October 1956) proved sufficiently popular that it soon led to a similar revamping of the Green Lantern character, the introduction of the modern all-star team Justice League of America (JLA), and many more superheroes, heralding what historians and fans call the Silver Age of Comic Books.

National did not reimagine its continuing characters (primarily Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman), but radically overhauled them. The Superman family of titles, under editor Mort Weisinger, introduced such enduring characters as Supergirl, Bizarro, and Brainiac. The Batman titles, under editor Jack Schiff, introduced the successful Batwoman, Bat-Girl, Ace the Bat-Hound, and Bat-Mite in an attempt to modernize the strip with non-science-fiction elements. Schwartz, together with artist Infantino, then revitalized Batman in what the company promoted as the "New Look", with relatively down-to-Earth stories re-emphasizing Batman as a detective. Meanwhile, editor Kanigher successfully introduced a whole family of Wonder Woman characters having fantastic adventures in a mythological context.

Since the 1940s, when Superman, Batman, and many of the company's other heroes began appearing in stories together, DC's characters inhabited a shared continuity that, decades later, was dubbed the "DC Universe" by fans. With the story "Flash of Two Worlds", in Flash No. 123 (September 1961), editor Schwartz (with writer Gardner Fox and artists Infantino and Joe Giella) introduced a concept that allowed slotting the 1930s and 1940s Golden Age heroes into this continuity via the explanation that they lived on an other-dimensional "Earth 2", as opposed to the modern heroes' "Earth 1"—in the process creating the foundation for what was later called the DC Multiverse.

DC's introduction of the reimagined superheroes did not go unnoticed by other comics companies. In 1961, with DC's JLA as the specific spur,[b] Marvel Comics writer-editor Stan Lee and a robust creator Jack Kirby ushered in the sub-Silver Age "Marvel Age" of comics with the debut issue of The Fantastic Four.[48] Reportedly, DC ignored the initial success of Marvel with this editorial change until its consistently strengthening sales, albeit also benefiting Independent News' business as their distributor as well, made that impossible. That commercial situation especially applied with Marvel's superior sell-through percentage numbers which were typically 70% to DC's roughly 50%, which meant DC's publications were barely making a profit in comparison after returns from the distributors were calculated while Marvel was making an excellent profit by comparison.[49]

However, the senior DC staff were reportedly at a loss at this time to understand how this small publishing house was achieving this increasingly threatening commercial strength. For instance, when Marvel's product was examined in a meeting, Marvel's emphasis on more sophisticated character-based narrative and artist-driven visual storytelling was apparently ignored for self-deluding guesses at the brand's popularity which included superficial reasons like the presence of the color red or word balloons on the cover, or that the perceived crudeness of the interior art was somehow more appealing to readers. When Lee learned about DC's subsequent experimental attempts to imitate these perceived details, he amused himself by arranging direct defiance of those assumptions in Marvel's publications as sales strengthened further to frustrate the competition.[50]

However, this ignorance of Marvel's true appeal did not extend to some of the writing talent during this period, from which there were some attempts to emulate Marvel's narrative approach. For instance, there was the Doom Patrol series by Arnold Drake, a writer who previously warned the management of the new rival's strength;[51] a superhero team of outsiders who resented their freakish powers,[52] which Drake later speculated was plagiarized by Stan Lee to create The X-Men.[53] There was also the young Jim Shooter who purposely emulated Marvel's writing when he wrote for DC after much study of both companies' styles, such as for the Legion of Super-Heroes feature.[54]

A 1966 Batman TV show on the ABC network sparked a temporary spike in comic book sales, and a brief fad for superheroes in Saturday morning animation (Filmation created most of DC's initial cartoons) and other media. DC significantly lightened the tone of many DC comics—particularly Batman and Detective Comics—to better complement the "camp" tone of the TV series. This tone coincided with the famous "Go-Go Checks" checkerboard cover-dress which featured a black-and-white checkerboard strip (all DC books cover dated February 1966 until August 1967) at the top of each comic, a misguided attempt by then-managing editor Irwin Donenfeld to make DC's output "stand out on the newsracks".[55] In particular, DC artist, Carmine Infantino, complained that the visual cover distinctiveness made DC's titles easier for readers to see and then avoid in favor of Marvel's titles.[56]

In 1967, Batman artist Infantino (who had designed popular Silver Age characters Batgirl and the Phantom Stranger) rose from art director to become DC's editorial director. With the growing popularity of upstart rival Marvel Comics threatening to topple DC from its longtime number-one position in the comics industry, he attempted to infuse the company with more focus towards marketing new and existing titles and characters with more adult sensibilities towards an emerging older age group of superhero comic book fans that grew out of Marvel's efforts to market their superhero line to college-aged adults. He also recruited major talents such as ex-Marvel artist and Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko and promising newcomers Neal Adams and Denny O'Neil and replaced some existing DC editors with artist-editors, including Joe Kubert and Dick Giordano, to give DC's output a more artistic critical eye.

Kinney National Company/Warner Communications subsidiary (1967–1990)[]

In 1967, National Periodical Publications was purchased by Kinney National Company,[57] which purchased Warner Bros.-Seven Arts in 1969. Kinney National spun off its non-entertainment assets in 1972 (as National Kinney Corporation) and changed its name to Warner Communications Inc.

In 1970, Jack Kirby moved from Marvel Comics to DC, at the end of the Silver Age of Comics, in which Kirby's contributions to Marvel played a large, integral role. Given carte blanche to write and illustrate his own stories, he created a handful of thematically linked series he called collectively The Fourth World. In the existing series Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen and in his own, newly launched series New Gods, Mister Miracle, and The Forever People, Kirby introduced such enduring characters and concepts as archvillain Darkseid and the other-dimensional realm Apokolips. Furthermore, Kirby intended their stories to be reprinted in collected editions, in a publishing format that was later called the trade paperback, which became a standard industry practice decades later. While sales were respectable, they did not meet DC management's initially high expectations, and also suffered from a lack of comprehension and internal support from Infantino. By 1973 the "Fourth World" was all cancelled, although Kirby's conceptions soon became integral to the broadening of the DC Universe, especially after the major toy company, Kenner Products, judged them ideal for their action figure adaptation of the DC Universe, the Super Powers Collection.[58] Obligated by his contract, Kirby created other unrelated series for DC, including Kamandi, The Demon, and OMAC, before ultimately returning to Marvel Comics.

In 1977, the company officially changed its name to DC Comics.[59] It had used the brand "Superman-DC" since the 1950s, and was colloquially known as DC Comics for years.[60]

Bronze Age[]

Following the science-fiction innovations of the Silver Age, the comics of the 1970s and 1980s became known as the Bronze Age, as fantasy gave way to more naturalistic and sometimes darker themes. Illegal drug use, banned by the Comics Code Authority, explicitly appeared in comics for the first time in Marvel Comics' story "Green Goblin Reborn!" in The Amazing Spider-Man No. 96 (May 1971), and after the Code's updating in response, DC offered a drug-fueled storyline in writer Dennis O'Neil and artist Neal Adams' Green Lantern, beginning with the story "Snowbirds Don't Fly" in the retitled Green Lantern / Green Arrow No. 85 (September 1971), which depicted Speedy, the teen sidekick of superhero archer Green Arrow, as having become a heroin addict.

Jenette Kahn, a former children's magazine publisher, replaced Infantino as editorial director in January 1976. As it happened, her first task even before being formally hired, was to convince Bill Sarnoff, the head of Warner Publishing, to keep DC as a publishing concern, as opposed to simply managing their licensing of their properties.[61] With that established, DC had attempted to compete with the now-surging Marvel by dramatically increasing its output and attempting to win the market by flooding it. This included launching series featuring such new characters as Firestorm and Shade, the Changing Man, as well as an increasing array of non-superhero titles, in an attempt to recapture the pre-Wertham days of post-War comicdom. In June 1978, five months before the release of the first Superman movie, Kahn expanded the line further, increasing the number of titles and story pages, and raising the price from 35 cents to 50 cents. Most series received eight-page back-up features while some had full-length twenty-five-page stories. This was a move the company called the "DC Explosion".[62] The move was not successful, however, and corporate parent Warner dramatically cut back on these largely unsuccessful titles, firing many staffers in what industry watchers dubbed "the DC Implosion".[63] In September 1978, the line was dramatically reduced and standard-size books returned to 17-story pages but for a still increased 40 cents.[64] By 1980, the books returned to 50 cents with a 25-page story count but the story pages replaced house ads in the books.

Seeking new ways to boost market share, the new team of publisher Kahn, vice president Paul Levitz, and managing editor Giordano addressed the issue of talent instability. To that end—and following the example of Atlas/Seaboard Comics[65] and such independent companies as Eclipse Comics—DC began to offer royalties in place of the industry-standard work-for-hire agreement in which creators worked for a flat fee and signed away all rights, giving talent a financial incentive tied to the success of their work. As it happened, the implementation of these incentives proved opportune considering Marvel Comics' Editor-in-Chief, Jim Shooter, was alienating much of his company's creative staff with his authoritarian manner and major talents there went to DC like Roy Thomas, Gene Colan, Marv Wolfman, and George Perez.[66]

In addition, emulating the era's new television form, the miniseries while addressing the matter of an excessive number of ongoing titles fizzling out within a few issues of their start, DC created the industry concept of the comic book limited series. This publishing format allowed for the deliberate creation of finite storylines within a more flexible publishing format that could showcase creations without forcing the talent into unsustainable open-ended commitments. The first such title was World of Krypton in 1979, and its positive results lead to subsequent similar titles and later more ambitious productions like Camelot 3000 for the direct market in 1982.[67]

These changes in policy shaped the future of the medium as a whole, and in the short term allowed DC to entice creators away from rival Marvel, and encourage stability on individual titles. In November 1980 DC launched the ongoing series The New Teen Titans, by writer Marv Wolfman and artist George Pérez, two popular talents with a history of success. Their superhero-team comic, superficially similar to Marvel's ensemble series X-Men, but rooted in DC history, earned significant sales[68] in part due to the stability of the creative team, who both continued with the title for six full years. In addition, Wolfman and Pérez took advantage of the limited-series option to create a spin-off title, Tales of the New Teen Titans, to present origin stories of their original characters without having to break the narrative flow of the main series or oblige them to double their work load with another ongoing title.

Modern Age[]

This successful revitalization of the Silver Age Teen Titans led DC's editors[69] to seek the same for the wider DC Universe. The result, the Wolfman/Pérez 12-issue limited series Crisis on Infinite Earths, gave the company an opportunity to realign and jettison some of the characters' complicated backstory and continuity discrepancies. A companion publication, two volumes entitled The History of the DC Universe, set out the revised history of the major DC characters. Crisis featured many key deaths that shaped the DC Universe for the following decades, and it separated the timeline of DC publications into pre- and post-"Crisis".

Meanwhile, a parallel update had started in the non-superhero and horror titles. Since early 1984, the work of British writer Alan Moore had revitalized the horror series The Saga of the Swamp Thing, and soon numerous British writers, including Neil Gaiman and Grant Morrison, began freelancing for the company. The resulting influx of sophisticated horror-fantasy material led to DC in 1993 establishing the Vertigo mature-readers imprint, which did not subscribe to the Comics Code Authority.[70]

Two DC limited series, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller and Watchmen by Moore and artist Dave Gibbons, drew attention in the mainstream press for their dark psychological complexity and promotion of the antihero.[71] These titles helped pave the way for comics to be more widely accepted in literary-criticism circles and to make inroads into the book industry, with collected editions of these series as commercially successful trade paperbacks.[72]

The mid-1980s also saw the end of many long-running DC war comics, including series that had been in print since the 1960s. These titles, all with over 100 issues, included Sgt. Rock, G.I. Combat, The Unknown Soldier, and Weird War Tales.

Time Warner/AOL Time Warner/WarnerMedia unit (1990–present)[]

In March 1989, Warner Communications merged with Time Inc., making DC Comics a subsidiary of Time Warner. In June, the first Tim Burton-directed Batman movie was released, and DC began publishing its hardcover series of DC Archive Editions, collections of many of their early, key comics series, featuring rare and expensive stories unseen by many modern fans. Restoration for many of the Archive Editions was handled by Rick Keene with colour restoration by DC's long-time resident colourist, Bob LeRose. These collections attempted to retroactively credit many of the writers and artists who had worked without much recognition for DC during the early period of comics when individual credits were few and far between.

The comics industry experienced a brief boom in the early 1990s, thanks to a combination of speculative purchasing (mass purchase of the books as collectible items, with intent to resell at a higher value as the rising value of older issues, was thought to imply that all comics would rise dramatically in price) and several storylines which gained attention from the mainstream media. DC's extended storylines in which Superman was killed, Batman was crippled and superhero Green Lantern turned into the supervillain Parallax resulted in dramatically increased sales, but the increases were as temporary as the hero's replacements. Sales dropped off as the industry went into a major slump, while manufactured "collectables" numbering in the millions replaced quality with quantity until fans and speculators alike deserted the medium in droves.

DC's Piranha Press and other imprints (including the mature readers line Vertigo, and Helix, a short-lived science fiction imprint) were introduced to facilitate compartmentalized diversification and allow for specialized marketing of individual product lines. They increased the use of non-traditional contractual arrangements, including the dramatic rise of creator-owned projects, leading to a significant increase in critically lauded work (much of it for Vertigo) and the licensing of material from other companies. DC also increased publication of book-store friendly formats, including trade paperback collections of individual serial comics, as well as original graphic novels.

One of the other imprints was Impact Comics from 1991 to 1992 in which the Archie Comics superheroes were licensed and revamped.[73][74] The stories in the line were part of its own shared universe.[75]

DC entered into a publishing agreement with Milestone Media that gave DC a line of comics featuring a culturally and racially diverse range of superhero characters. Although the Milestone line ceased publication after a few years, it yielded the popular animated series Static Shock. DC established Paradox Press to publish material such as the large-format Big Book of... series of multi-artist interpretations on individual themes, and such crime fiction as the graphic novel Road to Perdition. In 1998, DC purchased WildStorm Comics, Jim Lee's imprint under the Image Comics banner, continuing it for many years as a wholly separate imprint – and fictional universe – with its own style and audience. As part of this purchase, DC also began to publish titles under the fledgling WildStorm sub-imprint America's Best Comics (ABC), a series of titles created by Alan Moore, including The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Tom Strong, and Promethea. Moore strongly contested this situation, and DC eventually stopped publishing ABC.

2000s[]

In March 2003 DC acquired publishing and merchandising rights to the long-running fantasy series Elfquest, previously self-published by creators Wendy and Richard Pini under their WaRP Graphics publication banner. This series then followed another non-DC title, Tower Comics' series T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents, in collection into DC Archive Editions. In 2004 DC temporarily acquired the North American publishing rights to graphic novels from European publishers 2000 AD and Humanoids. It also rebranded its younger-audience titles with the mascot Johnny DC and established the CMX imprint to reprint translated manga. In 2006, CMX took over from Dark Horse Comics publication of the webcomic Megatokyo in print form. DC also took advantage of the demise of Kitchen Sink Press and acquired the rights to much of the work of Will Eisner, such as his The Spirit series and his graphic novels.

In 2004, DC began laying the groundwork for a full continuity-reshuffling sequel to Crisis on Infinite Earths, promising substantial changes to the DC Universe (and side-stepping the 1994 Zero Hour event which similarly tried to ret-con the history of the DCU). In 2005, the critically lauded Batman Begins film was released; also, the company published several limited series establishing increasingly escalated conflicts among DC's heroes, with events climaxing in the Infinite Crisis limited series. Immediately after this event, DC's ongoing series jumped forward a full year in their in-story continuity, as DC launched a weekly series, 52, to gradually fill in the missing time. Concurrently, DC lost the copyright to "Superboy" (while retaining the trademark) when the heirs of Jerry Siegel used a provision of the 1976 revision to the copyright law to regain ownership.

In 2005, DC launched its "All-Star" line (evoking the title of the 1940s publication), designed to feature some of the company's best-known characters in stories that eschewed the long and convoluted continuity of the DC Universe. The line began with All-Star Batman & Robin the Boy Wonder and All-Star Superman, with All-Star Wonder Woman and All-Star Batgirl announced in 2006 but neither being released nor scheduled as of the end of 2009.[76]

DC licensed characters from the Archie Comics imprint Red Circle Comics by 2007.[77] They appeared in the Red Circle line, based in the DC Universe, with a series of one-shots followed by a miniseries that lead into two ongoing titles, each lasting 10 issues.[75][78]

2010s[]

In 2011, DC rebooted all of its running titles following the Flashpoint storyline. The reboot called The New 52 gave new origin stories and costume designs to many of DC's characters.

DC licensed pulp characters including Doc Savage and the Spirit which it then used, along with some DC heroes, as part of the First Wave comics line launched in 2010 and lasting through fall 2011.[79][80][81]

In May 2011, DC announced it would begin releasing digital versions of their comics on the same day as paper versions.[82]

On June 1, 2011, DC announced that it would end all ongoing series set in the DC Universe in August and relaunch its comic line with 52 issue #1s, starting with Justice League on August 31 (written by Geoff Johns and drawn by Jim Lee), with the rest to follow later on in September.[83][84]

On June 4, 2013, DC unveiled two new digital comic innovations to enhance interactivity: DC2 and DC2 Multiverse. DC2 layers dynamic artwork onto digital comic panels, adding a new level of dimension to digital storytelling, while DC2 Multiverse allows readers to determine a specific story outcome by selecting individual characters, storylines and plot developments while reading the comic, meaning one digital comic has multiple outcomes. DC2 will first appear in the upcoming digital-first title, Batman '66, based on the 1960s television series and DC2 Multiverse will first appear in Batman: Arkham Origins, a digital-first title based on the video game of the same name.[85]

In 2014, DC announced an eight-issue miniseries titled Convergence which began in April 2015.[86][87][88][89]

In 2016, DC announced a line-wide relaunch titled DC Rebirth.[90] The new line would launch with an 80-page one-shot titled DC Universe: Rebirth, written by Geoff Johns, with art from Gary Frank, Ethan Van Sciver, and more. After that, many new series would launch with a twice-monthly release schedule and new creative teams for nearly every title. The relaunch was meant to bring back the legacy and heart many felt had been missing from DC characters since the launch of the New 52. Rebirth brought huge success, both financially and critically.[91][92][93]

In January 2019 it was reported that 7 of the DC's 240 person workforce were laid off, including several vice presidents.[3]

2020s[]

On February 21, 2020, the Co-Publisher of DC Comics, Dan DiDio stepped down after 10 years at that position. The company did not give a reason for the move, nor did it indicate whether it was his decision or the company's. The leadership change was the latest event in the company restructuring which began the previous month, as several top executives were laid off from the company.[94][95] However, Bleeding Cool reported that he was fired.[96]

On June 2020, Warner Bros. announced a separate DC-themed online-only convention. Known as DC FanDome, the free "immersive virtual fan experience" was a 24-hour-long event held on August 22, 2020.[97] The main presentation, entitled "DC FanDome: Hall of Heroes", was held as scheduled on August 22.[98] The remaining programming was provided through a one-day video on demand experience, "DC FanDome: Explore the Multiverse", on September 12.

As Warner Bros. and DC's response to San Diego Comic-Con's cancellation due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the convention featured information about DC-based content including the DC Extended Universe film franchise, the Arrowverse television franchise, comic books, and video games. The convention also returned for the virtual premiere of Wonder Woman 1984[99] and will once again return on October 16, 2021.[100]

In August 2020, roughly one-third of DC's editorial ranks were laid off, including the editor-in-chief, senior story editor, executive editor, and several senior VPs.[101]

In March 2021, DC relaunched their entire line once again under the banner of Infinite Frontier. After the events of the Dark Nights: Death Metal storyline, the DC Multiverse was expanded into a larger "Omniverse" where everything is canon, effectively reversing the changes The New 52 introduced a decade prior.[102]

DC Entertainment[]

| |

| Type | Subsidiary |

|---|---|

| Industry | Entertainment |

| Genre | Superhero fiction |

| Founded | 2009 |

| Headquarters | Burbank, California , United States |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products |

|

| Services | Licensing |

| Owner | WarnerMedia (a subsidiary of AT&T) |

| Parent | Warner Bros. Global Brands and Experiences (Warner Bros.) |

| Divisions |

|

| Website | www |

DC Entertainment, Inc. is a subsidiary of Warner Bros. that manages its comic book units and intellectual property (characters) in other units as they work with other Warner Bros. units.

In September 2009, Warner Bros. announced that DC Comics would become a subsidiary of DC Entertainment, Inc., with Diane Nelson, President of Warner Premiere, becoming president of the newly formed holding company and DC Comics President and Publisher Paul Levitz moving to the position of Contributing Editor and Overall Consultant there.[103] Warner Bros. and DC Comics have been owned by the same company since 1969.

On February 18, 2010, DC Entertainment named Jim Lee and Dan DiDio as Co-Publishers of DC Comics, Geoff Johns as Chief Creative Officer, John Rood as EVP (Executive Vice President) of Sales, Marketing and Business Development, and Patrick Caldon as EVP of Finance and Administration.[104]

In October 2013, DC Entertainment announced that the DC Comics offices were going to move from New York City to Warner Bros. Burbank, California, headquarters in 2015. The other units, animation, movie, TV and portfolio planning, had preceded DC Comics by moving there in 2010.[105]

DC Entertainment announced its first franchise, the DC Super Hero Girls universe, in April 2015 with multi-platform content, toys and apparel to start appearing in 2016.[106]

Warner Bros. Pictures reorganized in May 2016 to have genre responsible film executives, thus DC Entertainment franchise films under Warner Bros. were placed under a newly created division, DC Films, created under Warner Bros. executive vice president Jon Berg and DC chief content officer Geoff Johns. This was done in the same vein as Marvel Studios in unifying DC-related filmmaking under a single vision and clarifying the greenlighting process. Johns also kept his existing role at DC Comics.[107] Johns was promoted to DC president & CCO with the addition of his DC Films while still reporting to DCE President Nelson.[108] In August 2016, Amit Desai was promoted from senior vice president, marketing & global franchise management to exec vice president, business and marketing strategy, direct-to-consumer and global franchise management.[109]

DC Entertainment and Warner Bros. Digital Networks announced in April 2017 DC Universe digital service to be launched in 2018 with two original series.[110][111]

With frustration over DC Films not matching Marvel Studios' results and Berg wanting to step back to being a producer in January 2018, it was announced that Warner Bros. executive Walter Hamada was appointed president of DC film production.[112] After a leave of absence starting in March 2018, Diane Nelson resigned as president of DC Entertainment. The company's executive management were to report to WB Chief Digital Officer Thomas Gewecke until a new president is selected.[113] In June 2018, Johns was also moved out of his position as chief creative officer and DC Entertainment president for a writing and producing deal with the DC and WB companies. Jim Lee added DC Entertainment chief creative officer title to his DC co-publisher post.[114] In September 2018, DC became part of the newly-founded Warner Bros. Global Brands and Franchises division overseen by President Pam Lifford.[115][116]

In August 2020, DC Comics publisher Jim Lee revealed that all original programming would be migrated over to HBO Max. Speaking to the community aspect of DC Universe, as well as the ability to access the backlog of comics titles, Lee said "there is always going to be a need for that" and that DC was looking at ways to transform the platform so that content would not go away.[117]

In September 2020, DC announced that the service would change its name to DC Universe Infinite and become solely a digital comics subscription service on January 21, 2021. The service would offer currently published DC Comics titles six months after their retail release date (before the change, current comics would arrive a year after their release date), early access to DC Comics' digital first titles, would feature exclusive comics created for the service, and access to 24,000 titles in DC's back catalog. DC Universe subscriptions will automatically transfer over to DC Universe Infinite.[118] Regarding the original programming, Young Justice seasons 1-4, Titans season 1-3, Doom Patrol seasons 1-3, the first season of Stargirl, and Harley Quinn seasons 1-3 will move to HBO Max to become Max Original series, with new DC series and "key DC classics" also being available on HBO Max.[119]

Logo[]

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (December 2019) |

DC's first logo appeared on the April 1940 issues of its titles. The small logo, with no background, read simply, "A DC Publication".[citation needed]

The November 1941 DC titles introduced an updated logo. This version was almost twice the size of the previous one and was the first version with a white background. The name "Superman" was added to "A DC Publication", effectively acknowledging both Superman and Batman. This logo was the first to occupy the top-left corner of the cover, where the logo has usually resided since. The company now referred to itself in its advertising as "Superman-DC".[120]

In November 1949, the logo was modified to incorporate the company's formal name, National Comics Publications. This logo also served as the round body of Johnny DC, DC's mascot in the 1960s.[citation needed]

In October 1970, DC briefly retired the circular logo in favour of a simple "DC" in a rectangle with the name of the title, or the star of the book; the logo on many issues of Action Comics, for example, read "DC Superman". An image of the lead character either appeared above or below the rectangle. For books that did not have a single star, such as anthologies like House of Mystery or team series such as Justice League of America, the title and "DC" appeared in a stylized logo, such as a bat for "House of Mystery". This use of characters as logos helped to establish the likenesses as trademarks, and was similar to Marvel's contemporaneous use of characters as part of its cover branding.[citation needed]

DC's "100 Page Super-Spectacular" titles and later 100-page and "Giant" issues published from 1972 to 1974 featured a logo exclusive to these editions: the letters "DC" in a simple sans-serif typeface within a circle. A variant had the letters in a square.[citation needed]

The July 1972 DC titles featured a new circular logo. The letters "DC" were rendered in a block-like typeface that remained through later logo revisions until 2005. The title of the book usually appeared inside the circle, either above or below the letters.[citation needed]

In December 1973, this logo was modified with the addition of the words "The Line of DC Super-Stars" and the star motif that continued in later logos. This logo was placed in the top center of the cover from August 1975 to October 1976.[citation needed]

When Jenette Kahn became DC's publisher in late 1976, she commissioned graphic designer Milton Glaser to design a new logo. Popularly referred to as the "DC bullet", this logo premiered on the February 1977 titles. Although it varied in size and colour and was at times cropped by the edges of the cover, or briefly rotated 4 degrees, it remained essentially unchanged for nearly three decades. Despite logo changes since 2005, the old "DC bullet" continues to be used only on the DC Archive Editions series.[citation needed]

In July 1987, DC released variant editions of Justice League No. 3 and The Fury of Firestorm No. 61 with a new DC logo. It featured a picture of Superman in a circle surrounded by the words "SUPERMAN COMICS". The company released these variants to newsstands in certain markets as a marketing test.[121]

On May 8, 2005, a new logo (dubbed the "DC spin") was unveiled, debuting on DC titles in June 2005 with DC Special: The Return of Donna Troy No. 1 and the rest of the titles the following week. In addition to comics, it was designed for DC properties in other media, which was used for movies since Batman Begins, with Superman Returns showing the logo's normal variant, and the TV series Smallville, the animated series Justice League Unlimited and others, as well as for collectibles and other merchandise. The logo was designed by Josh Beatman of Brainchild Studios[122] and DC executive Richard Bruning.[123]

In March 2012, DC unveiled a new logo consisting of the letter "D" flipping back to reveal the letter "C" and "DC ENTERTAINMENT".[124] The Dark Knight Rises was the first film to use the new logo, while the TV series Arrow was the first series to feature the new logo.

DC Entertainment announced a new identity and logo for another iconic DC Comics universe brand on May 17, 2016. The new logo was first used on May 25, 2016, in conjunction with the release of DC Universe: Rebirth Special #1 by Geoff Johns.[125]

Imprints[]

Active as of 2021[]

- DC (1937–present)

- Young Animal (2016–present)

- WildStorm (1999–2010, 2017–present)

- Earth-M (1993–1997, 2018–present)

- DC Black Label (2018–present)[126]

- Sandman Universe (2018–present)

- Hill House Comics (2019–present)

- Wonder Comics (2019–present)

- DC Graphic Novels for Young Adults (2020–present)

- DC Graphic Novels for Kids (2020–present)

- Mad (1953–present)

Defunct[]

- DC Archive Editions (1989–2014; replaced by DC Omnibus)

- Elseworlds (1989–2004)

- Piranha Press (1989–1993; renamed Paradox Press)

- Impact Comics (1991–1993; licensed from Archie Comics)

- Vertigo (1993–2019)[5]

- Amalgam Comics (1996–1997; jointly with Marvel Comics)

- Helix (1996–1998; merged with Vertigo)

- Tangent Comics (1997–1998)

- Paradox Press (1998–2003)

- WildStorm Productions (1999–2010)

- America's Best Comics (1999–2005)

- Homage Comics (1999–2004; merged to form WildStorm Signature)

- Cliffhanger (1999–2004; merged to form WildStorm Signature)

- WildStorm Signature (2004–2006; merged with main WildStorm line)

- CMX Manga (2004–2010)

- DC Focus (2004–2005; merged with main DC line)

- Johnny DC (2004–2012)

- All Star (2005–2008)

- Minx (2007–2008)

- Zuda Comics (2007–2010)

- First Wave (2010–2011; licensed from Condé Nast Publications and Will Eisner Library)

- DC Ink (2019–2019; replaced by DC Graphic Novels for Young Adults)

- DC Zoom (2019–2019; replaced by DC Graphic Novels for Kids)

DC Universe Infinite[]

DC Universe was a video on demand service operated by DC Entertainment. It was announced in April 2017,[127] with the title and service formally announced in May 2018. DC Universe offered video content, fan interaction, comics, and television.[111][128][129][130] In August 2020, DC publisher Jim Lee announced that all video content from DC Universe would migrate to HBO Max,[131] with the majority of the staff of DC Universe having been laid off.[132]

In January 2021, the service relaunched as DC Universe Infinite, a completely comic-centric platform, comparable to Marvel Unlimited, offering DC's entire back catalog of comics, as well as new titles sixth months after their on-sale date.[133]

Films[]

| Year | Film | Directed by | Written by | Based on | Production by | Budget | Gross | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Batman Begins | Christopher Nolan | Story by David S. Goyer Screenplay by Christopher Nolan and David S. Goyer |

Batman by Bob Kane with Bill Finger |

Warner Bros. / Legendary Pictures / Patalex III Productions / Syncopy | $150 million | $374.2 million | |

| 2006 | Superman Returns | Bryan Singer | Story by Bryan Singer, Michael Dougherty and Dan Harris Screenplay by Michael Dougherty and Dan Harris |

Superman by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster |

Warner Bros. / Legendary Pictures / Bad Hat Harry Productions / Peters Entertainment | $204 million | $391.1 million | |

| 2008 | The Dark Knight | Christopher Nolan | Story by Christopher Nolan and David S. Goyer Screenplay by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan |

Batman by Bob Kane with Bill Finger |

Warner Bros. / Legendary Pictures / Syncopy | $185 million | $1.005 billion | |

| 2009 | Watchmen | Zack Snyder | David Hayter and Alex Tse | Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons |

Warner Bros. / Paramount Pictures / Legendary Pictures / Lawrence Gordon Productions | $130 million | $185.3 million | |

| 2010 | Jonah Hex | Jimmy Hayward | Story by Neveldine/Taylor and William Farmer Screenplay by Neveldine/Taylor |

Jonah Hex by John Albano and Tony DeZuniga |

Warner Bros. / Legendary Pictures / Weed Road Pictures | $47 million | $10.9 million | |

| 2011 | Green Lantern | Martin Campbell | Story by Greg Berlanti, Michael Green and Marc Guggenheim Screenplay by Greg Berlanti, Michael Green, Marc Guggenheim and Michael Goldenberg |

Green Lantern by John Broome and Gil Kane |

Warner Bros. / De Line Pictures | $200 million | $219.9 million | |

| 2012 | The Dark Knight Rises | Christopher Nolan | Story by Christopher Nolan and David S. Goyer Screenplay by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan |

Batman by Bob Kane with Bill Finger |

Warner Bros. / Legendary Pictures / Syncopy | $230 million | $1.085 billion | |

| 2013 | Man of Steel | Zack Snyder | Story by Christopher Nolan and David S. Goyer Screenplay by David S. Goyer |

Superman by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster |

Warner Bros. / Legendary Pictures / Syncopy | $225 million | $668 million | |

| 2016 | Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice | Zack Snyder | Chris Terrio and David S. Goyer | Batman by Bob Kane with Bill Finger Superman by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster |

Warner Bros. / RatPac Entertainment / Atlas Entertainment / Cruel and Unusual Films | $250 million | $873.6 million | |

| Suicide Squad | David Ayer | Suicide Squad by John Ostrander |

Warner Bros. / DC Films / RatPac Entertainment / Atlas Entertainment | $175 million | $746.8 million[134] | |||

| 2017 | The Lego Batman Movie | Chris McKay | Story by Seth Grahame-Smith Screenplay by Seth Grahame-Smith, Chris McKenna & Erik Sommers, Jared Stern & John Whittington |

Batman by Bob Kane with Bill Finger |

Warner Bros. / LEGO System A/S / Warner Animation Group / RatPac Entertainment / Lin Pictures / Lord Miller Productions / Vertigo Entertainment | $80 million[135] | $310.7 million[135] | |

| Wonder Woman | Patty Jenkins | Story by Zack Snyder & Allan Heinberg and Jason Fuchs Screenplay by Allan Heinberg |

Wonder Woman by William Moulton Marston |

Warner Bros. / DC Films / RatPac Entertainment / Atlas Entertainment / Cruel and Unusual Films | $150 million[136] | $821.8 million[136] | ||

| Justice League | Zack Snyder | Story by Chris Terrio & Zack Snyder Screenplay by Chris Terrio and Joss Whedon |

Justice League by Gardner Fox |

Warner Bros. / DC Films / RatPac Entertainment / Atlas Entertainment / Cruel and Unusual Films | $300 million | $657.9 million[137] | ||

| 2018 | Teen Titans Go! To the Movies | Aaron Horvath & Peter Rida Michail | Screenplay by Aaron Horvath & Michael Jelenic | Teen Titans by Bob Haney and Bruno Premiani Teen Titans Go! by Aaron Horvath and Michael Jelenic |

Warner Bros. / Warner Bros. Animation[138] | $10 million[139] | $51.9 million[139] | |

| Aquaman | James Wan | Story by James Wan and Geoff Johns Screenplay by Will Beall |

Aquaman by Mort Weisinger and Paul Norris | Warner Bros. / DC Films / Cruel & Unusual Films[140] | $160 million[141] | $1.148 billion[142] | ||

| 2019 | Shazam! | David F. Sandberg | Story by Henry Gayden and Darren Lemke Screenplay by Henry Gayden |

Shazam! by Bill Parker and C. C. Beck | New Line Cinema / DC Entertainment[140] | $80–100 million[143][144] | $365.9 million[145] | |

| Joker | Todd Phillips | Todd Phillips and Scott Silver | Joker by Bill Finger, Bob Kane and Jerry Robinson | Warner Bros. Pictures / Bron Creative / Village Roadshow Pictures / Joint Effort / DC Films[140] | $55–70 million[146] | $1.074 billion[147] | ||

| 2020 | Birds of Prey | Cathy Yan | Christina Hodson | Birds of Prey by Jordan B. Gorfinkel and Chuck Dixon | Warner Bros. Pictures / DC Films / LuckyChap Entertainment / Kroll & Co. Entertainment / Clubhouse Pictures | $82–100 million[148] | $201.9 million[149] | |

| Wonder Woman 1984 | Patty Jenkins | Story by Patty Jenkins and Geoff Johns Screenplay by Patty Jenkins, Geoff Johns and David Callaham |

Wonder Woman by William Moulton Marston |

Warner Bros. Pictures / The Stone Quarry / DC Films / Atlas Entertainment[140] | $200 million[150] | $159.5 million[151] | ||

| 2021 | Zack Snyder's Justice League | Zack Snyder | Story by Chris Terrio & Zack Snyder and Will Beall

Screenplay by Chris Terrio |

Justice League by Gardner Fox | Warner Bros. Pictures / DC Films / The Stone Quarry / Atlas Entertainment | $70 million[152] | Released as an HBO Max exclusive | |

| Upcoming films | Status | |||||||

| 2021 | The Suicide Squad | James Gunn | Suicide Squad by John Ostrander |

Warner Bros. Pictures / DC Films / Atlas Entertainment / The Safran Company | Post-production | |||

| 2022 | The Batman | Matt Reeves | Matt Reeves & Peter Craig | Batman by Bob Kane with Bill Finger |

Warner Bros. Pictures / DC Films / 6th & Idaho Productions | Post-production | ||

| DC League of Super-Pets | Jared Stern | Legion of Super-Pets by Bob Kane with Bill Finger |

Warner Bros. Pictures / Warner Anination Group / DC Films / Seven Bucks Productions / A Stern Talking To | |||||

| Black Adam | Jaume Collet-Serra | Adam Sztykiel, Rory Haines & Sohrab Noshirvani | Black Adam by Otto Binder and C. C. Beck |

Warner Bros. Pictures / DC Films / New Line Cinema / Seven Bucks Productions / FlynnPictureCo. | Filming | |||

Critical and public reception[]

| Film | Rotten Tomatoes | Metacritic | CinemaScore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batman Begins | 84% (278 reviews)[153] | 70 (41 reviews)[154] | A |

| Superman Returns | 75% (263 reviews)[155] | 72 (40 reviews)[156] | B+ |

| The Dark Knight | 94% (334 reviews)[157] | 82 (39 reviews)[158] | A |

| Watchmen | 64% (305 reviews)[159] | 56 (39 reviews)[160] | B |

| Jonah Hex | 12% (149 reviews)[161] | 33 (32 reviews)[162] | C+ |

| Green Lantern | 26% (239 reviews)[163] | 39 (39 reviews)[164] | B |

| The Dark Knight Rises | 87% (358 reviews)[165] | 78 (45 reviews)[166] | A |

| Man of Steel | 56% (329 reviews)[167] | 55 (47 reviews)[168] | A− |

| Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice | 28% (411 reviews)[169] | 44 (51 reviews)[170] | B |

| Suicide Squad | 27% (362 reviews)[171] | 40 (53 reviews)[172] | B+ |

| The Lego Batman Movie | 90% (301 reviews)[173] | 75 (48 reviews)[174] | A− |

| Wonder Woman | 93% (433 reviews)[175] | 76 (36 reviews)[176] | A |

| Justice League | 40% (377 reviews)[177] | 45 (52 reviews)[178] | B+ |

| Teen Titans Go! To the Movies | 91% (121 reviews)[179] | 69 (25 reviews)[180] | B+ |

| Aquaman | 66% (374 reviews)[181] | 55 (49 critics)[182] | A− |

| Shazam! | 91% (378 reviews)[183] | 71 (52 critics)[184] | A |

| Joker | 69% (524 reviews)[185] | 59 (58 reviews)[186] | B+ |

| Birds of Prey | 79% (342 reviews)[187] | 60 (59 reviews)[188] | B+ |

| Wonder Woman 1984 | 60% (398 reviews)[189] | 60 (57 reviews) [190] | B+ |

| Average | 67% | 57 | B+ |

Digital distribution[]

DC Comics are available in digital form through several sources.

Free services: In 2015, Hoopla Digital became the first library-based digital system to distribute DC Comics.[191]

Paid services: Google Play, ComiXology[192]

See also[]

- Batman Day (September 17)

- DC Cosmic Cards

- DC Collectibles

- List of DC Comics characters

- List of comics characters which originated in other media

- List of current DC Comics publications

- List of films based on DC Comics publications

- List of television series based on DC Comics publications

- List of video games based on DC Comics

- Publication history of DC Comics crossover events

- List of unproduced DC Comics projects

- DC Films

Notes[]

- ^ In a 1947–1948 lawsuit field by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster against National, the presiding judge noted in a "Findings of Facts": "DETECTIVE COMICS, INC. was a corporation duly organized and existing under the laws of the State of New York, and was one of the constituent corporations consolidated on September 30, 1946 into defendant NATIONAL COMICS PUBLICATIONS, INC."[42]

- ^ Apocryphal legend has it that in 1961, either Jack Liebowitz or Irwin Donenfeld of DC Comics (then known as National Periodical Publications) bragged about DC's success with the Justice League (which had debuted in The Brave and the Bold No. 28 [February 1960] before going on to its own title) to publisher Martin Goodman (whose holdings included the nascent Marvel Comics, which was being distributed by DC's Independent News at this time.) during a game of golf.

However, film producer and comics historian Michael Uslan partly debunked the story in a letter published in Alter Ego No. 43 (December 2004), pp. 43–44Irwin said he never played golf with Goodman, so the story is untrue. I heard this story more than a couple of times while sitting in the lunchroom at DC's 909 Third Avenue and 75 Rockefeller Plaza office as Sol Harrison and [production chief] Jack Adler were schmoozing with some of us ... who worked for DC during our college summers ... [T]he way I heard the story from Sol was that Goodman was playing with one of the heads of Independent News, not DC Comics (though DC owned Independent News) ... As the distributor of DC Comics, this man certainly knew all the sales figures and was in the best position to tell this tidbit to Goodman. ... Of course, Goodman would want to be playing golf with this fellow and be in his good graces ... Sol worked closely with Independent News' top management over the decades and would have gotten this story straight from the horse's mouth.

Goodman, a publishing trend-follower aware of the JLA's strong sales, confirmably directed his comics editor, Stan Lee, to create a comic-book series about a team of superheroes. According to Lee: "Martin mentioned that he had noticed one of the titles published by National Comics seemed to be selling better than most. It was a book called The [sic] Justice League of America and it was composed of a team of superheroes. ... ' If the Justice League is selling ', spoke he, 'why don't we put out a comic book that features a team of superheroes?'"[47]

Citations[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marx, Barry, Cavalieri, Joey and Hill, Thomas (w), Petruccio, Steven (a), Marx, Barry (ed). "Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson DC Founded" Fifty Who Made DC Great: 5 (1985), DC Comics

- ^ Jump up to: a b McMillan, Graeme (June 5, 2020). "DC Cut Ties with Diamond Comic Distributors". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McMillan, Graeme (January 23, 2019). "DC Publishing Laying Off 3 Percent of Its Workforce". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- ^ Melrose, Kevin (October 10, 2009). "DC Entertainment – what we know so far". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on September 13, 2009. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "DC Entertainment Expands Editorial Leadership Team" (Press release). DC Entertainment. May 5, 2017. Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b DC Comics Inc. Archived September 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Hoovers. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ^ "DC Comics, Random House Ink Distribution Pact". Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ "Welcome to Diamond Comic Distributors' Retailer Services Website!". Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ Miller, John. "2017 Comic Book Sales to Comics Shops". Comichron. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

Share of Overall Units—Marvel 38.30%, DC 33.93%; Share of Overall Dollars—Marvel 36.36%, DC 30.07%

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Fifty Who Made DC Great

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The 100 Most Influential Pages in Comic Book History". Vulture. April 16, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ Goulart, Ron (1986). Ron Goulart's Great History of Comics Books. Contemporary Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-8092-5045-4.

- ^ Benton, Mike (1989). The Comic Book in America: An Illustrated History. Dallas, Texas: Taylor Publishing. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-87833-659-3.

- ^ New Fun #1 (Feb. 1935) at the Grand Comics Database. The entry notes that while the logo appears to be simply Fun, the indicia reads, "New FUN is published monthly at 49 West 45th Street, New York, N.Y., by National Allied Publications, Inc.; Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, President ... Inquiries concerning advertising should be addressed to the Advertising Manager, New FUN,...."

- ^ Wolk, Douglas (July 5, 2010). "75 Years of the First Comic Book Superhero (It's Not Who You Think)". Time. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilson, John (December 16, 2019). "10 Things Everyone Forgets About DC's Dr. Occult". CBR. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ New Comics Archived December 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Jones 2004, p. 125.

- ^ Jones 2004, p. [page needed].

- ^ "Superman's debut sells for $1M at auction". Crain's New York Business. Associated Press. February 22, 2010. Archived from the original on March 11, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wallace, Daniel; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "1930s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Cronin, Brian (January 20, 2018). "Who Was the First Comic Book Masked Vigilante?". CBR. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ Hall, Richard A. (2019). The American Superhero: Encyclopedia of Caped Crusaders in History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440861246.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wallace, Daniel (2013). Superman: The Ultimate Guide to the Man of Steel. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 126. ISBN 978-1465408754.

- ^ "Jimmy Olsen". dcuniverse.com. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ "Superman: The Golden Age Sundays 1943–1946". The Comics Journal. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Daniels, Les (April 2004). Batman – The Complete History: The Life and Times of the Dark Knight. ISBN 978-0-8118-4232-7.

- ^ "Don Markstein's Toonopedia: The Red Tornado". toonopedia.com. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ Benton, Mike (1992). Superhero Comics of the Golden Age: The Illustrated History. Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company. pp. 123-124. ISBN 0-87833-808-X. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ Das, Manjima (February 17, 2020). "Batman And Superman : The Two Superheroes Are Going To Fight The First DC Villain". Trending News Buzz. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ Wallace, Daniel; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "1930s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.

Superman's runaway popularity as part of Action Comics earned him his own comic. This was a real breakthrough for the time, as characters introduced in comic books had never before been so successful as to warrant their own titles.

CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) - ^ White, Chris (November 23, 2019). "DC: The 10 Rarest Batman Comics (& What They're Worth)". CBR. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ Irving, Christopher (2007). The Blue Beetle Companion: His Many Lives from 1939 to Today. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781893905702. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Hall, Richard A. (2019). The American Superhero: Encyclopedia of Caped Crusaders in History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440861246. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme. "A Guide to the Fictional Cities of the DC Universe". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ Webber, Tim (September 19, 2017). "The Metropo-list: 15 DARK Secrets You NEVER Knew About Superman's City". CBR. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ^ "15 Best Comic Book Origin Stories Of All Time". ScreenRant. March 15, 2017.

- ^ Siegel, Jerry; Ellsworth, Whitney (February 7, 2017). Superman : the Golden age dailies 1942–1944. ISBN 978-1-63140-383-5.

- ^ Kooiman, Mike; Amash, Jim (November 2011). Quality Companion, The. Raleigh, NC: TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-60549-037-3.

- ^ "An Oral History of DC's CAPTAIN MARVEL/SHAZAM: The Fawcett Years, Part 1". Newsarama. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ "Young April 12, 1948 Findings of Facts" – via SCRIBD.

- ^ Jones 2004, p. 223.

- ^ "'Superman Faces New Hurdles: Publishers of Comic Books Showing Decline". The New York Times. September 23, 1962. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

It was just a year ago that some rather surprising news was announced to the world about a venerable American institution. The announcement said that Superman had gone public.

- ^ Maggie Thompson, Michael Dean, Brent Frankenhoff, Joyce Greenholdt, John Jackson Miller (editors), Comics Buyer's Guide 1996 Annual, Krause Publications, 1995, p. 81: "Beginning as National Allied Publications in 1935 [sic] and becoming National Allied Newspaper Syndicate the next year, it changed to National Comic [sic] Publications in 1946 and National Periodical Publications in 1961"

- ^ DC Comics, Inc. Archived May 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine at Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- ^ Origins of Marvel Comics (Simon and Schuster/Fireside Books, 1974), p. 16

- ^ Integrative Arts 10: "The Silver Age" by Jamie Coville Archived June 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ Tucker 2017, p. xiii.

- ^ Tucker 2017, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Tucker 2017, p. 28.

- ^ Eury, Michael (July 2013). "The Doom Patrol Interviews: Editor's Note". Back Issue!. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (65): 37.

- ^ Epstein, Daniel Robert (November 11, 2005). "Talking to Arnold Drake". Newsarama. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ Irving, Christopher (July 20, 2012). "Jim Shooter's Secret Origin, in his Own Words – Part One" Archived August 20, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Graphic NYC.

- ^ Evanier, Mark (December 1, 2004). "Irwin Donenfeld, R.I.P." Archived from the original on May 18, 2008. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ Tucker 2017, p. 34.

- ^ "DC Comics". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. November 17, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Gaiman, Mark Evanier; introduction by Neil (2008). Kirby : King of Comics. New York City: Abrams. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-8109-9447-8.

- ^ "DC Comics, Inc.: Private Company Information". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2016-08-06.

- ^ Eury, Michael (December 2002). Captain Action: The Original Super-Hero Action Figure. TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 1893905179. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ Tucker 2017, p. 110.

- ^ Kahn, Jenette. "Publishorial: Onward and Upward" Archived March 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, DC Comics cover-dated September 1978.

- ^ "The DC Implosion", The Comics Journal No. 41 (August 1978), pp. 5–7.

- ^ "Post-Implosion Fill-In Fallout", The Comics Journal No. 43 (December 1978), p. 13.

- ^ Steranko, Jim (February 1975). "Mediascene" (11). p. ?.

Atlas/Seaboard publisher Martin Goodman's David and Goliath strategy is insidiously simple and outrageous—possibly even considered dirty tactics by the competition—[and consists of] such [things] as higher page rates, artwork returned to the artist, rights to the creation of an original character, and a certain amount of professional courtesy.

- ^ Tucker 2017, pp. 112–113.

- ^ "GHM Columns : GHM Staff : Steve Higgins A+ Graphic Novels ]". Newcomicreviews.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ^ MacDonald, Heidi D. "DC's Titanic Success", The Comics Journal No. 76 (October 1982), pp. 46–51.

- ^ "Why TEEN TITANS Is DC Comics' Most Important (But Undervalued) Franchise – Nerdist". August 30, 2016. Archived from the original on November 18, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ "Vertigo (Publisher) – Comic Vine". Comic Vine. Archived from the original on July 15, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ "Batman's Dark Side". March 26, 2016. Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ "How the Year 1986 Changed Comic Books Forever". Nerdist. Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- ^ Arrant, Chris (April 29, 2009). "Completing the Red Circle: Talking to JMS". Newsarama. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Markstein, Don. "Archie (MLJ) Comics". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "JMS Circles the DC Universe in Red" Archived October 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Comic Book Resources. March 26, 2009

- ^ Brady, Matt (August 21, 2006). "Adam Hughes on His New Exclusive & All Star Wonder Woman". Newsarama.com. Archived from the original on August 30, 2006.

- ^ Renaud, Jeffrey (October 30, 2008). "JMS Gets Brave & Bold with Archie Gang". ComicBookResources.com. Archived from the original on July 6, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ "20 Answers and 1 Question With Dan DiDio: Holiday Surprise". Newsarama.com. December 24, 2008. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ Rogers, Vaneta (March 3, 2010). "Brian Azzarello Gets Ready to Break DC's First Wave". Newsarama. Archived from the original on April 7, 2010. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (February 23, 2011). "First Wave Crashes – DC To Cancel Line". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ Bondurant, Tom (May 19, 2011). "Grumpy Old Fan Growing the garden: DC's May solicits". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ Hyde, David (May 31, 2011). "DC Comics Announces Historic Renumber of All Superhero Titles and Landmark Day-and-Date Digital Distribution". DC Entertainment. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ^ Truitt, Brian (May 31, 2011). "DC Comics unleashes a new universe of superhero titles". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- ^ Richards, Ron (June 6, 2011). "The Definitive Guide to the DC Comics Reboot". iFanboy.com. Archived from the original on June 19, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- ^ "DC Entertainment Brings Digital Comics to the Net Level With New DC2 and DC2 Multiverse Innovations" (Press release). DC Entertainment. June 4, 2013. Archived from the original on June 8, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ "DC's Band-Aid Event? It's Not Blood Moon. It's Called Convergence". Bleeding Cool. October 28, 2014. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- ^ "New villain, old tales part of DC's 'Convergence'". USA Today. November 3, 2014. Archived from the original on July 22, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ Beedle, Tim (November 6, 2014). "FIRST LOOK: The Complete Convergence". DC Entertainment. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- ^ "DC's CONVERGENCE Week One: Donna Troy, Oracle, Married Superman, Montoya Question, More". Newsarama.com. November 11, 2014. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- ^ "DC ENTERTAINMENT REVEALS FIRST DETAILS OF "REBIRTH" TO RETAILERS AT COMICS PRO 2016" (Press release). DC Entertainment. February 18, 2016. Archived from the original on April 12, 2018. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (September 2016). "DC Comics' 'Rebirth' brings new life – and huge sales – to old superheroes". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 12, 2018. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "How DC Comics Scored Its Biggest Win in Years With 'Rebirth'". Archived from the original on April 12, 2018. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "DC Comics' Rebirth worked because it's actually good". Archived from the original on April 12, 2018. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Faughnder, Ryan (February 21, 2020). "DC Entertainment shakeup continues with the exit of co-publisher Dan DiDio". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (February 21, 2020). "Dan DiDio No Longer Publisher of DC Comics, As Of Today". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (February 21, 2020). "So Why Did Dan DiDio Leave DC Comics Anyway?". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "DC FanDome: Warner Bros. Announces 'Immersive Virtual Fan Experience' as Comic-Con-Style Event". IGN. August 19, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- ^ "DC FanDome splits into 2 days: Get the details". ew.com. August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Agard, Chancellor (December 11, 2020). "DC FanDome to return with Wonder Woman 1984 virtual premiere, sneak peek". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- ^ "DC FanDome is Returning in 2021!". DC. April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ "DC Comics, DC Universe Hit By Major Layoffs". Hollywood Reporter. August 10, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ "'Infinite Frontier' Launches Next Era of the DC Universe". Hollywood Reporter. March 26, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Warner Bros. Creates DC ENTERTAINMENT To Maximize DC Brands". Newsarama. Archived from the original on September 11, 2009. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ "DC Names DiDio & Lee Co-Publisher, Johns Chief Creative Officer". Comic Book Resources. February 18, 2010. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "Warner's DC comic-book unit leaving Gotham". The San Diego Union-Tribune. October 29, 2013. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ Prudom, Laura (April 23, 2015). "DC Launches 'Super Hero Girls' Universe to Appeal to Young Female Comics Fans". Variety. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ "'Batman v. Superman' Fallout: Warner Bros. Shakes Up Executive Roles". The Hollywood Reporter. May 17, 2016. Archived from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (July 27, 2016). "Geoff Johns Confirmed as DC Entertainment President". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ Kit, Borys (August 12, 2016). "DC Entertainment Promotes Amit Desai to Chief of Business and Marketing Strategy". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (April 25, 2017). "DC Digital Service To Launch With 'Titans' Series From Greg Berlanti & Akiva Goldsman And 'Young Justice: Outsiders'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Petski, Denise (May 2, 2018). "DC's New Digital Service Gets A Name". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2018.